Andy Warhol (Pittsburgh, 1928 - New York, 1987) was an emblematic figure in American painting, the father of Pop Art. Painter, sculptor, photographer, filmmaker and band producer changed the very idea of the artist, who for the first time became an entrepreneur of himself. Shy and haunted by the idea of deeming himself ugly, Warhol was endowed with uncommon communication skills and keen powers of observation, all skills that enabled him to transform his life and build an image as a “star” before he was an artist.

His artistic vocation was born as a child when, following a serious illness, his mother gave him the necessities for drawing. He began working in New York as an advertising graphic designer at some magazines such as: Vogue, Harper’s Bazar and Glamour. it was from the world of advertising communication that he landed in art, elaborating an impersonal language aimed at making a type of art that was an “objective” record of reality. To this end, as well as to initiate a serial production of his works ( seriality is one of the hallmarks of Andy Warhol’s art), the American artist used industrial production techniques such as screen printing on canvas (an artistic printing technique that uses a textile, steel or nylon support as a matrix).

Warhol is also known for creating the Factory, a place where emerging artists and superstars of the period converged, which also became famous for avant-garde parties (in fact, it was said that a party without Andy Warhol was not really a party). Behind this “star,” however, lay a far more shy and elusive personality. On one side was the man and the artist wearing a mask to keep a proper distance from the world, and on the other side was the man and his weaknesses.

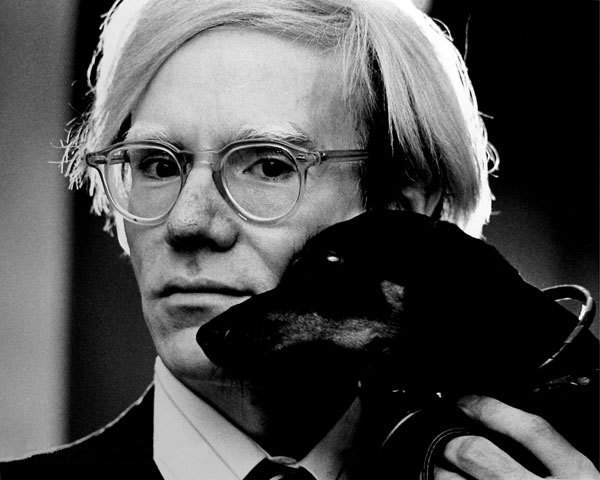

|

| Andy Warhol photographed by Jack Mitchell |

Andy Warhol, a pseudonym for Andrew Warhola, was born in Pittsburgh on August 6, 1928, the last of three children of Ondrej Warhola and Júlia Justína Zavacká , both Czechoslovakian immigrants. The artist showed his artistic talent early on and studied advertising art at Carnegie Institute of Technology in his hometown. After graduation he moved to New York: the metropolis offered him excellent opportunities to establish himself in the world of advertising communications, because it gave him the opportunity to work for magazines such as Vogue and Glamour as an illustrator. In 1952 Warhol exhibited for the first time, at New York’s Hugo Gallery, bringing fifteen drawings inspired by the writings of writer Truman Capote, with whom he would remain friends for a long time. That same year his mother Julia Warhola moved to New York, where she would live with her son until 1971. The artist had a very deep relationship with his mother, who is considered one of the most influential people in his life and who worked closely with Andy. Two years later, he held his first solo exhibition at the Loft Gallery, also in the Big Apple.

In the early 1960s, Warhol executed his first drawings devoted to the world of comic books and advertising. It is important to point out that in these years the American art scene was dominated by actionpainting (“action painting”), a technique in which color was dripped spontaneously, at other times it was thrown onto the canvas. The artist exploited “chance,” and the work arose not from an a priori plan but from a process of improvisation. Warhol deviated from all this and chose to reproduce the reality around him in the coldest and most detached, industrial and massified way possible. A strong influence on him was the exhibition he saw at Leo Castelli Gallery of the American pop artist Roy Lichtenstein (New York, 1923 - 1997), whom he did not know at the time but was deeply fascinated by. In 1962 he began to use the silkscreen technique on canvas and took the principle of unlimited reproducibility of the work of art to its extreme consequences. He also changed the themes of his works: soups in boxes, Coca-Cola bottles and detergents. The 1960s were the years in which Warhol established himself: in 1962 he exhibited his Campbell’s soup cans for the first time at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles, and two years later he had an exhibition at the Leo Castello Gallery in New York. During this period he exhibited a number of works at the Salomon R. Guggenheim in New York and at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art, and meanwhile an article published in Time cited him as a “pop artist.” In fact, these were the beginnings of Pop Art.

