by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta , published on 13/10/2017

Categories: Works and artists

- Quaderni di viaggio / Disclaimer

Villa Durazzo-Pallavicini in Genoa houses a wonderful park, which the patron conceived so that visitors could take an initiatory journey within it.

There is a heavy gate ahead. If you go through it, we can imagine that there is no turning back. Two columns flank the entrance, and above them two statues depicting two fierce dogs on guard are almost meant to admonish the visitor who enters this park, where an initiatory journey will take place:a journey that will take us around the world, take us back through ancient history, bring us down to the underworld and elevate us to the heights of knowledge and bliss.

We are in Genoa, in the district of Pegli, and exactly in the park of Villa Durazzo-Pallavicini. The villa is a sober neoclassical building, the result of the remodeling of an earlier 18th-century palace that belonged to Giovanni Battista Grimaldi, doge of the Republic of Genoa between 1752 and 1754: today the building is home to the Museum of Ligurian Archaeology. But what has been moving anyone passing through the place for centuries in wonderment is not so much the villa as the large park that opens up behind the former residence of the Durazzo and Pallavicini families. Its history begins with the botanical garden opened, in 1794, by the marquise Clelia Durazzo (Genoa, 1760 - Pegli, 1837), wife of a member of the Grimaldi family, Giuseppe, and a botanical scholar: the noblewoman used to make frequent trips abroad, from which she returned each time with plant species, some of them very rare, in order to enrich the garden of the villa in Pegli. And perhaps it was precisely this passion for botany that was one of the reasons that prompted one of her nephews, Marquis Ignazio Alessandro Pallavicini (Milan, 1800 - Genoa, 1871), to add to theHorto Grimaldiano cared for by his aunt, extensively rearranged for the occasion (and still in existence today), a large romantic park that has no equal in Italy and represents a point of excellence even at the European level.

|

| The main facade of Villa Durazzo-Pallavicini. Ph. Credit |

Ignazio Pallavicini did not only intend to enrich the villa with a park in which to spend pleasant moments: he wanted it to reflect his way of conceiving the world, his philosophical reflections, his cultural experiences, and his historical and literary knowledge. And he aspired to share this journey among philosophical, literary, mythological, botanical and esoteric suggestions with anyone who visited it, so much so that the project even included conducting guided tours for guests. So in 1840 he turned to one of the leading stage designers of the time, architect Michele Canzio (Genoa, 1787 - Castelletto Monferrato, 1868), to whom he entrusted the project, which was completed in 1846. Times had changed: Clelia Durazzo’s scientific rigor was being replaced by Ignazio Pallavicini’s fantasies, contemplations, wanderings and fantastic imagination.

The marquis was a theater enthusiast, and he wanted to imagine his park as a large and long theatrical drama, which the visitor would walk through from the prologue to the exodus, through three acts corresponding to the three different "sections" of the park, each divided into four scenes. The visitor then finds himself traveling through a world consisting of sumptuous gardens, intricate forests, exotic settings, pagan temples, echoes of medieval history, fountains, lakes and waterfalls, and water features, all in a park that spreads, over eight hectares, on the side of a hill overlooking the sea: each step toward the goal is a constant surprise as well as an achievement toward the next step, for the path in the park is imagined almost as a gradual advance toward the final rebirth in the sign of love, brotherhood and light, understood in the Masonic sense of enlightenment, knowledge of self and the world, truth, distinction. In fact, Ignazio Pallavicini belonged to Freemasonry, and the park is configured, explain scholars Silvana Ghigino (who of Villa Durazzo-Pallavicini is currently director) and Fabio Calvi, as a path faithful to the Masonic motto "If you have the strength to persevere, you will come out purified and see the Light," so much so that it has become "a place that responds in every way to this coveted achievement." The visitor is called to a continuous work of refinement, which will pass through the abandonment of materiality, death, purification of the soul and arrive at the attainment of the Light. But the intentions that animated the bizarre patron, perhaps, went further: membership in Freemasonry, explains scholar Francesca Mazzino, was also a bond that strengthened power groups, which at the time "attributed to themselves the task of launching society toward progress and modernity." The journey’s path was thus also understood as a journey of education.

