Pompeii leaves a vague sense of disquiet and wonder, even today. Having become a space outside of time, to pass through its gates is to enter a dimension different from our own. But why did Scottish director Adrian Maben choose Pompeii specifically for his live performance? And why Pink Floyd? Before we get to the October days of 1972, it is interesting to analyze what was the historical/artistic framework of Pompeii’s rediscovery and development and take a step back.

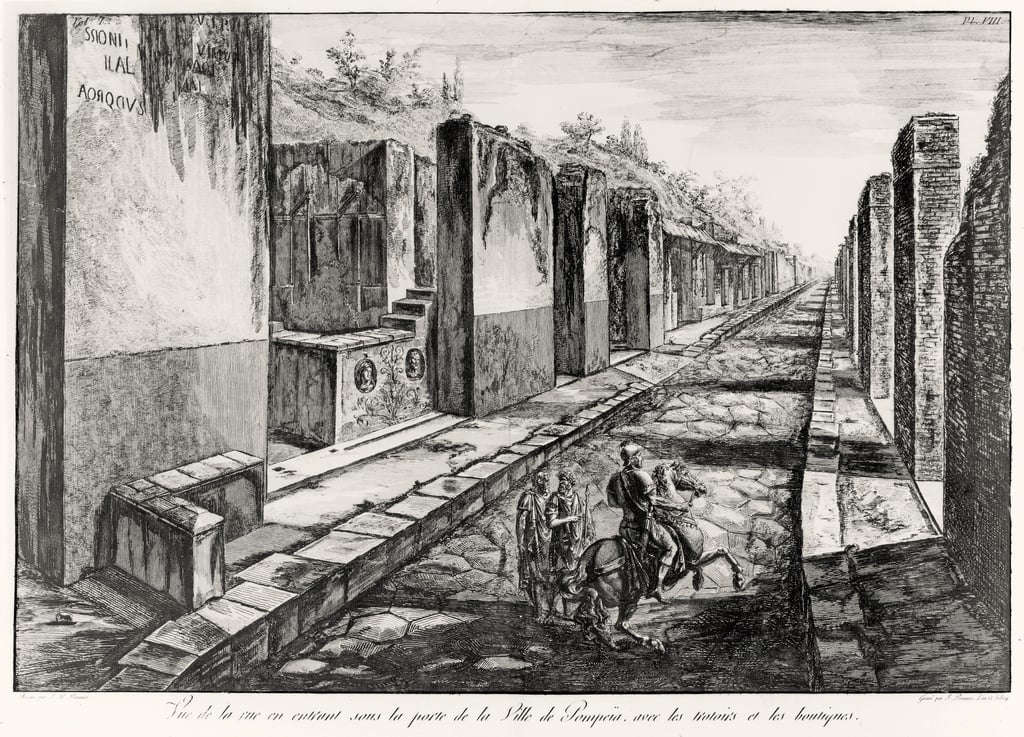

Knowledge of classical antiquity had a decisive breakthrough when in 1738, by means of archaeological investigations, the ancient ruins of Herculaneum and Pompeii buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D. were located. The enthusiasm of the searches for the past places provoked in the various kingdoms of Italy a revival and discovery of excavations: especially in Rome and in the south of Italy, where Magna Graecia had an important development. The newfound interest in the ancient world initiated the publications of entire illustrated volumes that contained reproductions of Greek and Roman antiquities, such as Tommaso Piroli’s Antichità di Ercolano Esposte published between 1757 and 1792, or Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s Le Antichità Romane of 1756. The never-before so widespread growing development for antiquity and publications related to it influenced the birth of a new artistic movement: Neoclassicism. With the development of private and public collections for the purpose of their own appreciation and the art market, Neoclassicism characterized the second half of the eighteenth century and the first two decades of the nineteenth century. Indeed, it had a close relationship with both the established Enlightenment society and Romantic culture. The poetics of the new current carried with it the Romantic sentiment that stirred man’s emotions when faced with the noble grandeur of ruined Greco-Roman monuments, in an ’atmosphere of melancholy sadness that one breathed when observing classical monumental structures.

It is the same feeling Adrian Maben experiences between 1970 and 1971 walking through the streets of Pompeii, enveloped in a silence that manages to pierce the eardrums. “It’s a bit like hearing the silence of the world,” to borrow Magritte’s words. Coming from film studies made in Rome, Adrian Maben, born in 1942, immediately came into contact with the world of Fellini, with the great Italian directors of the 1960s culture and especially with the majesty of the monuments of the Eternal City. A world that he would take to Paris a few years later and of which he would decide to surround himself. And it is there, working on projects about kinetic art, that the director gets the idea of making an art film totally different from everything else that others propose.