The spaces of Andy’s home were no longer sufficient to contain a burgeoning creative activity, so in 1964 he established his studio at 231 East 47th Street, in the spacious premises that would later be named Factory: a center of artistic production not far removed from the spirit of medieval workshops, in which the master lived with his students and showed them what they should and could do. From here passed the brightest and most open minds of the “Big Apple” such as singers Jim Morrison, Bob Dylan and David Bowie, writer and actor Truman Capote, or even artists Jean-Michael Basquiat and Keith Haring. They all collaborated on silkscreen prints and lithographs. It was at the Factory that Warhol’s first films such as Sleep and eat (1963), in which a poet sleeps for six hours, or Empire (1964), which depicts the same image of the Empire State Building skyscraper for eight hours. Film productions of some public success also resulted, including Trash (1969), about the lives of young drug addicts.

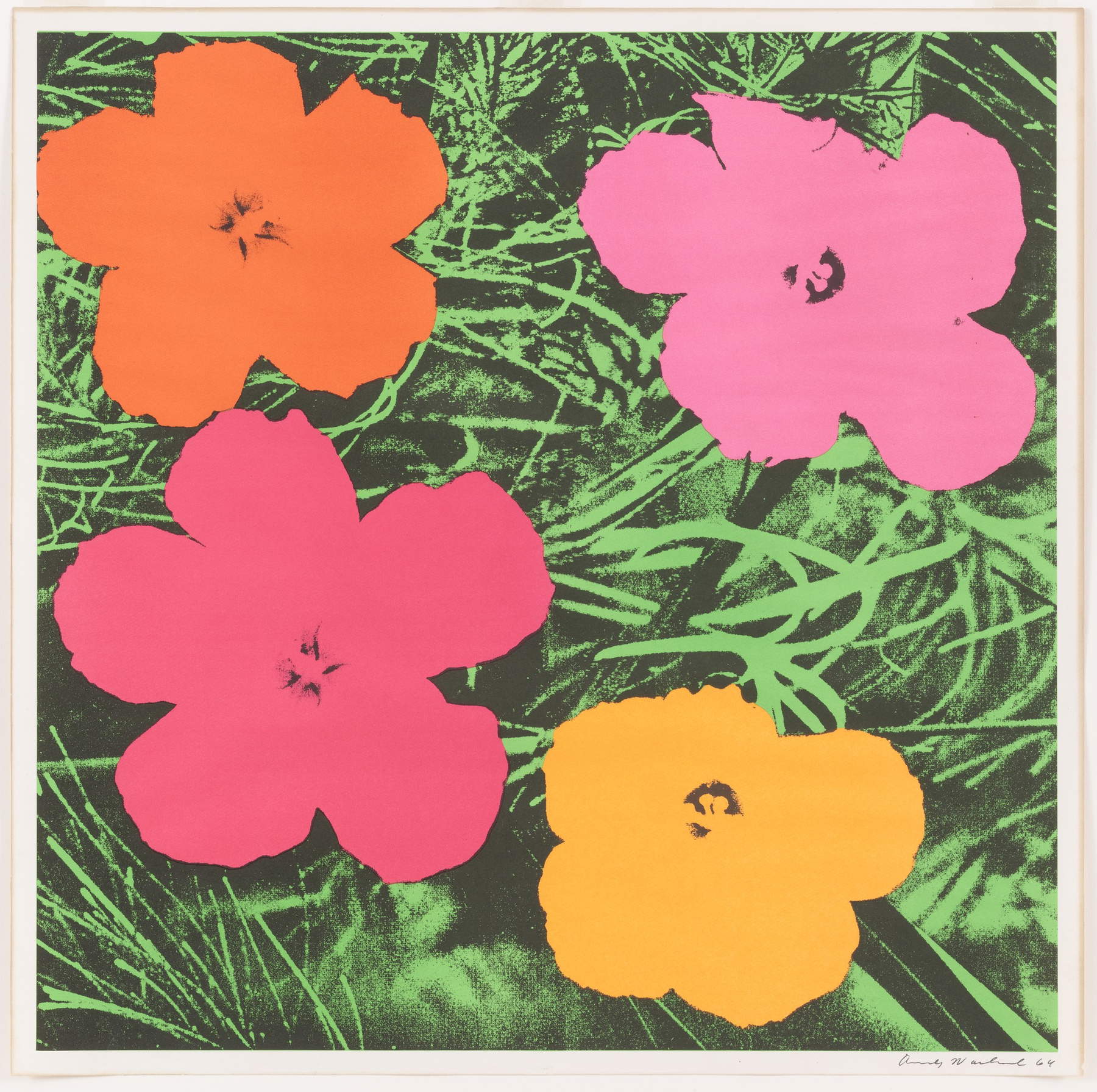

In 1965 came the first Paris exhibition, devoted to Flowers (1964) at the Ileana Sonnabend Gallery, in which Andy described himself as “a retired artist” who was thinking of turning to film. A few years later, 1968, Warhol was wounded with a series of gunshots by feminist Valerie Solanas. The incident damaged all of the artist’s major internal organs and profoundly scarred his life, as his friend and assistant Pat Hackett recounted, “since that June 3, ’68 Andy has considered himself a man officially returned ’to life from death.’” In the 1970s, Andy began receiving a large number of outside portrait commissions. Among the clients: singers Mick Jagger, John Lennon, Diana Ross, and actresses Brigitte Bardot and Liza Minelli. During this period he published a print depicting Richard Nixon (at the time a presidential candidate against George McGrove), with the inscription “Vote McGroven,” an explicit reference to the ongoing presidential election contention. Beginning with this stance Andy was constantly under the scrutiny of the International Revenue Service i.e., the U.S. tax agency. In 1975 The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (from A to B and Back Again) was published, a book full of quotations from the “king of pop” on love, sex, beauty, time and death, and a little later the artist made the famous Self-portraits with Skulls (1978) and the Shadows series (1978) and Oxidation Paintings (1978). In the early 1980s the American artist began working on a