Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal; Venice, 1697 - 1768) was one of the most celebrated painters of vedute of his time, among the greatest of vedutismo, the genre born in the eighteenth century that focused on extremely accurate and realistic landscapes and views. In his vedute, the artist crystallized the wonderful lagoon city and its inhabitants, sometimes idealizing it but never running into the unreal. His achievements in the fields of perspective and atmospheric rendering led him to such innovative artistic results that they made him the most sought-after painter of the time.

The poles of his existence were Venice and England (in England Canaletto remained for a full nine years). However, although the Venetian and English landscapes were very different, the painter’s stylistic signature remained the same. Canaletto was not only famous for his talent, but he also had a reputation for being exorbitant; in fact, his works were very expensive and his character was rather grumpy, as many of his clients complained. Nevertheless, there were many significant patrons, including the Prince of Liechtenstein and the banker and future English consul in Venice Joseph Smith, who opened the painter’s doors to wealthy English collecting. Canaletto was skilled in the use of perspective and especially color, modeled according to light gradations that infused the painting with an idyllic atmosphere.

|

| Canaletto |

Giovanni Antonio Canal was born in Venice in 1697, probably on October 17 or 18, to the painter Bernardo Cesare Canal and Artemisia Barbieri. It was the father figure who transmitted the painterly sensibility to his son Giovanni, with whom in fact he collaborated in the staging of some melodramatic performances by preparing the painted backdrops. Of Antonio’s theatrical activity, however, no graphic or pictorial evidence remains. It is probable that, even within the framework of scenographic interests, he began to practice painting of "views from nature," under the suggestion of the landscape painter Marco Ricci. In 1719 he went to Rome with his father. The Roman sojourn became pivotal for the young Canaletto (a nickname given to him to distinguish him from his father), who matured and finally decided to devote himself to landscape painting. Fascinated by the Roman ruins, the painter abandoned his theatrical activity.

A document from 1720 attests to Canaletto’s return to Venice, as his name appears among those of the "painters of the fraglia,“ a term that in the territories of the Venetian Republic indicated the guilds of arts and crafts. In 1722 Canaletto was found to be engaged in the execution of perspectives and landscapes in a ”capriccio" depicting Lord Somers’ Tomb. “Capriccios,” in the artistic sphere, are understood to be all those works that are the result of the artist’s creativity: according to Filippo Baldinucci, "a capriccio is a work of art that arises from a sudden imagination of the painter. " These works were commissioned from Canaletto by Owen McSwiney, an Irishman who first became involved in the theater as an impresario, but did not reap great fortunes, and was later engaged by Lord March in the ambitious project of having the most celebrated Italian painters execute a series of allegorical tombs of the most illustrious figures in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century English history. Canaletto’s name appears in a letter sent by McSwiney to Lord March. Canaletto’s growing fortune was evidenced by a number of significant works, which are now part of the Liechtenstein collections: The Grand Canal to the Rialto Bridge, St. Mark ’s Square, which was one of the earliest depictions of the square and the painter’s favorite subject, and the Beggars’ Ward. In 1725 a collector from Lucca, Stefano Conti, commissioned works from the Venetian painter depicting the Grand Canal and the Rialto Bridge, both dated 1725, which are now part of a private collection. It is very likely that by this time Canaletto had attracted some interest from the English banker, merchant, and collector Joseph Smith, a figure who played a key role in the Venetian painter’s artistic fortunes. The relationship between Smith and Canaletto was not immediately particularly serene: however, as early as 1730 the painter turned out to be engaged in producing works for the banker, destined for British collectors. Testifying to Canaletto’s success was the public recognition he received in 1733 as “best painter of views.”

The 1930s were very busy for the painter, who was commissioned many works, mostly by English patrons such as the Duke of Bedford, the Duke of Buckingham, and the Prince of Liechtenstein . In 1740 the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) broke out, which deprived Canaletto of the English travelers who were his main patrons: however, Joseph Smith entrusted the painter with five views of Rome and some capriccios. Some scholars speculate about a second Roman journey, although there are no documents to testify to this: therefore, it is more likely that the views commissioned by Smith were taken from his youthful drawings. George Vertue, English engraver, antiquarian, and art historian notes in his Notebooks Canaletto’s arrival in London in late May 1746. The London celebrity Canaletto enjoyed was so vast that he immediately received many commissions from art collectors as well as English politicians. He depicted many views of the Thames, not unlike the Grand Canal in Venice, but also London architecture and landscapes. The English sojourn ended in 1755, the date of his final return to La Serenissima. In the years to follow the painter’s works would diminish and his attention turned more to “architectural whimsy,” although, at times, he always sat in St. Mark’s Square intent on sketching and studying the marvelous landscape the Serenissima offered. In 1763 he was elected a member of the Venice Academy of Art, and on April 19, 1768, he died in his hometown.