This journey, whatever the intent and whoever the traveler who takes part in it, begins, as mentioned in the opening, from the gate of the park, watched on sight by the two dogs, sculpted by Giovanni Battista Cevasco (Genoa, 1817 - 1891) and placed up there in 1845: it is they who stand guard and instill in us the sense of uneasiness that increases as we pass through the Gothic avenue, a narrow street initially flanked by a medieval building (the Gothic tribune), which then unravels through a dark thicket and constitutes the prologue to the theatrical drama we are about to experience as absolute protagonists. What the Gothic Avenue intends to convey to us is the sense of bewilderment that characterizes our lives, similar to that experienced by Dante Alighieri in the dark forest that opens his Comedy, and which creates upheavals to our spirits. Soon, however, the scenery changes completely. We catch a glimpse of a neoclassical building: it is the Coffee House, through which we pass from the gloom of the Gothic avenue to the full sunlight and harmony of the Classical avenue. We are in a wonderful Italian garden pathway: on either side, pots with plants in rows, neatly arranged. In the center, a fountain. Closing the driveway, an archof triumph. We breathe a sigh of relief, for from the woods we have returned to civilization. But it is only here, in the city driveway, that we understand what our initial sense of bewilderment was due to: we are, after all, city men and women, constantly harassed by our daily worries, our empty ambitions, the barrenness of our material greed that contaminates our spirit and turns us away from the light. On the triumphal arch, an inscription represents both a warning and an invitation: Valete urbani labores / Valete procul animi impedimenta / Me supera convexa et sylvae et fonteis / Et quid quid est altiora loquentis naturae / Evehat ad Deum ("Farewell, cares of the city! Be gone, afflictions of the soul! The sky, the woods, the springs and all that is sublime in nature elevate me to God."). This concludes the prologue of the drama (and of our journey): we are thus invited to leave the city behind and descend into unspoiled nature to begin to recover our spirit.

|

| Prologue: the gate with the guard dogs and the beginning of the Gothic Avenue. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| The Gothic grandstand. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| The end of the Gothic avenue. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| The coffee house. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Prologue: the Classical avenue. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| The triumphal arch. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

Immediately after the triumphal arch, a short flight of steps leads us into a grove. From the top of the climb, we make to turn around: we want to make sure that we have really left the city and its monuments. But we have a first surprise: the triumphal arch is completely gone. In fact, Canzio’s set design has turned it into a little mountain house, made of stone, with a slate roof. This is the beginning of the first act of the drama: the return to nature. Which begins right here, from the hermitage scene. The house we have just seen is that of thehermit who has abandoned the mundane life and decided to live in the woods. To begin this journey into mysterious nature, of course, requires an act of courage, similar to that performed by the hermit who intends to show us the beginning of our journey. But it is an act of courage that rewards us, for as we continue our journey through the forest we find ourselves in abeautiful and lush unanature that makes us make aworld first: the plants we find in this area of the park come, in fact, from all corners of the earth. We find the plants of the Mediterranean maquis that evoke memories linked to our lands, the exotic palms that make us dream of tropical landscapes, the araucaria that takes us to South America, the marvelous camellias that open up scenarios on the Far East: here, in the park of Villa Durazzo-Pallavicini there is one of the oldest existing collections of camellias. Nineteenth-century specimens still bloom, and seeing them in spring is a kind of enchantment that bewitches us during our journey, but if we are lucky we may encounter some particularly robust flowers in the remaining months of the year as well. The transition to the second scene takes us to the amusement park.

