Realism was an artistic and literary current that arose in France around the middle of the 19th century, which, in adherence to developments in national political and social history, disrupted the ideals of Romanticism, rejecting imaginative idealization in favor instead of careful observation and reproduction of nature and contemporary life.The term realism, broadly understood as a stylistic direction that aims at the closest adherence to reality, is referable to various moments in art history, and includes the tendency in literature and the figurative arts toward the faithful representation of reality with verisimilar details, which prevails over the artist’s interpretation and sentimentality.

Limited to the precise historical meaning of nineteenth-century Realism, it is more a literary and pictorial orientation than a programmatic movement that spread between about 1850 and 1880. In the years, therefore, immediately following the revolution of 1848, when the monarchy collapsed, ushering in the Second Republic (1848-51), and which reached its peak in the period of the Second Empire (1852-1870), characterized by strong economic and technological development. As part of a broader European revolutionary wave that brought wide-ranging social changes to several countries, political events in France throughout the 19th century cast a new light on the margins of society, and Realism became the visual language for their representation.

Realist painters presented a revolutionary character compared to the order established by the Parisian Salons, stimulated by various intellectual inputs that characterized the first half of the 19th century:the anti-Romantic movement in Germany, with its emphasis on thecommon man as artistic subject, the positivist philosophy of Auguste Comte in which the importance of sociology as a scientific study of society was emphasized, and the rise of professional journalism that recorded current events. In addition, the discovery of photography in 1839, with which painting from that time began to contend, was leading to a drive to reproduce visual reality with extreme precision.

The realist painting current involved artists who worked independently, but who shared a common spirit and attitudes. Although they knew each other, and with the realist writers supporting each other, they never formed a group. The historical and artistic motivations that led to the genesis and development of realism, in the art and ethics of the painters, have since found subsequent adherence throughout the world in the generations to come. The greatest exponent of realism in painting was Gustave Courbet, who in the footsteps of the work of Jean-Françoise Millet, a painter of rural scenes of the Barbizon School, rejected the neoclassical and Romantic vision and instead made everyday life the subject matter for his great history painting.Together with Honoré Daumier, a great author of social satires, he contributed to the affirmation of art’s democratic mission by embracing the progressive goals of modernism, seeking new truths through the overturning of traditional value and belief systems.

One of the first appearances of the term Realism was in a literary journal Mercure français du XIXe siècle in 1826, in which the word is used to describe a doctrine based not on the imitation of past artistic achievements, but on the truthful and accurate representation of the models that nature and contemporary life offer the artist. French proponents of realism were in agreement in their rejection of the artificiality of the academies and in upholding the pictorial dignity of real subjects as messages of in an effective work of art. The 1930s saw a push for scientific positivism, the advent of photography as a means of completely objectively capturing reality, as well as caricature as a tool of visual storytelling that took on the colors and tones of political arguments, hand in hand with the first humorous newspapers.

Challenging the vision of Neoclassicism and Romanticism, of artistic creation as an escape from reality in the face of the larger social issues brought by the turbulent 19th century, Realism took hold in France around the 1840s in response to ’alternating governments, military occupation and censorship, and the issues of ’industrialization and urbanization of cities.Realism was an attempt to approach through art the concreteness of the real datum in its also moral and political characteristics. In contrast to an art that idealized characters and events, it contrasted an objective look at its own time that was able to record situations and characters, expressions of the life of the time: the customs of the middle and humble classes, ordinary everyday life and the natural datum without frills. The spiritualistic and literary tendencies of Romanticism were now in crisis, and work was being done in the name of the unexceptional, the ordinary and the unadorned. Through its most important painters, the role of the socially engaged artist and literary author was also manifested, to reproduce all aspects hitherto ignored in the Parisian Salons, such as the attitudes of people and workers, their physical settings and material conditions.

The leading proponent of realism, Gustave Courbet (Ornans, 1819 - La Tour-de-Peilz, Switzerland 1877) was an ardent democrat and led a multifaceted assault on French political power, bourgeois social mores, and the art establishment. He was strongly opposed to idealization in his art and urged other artists, placed in the context of Paris at the time, to consider the frank depiction of scenes of everyday life as atruly democratic art.

