“He remoulded the art of painting from Greek into Latin”: this is how Cennino Cennini wrote about the art of Giotto di Bondone (Florence?, c. 1267 - Florence, 1337), emphasizing its great importance. Giotto in fact abandoned the hieraticity and solemnity of earlier, Byzantine-style painting in favor of an art that was more natural and more faithful to reality. Giotto is one of the most famous painters in the history of art, there are many legends and anecdotes about him: yet, of such an important painter we do not even know his real name. Perhaps Biagio or Ambrogio, he came from a family originally from the Mugello hills and was a pupil of Cimabue, another great artist of the time.

With Giotto, the history of Western art finds the first figure of a painter surrounded by an almost mythical aura. Everyone is familiar with the legends attributed to this extraordinary artist, beginning with the famous anecdote that Giotto was able to draw a perfect circle freehand, and yet another very famous anecdote is that his talent was noticed by Cimabue when Giotto was still a child, specifically on a day when while grazing sheep he delighted in drawing them on rocks to fool the time. Legend has it that he drew these sheep with such skill that Cimabue, who was on his way from Florence to Bologna, took the young man under his protection to teach him the art. The tale is very poetic but, of course, it need not be given credence: of course, the young Giotto followed a (not known, but nevertheless plausible) procedure similar to that of so many other painters in the history of art, that is, he would have been entrusted by his family to the workshop of an artist. In Giotto’s case, his father Bondone probably, after noticing his qualities, decided to send him to the workshop of a painter in Florence, perhaps Cimabue himself: we are not sure because there are no documents that can testify to an apprenticeship of Giotto to Cimabue, so art historians can only make deductions on the basis of style and technique.

Moreover, of a painter as important as Giotto we do not even know his real name, because “Giotto” is but a nickname, in reality we can assume that he was called either Biagio or Ambrogio, thus “Biagiotto” or “Ambrogiotto” later shortened, but it is not possible to establish this with certainty. Regarding his beginnings we also have no certain information. We can only speculate about his collaboration in some works made by Cimabue, on a purely stylistic basis. There is then the knot of the "Giotto question," or the problem of the attribution of the frescoes in the Upper Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi, which has aroused much controversy among scholars, since not all attribute the work to Giotto. However, the scarcity of information on the early part of his career does not obscure the greatness of one of the greatest artists in art history.