Rides await us on which we can relax, in a place where we can spend carefree moments. Re-establishing a sincere contact with nature allows us to return to pure emotions and feelings, like those of a child having fun on the rides (in the Park we can find the original nineteenth-century rides, a stunning sight for the time). But our journey into nature is still far from complete. We begin to climb up the hill, and arrive at a kind of clearing, on the shores of a lake: it is the Old Lake, the third scene of the first act, and we pause for a moment in front of its murky waters, in which fish swim and over which shade the trees of the dense vegetation. It is total immersion in nature: there are no longer even poor hermit buildings, no pathways arranged by the hand of man. Here, everything is spontaneous, and we feel all the strength, energy and beauty of nature. The water is murky because to arrive at complete "mental and moral chastity" we must follow the saving action of the water itself and arrive at the fourth and final scene of Act III, the spring, which by its regenerative action makes us totally ready to depart from matter.

|

| Act I (the return to nature), Scene I: the hermitage. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| The driveway with the palm trees. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| A camellia in the middle of autumn. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Act I, Scene II: The amusement park. One of the rides. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Act I, Scene III: the Old Lake. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Act I, Scene IV: the spring. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

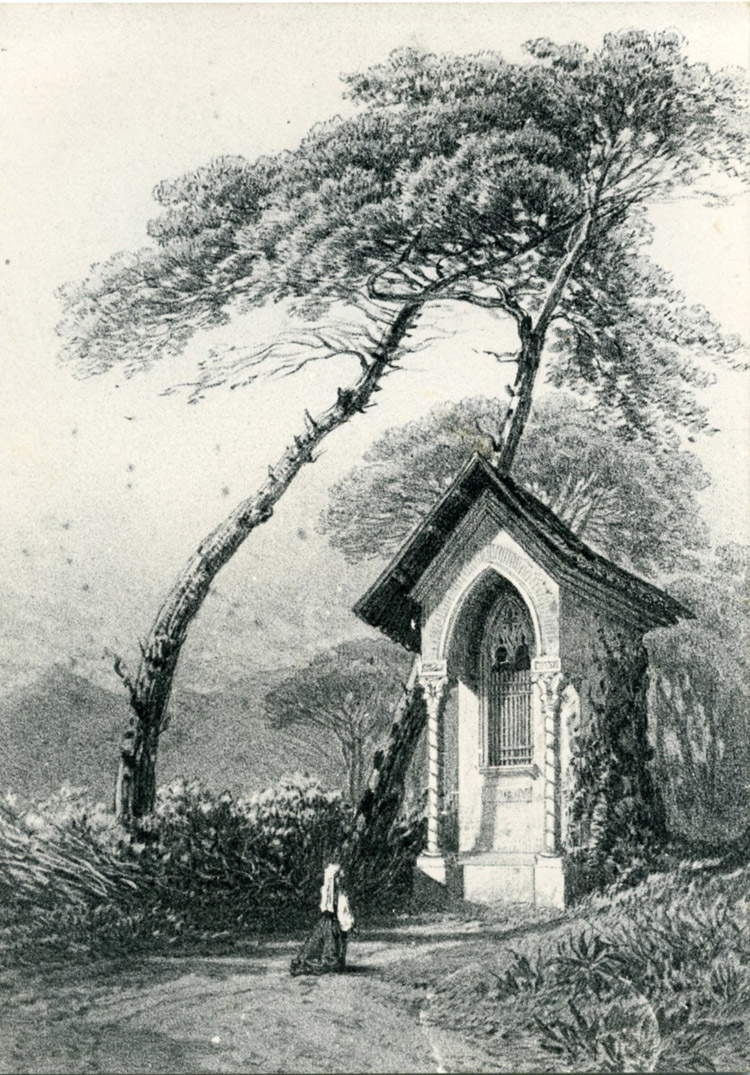

Having recovered our natural dimension throughout, it is time toreflect on the past with a renewed gaze. We make our way to the top of the hill, and begin to enjoy the view of the sea as well, imagining how amazing it must have been in Marquis Pallavicini’s time, when the view did not meet Pegli’s mansions, the airport, the industries of the port area: just a village at our feet, the beach, the sea water. At a certain point, in front of us, here are the ruins of the little chapel of Mary: it is the first scene of the second act, the recovery of history. The Gothic shrine, housing an image of the Virgin painted by Giuseppe Isola (Genoa, 1808 - 1893), lets us know that we are about to enter a medieval fiefdom, an ancient village: however, nothing remains of it but a simple hut, the so-calledSwiss hut (the second scene, currently under restoration). We begin to wonder about the fate of this lost hamlet, now shrouded only in silence. The ideas become clear when we reach the top of the hill: we stand in front of the Captain’s Castle, the third scene of the second act. From protagonists of the initiatory journey we become for a few moments spectators of a tale, the outcome of which will cause us to meditate on the fate of our existences.