|

| Bernardo Canal and Canaletto, Santa Maria Aracoeli and the Campidoglio (c. 1720; oil on canvas, 146.5 x 200 cm; Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts) |

|

| Canaletto, Piazza San Marco towards the Basilica (c. 1723; oil on canvas, 141.5 x 204.5 cm; Madrid, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza) |

|

| Canaletto, Grand Canal from Campo San Vio near the Rialto Bridge (1723; oil on canvas, 144 x 207 cm; Venice, Ca’ Rezzonico, Museo del Settecento Veneziano) |

|

| Canaletto, The return of the bucintoro to the pier on the day of the ascension (c. 1729; oil on canvas, 120.5 x 151 cm; Turin, Pinacoteca Giovanni and Marella Agnelli) |

|

| Canaletto, The Entrance to the Grand Canal with the Customs House and the Salute Church (c. 1730; oil on canvas, 49.6 x 73.6 cm; Houston, Museum of Fine Arts) |

The eighteenth century was a century of profound transformation: rationalism, optimism and faith in man were the basis of the eighteenth-century spirit. In painting, too, there was a strong need for objectivity and precision aimed at giving "vedutismo" also a certain documentary capacity. Canaletto was one of the best interpreters of this artistic season: his particular attention to atmospheric rendering and scientific research of reality made the painter one of the most appreciated abroad and in northern Italy. It was during his trip to Rome with his father that Canaletto came to vedutismo, abandoning theatrical set designs. In the work Santa Maria Aracoeli and the Campidoglio (1720) the Basilica of Santa Maria in Aracoeli stands out on the left while the Campidoglio is on the right. The minute figures make the architecture even more majestic. It is most likely that the canvas was painted by Canaletto after his return to Venice. One of Canaletto’s most famous Venetian foreshortenings is Piazza San Marco (1723) in which the painter resumed the traditional perspective setting with a vanishing point on a central axis. The center of the painting is dominated by the beautiful St. Mark’s Basilica, preceded by the Procuratie, the Old Basilica on the left and the New Basilica on the right. In the background behind the basilica peeps a small part of the Doge’s Palace. The attention to detail is visible both in the architecture, depicted in all its details, but also in the realistic way the sky is drawn. The artist enhanced the chiaroscuro contrasts and played on the effects of light and shadow, given by the ability to tune the green-blue and gray-silver color range. By the same is Canal Grande from Campo San Vio near the Rialto Bridge (1723), in which the canal is directed toward the vanishing point of the canvas and is punctuated by the buildings that run along its sides. The work perfectly expresses the meticulous attention paid to light, which in fact illuminates the buildings on the left revealing their decay.

The Return of the Buccintoro to the Pier on Ascension Day (c. 1729) was a work made for the banker Joseph Smith and depicts the celebrations on Ascension Day to mark Venice’s marriage to the sea. The work is striking for its rich composition and attention hai detail. The bucintoro, or the golden galley of the Doge of Venice, has just arrived at St. Mark’s Square, sumptuous vessels of nobles follow and surround it. The Doge’s Palace shines from the light coming from the right and illuminating the marvelous Venetian-Gothic facade. The small figures that populate the space restore liveliness and dynamism to the canvas. Canaletto always painted the same subjects but with different points of view as in the case of The Entrance to the Grand Canal with the Customs House and the Salute Church (c. 1730), of which several variants were painted. In the one preserved at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, once again the buildings are presented in their majesty, and immediately recognizable on the left is the church of Santa Maria della Salute, whose staircase leads the Venetian senators inside the building. The center of the picture is teeming with figures on top of the boats, who are depicted in their everyday lives. A different atmosphere emanates from the work The Stonemason’s Courtyard (1727-1728): the canvas depicts a glimpse of everyday life, which is why some art historians argue that the work was commissioned not by an Englishman but by a local client. In the background, slightly shifted to the left is depicted the church of Santa Maria della Carità, which was later annexed to the Accademia Gallery . The canvas captures moments of everyday life: on the right, near the wooden building, a woman approaches the well in the shape of a capital, which can still be seen today; on the left a sympathetic and colorful scene shows a woman rescuing a child who has fallen to the ground; in the center, on the other hand, we see two stonemasons concentrating on their tasks.

One of Canaletto’s most interesting works is Il bacino di San Marco vero est, a work that is generally dated between 1735 and 1740. It is well known that in order to paint canvases such as these, Canaletto resorted to the camera ottica, which was an instrument often used by 18th-century painters that allowed them to project the image of reality onto a screen of greaseproof paper, after which the artists proceeded to tracing. In this work, Canaletto, through the use of the camera ottica managed to make the view of the landscape objective. The result was that of an extremely wide and monumental view. Once again Canaletto surprises with his ability to depict details and his scientific attitude to the subject.

