The expressive power of Wiligelmo’s Stories of Genesis, the masterpiece of Romanesque sculpture that decorates the facade of Modena Cathedral, has very few equals in the history of art: this was the conviction of Francesco Arcangeli, among the greatest experts on Emilian art over the centuries, and in particular of that charged, dramatic, almost popular strand of artistic expressions that matured along the Via Emilia, which in his opinion drew its origin precisely from Wiligelmo’s art. “Man feels, first of all, obscurely his own body as a physical entity,” Arcangeli wrote in his seminal text Natura ed espressione nell’arte bolognese-emiliana, “and no one in art, more than Wiligelmo, has sensed and expressed the inevitability of that presence and spirit [....] a vegetable, human, animal tangle, so slow, pressing, viscous, impenetrable, a tangle so totally deprived of pause and breath.” The drama unleashed by the slabs that Wiligelmo sculpted for the Modenese cathedral is in fact, as will be seen later, an all-human drama, underscored by the intense naturalism of a representation in which it is the divine that “is involved in the dark and often wretched affairs of created beings, rather than drawing them into its supra-human sphere,” Arcangeli wrote again. It is from here, from these marble sculptures, from these Romanesque masterpieces that the adventure of Emilian art begins. Wiligelmo, however, could not have known this.

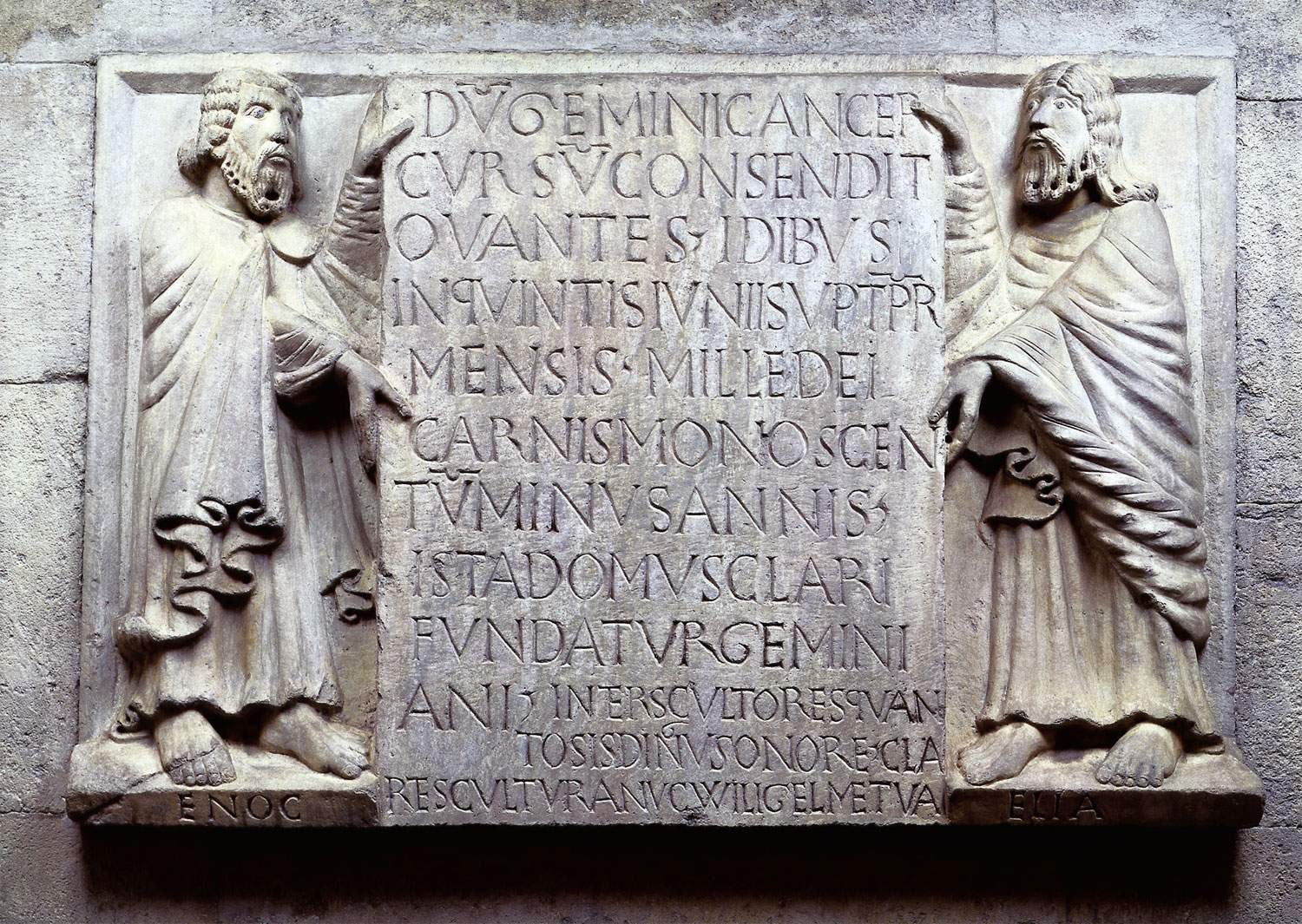

The author of these works lived between the 11th and 12th centuries, but we have very little information about him. We can imagine him to be originally from the Como area, and he is certainly one of the first artists in Italy to leave his name on the works they produced. In particular, his name is known thanks to an epigraph held up by the prophets Enoch and Elijah placed on the very facade of Modena Cathedral, where the date of the founding of the building of worship appears (1099, rendered with the formula “One Thousand and One Hundred minus One”), and where the author of the sculptures is praised: “Du(m) Gemini Cancer / Cursu(m) consendit ovantes ibidus / in quintis Iunii sup. t(em)p(o)r(e) / mensis Mille Dei / Carnis Mons cent/tu(m) minus annis / iste domus clari / fundator gemini/ani. Inter scultores quan/to sia dignus onore cla/ret scultura nu(n)c Wiligelme tua,” meaning “As Cancer passes the course of Gemini, in the time of the month of June on the fifth day before the Ides, the year of the incarnation of God One Thousand and One Hundred minus One was founded this Dome of the great Geminianus. How worthy among sculptors you are of honor is clear now, O Wiligelmo, by your sculpted works.”