With his participation in the Salon of 1850-1851 he marked the debut of Realism, causing a scandal with his concrete depiction of a rural funeral in the tones traditionally reserved for history painting. The massive work The Funeral at Ornans (1849-1850, measuring more than 3 x 6 meters) is considered, by the artist’s own statement, “actually the burial of Romanticism,” opening up a new visual style in an increasingly modern world. He stuck to the facts of a real burial, avoiding amplified spiritual connotations. Through portraits of unknown figures (the revolution of 1848 had established universal male suffrage) Courbet was showing the country’s new political class to frequenters of the Paris Salons.

The explicit establishment of Realism as a significant force in the European art scene, however, came in 1855, the year in which the painter defined and manifested his artistic ideals in a pamphlet written for the Salon - Universal Exhibition in Paris, as the catalog of a self-organized solo exhibition of his work: on that occasion three of the fourteen canvases Courbet had submitted to the jury were rejected, the artist then invented an astonishing way to challenge and respond to this judgment, creating his own outdoor pavilion which he entitled Pavillon du Réalisme and in which he showed forty of his paintings. This act can be considered the manifesto of a new poetics as well as the birth of a new way of doing business for artists. In addition to diverting attention from institutional exhibitions within the Salon he created “publicity” around his work, encouraging artists to exhibit their art independently.