St. Mark’s Basin with the Customs House from the Punta della Giudecca is one of the artist’s early works. This foreshortening was one of the most evocative of the lagoon city and the one most requested by the patrons. The diagonal of the street in the foreground leads the viewer’s gaze to the right, and the noble couple walking accentuates this perspective. In the foreground a small white dog searches for food. The animal is testimony here to the realism to which Canaletto tended, but the couple walking is also a good example, in fact their clothes were made to the smallest detail.

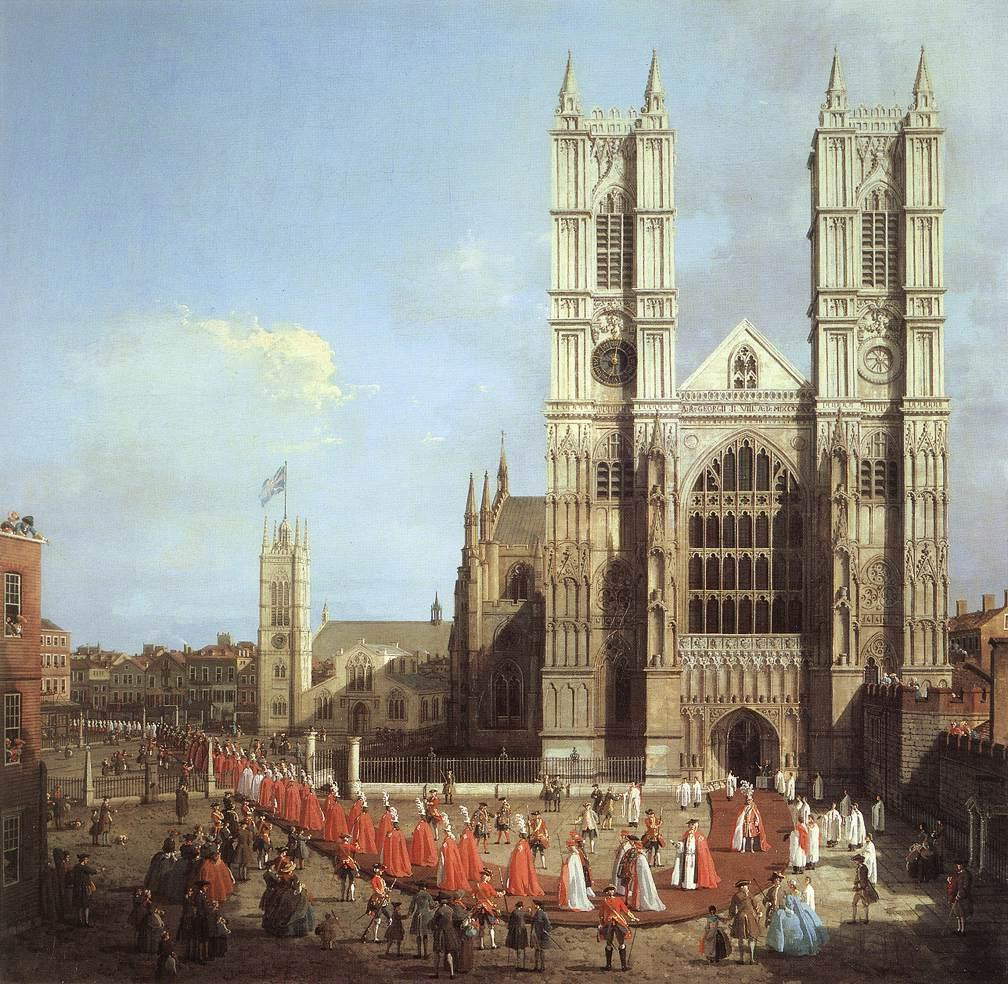

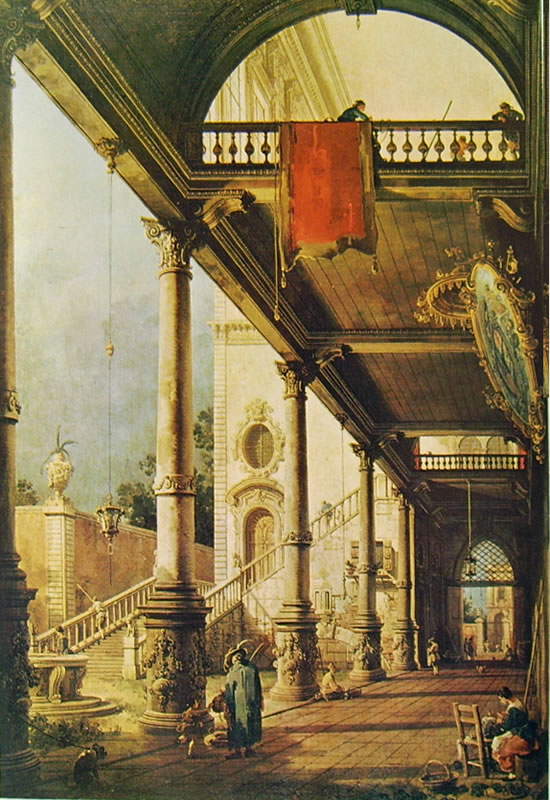

In 1746 Canaletto moved to London, and there were many patrons during this period, although his art began to take on more mechanical and mannered features. Figures became more conventional and the play of light and shadow were reduced to whitish brushstrokes. The English landscapes are calm and devoid of complex architecture like the Venetian ones. Unfortunately, many of these works are part of private collections, so they are not accessible to the general public; however, we recall here the most famous canvases from the English sojourn. Westminster Abbey with the procession of the Order of the Bath can be dated to 1749. It is a painting for celebratory purposes commissioned by the Dean of Westminster after the installation of the Knights of the Order of the Bath in Henry VII’s chapel in the abbey. The canvas is dominated by the majestic abbey with its two Gothic-style bell towers. In the lower part of the painting, teeming with figures, the religious ceremony takes place. Politician Thomas Hollis was of Canaletto’s most important patrons of the English period. For him the painter painted The Walton Bridge and The Interior of the Ranelagh Rotunda, in the latter, on the verso, appears the inscription “done in the year 1754 in London for the first and last time with every greater at the instance of Mr. Cavalier Hollins my esteem.” So the date and patron are certain. For Mr. Hollis, Canaletto had to make other works as well, including some Roman views. The painting shows the interior of the famous rotunda, demolished in 1805, at Renelagh Gardens in Chelsea. On the right an orchestra is playing, attracting the attention of the crowd below. The elegant, petite figures at the bottom emphasize the building’s height even more. The lighting comes from the upper left corner, highlighting the glow of the upper part of the rotunda, naturalistic decorations, arches and windows. Also from the English period is the canvas Eton College 1755: the viewpoint is from the bank of the River Thames toward Eton College, which is set on an expansive