At the same time as Maben’s research and his journey into filmmaking, a British band already considered a cult is chasing musical success in Italy as well. They call themselves Pink Floyd, and unlike the Rolling Stones and other bands of the period such as The Who, they are the only ones shrouded in an aura of mystery that makes them evanescent. In 1970 they were chosen by Michelangelo Antonioni to soundtrack his last film, Zabriskie Point. The film’s final scene will remain memorable with their soundtrack Come In Number 51, Your Time Is Up in which the fusion of the mansion’s explosion and Pink Floyd’s melody generate a dynamic outside of space and time. Everything moves and everything stands still in a moment that becomes abstract. Thunderstruck by the band’s metaphysical and almost alien sounds, Maben decides to make an art film in which their music creates a perfect background to the images of De Chirico and those of Magritte (also including works by more contemporary artists such as Christo). The idea does not appeal to the group, and the real breakthrough comes only when the director discovers and visits the ruins of Pompeii.

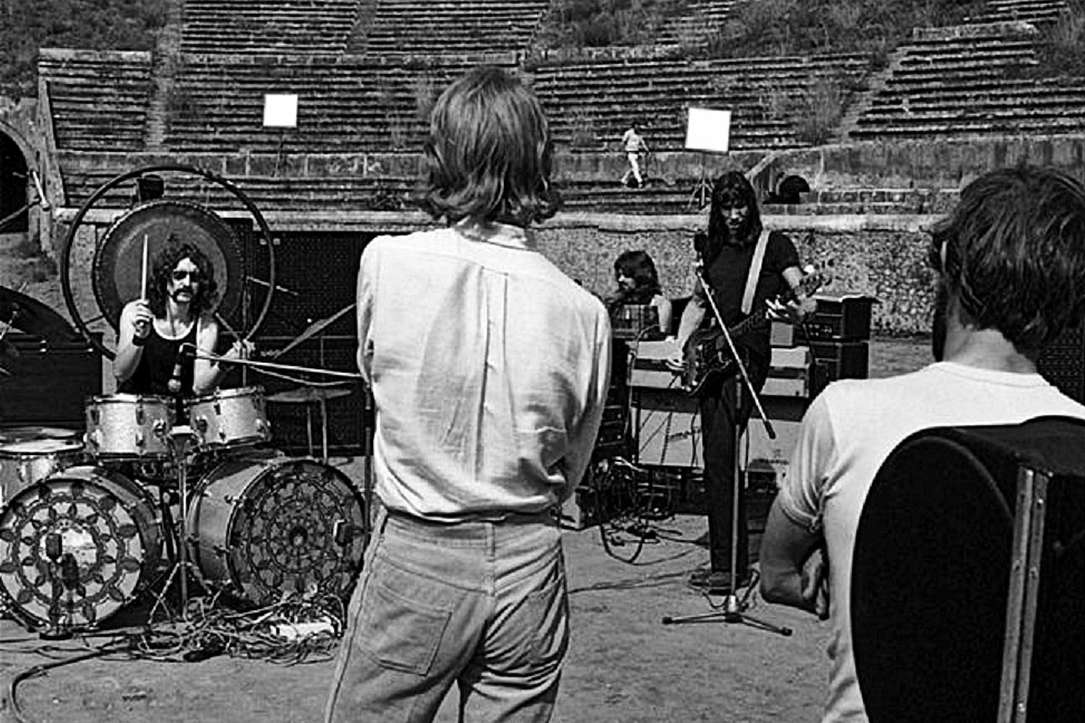

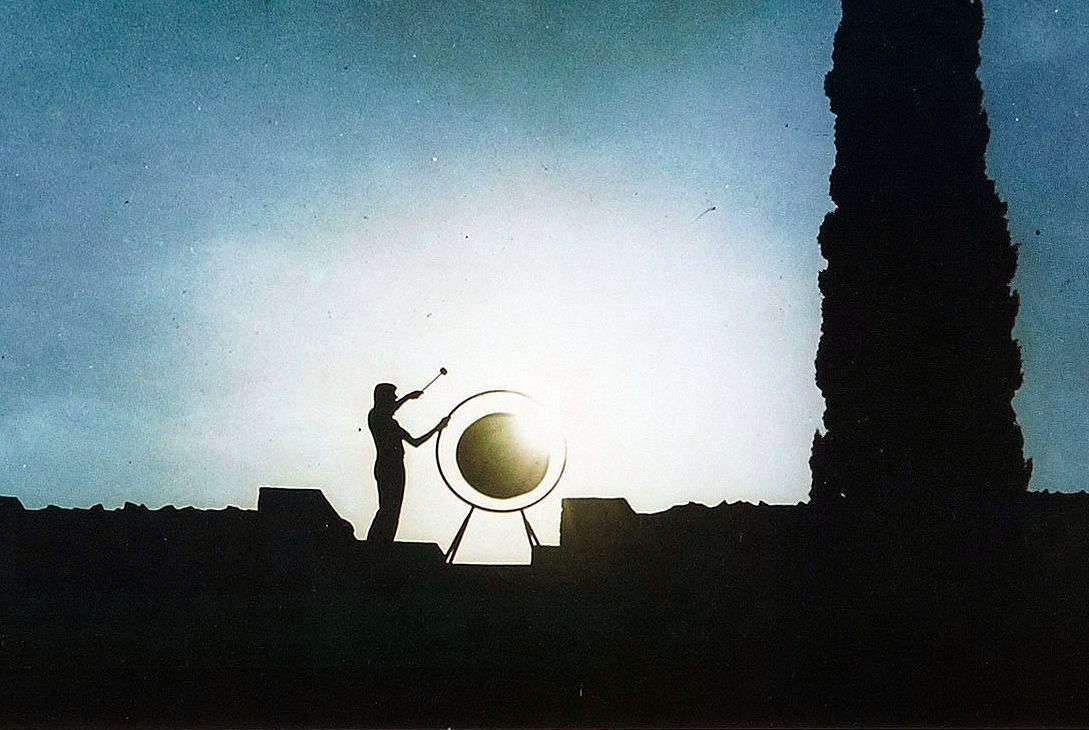

In the silence above him, enveloped by the scent of Mediterranean pine needles, the sound of cicadas, and in the center of the sunlit amphitheater, he has no more doubts. Via De Chirico and via Magritte. He proposes a second idea to Pink Floyd: a live performance in Pompeii, in the center of the amphitheater. The group immediately accepts, but on two conditions: first, no playback. Just their live vocals. The second, however, is the presence of all their equipment. Amplifiers and recorders of rather advanced technology. The director agrees. Adrian Maben cannot miss a beat and, before the live show, decides to go even more into contrast with the live shows of the moment.

Totally in contrast to the great Woodstock music festival, held in Bethel, New York state, August 15-18, 1969, the live show in Pompeii is designed to become the symbol of anti-Woodstock. The irrationality of the soul against reason and sacred silence. Silence given by theabsence of spectators, so it was decided by Maben. Because only the spectres of the past attend the live performance. And through solitude the director decides that his film should reflect feelings of fascination, reverence, fear, splendor. He therefore breaks away from the cliché of the moment in order to create something new. Different in the dynamics of the live performance, the venue and, above all, the artistic purpose. For Pink Floyd and their time-penetrating sounds, there remains only Pompeii with its sublime and ghostly nature. Highlighting the city destroyed by Vesuvius is surely unprecedented for a band. Their music would be framed by the ruins and the atmosphere of damnation that continues to hover over the site.

Jacques Boumendil,