|

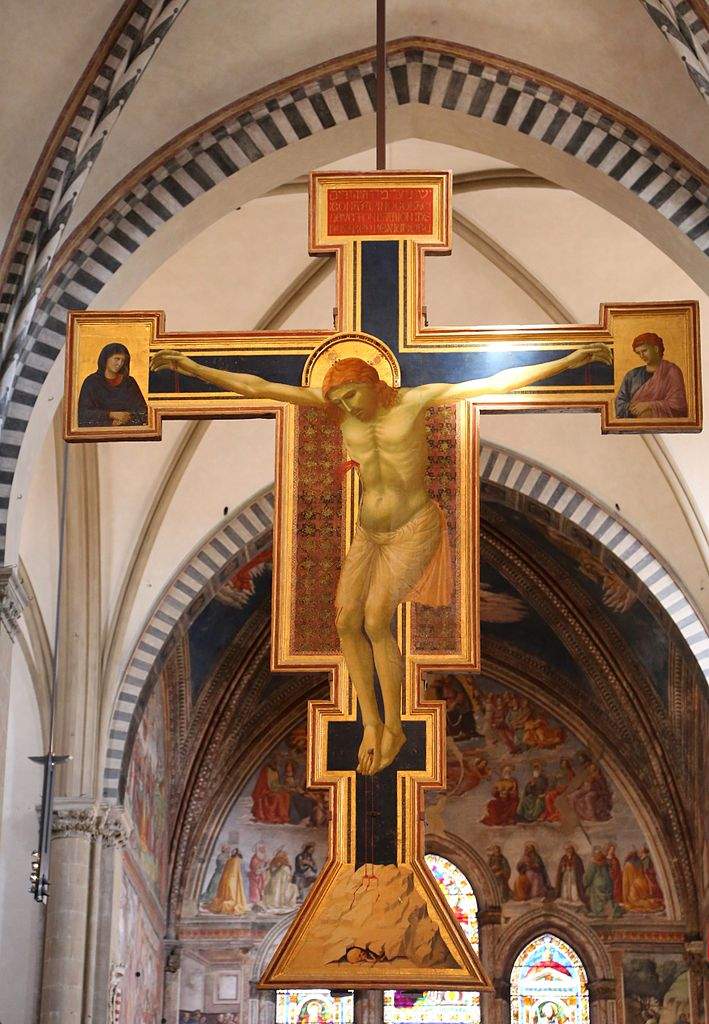

| Giotto, Crucifix (ca. 1295-1300; tempera and gold on panel, 578 x 406 cm; Florence, Santa Maria Novella) |

Giotto was born around 1267, perhaps in Vespignano, Mugello, but more likely in Florence: in any case, from childhood he was in the city with his family. Between the 1970s and 1980s he completes his training probably having Cimabue as his teacher. Perhaps he also makes a trip to Rome. Around 1295 he began work on the Crucifix in Santa Maria Novella, one of his best-known masterpieces. At the same time he may have begun work on the frescoes in the Upper Basilica of Assisi in this year. However, Giottesque authorship of the Assisi frescoes is still the subject of investigation and heated debate. Around 1300 he painted the Stigmata of St. Francis for the church of San Francesco in Pisa: the painting is now in the Louvre. In 1300 Giotto was in Rome where he made some works that have not survived.

In 1303 the wealthy Paduan banker Enrico Scrovegni decided to entrust Giotto with the fresco decoration of the celebrated chapel that bears his name, the Scrovegni Chapel. Work on what is one of the world’s greatest temples of art would end two years later. Around 1304 Giotto worked in Rimini where he executed the Crucifix preserved in the Malatesta Temple, the so-called Rimini Crucifix. Around 1306 the artist worked on the frescoes in the Palazzo della Ragione in Padua, which were destroyed during a fire in the 15th century, while in 1309 he was back in Assisi where he worked on the frescoes in the Lower Basilica.

Giotto returned to Florence in 1310 and executed the Madonna di Ognissanti, now in the Uffizi, in the room that also displays Duccio di Buoninsegna ’s Madonna Rucellai and Cimabue’s Maestà. In about 1318 he began work on the Peruzzi Chapel in Santa Croce in Florence, while perhaps in 1320 he was in Rome where he received a commission for the Stefaneschi Polyptych. Around 1325 he executed the frescoes in the Bardi Chapel in Santa Croce in Florence, and three years later, in 1328, he moved to Naples where he worked for the Anjou family. He remained in the Neapolitan city until 1333, after which, in 1334, he made a sojourn in Bologna, and in the same year, on April 12, he was appointed head master of theOpera del Duomo in Florence: on July 18, he began the construction of the bell tower of the Duomo of Santa Maria del Fiore according to his design. However, Giotto managed to see only the second floor completed, and following his death his original design was modified. In 1335 he made a stay in Milan, the last trip of his career. The artist died on January 8, 1337, in Florence: his last Florentine work, later finished by his collaborators, are the frescoes in the Cappella del Podestà in the Palazzo del Bargello, where the oldest extant portrait of Dante Alighieri can also be seen.

|

| The Scrovegni Chapel |

|

| Giotto, Madonna and Child Enthroned, Angels and Saints known as the Majesty of All Saints (c. 1300-1305; tempera on panel and gold ground, 325 x 204 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery, inv. 1890 no. 8344) |

|

| Giotto, Crucifixion with Five Franciscans (c. 1308-1310; fresco; Assisi, Lower Basilica) |

There are only three works signed by Giotto: the Stigmata of St. Francis, the Baroncelli Polyptych(more on that here) and the Bologna Polyptych. However, the journey through Giotto’s art can begin earlier, with the Crucifix in Santa Maria Novella. Giotto’s Christ, dated between 1295 and 1300, represents a great revolution in the history of art, because from a depiction of a geometrizing Christ, such as the earlier painted Crosses were, we arrive for the first time at a truthfully painted Christ, with a bodily rendering that becomes much more natural than that of earlier achievements. Thus those rigid and schematic features of the thirteenth-century crosses disappear and instead a more natural Christ appears. And then in the same way the weight of Christ is also treated realistically: there is no longer the exaggerated arching that had characterized the earlier counterparts, but the weight is discharged downward in a natural way. With this Crucifix, Jesus almost ceases to be an abstract and distant deity, as he appeared in the previously painted crosses, and instead begins to acquire a much more human dimension, and this Crucifix is precisely one of the pinnacles of Giotto’s painting.

