Frida Kahlo (Coyoacán, 1907 - 1954) was one of the most important artists in 20th-century Mexican art. She and her husband Diego Rivera (Guanajuato, 1986 - Mexico City, 1957) formed one of the most emblematic couples of the twentieth century: their love affair was as passionate as it was tormented and unfaithful. At only eighteen years old, Kahlo, was the victim of a terrible accident that caused her spine, ribs and foot to fracture, and over the course of her life she underwent some thirty-two surgeries in hopes of reducing her pain. However, despite her weak health, Frida Kahlo was described by those who got to know her as a very passionate, independent, and rebellious woman: as a teenager she loved to dress like soldaderas (women who fought during the Mexican Revolution), joined the Communist Party, and had numerous lovers, both men and women.

Her canvases were greatly appreciated by both Diego Rivera, but also by the Surrealist poet André Breton and artists such as Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró, Vasilij Kandinsky and many others who recognized her talent. She was considered by many to be an artist who could be ascribed to the current of Surrealism, but Frida never accepted being labeled under this category. Her painting, although there were characteristics common to the Surrealist movement, was always original and autonomous, and this allowed her to become one of Mexico’s most important artists.

Although she is considered a naïve artist in that she painted without having had any traditional training (she learned some rudiments from an engraver, Fernando Fernández, a family friend, and had no other masters) and guided solely by her feeling, her art deals with a breadth of themes (from self-representation to issues of gender, from identity to postcolonialism) with an approach that mixes the fantastic and the real (in ways akin to those of surrealism and magic realism and with the immediacy of muralism), that has brought her to international levels of attention, to some extent facilitated in part by her biographical story.

|

| Frida Kahlo |

Frida Kahlo was born on July 6, 1907 (her full name is Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón) in Coyoacán, a suburb of Mexico City. Frida’s father, Guillermo Kahlo Kaufmann (born Carl Wilhelm Kahlo), was a German photographer who emigrated to Mexico in 1891. Her mother, Matilde Calderón y González, on the other hand, was a wealthy Mexican woman of Spanish descent. The couple had four children, but Frida was the more rebellious and passionate one, showing an independent and strong nature. Feeling herself a child of the Mexican Revolution, she said for a long time that she was born in 1910, the year the revolution began. At only thirteen years old she was a militant member of the Communist Youth, and in her high school years she was part of a group of boys who supported socialist-nationalist ideas. During this period Frida loved to dress like soldaderas , that is, like the legendary women who fought on the front lines during the Mexican Revolution.

She first met her future husband Diego Rivera in 1922 at the Simón Bolívar amphitheater in Mexico City (opened in 1910), while the painter was painting the first mural of his artistic career, The Creation. Rivera and Frida married seven years later, in 1929, unaware that they were about to become one of the most emblematic couples of the 20th century.

In 1925 a traumatic episode occurred: Frida, while returning from school by bus, was involved in a terrible accident. She suffered very serious injuries to her back, legs and shoulder, and the period of infirmity was a long and silent torture for her. During this period of convalescence, her parents gave her brushes and canvases to help her pass her time better, so Frida began to paint and develop an artistic language influenced by her loneliness. She used herself as a model: her own body, her wounds and her emotions. During this period she made a self-portrait, the first in a long series(read more about Frida Kahlo’s self-portraits here), which she gave as a gift to Alejandro, her boyfriend at the time. Thanks to the letters the young painter sent to her boyfriend, it is possible to realize the melancholy and despair by which she was afflicted. Little by little, a slow recovery began for Frida that allowed her to regain her former cheerfulness: she began to seek employment, continued to cultivate her passion for art and became involved in the communist struggle. Toward the end of the 1920s, Frida met photographer Tina Mod otti(read more about Tina Modotti’s art here), with whom she established a close friendship.