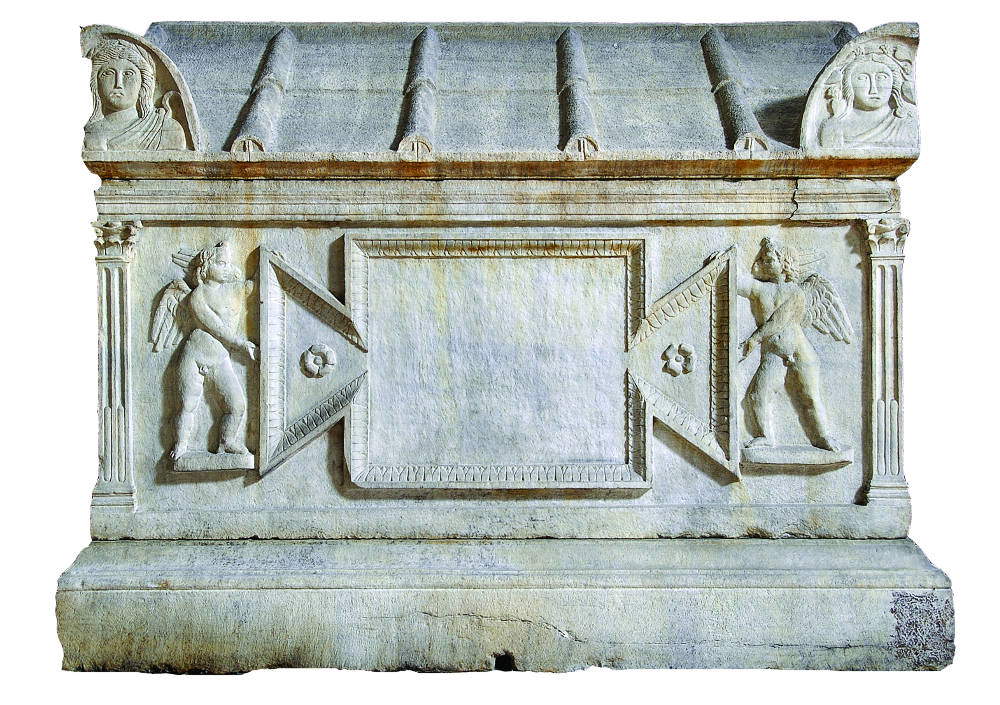

Wiligelmus carved the Stories of Genesis on four slabs, using reused material: in fact, in 2012, during the restoration of the façade of Modena Cathedral, it was ascertained that the artist had worked on slabs that had already been carved, probably dating back to the 8th century, and possibly coming from the church on the site of which the Modena cathedral was built, for which construction material taken from the previous house of worship was used. The artist turned them over and carved the smooth face, the one that had not been used by the artists who had carved them before him. Today Wiligelmo’s slabs are all placed symmetrically on the façade: two surmount the side portals, while the other two flank the main portal. However, we do not know theexact original location of the Lombard artist’s works. They were certainly not placed as we see them today, since the opening of the side portals is later than the time when Wiligelmo worked on his slabs: it is possible, therefore, that the slabs were recessed in pairs on either side of the main portal. In 1967, Arturo Carlo Quintavalle, in an essay on Wiligelmo, formulated another hypothesis instead: these could be reliefs that decorated the pier, that is, the balustrade of the presbytery, later replaced in the late 12th century by the present one, which features a series of carved slabs, made by Po Valley artists in the second half of the 12th century (the whole has been extensively remodeled, however, and the present appearance is the result of the recomposition that followed the restorations carried out in the late 19th century and the beginning of the following century). Following Quintavalle’s theory, a debate arose between those who considered his theory plausible and those who continued to believe it more likely that the slabs were originally placed on the facade: the problem, however, has not yet been resolved. The aspect on which all scholars agree is that it is not credible that all of Wiligelmo’s works that we see today on the facade of Modena Cathedral (in addition to the Genesis slabs, in fact, the already mentioned epigraph with the prophets Enoch and Elijah, also his work, and then the symbols of the Evangelists, the relief with Samson and the lion, the genii regifiaccola and the prothyrum reliefs): some of these must have originally been part of the interior decorative apparatus of the Modenese cathedral.