number of television programs: Fashion, in which once a week with friends from the Factory but also emerging artists and new rock stars would talk for half an hour; then there was also Andy Warhol’s TV, in which Andy was paradoxically absent; from 1985 he studied a program for the television channel MTV, entitled Andy Warhol’s Fifteens Minutes, which in the title took up the most famous of his maxims: “in the future everyone will be world famous for 15 minutes.” The “king of pop” died on February 22, 1985 at the age of 52 from complications that arose after gallbladder surgery. After the funeral, during which artist Yoko Ono gave a speech, his body was buried alongside that of family members in a cemetery on the outskirts of his hometown of Pittsburgh.

|

| Andy Warhol, Marilyn Monroe (1967; silkscreen print, 91.5 x 91.5 cm) |

|

| Andy Warhol, Brillo Box (1964; synthetic polymers and silkscreen on wood, 43.3 x 43.2 x 36.5 cm; New York, MoMA) |

|

| Andy Warhol, Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962; acrylic and enamel on canvas, 32 panels, 50.8 x 40.6 cm each; New York, MoMA) |

The main feature of Andy Warhol’s works, what made him famous, was the seriality with which he depicted objects and people that became the icons of the American way of life. The artist posed toward the world as a machine that coldly and impersonally records the reality around him, so the best way to express this artistically was to use the silkscreen technique, the only one that allowed him the effects of objectivity, since the “artist’s touch” was not necessary. He used mechanical systems (the machine cannot lie) to recapture the mechanicalness and seriality of all 20th century living. Andy Warhol is the exemplary case for understanding what happened in the 1960s, and to do so, as the artist himself stated, one need only look at the surface of his works. The works of the American artist became true icons: Marilyn Monroe to Mao Tse-Tung and many others. For Warhol it was the performing technique that was important rather than the act of creation itself, and the technique became an industrial process. Actress and diva Marylin Monroe constituted one of the best-known subjects of Warhol’s portraits, who, after the woman’s death and aware of her importance in the collective imagination, began to take an interest in her. The artist, starting with a famous photograph of the diva, reproduced a series of mechanically “separated” images, as the title Shot Orange Marylin (1964), or “Marylin separated in orange,” states.

