Giovanni Bellini, also known as “il Giambellino” (Venice, c. 1430 - 1516) is one of the great names in Italian art history, as he is considered the initiator of the Renaissance in Venice. Born into a family of painters (his father Jacopo and his brother Gentile were among the most important artists in 15th-century Venice), he soon managed to break free from the late Gothic schemes within which he was trained to embrace first the art of his brother-in-law Andrea Mantegna (Isola di Carturo, 1431 - Mantua, 1506), then that of Piero della Francesca (Borgo Sansepolcro, 1416 - 1492) and again that of Antonello da Messina (Antonio di Giovanni de Antonio; Messina, 1430 - 1479), who made his art brighter and softer: ready, then, to pave the way for Venetian tonal painting, which would find in Giorgione its most important heir.

The artist spent his entire career in mid-15th-century Venice, at a time when the city, which saw itself threatened by the Turks over its dominance of the seas, had begun to embark on its expansionism towards the mainland, which began as early as the beginning of the 15th century: important in this regard was the conquest of Padua in 1405, a fact of considerable significance for the cultural and artistic development of Venice. Indeed, Padua had a university and a more refined intellectual class than Venice, not to mention the fact that it would soon be home to some of the great artists of the Tuscan Renaissance, such as Donatello to Paolo Uccello. Tuscan artists would soon begin working in or for Venice: the city, in its expansion on the mainland, found itself in conflict with the in turn expansionist policies of the Duchy of Milan, and to stem the Milanese danger, Venice allied with Florence. So, soon political contacts also gave rise to considerable cultural contacts, and among the artists who sojourned in Venice it is necessary to mention Lorenzo Ghiberti, Michelozzo, Leon Battista Alberti, Paolo Uccello himself and others, all of whom were present in the city in the 1520s and 1530s, and it is possible to speculate that some of these presences were due to the fact that Cosimo il Vecchio, in exile from Florence, after having been in Padua settled for some time in Venice and thus some artists followed him. This climate of cultural fervor thus succeeded in renewing Venetian art, at that time still dominated by late Gothic tastes, which nevertheless dictated trends for some time to come: however, this was the season during which the Venetian Renaissance was inaugurated, which then received a very important impetus thanks to the contribution of the art of great masters such as Andrea Mantegna, Piero della Francesca and Antonello da Messina. This was the climate within which Giovanni Bellini moved.

The artist had trained in the workshop of Jacopo Bellini, an important late Gothic-trained painter who had then embraced some Renaissance innovations (his brother Gentile, another important Venetian painter of the time, was also active in his father’s workshop). In addition to his father, Giovanni Bellini also looked to the art of the Vivarini family, especially to Antonio Vivarini, another great name in early 15th-century Venetian art, but decisive for his training was his encounter with Andrea Mantegna, whose brother-in-law Giovanni Bellini would also become (in fact, in 1453 Mantegna married Giovanni and Gentile’s sister, Nicolosia). And Giovanni Bellini’s early works are affected precisely by Mantegna’s influence.

|

| Giovanni Bellini, Madonna and Child (c. 1475; 83 x 62 cm; Rovigo, Palazzo Roverella) |

Giovanni Bellini was born around 1430 in Venice into a family of painters: his father Jacopo was one of the most important painters of the time and his brother Gentile was to become, also, a leading artist. He completed his apprenticeship in his father’s workshop, but of his early years we have very little certain information. The first document that mentions him dates from 1459, in which he appears as a witness for a Venetian notary. In the meantime he had met Andrea Mantegna, had become his brother-in-law in 1453 (as Mantegna had married his sister Nicolosia), and had begun to produce some works with a clear Mantegna flavor, such as the Transfiguration in the Museo Correr in Venice or the Presentation in the Temple now in the Fondazione Querini Stampalia in Venice (which, however, may have been done around 1460). Around 1460 he painted the famous Pietà now in the Pinacoteca di Brera, and in 1464 he began the Polyptych of St. Vincent Ferrer for the Basilica of Saints John and Paul in Venice, a work that was perhaps finished three years later.

In 1470 he is commissioned to execute a painting for the Scuola di San Marco, a Universal Deluge, but he will never complete the undertaking. In the same years he probably made a sojourn in the Marche region, where he came into direct contact with the art of Piero della Francesca. Also in the 1470s, he met Antonello da Messina and painted the Pesaro Altarpiece. In 1479, after his brother Gentile left for Constantinople, he obtained the commission, previously assigned to Gentile, to restore some paintings in the Doge’s Palace in Venice. In 1483 he was appointed official painter of the Republic. Around 1487 he painted the St. Job Altarpiece, and in 1488, together with his brother Gentile, he worked on some paintings for the Sala del Maggior Consiglio in the Doge’s Palace. In the same year he produced the Triptych of the Frari.