Indeed, we discover that the village that no longer exists was ruled by a valiant Captain, who lived in the now ruined castle (the marquis wanted to have it built by Canzio according to the typical nineteenth-century imagery of the medieval castle: with a high tower, battlements, stained glass windows, and a drawbridge). Walking through the rooms of the castle (the third scene), we perceive how much the Captain had sought to gain glory in life and surround himself with comforts and pleasures, but also how hard he had tried to defend his castle and village against rival fiefs: going up, on the hill in front of us, we indeed saw in the distance another castle (which is nothing more than a farmhouse appropriately disguised by Canzio: the marquis wanted the interventions to affect the surrounding landscape as well), symbolizing the struggles undertaken by the Captain against his enemies. But the end came for him as well: the death we encounter in the fourth and final scene of Act II, the Captain’s mausoleum, ended the leader’s ambitions of glory and wealth and cast into oblivion his village, which time has erased from the earth. Observing the Captain’s Gothic ark, we understand the vanity of the pursuit of earthly things, and we understand what is, continuing to read in Calvi and Ghigino’s book, "the fate destined for the humanity of domination, which builds, subjugates, conquers, surrounds itself with wealth and vain glory and then sinks into the darkest and most impersonal death." Our spirit has understood and recovered the story: from being spectators of human affairs, we can once again become actors in the journey and begin our catharsis: this is the third act of the drama.

|

| Toward the second act, the panorama on the coast. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Act II (the recovery of history), Scene I: Mary’s little chapel (from a 19th-century print) |

|

| Act II, Scene II: the Captain’s Castle. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Act I, Scene II: the amusement park. One of the merry-go-rounds. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| The enemy castle in the distance on the hill. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Act II, Scene IV: the Captain’s mausoleum. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