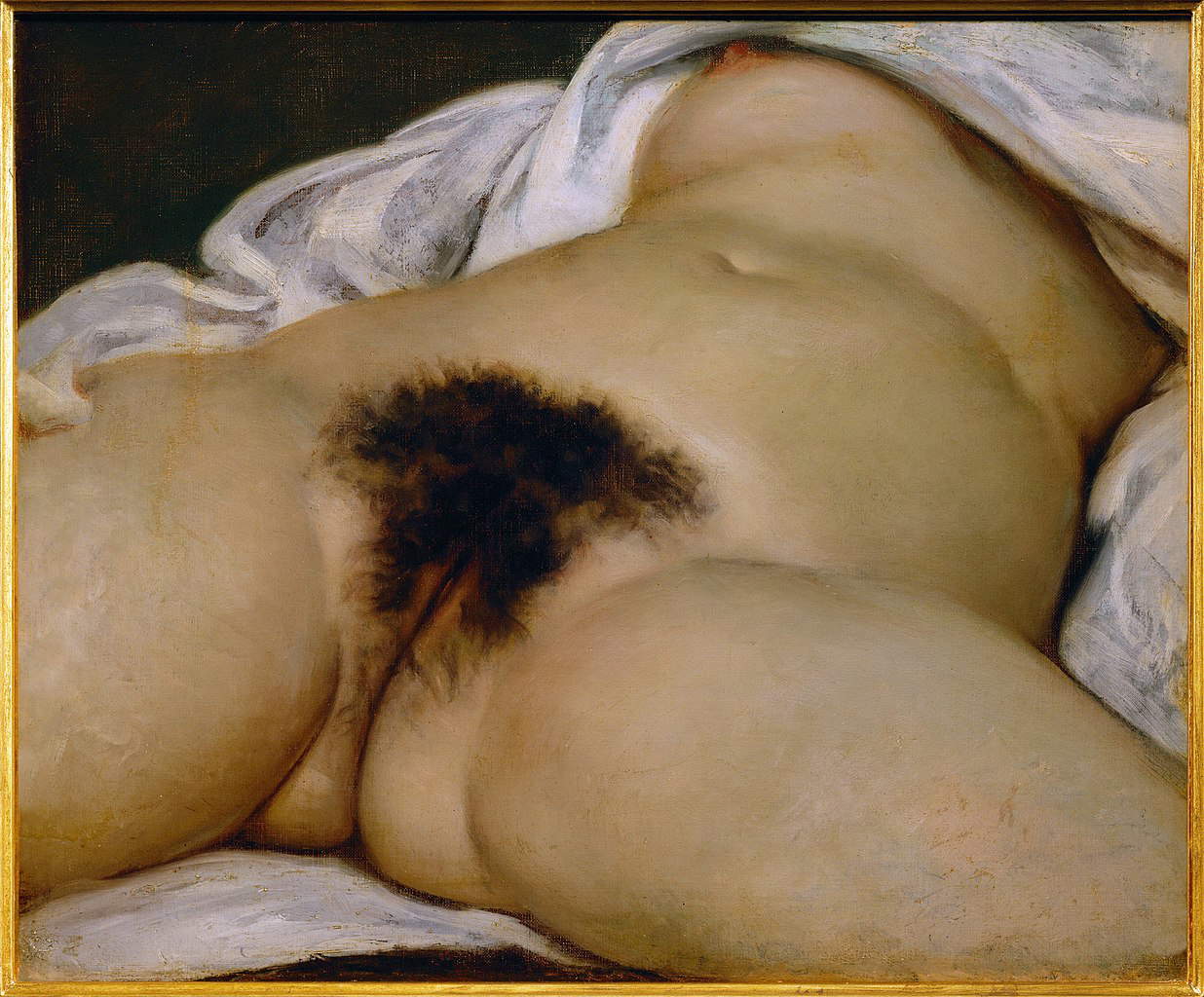

In the history of the Salon, as a Universal Exhibition of Art that originated in 1699, already by 1833 the disagreement between the academic orientation of conservative forces and new artistic trends was gradually becoming more and more pronounced, which reached a point of rupture and no return precisely with the Realism fielded by Courbet with his 1855 pavilion.Courbet painted large works with subjects that challenged the values of French society, and in addition to confusing the traditional categories and subjects of academic painting, he challenged the state institution of art itself. In the 1860s Courbet focused on erotic nudes, hunting scenes, landscapes and seascapes that challenged the norms of his time and in some cases remain problematic to this day(The Origin of the World, 1866).