Perhaps around 1490 he began to paint one of his best-known masterpieces, theAllegoria sacra preserved today in the Uffizi, one of the most problematic and debated paintings in art history(read an in-depth discussion of the painting here). In 1496 Giovanni came into contact with Isabella d’Este, with whom he negotiated for a painting intended for the marquise’s studiolo in Mantua. Probably by 1502 Giovanni finished the Baptism of Christ for the church of Santa Corona in Vicenza. In contrast, the St. Zaccaria Altarpiece for the church of the same name in Venice dates from 1505. In 1507, following the death of his brother, he finished alone the Preaching of St. Mark in Alexandria begun by Gentile (now in the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan), one of his greatest and most famous masterpieces. In 1514 he painted the Feast of the Gods, now at the National Gallery in Washington, his last major work. The artist died in Venice on November 29, 1516: his last undertaking, a Martyrdom of St. Mark commissioned by the Scuola Grande di San Marco, remained unfinished, and would not be finished until 1537 by Vittore Belliniano, his longtime collaborator.

|

| Giovanni Bellini, Sacred Allegory (variously dated between 1487 and 1504; oil on panel, 73 x 119 cm; Florence, Uffizi) |

|

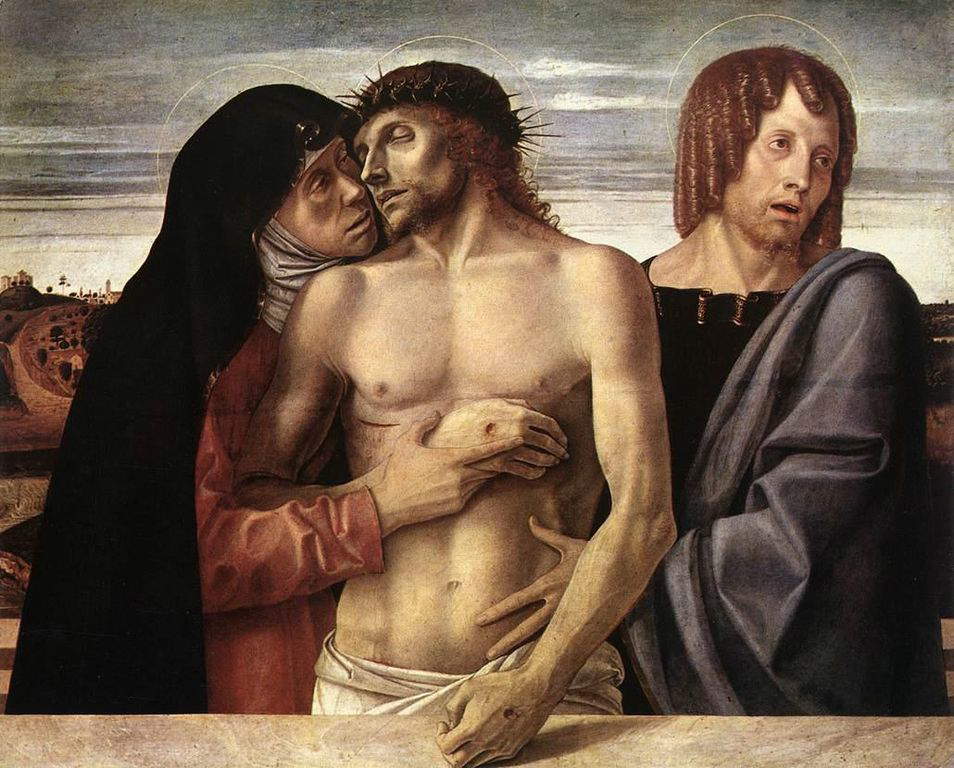

| Giovanni Bellini, Pietà (1460-1465; tempera on panel, 86 x 107 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera) |

|

| Giovanni Bellini, Presentation in the Temple (1460; tempera on panel, 80 x 105 cm; Venice, Fondazione Querini Stampalia) |