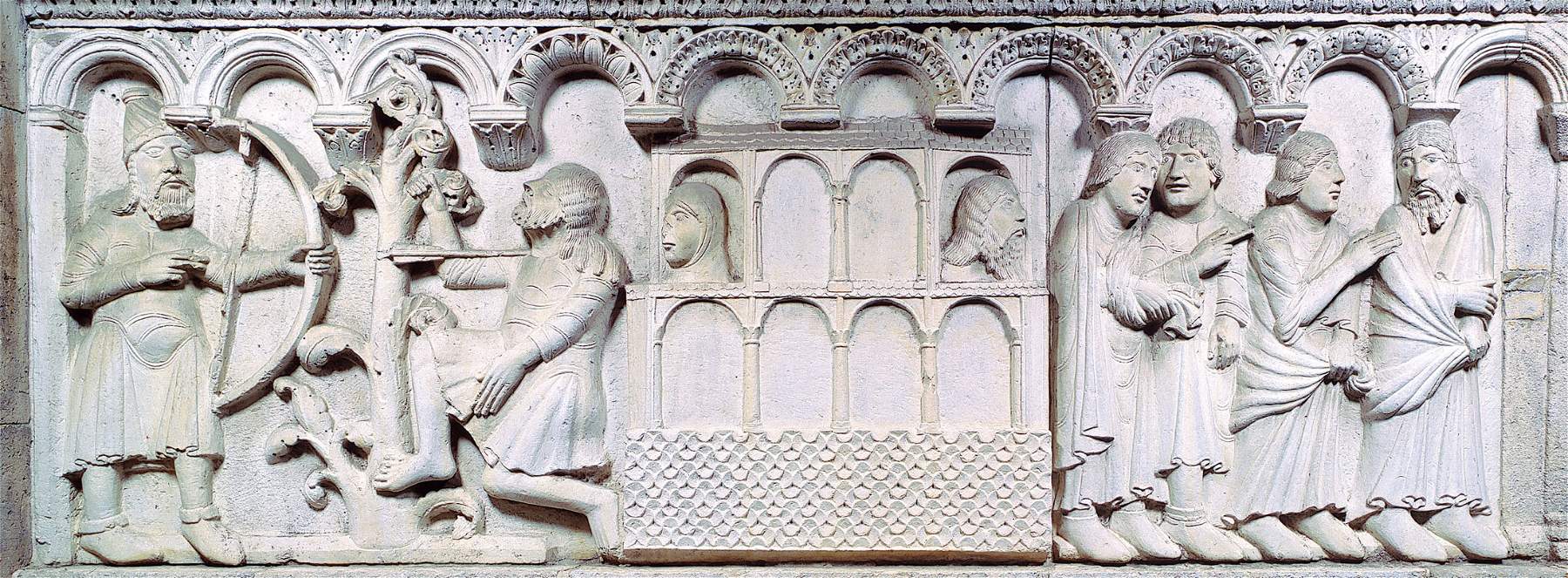

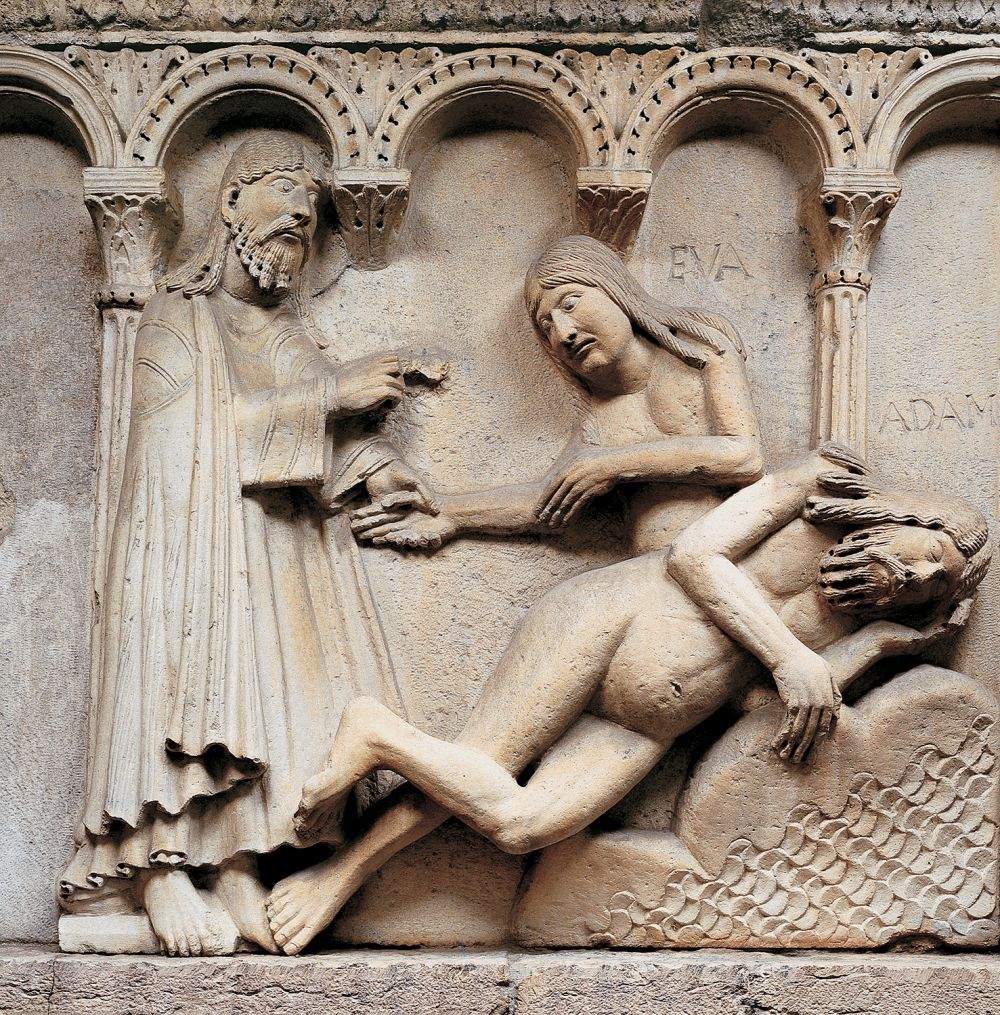

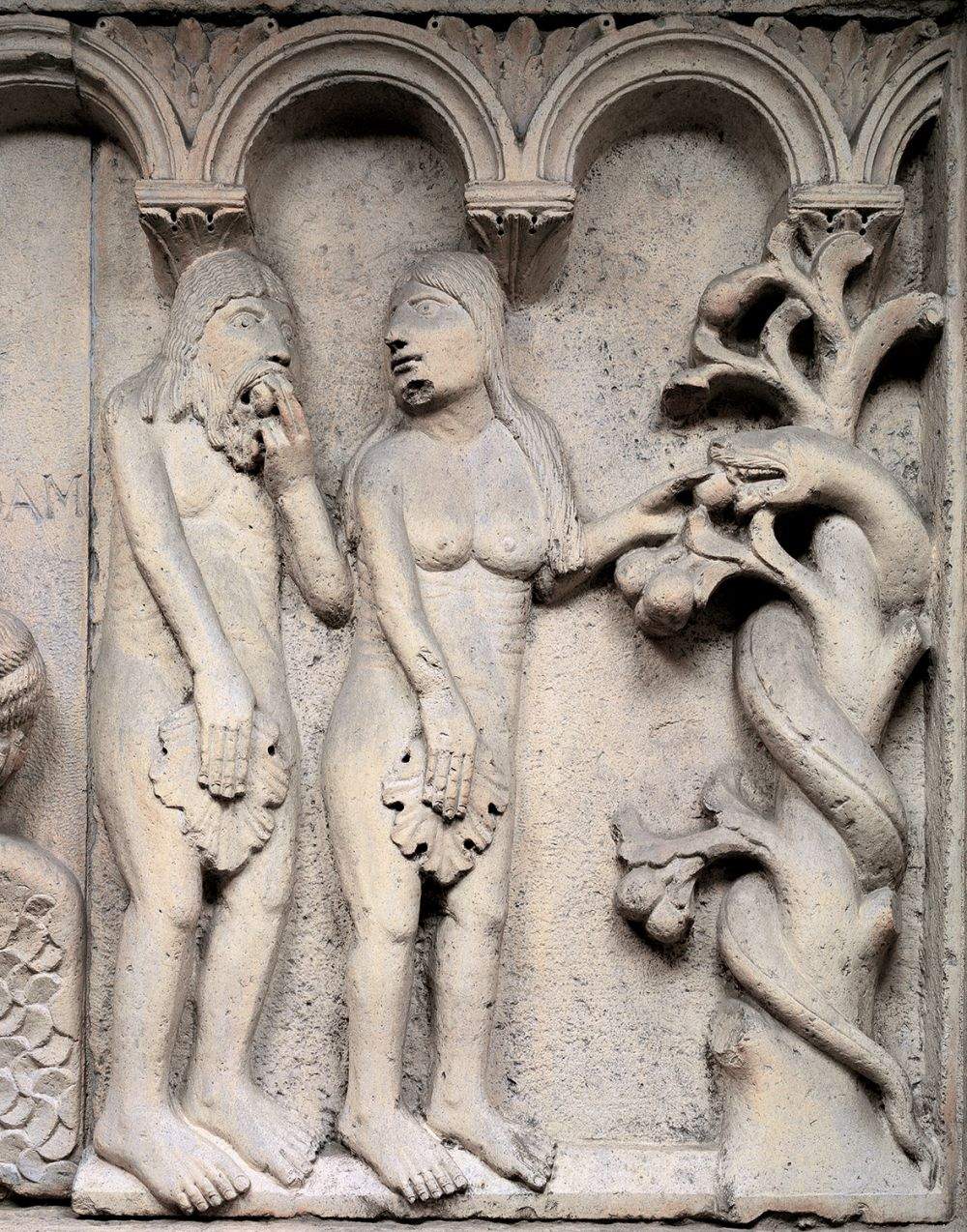

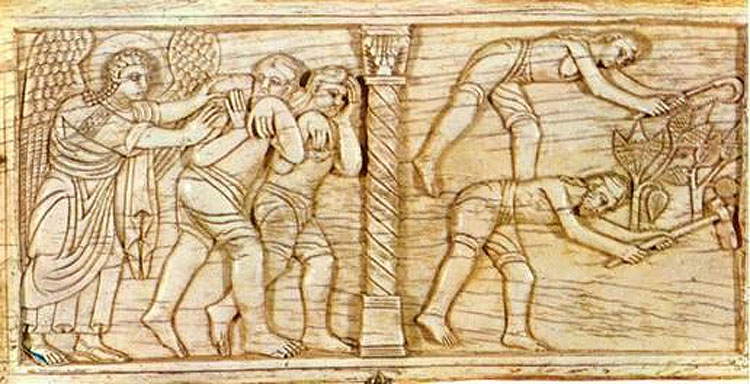

The slabs are divided into individual episodes, thirteen in all, punctuated by the small arches resting on corbels that frame all parts of the story (and in some parts the columns can also be seen). The first slab is the only one with four scenes: there is the Eternal Father, holding a book bearing the inscription “Lux ego sum mundi, via verax, vita perennis” (“I am the light of the world, the true way, the everlasting life”) in a mandorla supported by two angels, followed by the creation of Adam, the creation of Eve, and original sin. In the two scenes of the creation of the progenitors, God is always depicted in the same pose, sideways, represented as a mature, bearded, long-haired man (exactly like Adam). Note, moreover, how Eve is depicted without breasts in the creation scene, while Adam appears with hidden genitals: this is probably an allusion to their primal innocence. In the next scene we see her with conspicuous breasts as she plucks the fruit from the tree of Good and Evil (note the