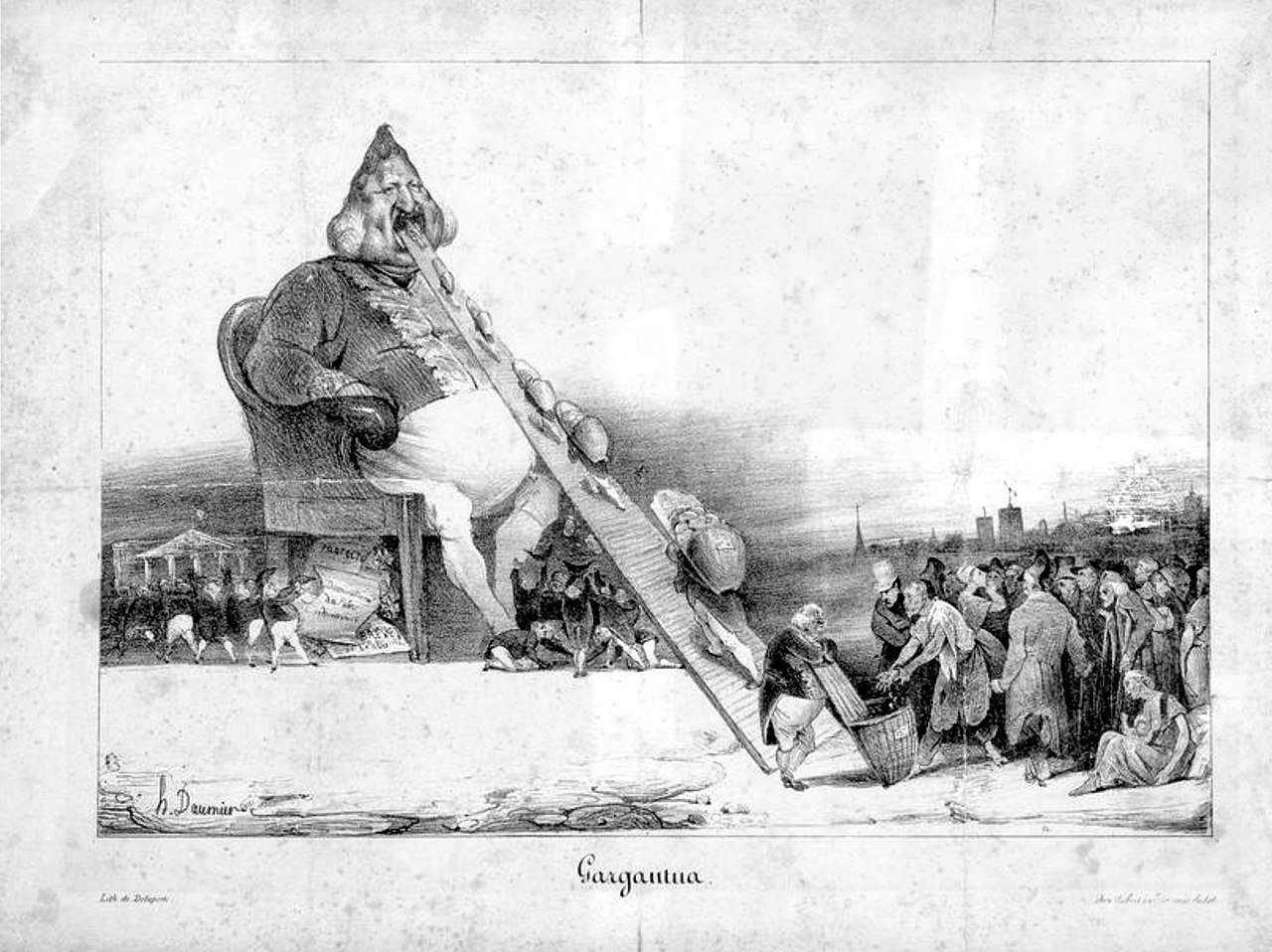

Another great French realist artist was Honoré Daumier (Marseille, 1808 - Valmondois, 1879), who as early as the mid-1830s drew satirical caricatures of French society and politics. Like Courbet, he was a democrat and ended up imprisoned for criticizing the monarchy. In the 1831 lithograph Gargantua, he depicted a fat King Louis Philippe seated on a throne devouring sacks of coins dragged up by petty laborers, representing the throngs of destitute subjects from whom the monarch and his ministers had wrested income through compulsory offerings.

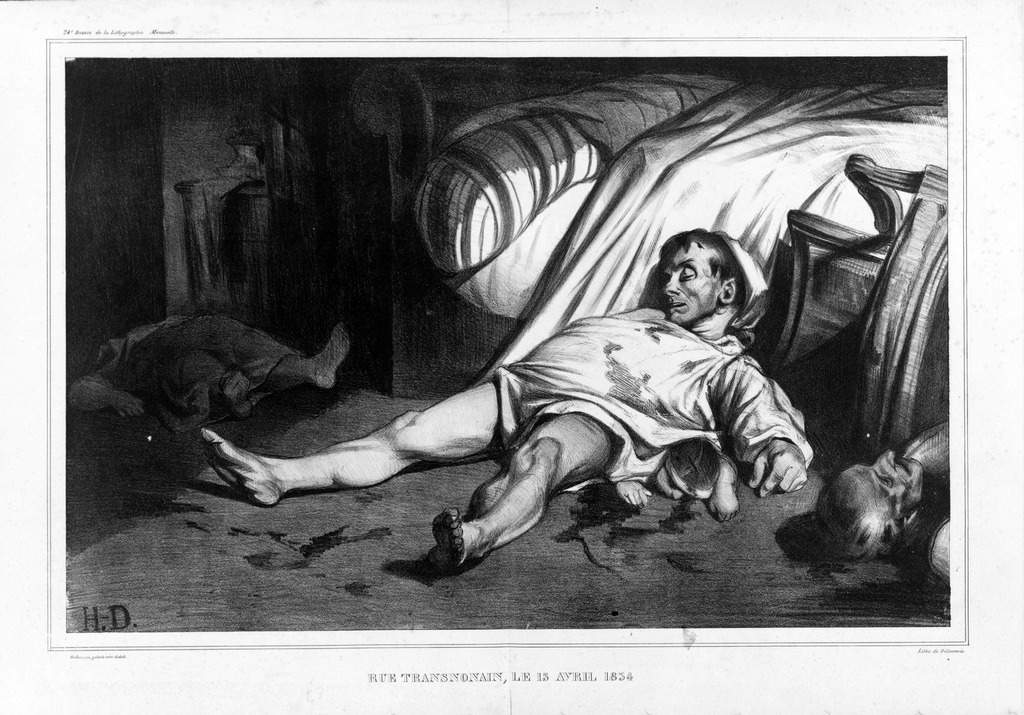

With the wide expansion of journalism and new modes of communication, in the wake of the mechanical and industrial and political revolutions of the 1830s, the popular press, including images that mocked the established order, also became widespread. Daumier was able to use his skill as a caricaturist directly in the service of social goals, but the painter’s career followed government and censorship trends.Engravings, which could be reproduced and disseminated by print, allowed Daumier to circulate his critical compositions, and despite his imprisonment, he continued to create realist lithographs such as Rue Transnonain, April 15, 1834 , which showed the brutal aftermath of a government massacre of working-class innocents.The work was considered so powerful and dangerous to the monarchy that Louis Philippe sent men to purchase as many copies as possible to destroy them.