Central to Giotto’s art (and the history of medieval art in general) is the Scrovegni Chapel, commissioned from Giotto in 1303, after its consecration on March 25, 1303. Enrico Scrovegni, the Paduan banker who had the chapel erected, was the son of a usurer, named Rinaldo or Reginaldo, and according to one traditional interpretation it is assumed that he had the chapel built and later decorated to atone for his father’s sins and thus also to rehabilitate the family’s name and image, but according to recent interpretations the chapel may also have been built to celebrate the power of Enrico Scrovegni, who had become one of the most prominent citizens of Padua. The cycle is impressive and starts with the stories of Joachim and Anne, parents of the Virgin Mary, then we have the stories of the Virgin, those of Jesus, and finally depictions of the vices and virtues. Those who enter the Scrovegni Chapel therefore make a journey that takes the viewer through the lives of Jesus, his mother, and his grandparents, and then through the vices and virtues to the depiction of the Last Judgment on the counter-façade, which was meant to be a warning to anyone visiting the chapel. Giotto finished the impressive cycle in 1305, two years after work began. Particularly innovative is the way in which Giotto describes the affections and feelings felt by the protagonists: no longer hieratic and solemn figures as was the case in earlier painting, but a living humanity, sometimes externalizing feelings even very strongly as can be observed from what is perhaps the most famous scene of the cycle, namely the Lamentation over the Dead Christ, where the despair of the protagonists is tangibly evident. Also of notable importance are the choruses that are painted on the wall of the triumphal arch: here, Giotto tries to provide a realistic perspective representation of the cross vaults. With the Scrovegni Chapel, therefore, Giotto continues with his research, renews his art by proposing a very clear, refined colorism, which helps to give volume to the bodies, thus making them more realistic than ever before.

On his return from Padua, Giotto painted another of his greatest masterpieces, the Madonna of All Saints, which has been in the Uffizi since 1919 (it was previously in the Gallerie dell’Accademia where it was moved in 1810 from its original location, the church of All Saints). It was made around 1310 (at least this is the most critically accepted dating). However, some similarities are noted with the figures painted in the Scrovegni Chapel so there are those who speculate that it was made by Giotto precisely on his return from the Veneto. It is a work of great importance that allows us to get to know the plasticity of Giotto’s figures: the figure of the Madonna is very solid, endowed with a wholly classical composure that completes an ideal path begun years earlier with the Madonnas in Majesty made by Cimabue and Duccio di Buoninsegna (these two are the very artists with whom the Madonna of All Saints is compared in the Uffizi). Interesting in Giotto is a particular element of novelty compared to his predecessors: the fact that the Madonna is inserted below a marble aedicule seen in foreshortening, which is very elegant and reminiscent of solutions typical of Gothic sculpture (for example, the ciboria of Arnolfo di Cambio). This aedicule and the arrangement of the saints on the sides on different planes contribute to a feeling of depth, and this despite the gold background.

