The situation of relative political tranquility that had arisen in fifteenth-centuryItaly had the merit of fostering the spread of the Renaissance to different parts of the peninsula.The political situation saw the presence on Italian soil of numerous courts that began to consider it a source of prestige to have in their entourages artists, scientists, and men of letters who knew how to work harmoniously, creating a unique climate of intellectual fervor. Lords therefore competed to secure the services of the leading artists and intellectuals of the time, shaping a patronage (a term derived from Gaius Cilnius Maecenas, protector of men of letters and artists in the Rome of the Emperor Augustus) that knew no precedent in Western history.

However, Renaissance patronage found its foundations as early as the 14th century, a time when there was no shortage of courts that protected artists (such as that of the Carraresi in Padua or that of the Visconti in Milan): however, patronage in the following century became a widespread phenomenon. First, because many cities left a communal-republican form of government to transform themselves into lordships (this is for example the case of Florence), and then because the loss of prestige of the church in the fourteenth century had caused a loosening of thatreligious austerity that had prevented the lords of the time from making an excessive display of their wealth and power (which, on the contrary, happened punctually in the fifteenth century, already in the late Gothic era). Conversely, in the 15th century, patronage also had among its purposes to enhance the prestige of the court. Lords in fact wanted to make their names immortal by investing their wealth and welcoming artists, scientists, and men of letters who could bring prestige to their lineage and their city. States in which this drive did not occur remained on the margins: this is the case, for example, of Siena, which, from being a leading city in the artistic trends of the 14th century, was relegated to a peripheral role.

Patronage also had the effect of beautifying and modernizing cities (including from the point of view of urban planning), not least because art continued to have the same important role in communication that it had had in earlier eras. However, these changes ended up disrupting the social role of intellectuals, who from personalities who had held public offices in the Middle Ages (think, for example, of Dante Alighieri), became professionals whose livelihood was guaranteed by the patron (the forerunner of this type of intellectual disengaged from public office was Francesco Petrarch).

The revival of classical studies, although initiated by such important forerunners as Dante and Petrarch, experienced from the end of the fourteenth century a considerable impetus that grew in the fifteenth century: classical civilization became a model to refer to, from which to draw values, first and foremost that ofman as the center of the universe. And to take up classical studies and adapt them to the present context required the figure of the literati who, had to make this ancient heritage accessible, readapt it according to the modern spirit and dialogue with artists so that figurative art, too, could communicate the Renaissance society’s desire to refer back to antiquity. This is the phenomenon known as humanism, a term that originates from humanae litterae, a formula used to refer to ancient Greek and Roman literature. The study of classicism found valuable help in philology, a discipline that spread widely in Renaissance courts. Humanism also contributed to the evolution of the artist’s role in society: seen in the Middle Ages as a craftsman, the Renaissance artist became a complete figure distinguished by considerable intellectual activity, which became indispensable to his or her art.

The city of Florence also played a leading role in this regard. Florentine humanism, already particularly evolved throughout the first half of the fifteenth century, experienced a major boost with the third of the Medici who came to power in 1434, Lorenzo the Magnificent, who, having become lord of Florence in 1469 (he had succeeded his father Piero, who ruled for only five years, starting in 1464, after Cosimo the Elder’s 30-year term), made his own the intuition, common at the time, that a court that welcomed artists and men of letters and drew up intellectual guidelines could be a remarkable source of prestige. He was not, however, a great patron (a role that fell mainly to other members of the family, as well as to other city lineages, such as the Strozzi and Tornabuoni families), but he knew how to masterfully foster the emergence of a culturally lively climate. The main scholars active at the Magnifico’s court, namely Marsilio Ficino, Pico della Mirandola, Giovanni Argiropulo, and Cristoforo Landino, elaborated a philosophical thought based on Neoplatonism that profoundly influenced contemporary art, and initiated a recovery of patterns, models, and iconography drawn from the ancient world.