This was not actually a true portrait, but rather a reproduction of her public image, the one disseminated by the mass media to please admirers. What interested Warhol was the way communication was transformed, and the artist himself never took an ethical stance: in fact, what he thought about in private is not known (indeed, Warhol was one of the most ambiguous artists in art history). He painted, as he had to say in an interview, “what you see every day” but also what the person or thing, becomes the object of collective adoration. Equally famous is the Death and Disaster series of which traffic accidents such as White car Crash 19 Time (1963) are a part: the image on the white background of the canvas retains the few and distinct industrial colors of the low-quality photographic reproduction of the newspaper from which it is taken, and it is precisely the serial reiteration that changes the meaning expressed by the original image, making it become an almost “banal” motif. On the other hand, the tragic content of the image had already been weakened through mass circulation in all newspapers: the image will soon be forgotten, and will be replaced by “ready-to-consume” images, with the same frantic speed with which canned soup or a Coca-Cola is consumed. The first series of Campbell’s soup dates back to 1962: the installation consists of thirty-two identical paintings of the same size. The style of the painting is basically an identical sequence of a form that is repeated thirty-two times. The use of color is important in understanding the meaning of the work: the Campbell’s soup boxes are printed on a white background that highlights the object and makes it an absolute icon of modernity. The artist created monumental images that became part of people’s everyday life, in this case supermarket products, as well as Brillo boxes (1964-68), turning them into icons of American life. In his works Andy minimized emotional participation.

True to the function of “recorder,” Warhol treated the image of Jacqueline Kennedy, wife of John Kennedy, with the same coldness. The assassination of the U.S. president also took on a symbolic dimension through the figure of the first lady, Jacqueline, whose images from the moment of the assassination attempt went around the world. Warhol once again recorded the mood of the society in which she lived, and transformed Jackie into a new icon. The artist worked specifically on two images, one prior to the assassination attempt Jackie III (1966), and the other following Lavender Jackie (1966), in this way documenting a before and after event, whose grief did not touch only the Kennedy widow, but reached the entire country. The artist merely chose and exalted the images he deemed relevant because, regardless of their ideological or ideal implications, they accompanied and thus influenced everyone’s life. The same approach was reserved for the mythical figure of Mao Tse-Tung. In this case the arist chose the customary image of the “Great Helmsman,” the one published on the cover of the Little Red Book (an anthology of quotations from his writings and speeches), and repeated it countless times. The uniqueness of this image was that the ultimate representative of a communist empire like China became a widespread icon in a country as symbolic of capitalism as the United States.

Having become a myth himself, Warhol constructed his own icon in the same way he would construct a portrait. Beginning with a photo by photographer Malcolm Kirk (this is the 1967 silkscreen Self-portrait ), the American artist poses three-quarter-length, gazing into the camera with a beleaguered expression, his hand resting on his chin, his index and middle fingers over his mouth. Reinforcing the enigmatic mark of the image was the use of the silkscreen technique, which allowed the artist to leave half of the face in shadow and make it almost invisible. Andy did not return to the practice of self-portraiture until the late 1970s, a period when graphics appeared in which the artist’s face doubles and triples as in Self-portrait (1977). The constant reflection on self and image landed in 1981 when the artist made The Shadows (1981), the summa of all his work on self-representation. The series of preparatory Polaroids shows how attentive the artist was to the construction of the work, moreover, the title itself highlights the fact that the center of interest for Warhol is the shadow and not the body that creates it. The practice of emotional detachment andimpersonality represented a fundamental part of Warhol’s poetics: however, it is equally true that the subjects were never chosen randomly and induce different reactions in the viewer. Compositions such as Most wanted man no.1, Jhon M. (1964), Elecrtic Chair (1971), and Knives (1981), represented the dark side of that same society that produces consumer goods and the money to buy them. Above all, they occupied within the mass media the same space as the stars of film and politics and overlapped with them, blended in without any differentiation. The famous “fifteen minutes of fame” can touch even the most wanted murderer in America, or the unfortunate and anonymous protagonist of a car accident.