During a dinner at her friend’s home, Frida saw Diego Rivera again, who had returned to Mexico after many years in Europe. The two began and dated, and in 1929 they were married at the town hall in Coyoacán, despite the fact that Frida was aware of the constant betrayals she would face. The young couple took a house in the center of Mexico City, which soon became a mandatory destination for artists, intellectuals, poets and revolutionaries. In 1930 they moved to the United States, where Rivera was invited to paint the wall inside New York’s Rockefeller Center and some frescoes in San Francisco. During her U.S. sojourn Frida became pregnant, but because of the accident she was never able to carry the pregnancy to term. She never had any children, and this was one of her greatest sorrows, also expressed several times in her works. Frida had many lovers, both men and women, including Russian revolutionary Lev Trockij, who was granted political asylum in Mexico in 1929. The Frida-Rivera couple could thus be considered “open,” although in reality Frida suffered greatly from her husband’s constant betrayals, especially when she discovered that Rivera cheated on her with her younger sister, Cristina.

In 1937 the Surrealist poet and intellectual André Breton arrived in Mexico to meet Trockij and to give a lecture series on the new Surrealist movement. Breton immediately appreciated the Mexican painter’s canvases, calling her a “surrealist,” and suggested that she hold a solo exhibition in Paris. The exhibition only really took place thanks to the decisive intervention of Marcel Duchamp, and although, it was not particularly commercially successful, Frida gained recognition from the likes of Pablo Picasso, Vasily Kandinsky, Joan Miró, and Yves Tanguy. In 1939 Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo divorced, but political events intersected with the couple’s private life, so the two married again the following year. On this second marriage pact Frida imposed two constraints: the artist would provide for her own support and she would no longer have sexual relations with her husband. Frida’s last decade was characterized by an increasing deterioration of her health and she was forced to wear painful orthopedic braces. Physical suffering was also accompanied by the full public affirmation of her work as a painter, which resulted in many international exhibitions. In 1950 the artist underwent a seven-month hospitalization in which she was operated on seven times, without, however, incisive improvement. In 1953 Mexico paid tribute to its greatest artist with a solo exhibition in the capital, realizing that she would not live much longer. After her right leg was amputated in 1953, Frida attempted suicide several times, hoping to put an end to all the torture and pain that accompanied her throughout her life. Death came on July 13, 1954 as a result of a pulmonary embolism that was neglected.

|

| Frida Kahlo, Henry Ford Hospital (The Flying Bed) (1932; oil on canvas, 38 x 30.5 cm; Mexico City, Museo Dolores Olmedo) |