tempting serpent handing it to her) and Adam is eating it. In one episode, Wiligelmus also included the next moment, when Adam and Eve, after sinning, realize they are naked (so here they cover themselves with fig leaves). In the second plate, the progenitors, in the same pose, are the protagonists of the scene of God’s rebuke and, in the second scene, of the expulsion from the Earthly Paradise: in this episode, however, they are visibly distressed as they are expelled from the Garden of Eden, and out of affliction they hold up their heads with their hands. The third scene is that of work: Adam and Eve, now on earth and clothed, are hoeing under a tree. “The first two plates,” writes scholar Erika Frigieri in introducing the theological significance of the narrative, “are [...] dedicated to the creation of the progenitors, their sin and the consequences of this: work is seen not only as punishment, but also as a way to salvation. Work understood as a means of redemption and the way to redemption also explains the very rare iconographic scene in which Eve is depicted working instead of the much more common one in which she spins and suckles her children, an allusion to the divine curse.”

We then turn to the third plate: the first episode is the presentation of the sacrifices to God by Cain and Abel (Wiligelmus, however, chooses not to narrate the moment of Cain’s rejection of the offering), then follows thekilling of Abel by Cain and the encounter between Cain and the Eternal Father, who imposes his sign on the murderer so that that he be recognized and not suffer revenge (this gesture, Frigieri again notes, “also has a meaning of comfort, of reassurance, which rightly fits into the salvific program of the facade”). In the last slab we witness three more episodes: thekilling of Cain by the hunter Lamech (depicted with his eyes closed as he is blind), Noah’s ark (we notice the faces of him and his wife poking out of the hull), and the exit of Noah and his sons from the ark. The shape of the ark is reminiscent of that of a church: another reference to the symbolic meaning of the cycle, dedicated to the theme of salvation. For the same reason, Wiligelmo’s plates end with the scene of the exit from the ark: it alludes to the Covenant that God establishes with humanity, through Noah, for the salvation of human beings.