Sometimes it can happen that the album cover becomes more famous than the songs on it: This was precisely the case with the album cover that Andy Warhol designed for the band The Velvet Underground, for which he also became a producer. In 1966 Lou Reed founded The Velvet Underground and the group was incorporated into the Factory of the father of Pop Art, who financed their first album, allowing the group to establish itself in the New York music scene as one of the most innovative. The yellow fruit on the cover of the Velvet Underground’s debut album became iconic. The artist-designed fruit, which in early editions could be “peeled,” making bananas appear pink, appeared as a clear provocation on the artist’s part. The album that came out in 1967 soon became a cult object among vinyl and art collectors and today is worth about two thousand dollars. Photography was the basis of Andy Warhol’s painting ; in fact, most of his works grew out of them, some done directly by him others taken from newspapers and then reworked. Other photos, on the other hand, remained as such and became a kind of record of his social life, his encounters with celebrities and everyday life in its countless aspects. Some of the most famous Polaroids include the one portraying the artist Joseph Beuys (1979), or Self-portrait with John Lennon and Yoko Ono (1971). Then there was a work that encapsulated all the myths: it was Myths (1981), which at first glance might have seemed a rather extravagant painting. On the far right, in the tenth frame, we find Andy Warhol staring fixedly to the left. He is the only real person among the nine myths, which according to the artist are the Wicked Witch of the West from The Wizard of Oz¸ Dracula, the Mami in the film Gone with the Wind, Greta Garbo, Santa Claus, Superman and others. Although these myths appear only in television, movies, or comic books, the American artist recognized that they played an important role people’s lives, and for him to appear alongside these myths was not a strange thing. Finally, Self-portraits (1986), was the last version of portraits the artist created before his death and was defined as one of the most iconic.

Warhol also made an important contribution to film, the productions of which took place in the Factory itself. Empire (1965) presents one of New York’s most famous skyscrapers theEmpire State Bulding in confrontation with the cloud-filled sky. The film lasts eight hours, from dusk to dawn, the still image of the building is offered continuously and the viewer cannot help but “wish” for the smallest change to happen. Chelsea Girl (1966) lasts more than three hours: two films are projected on the screen at the same time. All experiences and languages alternate: color and black and white, silent and sound, stasis and unbridled dynamism. The film has no real formal narrative, but rather presents the various residents of New York’s Chelsea Hotel in 1966: a drug addict arguing with himself rather than with others, two lesbian girls in bed, a girl on LSD, a group of homosexuals, etc. By choosing film, it is as if Warhol chose a new tool to free himself from rules and laws.

|

| Andy Warhol, Untitled (Mao) (1972; silkscreen on paper, 91.44 x 91.44 cm; Milan, Collection Teresa and Michele Bonuomo) |

|

| Andy Warhol, Flowers (1964; lithograph edition of 300 copies, 55.8 x 55.7 cm; New York, MoMA) |

|

| Andy Warhol, Hammer and sickle (1977; painting and ssynthetic polymers and silkscreen on canvas, 182.9 x 218.4 cm; Rome, National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art) |

In 1993, a museum dedicated entirely to Andy Warhol was built in his hometown of Pittsburgh. The museum houses the largest collection of the American artist’s artwork and archival materials. Paintings, drawings, commercial illustrations and photographs cover the full range of Warhol’s career, from his early work as a student to his Pop Art paintings. Staying still overseas at MoMa (Museum of Modern Art) it is possible to see some of his most famous works such as Flowers (1964) and Marylin Monroe (1967). At the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York are the 1986 self-portraits Electric Chairs (1964) and Orange Disaster (1963). In contrast, other works such as Skulls (1976), Liz Taylor (1965) or Gun (1981) are at the Tate Modern in London.

Works by Andy Warhol can be found in various museums around the world, including Italy.The seriality with which the artist created his works has led to a great diffusion of multiples, which are moreover often the subject of major exhibitions and can also often be seen at modern art fairs.

|

| Andy Warhol: life and major works of the father of Pop Art |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.