Giovanni Bellini’s early works are greatly influenced by his closeness to Andrea Mantegna. The meeting between Giovanni Bellini and Andrea Mantegna may have taken place not in Venice but in Padua, where Mantegna was active in the very fifties of the fifteenth century, and where Bellini himself may have been in the fifties: the Pietà preserved at the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo is in fact exemplified by Donatello’s Dead Christ from the altar of the Saint in the Basilica of Sant’Antonio, a work was of capital importance for the Renaissance in northern Italy, because Donatello’s manner contributed to a strong renewal of both the northern artists’ way of making art and iconographies, and this is also testified by the fact that his Dead Christ was very successful, as indeed Bellini’s Pietà also demonstrates. Another possible reference for the Pietà could be Mantegna himself, with his Polyptych of St. Luke kept in the Brera Pinacoteca, but which had been painted for the church of santa Giustina in Padua in 1454: in the polyptych one can see a dead Christ between the Madonna and St. John, and Giovanni Bellini may have taken cues from the Mantegna precedent. The closeness to Mantegna, however, becomes quite tangible in the Transfiguration, a work made after 1455 that is now in the Museo Correr in Venice and can be directly compared with Mantegna’sOration in the Garden, painted around the same time and now in the National Gallery in London. The rocky landscape is the same, just as entirely similar to Mantegna’s is the harsh, hard mark we see not only in the rocks but also in the garments and features of the characters, a hard line that in Mantegna made tangible the fact that the artist was inspired by classical antiquity. In contrast, the interest in archaeology, which is one of the main motifs of Mantegna’s art, is entirely secondary if not almost completely absent in Giovanni Bellini’s art of this phase: the Venetian artist is more interested in making the characters converse with the nature around them, and this expedient also serves to make the viewer’s attention focus on the figures. A further work, the Presentation in the Temple of about 1460, which is in the Fondazione Querini Stampalia in Venice, allows for a further direct comparison with Mantegna because it is a copy of a counterpart work by his brother-in-law, made a few years earlier and preserved today in Berlin. From an initial analysis, one can see the significant conceptual differences between the two works: more detached that of Mantegna, more human instead that of Bellini, who eliminates the haloes of the saints, also eliminates Mantegna’s frame leaving only a balustrade to bring the characters closer to the viewer, and more freely adds some characters on the right, but also a woman on the left.

The first work to show signs of detachment from Mantegna’s manner, however, is the Pietà in the Pinacoteca di Brera: the detachment is mainly felt by the fact that Giovanni Bellini wants to make further evolutions in bringing the protagonists of his painting closer to the viewer. The figures are painted in full scale, but not only that: Giovanni Bellini’s intent is to make the suffering of the Madonna and Saint John clearly perceptible. The artist thus succeeds in painting a representation characterized by high humanity, overcoming the idealization that had characterized Venetian painting until then and inaugurating the Renaissance in Venice. It is humanity that is the main characteristic and of this work of art, it is the ability to communicate that the characters we see in the work are not abstract deities but are men of flesh: and Bellini was aware of his means because the Latin inscription, taken from a verse by Propertius, reads pi “when these swollen eyes make you almost weep, then the work of Giovanni Bellini may also weep,” as if to say that the intent of the painting is to move the viewer. This interest in the humanity of the characters may have been suggested by viewing some Flemish works. Moreover, the overcoming of the Mantegna lesson can also be seen in the fact that the stroke begins to soften.

Further evolutions of Giovanni Bellini’s style are seen with the Pesaro Altarpiece, which depicts a Coronation of the Virgin and is kept in the Pesaro Civic Museums (the cymatium, with a Pietà), is in the Pinacoteca Vaticana. It had been painted for the local church of San Francesco, around 1470-1475: Giovanni Bellini was in Pesaro for a stay in his stepmother Anna’s native lands. The coronation of the Virgin takes place on earth and not in heaven, as the iconographic tradition wanted, and both the Madonna and Jesus are seated on a large classical marble throne that has an open back, however, so that the viewer can catch a glimpse of the landscape with a village on a hill (this could be the village of Gradara in the Marche region of Italy). In this painting Giovanni Bellini succeeds in definitively detaching himself from the harshness of the Mantegna sign that had not left his art up to that point, and he succeeds in his intent by embracing the art of Piero della Francesca: the light, of Flemish derivation, that spreads throughout the painting and invests all the characters, succeeds in giving a greater softness and brilliance to their robes and faces. Unlike Piero della Francesca, however, who used his terse light to propose an intellectual and highly rational art, Giovanni Bellini uses this light by reworking it in a naturalistic key (one only has to see the gaunt face of St. Francis or the distracted gaze of St. Paul to realize that Giovanni Bellini’s intent is to humanize his characters, unlike Piero della Francesca). The novelty of Giovanni Bellini’s insights into the use of light and color can then be easily seen in one specific detail, namely the fact that the shadows, in the Pesaro altarpiece, are colored. These insights of Giovanni Bellini would be the prelude for the birth of Venetian tonal painting (or “tonalism”), painting that builds depth in scenes through the juxtaposition of colors.