|

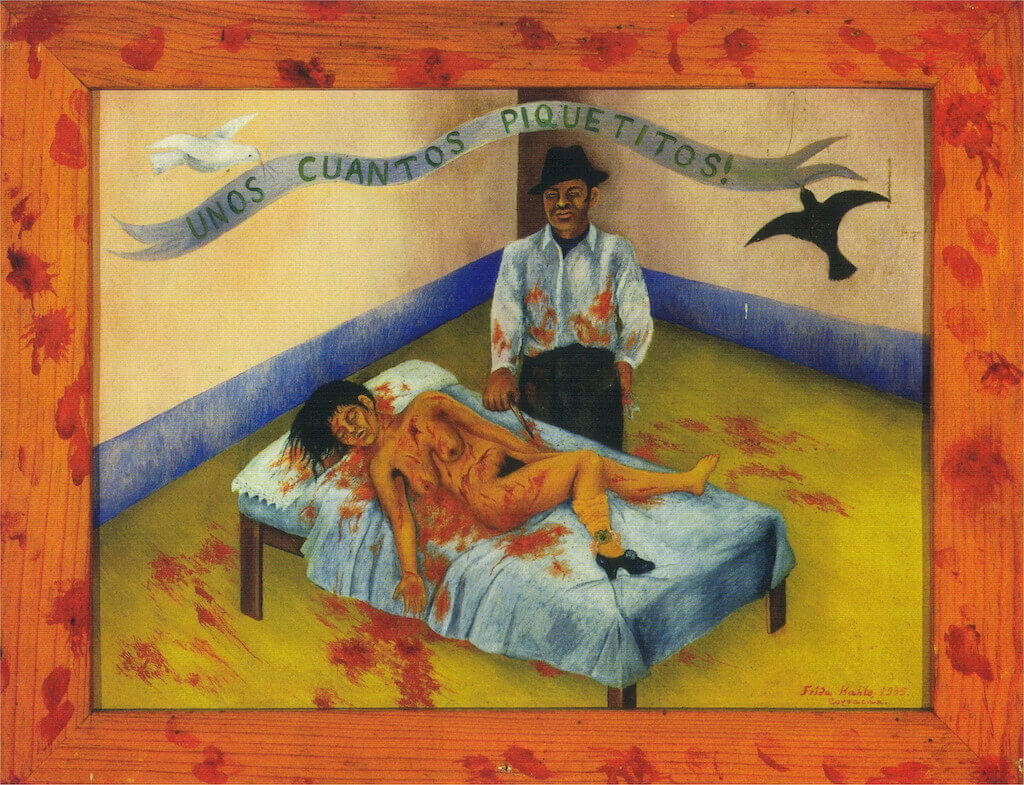

| Frida Kahlo, A Few Dagger Blows (1935; oil on metal, 48.5 x 38 cm; Mexico City, Museo Dolores Olmedo) |

|

| Frida Kahlo, My Grandparents, My Parents and Me (1936; oil and tempera on metal, 30 x 34 cm; New York, MoMA) |

|

| Frida Kahlo, The Two Fridas (1939; oil on canvas, 173.5 x 173 cm; Mexico City, Museo de Arte Moderno) |

Frida Kahlo’s artistic path was entirely original and independent. Her works were far from both Mexican muralism and surrealism, but at the same time borrowed some aspects from these currents (such as, for example, an interest in strong, bright colors and references to dreamlike images). Kahlo executed many self-portraits that depicted her state of physical and mental suffering. The key aspects of her works were: a focus on the female body, untethered from the stereotypical, macho view, and the ability to express Mexico’s cultural identity.

In the work Henry Ford Hospital (The Turning Bed) (1932), Frida is lying on a hospital bed with blood-stained sheets. The objects chosen allude to a dramatic event that marked Frida at that time: namely, the miscarriage that occurred in Detroit during one of Frida and Rivera’s stays in the United States. From the woman’s belly depart six threads that lead to objects of strong symbolic value. The lower part of the painting depicts the bones of a pelvis, a wilted orchid that Rivera gave his wife as a gift during her surgery, and a surgical machine that can easily be traced back to the operation she had just undergone. At the top, however, the three filaments lead to a snail, which alludes to the female cycle or conception, a fetus, and an anatomical model of the female reproductive system. All these symbols are set in a gray, inhospitable landscape with Detroit skyscrapers in the background.

Another work related to his personal life is A Few Shots of a Dagger (1935). The work was inspired by a newspaper article that shocked her, making a terrifying crime story a figurative motif. The article recounted that a man for reasons of jealousy broke into the room of the beloved woman, striking her with numerous stab wounds. When the man was tried he declared that “it was only a few stab wounds.” This was also the time when the painter discovered that Rivera began a romantic relationship with Frida’s sister, Cristina, and although the painter was aware of her husband’s usual infidelity, the fact that this time the betrayal took place with her sister added a painful and humiliating feature. It is then possible to glimpse in the naked and ravaged body of the woman, dressed only in a stocking and a shoe, the body of Frida, while in the face of the man, near the corpse holding a knife, it is easy to recognize some somatic features of Diego Rivera.

The theme of genealogy and self-recognition was addressed by Kahlo in 1936 with the work My Grandparents, My Parents and Me. The painting centrally depicts little Frida at the age of about three, standing in the center of the patio of the family home, destined to become the famous Casa Azul. With her right hand, the child holds ribbons that flow into the images of her maternal and paternal grandparents, while her parents pose in the center. The theme of descent and identity was a major issue for the artist, probably also because of her inability to have children. This impossibility weighed heavily on the artist, who carried with him the guilt and burden of being among the last of his family. In 1939 after traveling to Paris and divorcing her husband Rivera, Frida returned to live in the family home, Casa Azul.