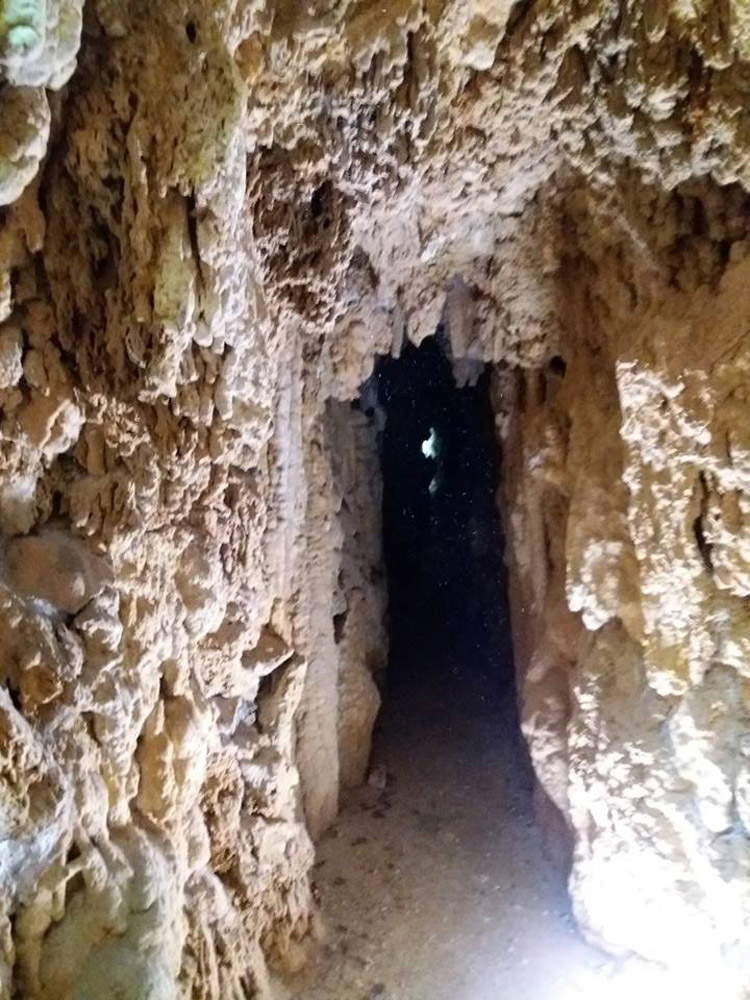

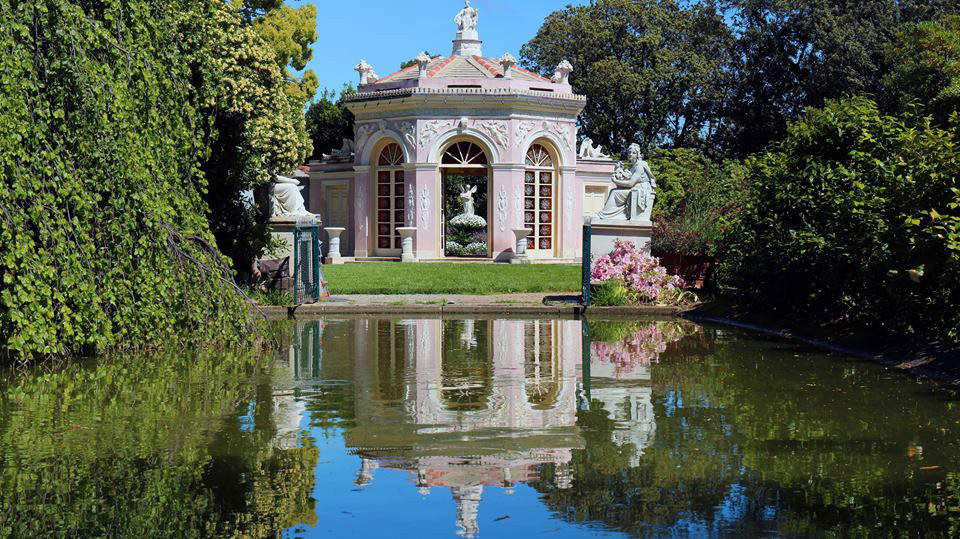

Let’s start with the first scene, a descent to the underworld: the original route conceived by Marquis Pallavicini called for a special Charon to ferry visitors inside the park’s grottoes on a small boat. The grottoes are now under restoration, but we can imagine how evocative it will be, when they are reopened, to venture among these caverns reminiscent of Dante’s inferno: to the initiate, being able to see sin and its consequences firsthand offers a final opportunity for repentance and subsequent redemption. The latter is encountered at the end of the path within the caves: the soul is finally purified and one arrives at the second scene, the Great Lake, that is, the paradise where the souls of the blessed from all over the world have come, as well as the best-known setting in the entire park. Underlining the universality of such a harmonious gathering, we see architecture typical of every part of the world: the Roman bridge, the Egyptian obelisk, the Turkish kiosk, the pagoda. In the center, the temple of Diana (her statue stands out in the center of the building) surrounded by figures of marine deities (all sculptures are works by Cevasco), a symbol of freedom and brotherhood, but also of the continuity of the present vis-à-vis the past and the now rediscovered relationship between man and nature.