Even in the later stages of Giovanni Bellini’s career we see new modifications of his style: in the early sixteenth century, in fact, Bellini was so fascinated by Giorgione’s achievements that he decided to make them his own. This is seen in the 1505 Sacra Conversazione preserved at the church of San Zaccaria in Venice, also known as the San Zaccaria Altarpiece, one of the few dated and signed works by Giovanni Bellini. It is a spectacular painting that echoes the scheme of the San Giobbe altarpiece, although here the links with the past are dissolved and the artist embraces a Giorgionesque tonalism that is most noticeable in the way Giovanni Bellini paints his characters, who are now constructed only with color. Magnificent is the architecture within which the scene takes place, a classical niche decorated with a mosaic of motifs from the world of nature, which dialogues strikingly with the architecture of the church (it almost seems as if Giovanni Bellini’s painting is a natural continuation of the chapel in which it is located). It is also interesting, then, how Giovanni Bellini manages to give naturalness to the connotations of his characters without, however, causing them to lose the typically Venetian solemnity derived from Byzantine art. Bellini also uses a varied palette, with warm colors: this is the artist’s first work in which his interest in the art of Giorgione, who was about forty years younger than him, is shown. This interest will also emerge from later works.

|

| Giovanni Bellini, Pesaro Altarpiece (c. 1471-1483; oil on panel, 262 x 240 cm; Pesaro, Musei Civici) |

|

| Giovanni Bellini, San Zaccaria Altarpiece (1505; oil on panel, 500 x 235 cm; Venice, San Zaccaria) |

Giovanni Bellini was a very prolific artist, so today we know many of his works. To get a closer look at his art, it is necessary to visit Venice by going to the city’s palaces, museums, and churches. The Correr Museum holds two important early masterpieces, namely the Crucifixion of San Salvador and the Transfiguration (as well as the slightly later Dead Christ Supported by Two Angels). At the Fondazione Querini Stampalia is one of his masterpieces, the Presentation in the Temple. Other works can be found at the Gallerie dell’Accademia: the Triptych of St. Sebastian, the Triptych of St. Lawrence, the Triptych of the Madonna, the Triptych of the Nativity, the Martinengo Altarpiece, the Madonna Contarini, as well as one of his major masterpieces, the Altarpiece of St. Job, and several of his Madonnas such as the Madonna of the Alberetti and the Madonna of the Red Cherubs. Also not to be missed are the Frari Triptych at the Basilica of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, the Saint Zaccaria Altarpiece in the church of San Zaccaria, the Saint Vincent Ferrer Polyptych in the Basilica of Saints John and Paul, and the splendid altarpiece with Saints Christopher, Jerome and Ludwig of Toulouse in Saint John Chrysostom.

Then there are several Italian museums that preserve important works by Giovanni Bellini. The Accademia Carrara in Bergamo preserves several of his works: the youthful Dead Christ between the Virgin and John the Evangelist, the Lochis Madonna, the Portrait of a Young Man, and the Madonna of Alzano. At the Uffizi there is the celebrated Allegoria sacra, the Pinacoteca Malaspina in Pavia houses a youthful Madonna and Child, in Milan the Pinacoteca di Brera houses another youthful masterpiece, namely the Dead Christ supported by Mary and John, as well as the Greek Madnna, while at the Poldi Pezzoli there is the Christ in Pity in the Tomb. The Musei Civici in Pesaro house a masterpiece of his maturity, the Pesaro Altarpiece, and other works of his are in Rovigo, Palazzo Roverella, the Museo di Castelvecchio in Verona, and the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte in Naples. Also worth seeing is the Baptism of Christ in the church of Santa Corona in Vicenza. Abroad there are important works in the Louvre, the National Gallery in London, the Staatliche Museen in Berlin, the Prado in Madrid, and the Metropolitan in New York. The last major work, the Feast of the Gods, is in the National Gallery in Washington.

|

| Giovanni Bellini, life and works of the initiator of the Venetian Renaissance |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.