During this period the artist made many self-portraits, including the famous masterpiece The Two Fridas (1939). The canvas depicts two Fridas sitting on a bench and almost identical, both in hairstyle and pose but wearing very different clothes. The Frida on the right wears European clothes, while the one on the left wears traditional Mexican clothes. The two women are united by a handshake and especially by a vein connecting the two hearts. The Frida in traditional dress has her heart resting on her shirt, thus totally exposed, especially to love. In her hand she holds a cameo depicting the image of her husband Diego Rivera. On the other hand, on the other hand, the European Frida has her heart protected in her rib cage and with her hand she holds a scissor with which she cuts the vein that feeds the heart. It is clear then the strong symbolic value of this painting: Frida wants to be reborn through a deep cut with the sentimental past and yearning for a new life. The work became for the artist the compensation of a deep pain.

Another work closely related to the divorce with her husband was Self-Portrait with Necklace of Thorns (1940). In the canvas, Frida depicted herself in a perfectly frontal and motionless manner, recalling some medieval icons or some works by Piero della Francesca because of the geometry of the almost perfect face. The almost sacred character surrounding the painting is necessary for a description of herself as a martyr: Frida, in fact, has a kind of crown of thorns on her neck. On her shoulders rest a monkey, alluding to family affections, and a cat with menacing eyes to remind us of the artist’s vitality and sensuality. The work is undoubtedly a self-representation of a wounded and offended woman.