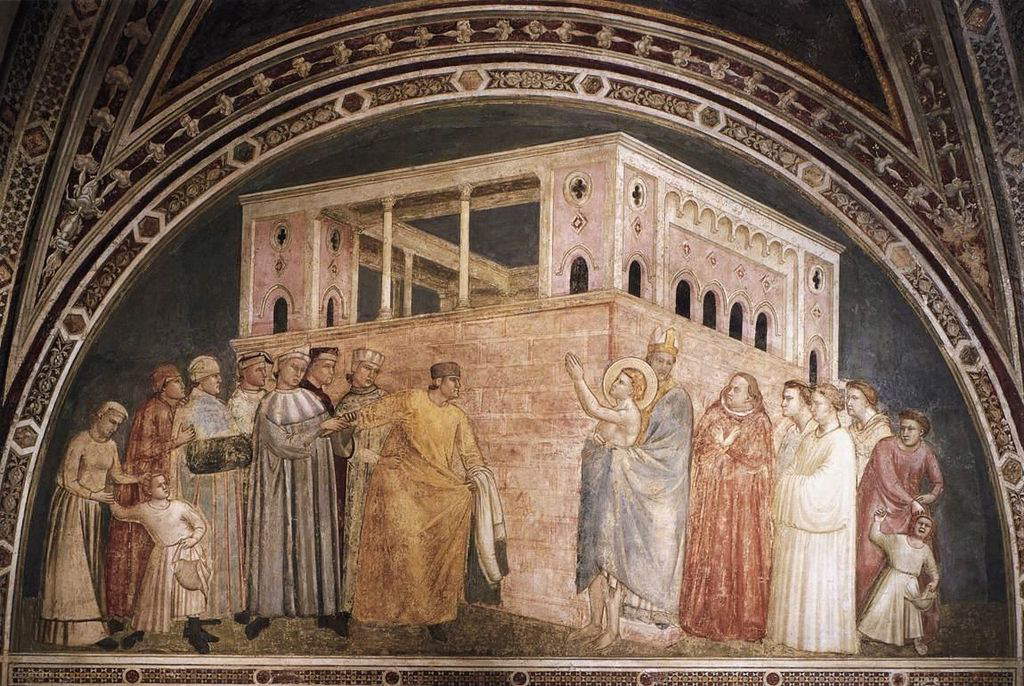

Finally, among the most important late works are the frescoes in the Bardi Chapel in Santa Croce in Florence, painted around 1325. To date it there is one sure term: in fact the figure of St. Louis of Toulouse, who was canonized in 1317, appears in the frescoes, so the realization cannot be earlier than this date. The theme with which Giotto began his career, namely the stories of St. Francis, returns. The frescoes in the Bardi chapel are marked by the monumentality that had distinguished the Peruzzi chapel (also in Santa Croce), but here Giotto continues his quest toward a better formulation of spatiality and light in the compositions, which in the case of the Bardi chapel reach a clarity that communicates very well the sense of solemnity of the scenes, with a greater clarity and simplicity than in the Peruzzi chapel, and above all we see a more realistic delineation of space than in the earlier achievements. The Bardi Chapel is in essence the masterpiece of Giotto’s maturity.