Jacques Boumendil,

It is October 4, 1971. After days of difficulty, an electric cable hundreds of feet long, finally bringing power to Pink Floyd’s expensive recording facilities, winds its way from the back of the sanctuary of the city of Pompeii. It proceeds all the way from the town to the Roman ruins, ending its journey in the amphitheater. Then the action. A forward tracking shot to the amphitheater and soon after the live music begins as the crew records the four young men and their instruments: the live show begins with Echoes pt. 1, the masterpiece that has no memory. The figures become increasingly distinct as the camera gets closer, although David Gilmour, Roger Waters, Richard Wright, and Nick Mason are easily recognizable.

Of great importance to the film’s editing are the backlit shots of the boys making their way in solitude through Pompeii’s excavations and Pozzuoli’s Solfatara, an active volcanic crater in the Phlegraean Fields. In a quiescent state for at least two thousand years, it still maintains an activity of sulfur dioxide fumaroles and jets of boiling mud. The group plunges unceremoniously into the sulfurous vistas of a different world. A place of mud bubbles and magmatic rocks, where the earth lives, inhales and exhales poison giving suggestions to make one think of standing before the gates of Dante’s Inferno.

Jacques Boumendil,

Jacques Boumendil,

Alternating with the images of the boys walking, there are shots to the silent stone faces of the ancient Pompeian sculptures, which evoke moments of great suggestion and fascination. These are key images for the construction of the film, which will be divided into two parts: the first half, which includes Echoes pt.1, One of These Days and A Saucerful of Secrets, and the final Echoes pt.2, is recorded directly in Pompeii. The second, on the other hand, at Europasonor studios in Paris a little later, between December 13 and 20, 1971. In that week of live filming, Pompeii becomes the silent companion of those present, immerses them in a context of reflection, mystery, and Pink Floyd’s music is elevated to a higher plane. Different, Divine. Incomprehensible at times, it does not come from the earthly plane nor from the present world.

While Woodstock represents the freshness of new ideals of thought and expression carried by the wave of the ’68 revolution, Pompeii represents a history crystallized beyond time. A rediscovery of the ancient clad in a religiosity accessible only to the band. Only Pink Floyd is allowed to approach it, to understand it, to brush against it; to them Pompeii gives its echoes, its memory, and they return its energy to the world: shaped, more mysterious, ever elevated through a unique, unprecedented experience. A eulogy to that beauty that only Adrian Maben’s eyes were able to capture among the reddish streaks of the sunset sky over Pompeii.

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.