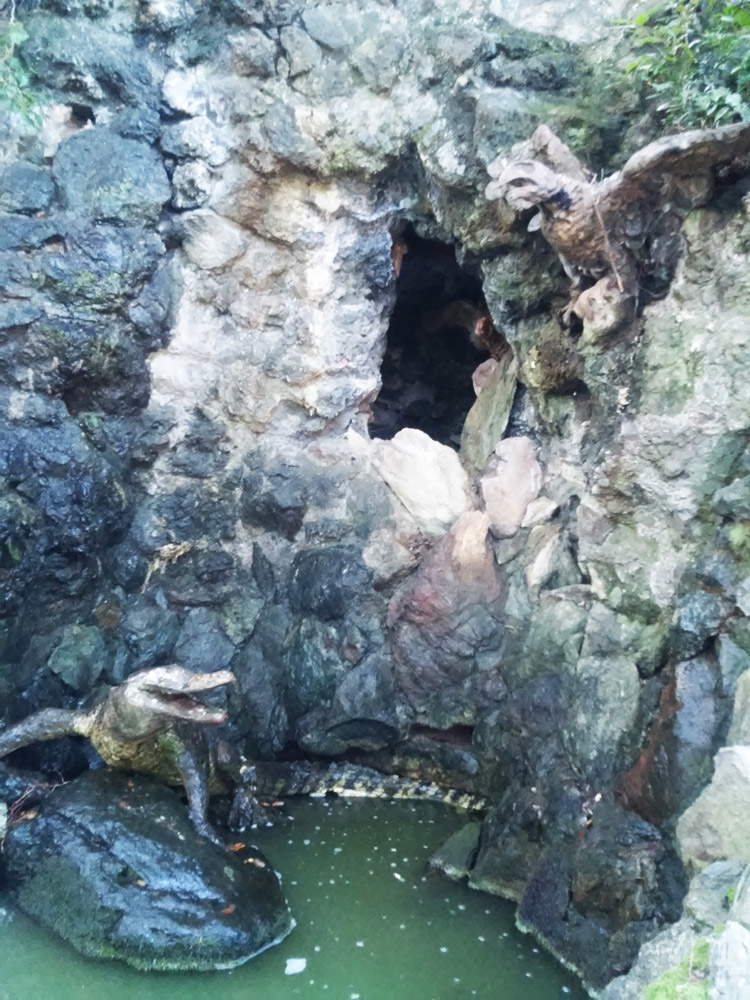

An idyllic setting, which continues with the Gardens of Flora, the third scene: we find ourselves, suddenly, in a lush viridarium at the center of which a nymph, also sculpted by Cevasco, spreads her flowers. We realize that we have been dreaming, and we have awakened in an earthly paradise to which our soul has finally arrived. Thus renewed, we access the last scene, the remembrance: in this portion of the park we find the monument to the Ligurian poet Gabriello Chiabrera (Savona, 1552 - 1638) and that to Michele Canzio, who by their work became immortal, and whose example urges us to reflect on the fact that eternity is achieved by a life of goodness. A series of water plays constitute theexodus of the play and accompany us toward the exit.

|

| Act III (the catharsis), Scene I: the caves/Dantesque hell. Ph. Villa Durazzo-Pallavicini. |

|

| Act III, Scene II: the Great Lake. In the center, the Temple of Diana. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| The Egyptian obelisk. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| The pagoda |

|

| The shores of the Great Lake and, in the background, the Turkish kiosk. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Act III, Scene III: Flora’s Gardens. Ph. Credit Villa Durazzo-Pallavicini. |

|

| The nymph. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Act III, Scene IV: Remembrance. The monument to Michele Canzio. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Exodus: water games. The crocodile and the eagle. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

The splendid complex of Villa Durazzo-Pallavicini, since 1928, to the City of Genoa: Matilde Giustiniani, a descendant of Ignazio Pallavicini, donated it to the community with the condition that the park be open to the public. Since then, in alternating phases, the park of Villa Durazzo-Pallavicini has always respected this will, albeit with some interruptions, for example, when the highway had to be built (which passes right under the park and whose works also involved damage to the complex) or, recently, between 2014 and 2016, when the park underwent major restoration works. And even today, going into the rich vegetation, among the beautiful flowers that we find on the path, among the buildings and constructions that mark the various stages of the initiation in which we participate, is a unique and regenerative experience for the soul and the mind. An experience that you will certainly remember for a lifetime.

Reference Bibliography

- Francesca Mazzino, Michele Canzio, entry in Vincenzo Cazzato (ed.), Atlas of the Italian Garden, 1750-1940: biographical dictionary of architects, gardeners, botanists, patrons, men of letters and other protagonists, Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato, 2009

- Silvana Ghigino, Fabio Calvi, Villa Pallavicini in Pegli: the romantic work By Michele Canzio, SAGEP, 1998

- Cristina Bonagura (ed.), Historic parks and gardens: knowledge, protection and enhancement, De Luca, 1991

- Annalisa Maniglio Calcagno, Gardens, parks and landscape in nineteenth-century Genoa , SAGEP, 1984

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.