|

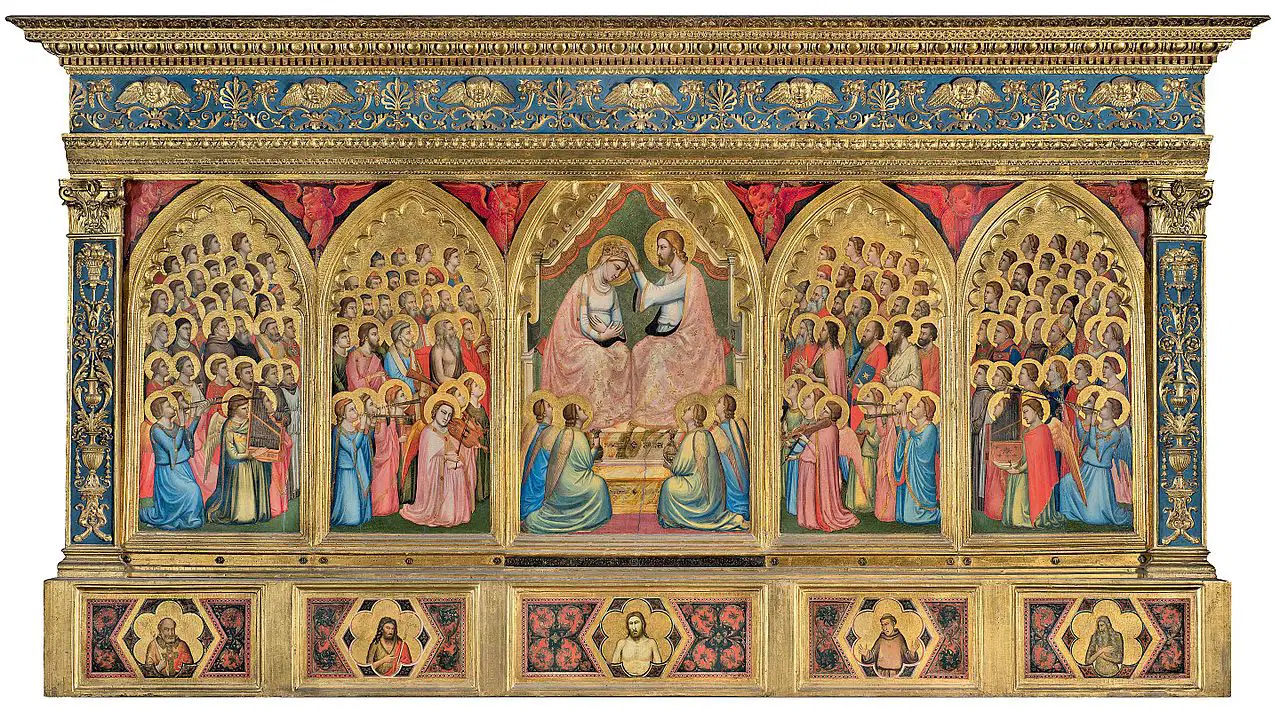

| Giotto, Baroncelli Polyptych (c. 1328; tempera and gold on panel, 185 x 323 cm; Florence, Santa Croce) |

|

| Giotto, The Renunciation of Goods (c. 1325; fresco; Florence, Basilica of Santa Croce) |

The journey through Giotto’s art must necessarily start in Florence: here you can admire one of his earliest masterpieces, the Crucifix of Santa Maria Novella in the basilica of the same name, and around the same time dates the Madonna of San Giorgio alla Costa preserved at the Diocesan Museum of Santo Stefano al Ponte. At the Uffizi, on the other hand, it is possible to admire the Madonna di Ognissanti and the Badia Polyptych, while the Galleria dell’Accademia preserves a Shepherd’s Head, a fragment of a fresco cycle from the Badia Fiorentina. At the Church of Ognissanti, on the other hand, one can see the Cross of All Saints, and then still to be seen, in Santa Croce, are the frescoes of the Bardi and Peruzzi chapels as well as the Baroncelli Polyptych, whose cymatium, theEterno c on the Angels, is at the San Diego Museum of Art in California. Still in Florence, the Horne Museum holds a St. Stephen by Giotto. The Giottesque tour can end with the frescoes in the Cappella del Podestà, the artist’s last work.

One cannot say one has known Giotto without seeing the frescoes in the Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi: those in the Lower Basilica are definitely his, the Stories of Isa ac are attributed to the so-called “Master of Isaac,” who, however, according to some others is none other than the young Giotto, while the Stories of St. Francis represent one of the most debated works in the history of art, traditionally attributed to Giotto, until, in 1791, Guglielmo Della Valle questioned Giotto’s authorship, only to be challenged just five years later by Luigi Lanzi. The problem of authorship exploded in the second half of the twentieth century, with various scholars lined up for and against: the hypothesis that meets with the most success is the one that wants Giotto included in a worksite with several aides, even more experienced than himself. Similarly, it is impossible to say you know Giotto without ever having seen the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua. Also in the Venetian city, the Civic Museums at the Eremitani preserve an important painted cross by Giotto. Also in the north, see the Bologna Polyptych at the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna and the Rimini Crucifix in the Malatesta Temple in the Romagna city. In Rome, the Pinacoteca Vaticana preserves the Stefaneschi Polyptych. Abroad, there are works by Giotto in the Louvre (the Stigmata of St. Francis originally in Pisa), the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin (the Dormitio Virginis), the Alte Pinakothek in Munich (the Crucifixion, theLast Supper and the Descent into Limbo), the National Gallery in London (the Pentecost), at the Metropolitan in New York (theAdoration of the Magi), at the Isabella Stewart-Gardner Museum in Boston (the Presentation in the Temple), at the North Carolina Museum of Art (the Peruzzi Polyptych, executed with extensive use of the workshop), and at the National Gallery in Washington (a Madonna and Child).

|

| Giotto, life and works of the artist who "remolded the art of painting" |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.