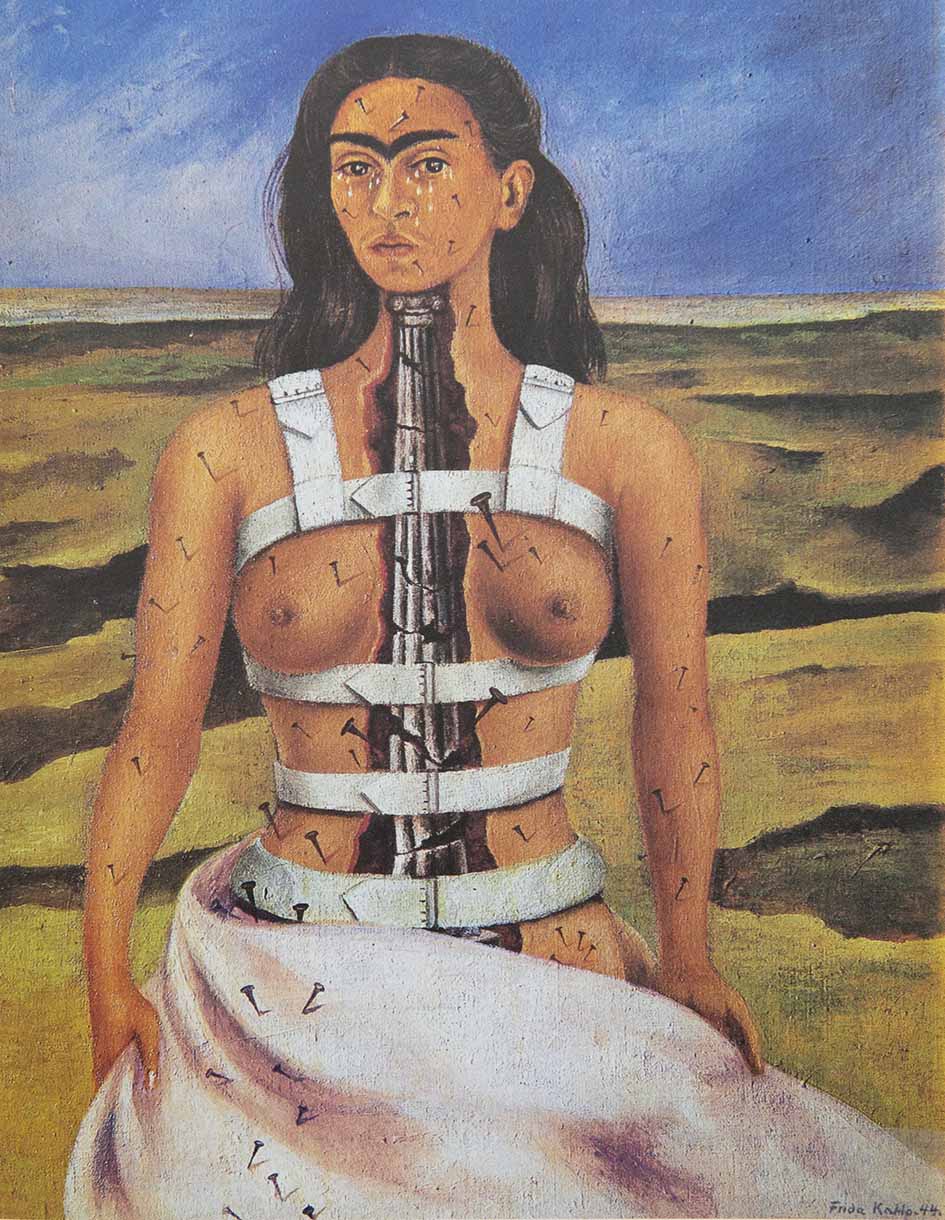

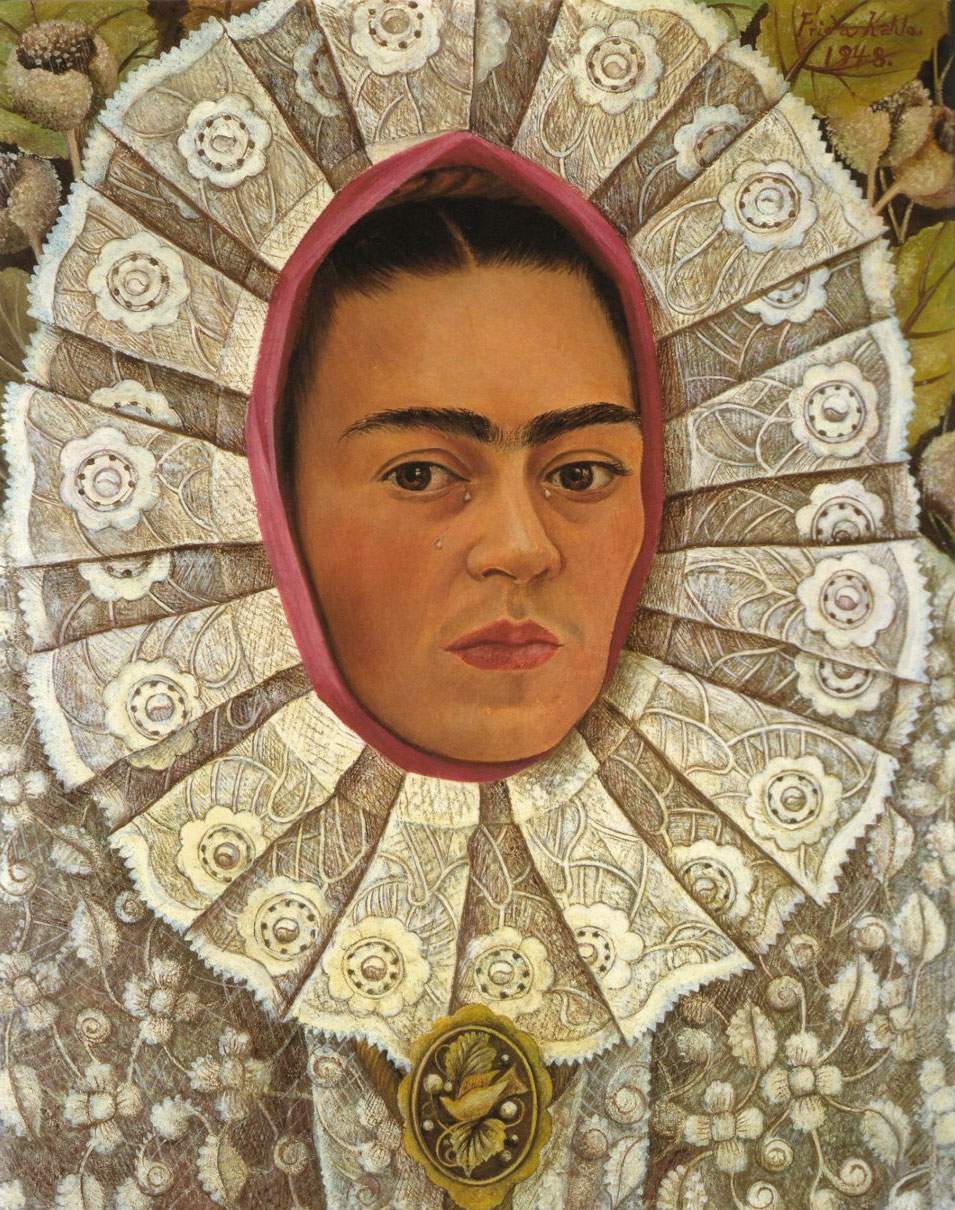

The Broken Column (1944) was born to show, presumably, her own martyrdom. Here the artist portrayed herself weeping, naked with her body pierced by nails. In the center of the body, the ribcage opens up revealing an Ionic column, damaged by visible cracks. Just as the architectural column must be intact to support the building, similarly Frida’s spine, damaged by the car accident, cannot support and sustain her posture. Also underscoring this sense of malaise and pain is the inhospitable landscape in the background. In 1946 Frida underwent back surgery. The painter hoped that after the operation the pain would pass but it did not: the pains resumed as before and the artist fell into depression. Evidence of this deep malaise is the work The Wounded Deer (1946) in which Frida painted a deer with its face and wounded by hunters’ arrows. The torture of the arrows alludes to the pains Frida had to endure even after her last surgery that did not go as she hoped, but the wounded deer-woman cannot help but refer back to the martyrdom of St. Sebastian. In the background a cloudy but vaguely sunny sky hints at a faint hope for a better future. In Self-Portrait (1948), Frida painted herself with her face completely surrounded by the scenic folds and exuberant decorations of headgear typical of the territory of Tehuantepec, in the state of Oaxaca. The tear-streaked face indicates the physical suffering that tormented Frida. The flowers in the background have been interpreted as an allusion to fertility and Frida’s failure to have children. This interpretation lends an additional melancholic character to the work. In her works one can perceive the almost obsessive relationship with her tortured body, and the strong interest in defending the culture and tradition of her people through her art.