lawn. The landscape is softly lit and on the riverbank people are enjoying the sunny summer day, some having a family picnic while others are fishing or on the boat. In all likelihood the work was made based on an earlier sketch, as there are some architectural discrepancies. After his return to Venice, the painter continued his artistic quest by painting the most beautiful and evocative places of the Serenissima. He also devoted much time to architectural capriccios: that is, compositions in which the artist paints various buildings without reference to a particular place, so they are works of pure fantasy. An example is Capriccio con colonnato e cortile (1765) in which it is the architectures and their decorations that take center stage, although scenes of everyday life and figures are not sacrificed. Canaletto always had many patrons both in Venice and abroad. His technique, imagination, and ability to crystallize landscapes according to reality but with a slightly idyllic tone made him one of the established painters of the 18th century.

|

| Canaletto, The Stonemason’s Courtyard (1727-1728; oil on canvas, 123.8 x 162.9 cm; London, National Gallery) |

|

| Canaletto, The Basin of St. Mark’s True East (c. 1735-1740; oil on canvas, 125 x 204 cm; Boston, Museum of Fine Arts) |

|

| Canaletto, Westminster Abbey with the procession of the Order of the Bath (1749; oil on canvas, 101.6 x 101.6 cm; London, Westminster Abbey) |

|

| Canaletto, The Interior of the Ranelagh Rotunda (1754; oil on canvas, 51 x 76 cm; London, National Gallery) |

|

| Canaletto, Capriccio with Colonnade and Courtyard (1765; oil on canvas, 131 x 93 cm; Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia) |

Three capriccios, including Capriccio con colonnato e cortile (1765) are kept at the Accademia Gallery in Venice. Also in Venice at the Museo del Settecento Veneziano in the Ca’Rezzonico palace, one of the city’s most famous, are Il grande Canale verso Rialto (1723) and Rio dei Mendicanti (1723). At the Accademia di Carrara in Bergamo is Il canal grande (1730). In Rome, at the National Gallery of Ancient Art are Il Canal Grande from the Rialto Bridge toward Ca’Foscari and La piazzetta (1733-1735). The Royal Collection in Windsor has Regatta on the Grand Canal (1732) and Interior of St. Mark’s at Night (1733). Staying still in the British area, the National Gallery in London has many of the artist’s works, including Cortile dello Scalpellino (1725), The Doge at the Feast of San Rocco (1735), The Grand Canal to the Southwest (1738), and the beautiful Renelagh Rotunda (1754).

|

| Canaletto, life and works of the great master of Venetian vedutism |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.