According to scholar Chiara Frugoni, Wiligelmo would not have drawn his narrative directly from the book of Genesis: rather, his source would have been, in his opinion, the Jeu d’Adam, a liturgical drama written in Anglo-Norman (a dialect of medieval French), in octosyllables and decasyllables, which tells of the fall of humanity as a result of original sin, and the subsequent redemption. Supporting this hypothesis would be timely cross-references: beyond the precise narrative sequences (the scene of work in the fields immediately after the expulsion, for example, or that of sin in which Adam appears much more reluctant than his companion), there are hits such as the inscription with the words addressed by the Eternal Father to Adam and Eve after the original sin (“Du(m) de/a(m)bula/ret Domi/nus i(n) pa/radisu(m),” or “While the Lord walked in the garden”) taken not from the Bible, but from the Jeu d’Adam itself. A chronological problem would remain to be solved, since Wiligelmus’ activity in Modena is documented between 1099 and 1100, while the Jeu d’Adam would date from the mid-12th century. Frugoni puts forward the hypothesis that the Jeu, before being put in writing in the middle of the century, must have known a long oral tradition, or at any rate be transcribed on codices that have not come down to us. This hypothesis, however, does not close the question. Scholar Sonia Maura Barillari writes that several problems still exist: “whoever determined what should be the words to be carved in the scrolls of parchment wielded by the Creator as he pronounces the condemnation of Adam and Eve first, that of Cain later - identical to those with which the fourth and seventh responsories of the Jeu begin - should have had a written version of the ’work very close to it in form, and not only in content, but predating it by at least fifty years, forcing us to postulate a diffusion of scenic representations of liturgical or ’para-liturgical’ subject matter, and of the texts intended to support them, in the Po Valley Italy of the time not otherwise attested either directly or indirectly. As for any oral transmission - either of an actual text or of the memory of a performance that someone may have witnessed - it would not have allowed or guaranteed, due to its fluid and fluctuating character, faithful literal quotations such as those mentioned above.” More likely, then, that the author of the Jeu d’Adam and Wiligelmus drew on additional common sources, for example, according to Barillari, theOfficium of the Sunday of Septuagesima (a solemnity celebrated on the sixty-fourth day before Easter and marking the beginning of Carnival Time), or the Sermo contra Judaeos, a sermon attributed to one Pseudo Augustine and which had some circulation at the time.

The modernity of Wiligelmus’ work is also evident from the reference models: the artist looked both to the art of his contemporaries and toclassical antiquity, which he revisited with great originality, beginning with the epigraph itself with the prophets Enoch and Elijah (who, moreover, having been assumed directly into heaven, and thus unaware of death, were seen as the most credible “witnesses” to the goodness of the eulogy to Wiligelmus), based on the funerary genes of the Roman sarcophagi (in Modena itself, it is possible to see the example of a model that Wiligelmus punctually takes up in the relief with the prophets holding up the inscription: it is the so-called “Sarcophagus of Matteotti Square,” a classical funerary monument, datable between 150 and 170 AD.C., and today preserved at the Estense Lapidary). In the Genesis slabs (but the discussion could be extended to all of Wiligelmo’s works), Quintavalle wrote, “above all the relationship with Late Antique culture in the north appears evident: a similar expressiveness, a realism concentrated in the detail, a precise plastic attention and, again, a similar distribution of figures in space.” The structure with arches and columns is also a reinterpretation of ancient sarcophagi, particularly of a type widespread in early Christian art, in which narrative scenes were rigidly divided into compartments separated precisely by architectural structures: a particularly well-known example is the sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, one of the oldest known Christian sarcophagi, a 4th-century work now preserved in the Museum of the Treasury of St. Peter’s in the Vatican. However, Wiligelmus decided to renew this model by creating a continuous narrative, marked by a strong rhythmic scansion (the figures are thus inserted one after the other, as if on top of a ribbon) within an open field that no longer preserves the rigid separation that in ancient sarcophagi was guaranteed by the columns, so much so that in most scenes there is no longer even correspondence between figures and arches, the syntax becomes free, the episodes have lengths that are not always regular. It is also likely that Wiligelmus was well acquainted with the figurative culture of his time: his idea of depicting, in the scene of the work of the progenitors, the figure of Eve intent on hoeing has often been presented as innovative, but it is actually a motif attested even before Wiligelmus, as noted by the aforementioned Barillari, who cites the miniatures of the Bamberg Bible (from the mid 9th century) and the Aelfric Paraphrase (mid-12th century), as well as the ivory antependium now in the Salerno Cathedral Museum (made around 1090), where Eve is similarly depicted working the earth together with Adam.