|

| Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Necklace of Thorns and Hummingbirds (1940; oil on metal foil, 63.5 x 49.5 cm; Austin, Harry Ranson Center) |

|

| Frida Kahlo, The Wounded Deer (1946; oil on masonite, 22.4 x 30 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Frida Kahlo, The Broken Column (1944; oil on canvas pasted on masonite, 30.5 x 40 cm; Mexico City, Museo Dolores Olmedo) |

|

| Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait (1948; oil on masonite, 50 x 39.5 cm; Mexico City, Samuel Fastlicht Collection) |

To fully understand the life and works of Frida Kahlo you can visit the Frida Kahlo Museum in Mexico City. The museum originated in the Casa Azul, or the artist’s family home, houses several works (although mostly minor works) and also makes it possible to get a sense of Diego Rivera’s artistic activity and the letters he exchanged with Frida.

Another relevant nucleus of works by Frida Kahlo is that of the Dolores Olmedo Museum, which was created thanks to the collecting activities of Dolore Olmedo, a Mexican businesswoman, who collected as many as 25 works by Frida Kahlo. Staying still in Mexico at the Museo de Arte Moderno is the artist’s masterpiece, The Two Fridas (1946). In the United States, on the other hand, the MoMa, which houses key works in Frida Kahlo’s artistic activity, is not to be missed.

|

| Frida Kahlo. Life and works among naïve art, surrealism, and muralism |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.