The caricatures stand out as his most successful works; he was one of the most widely recognized social and political commentators of his time, though he also produced other drawings and watercolors, oil paintings and sculptures. He worked for several decades, pursuing the spirit of denunciation with admirable results, the famous canvas The Third-Class Carriage (1862-64) being an important example.

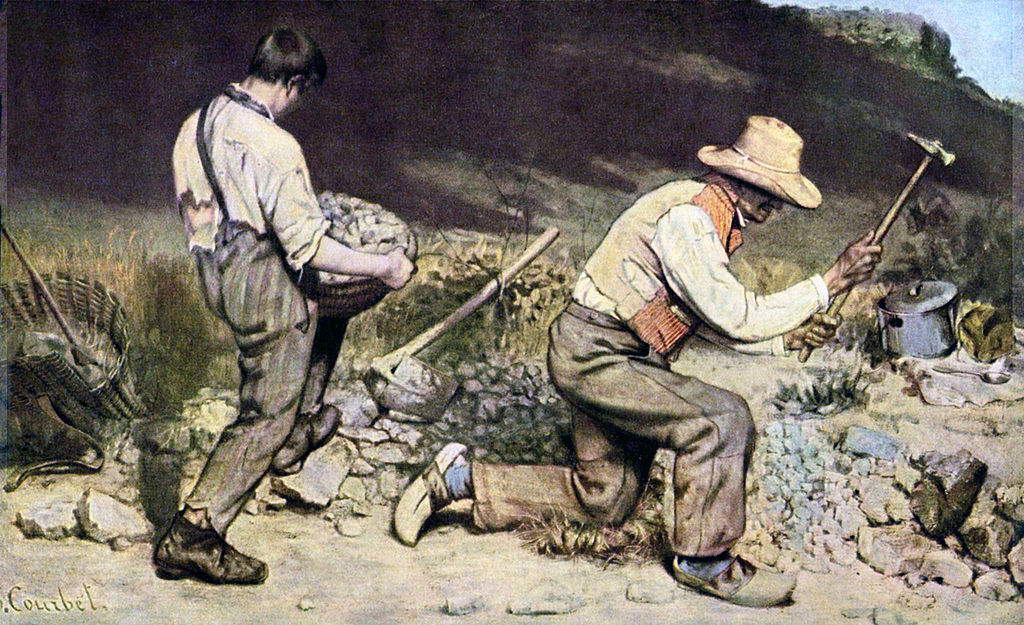

Courbet’s style and subjects of Courbet’s work broke ground already broken by the painters of the Barbizon School, who in theearly 1830s settled in the village of Barbizon near Paris with the aim of faithfully reproducing the local character of the landscape. Although each Barbizon painter had his or her own specific style and interests, they all emphasized the simple and ordinary aspects of nature in their works.They moved away from the melodramatic picturesque and painted solid, detailed forms that were the result of careful observation.With works such as The Gleaners (1857), Jean-François Millet (Gréville-Hague, 1814 - Barbizon, 1875) had been one of the first artists to portray peasant laborers with a grandeur and monumentality hitherto reserved for more important figures.

Courbet equally painted ordinary people, in all their glorious ordinariness, through visceral painting. In eliminating the rhetoric of the academy, Courbet opted for compositions that seemed crude compared to the prevailing sensibility. He began with flat figurations, in which he exalted the contours of forms, and then abandoned careful modeling in favor of applying colors densely, as if through patches that broke the surface. This stylistic innovation made him very influential on later modernists who promoted greater freedom of surface texture in paintings.