However, Wiligelmo’s figures lack anything of the classically understood ideal proportions (one can at most see hints of them in the draperies of the clothed figures), that is, they are not affected by the grace that could be appreciated in classical statuary: the proportions of his figures do not care to be balanced and harmonious, although it is clear that the artist tries to make the bodily dimensions of his figures as believable as possible, and above all he intends to make his figures expressive; they emerge with a strong plasticism; they are figures that have a tangible, evident weight. Just by way of example, look at the figures of the two angels holding the mandorla with the Padreterno: Archangels noted that they really struggle, as opposed to the angels of Byzantine art who appeared imperturbable instead. The disproportions and lack of grace in Wiligelmo’s figures are not only to be explained by virtue of the fact that the artist had in mind mainly late antique works from the Po Valley area, and thus already far removed from the balance and harmony of classical statuary, or because he had to respond to practical needs, which could also motivate the disproportions (in other words, the artist had to imagine his figures for a view from below). His works, which knowingly reject the serenity of classical art, also had to respond to a symbolic need: as mentioned in the opening, that of bringing to life a deeply human drama.

And it is precisely the image of the human being that asserts itself in the Genesis plates. An image that involves numerous aspects, numerous representations that transcend and transcend material or everyday reality, as Erika Frigieri has well noted, identifying in Wiligelmo’s masterpiece five different imaginaries: there is a biblical one, which is at the same time also historical, since for Wiligelmo’s contemporaries the sacred text was the “first and essential source of inspiration and meaning,” as well as “holy history.” There is then an ancient imagery, that of the conscious quotations that the artist deploys in his slabs, and then again the imagery of the world and nature that refers to the human being, the earth, animals, and plants, to continue then with the imagery of the human body (evident especially in the scenes that have the progenitors as protagonists), in which is also included the imagery of attitudes and gestures, and finally the imagery of writing, attested by the inscriptions that accompany the entire narrative. In essence, in the Genesis plates we witness the “affirmation of man, his tastes, his pleasures, as well as his fears, his vocation, which is expressed in the imagery of the facade. There is therefore an anticipation of what will be the humanism of the 12th century, and Wiligelmus’ greatness consists in announcing the importance of a century in which his imagery will become reality.” A statement that is expressed above all through relief, through the weight of the characters in Genesis. Francesco Arcangeli said it well in a lecture dedicated to the author of the slabs, even considering it a popular, overbearing, violent and contesting statement, typical of a “terrible revolutionary,” as the scholar called the artist: “Romanesque, as it is configured in a great Lombard sculptor named Wiligelmo and working in Modena at this particular juncture, means (whether Wiligelmo knew it or not, but I believe he knew it in his own way) that earthly life had its more or less obscure rights and had a power of presence that medieval civilization had forgotten or put in parenthesis. I think it is hard to deny this interpretation. If one wanted to put it in Freudian or Jungian terms, one could say that it is the darkness of man that medieval civilization had bracketed in order to affirm a super ego of a mystical kind, and instead this is the consciousness of this darkness of man that has its own physical life, strenuous, difficult, painful or not painful, but which nonetheless exists.”

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.