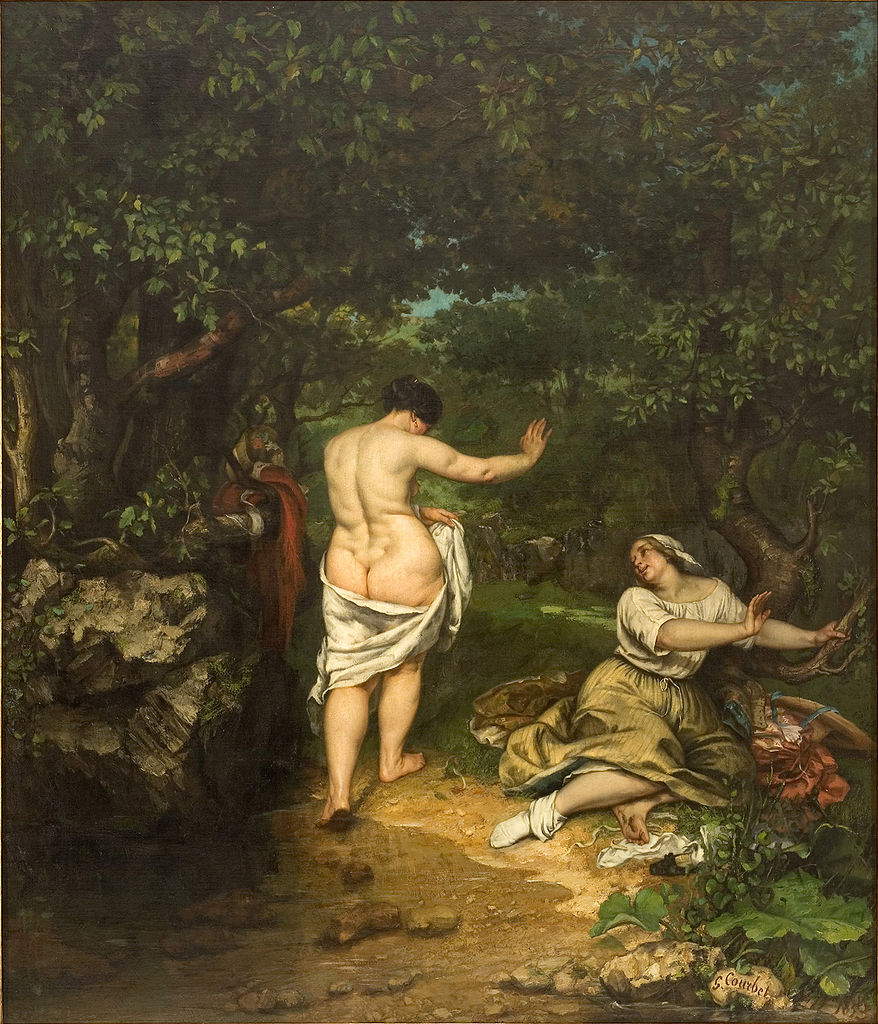

But his prevailing characteristic is especially in his choice of subjects that subverted academic classicism. From The Stone Breakers (1849), which critics accused of deliberate ugliness, to the rough nudes and landscapes, such as the seascapes of his later years, in which the rendering of water is tangible, the paint is dense on the surface creating the illusion of water itself. As for nudes, as early as 1853 in The Bathers he depicted, to the indignation of the public, two ordinary women, without any mythological or rhetorical symbolism, rendered naturally in their unidealized physicality. Just as in The Sleep of 1866 he shifted to an erotic realism that became prevalent in his later work, of which The Origin of the World will be the most innovative, framing a woman’s pubis with open thighs in a scandalous intimate view of the female anatomy described with blunt realism.

Daumier’s painting style with its loose and expressive brushstrokes, eschewing the controlled and smooth surfaces of neoclassical painting, was also energetic and charged with realistic detail, with a sculptural treatment of form that depicted the immorality and ugliness of French society. As mentioned above, his prolific output of two-dimensional caricatures far exceeded his pictorial and sculptural output, however, his work presented peculiarities: the use of color in painting as in watercolor, the range of tones as well as extreme contrasts of light and dark in black-and-white lithographs, and a rawness of sculpted forms.

He lived actively in Paris during a period of political and social unrest, two revolutions and frequent regime changes, a war and a siege. Censorship limited Daumier’s artistic output, but his greatest contribution to art was his ability to capture even the simplest moments of life and infuse them with emotion. The satirical vignettes were devoid of sentimentality while not creating the kind of emotional distance typical in Courbet. The main subject of his work was the human condition.

The watercolors presented contemporary themes and were in high demand in the art market. They had a sketch-like quality and with a documentary slant.His oil paintings of the early period had a caricature-like style, until he also began to spend more time out of town in Barbizon in the company of Millet and the painters of the School, and at that point, in a kind of fusion of styles, his work took on an increasingly painterly look, even in his drawings for lithographs. Recurring themes in Daumier were the everyday life of Paris, train passengers, stage performers or lawyers in court, with attention to the impact of industrialization and urbanization on the working-class population, as seen in the oil paintings The Burden (The Washerwoman) of 1850-1853 or The Third-Class Carriage .Even in his modeled forms in relief and in three dimensions, one of his most successful caricatures being the bronze Ratapoil (1851), he echoed the ruthless realism that lurked beneath the artist’s caricatures.

|

| Nineteenth-century Realism: origins and development, themes and styles of the great painters |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.