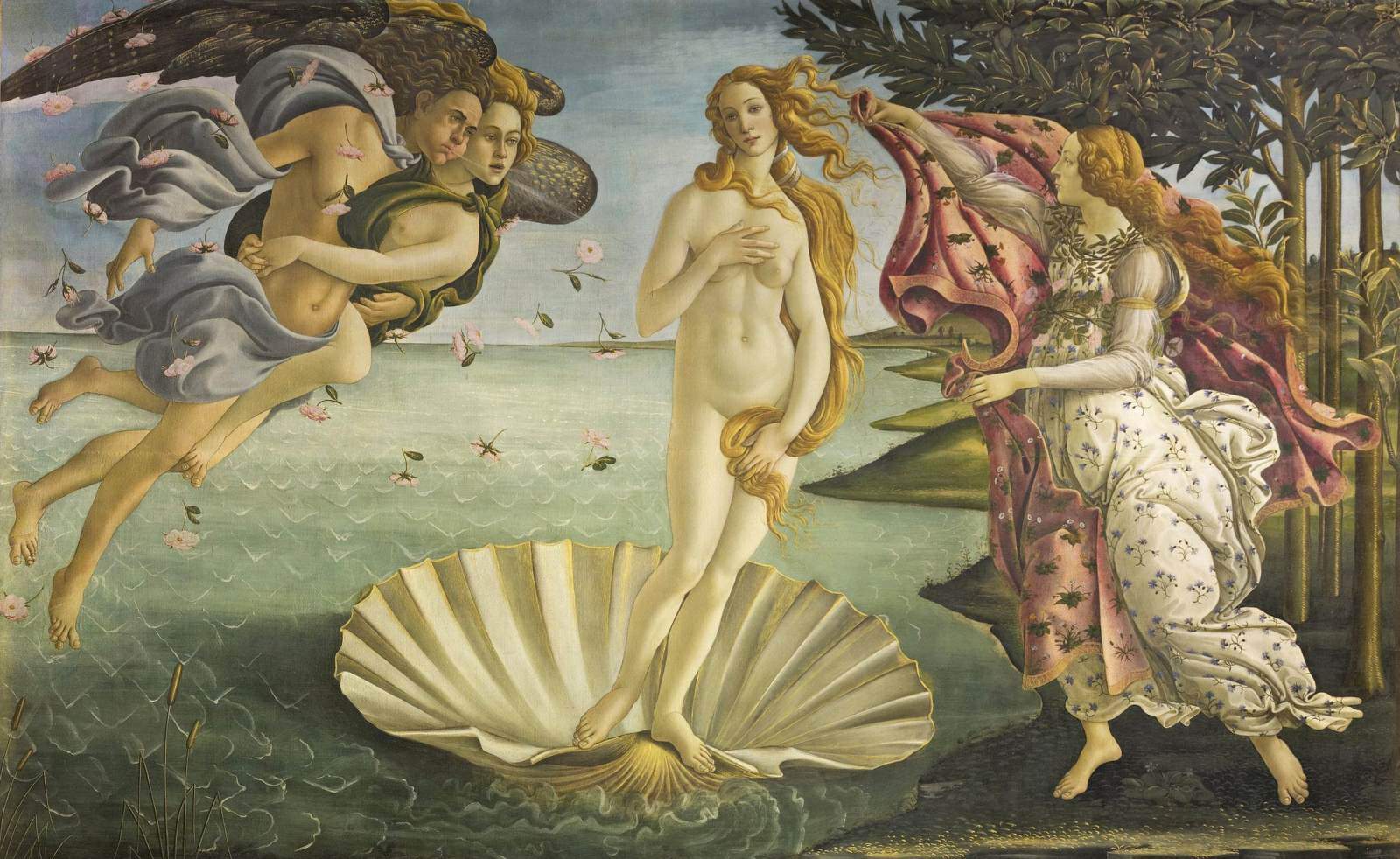

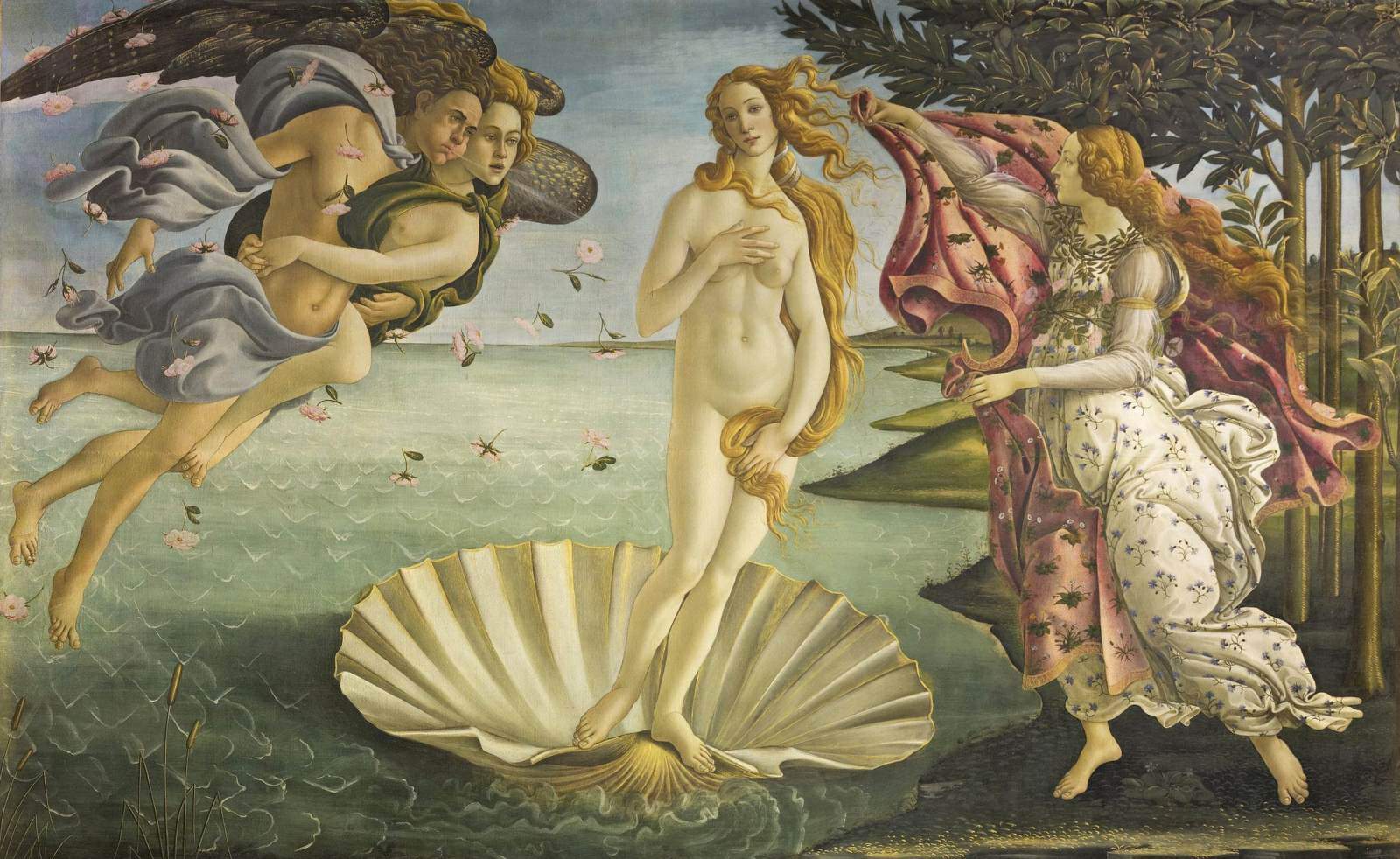

Among the artists, the main person responsible for this intellectual line was Alessandro Filipepi, known to all as Sandro Botticelli (Florence, 1445 - 1510), one of the most illustrious painters of the Laurentian circle: he worked for the Medici for a long time, revisited the ancient mythological repertoire connoting it, thanks also to his collaboration with the literati of the Medici court, with a contemporary and even pedagogical meaning, because the intellectuals at court often had the role of preceptors. Botticelli was the greatest interpreter of Neoplatonism in painting: he was the painter who best knew how to render on canvas that concept of ideal beauty that constituted one of the key-points of Neoplatonic philosophy (the celebrated Birth of Venus, c. 1484, Florence, Uffizi, embodies precisely these ideals).

But other courts also played a very prominent role. Among the most culturally advanced courts of the time, it is worth mentioning the Urbino of Federico da Montefeltro: the latter, a condottiere who had amassed great wealth through his military campaigns, became lord of a town completely on the fringes of the political life of the time, but which, thanks to a shrewd policy of patronage during almost forty years (Federico da Montefeltro ruled Urbino from 1444 to 1482, even managing to obtain, in 1474, the title of duke), was able to make a state among the most culturally advanced. Unlike Florence, however, Urbino lacked a local art school: however, the foundations were laid to create an artistic environment capable of giving birth to two of the greatest geniuses who worked in the following century(Donato Bramante and Raphael were in fact both from the territories of the Duchy of Urbino, and there they were trained).

Federico da Montefeltro’s patronage invested all fields of knowledge: the court of Urbino was frequented by artists, architects, scientists and mathematicians, scholars and men of letters. In the field of letters, Federico da Montefeltro called to his service a humanist like Vespasiano da Bisticci, thanks to whom he succeeded in creating in Urbino one of the richest libraries of the time. Its holdings have now largely flowed into the Vatican Library as a result of the events that saw the Urbino dominions come under the Papal States in the seventeenth century. Urbino was renewed in its urban layout (the remarkable Ducal Palace, a masterpiece of Renaissance architecture, was built, thanks to the work of Maso di Bartolomeo, Luciano Laurana and Francesco di Giorgio Martini) and became a beacon city in the arts, not least because several of the trends of Renaissance art were pioneered here: Indeed, it was in Urbino that Piero della Francesca (Borgo Sansepolcro, c. 1412 - 1492) found fertile ground for his research that sought to combine art and mathematics, partly because it was in Urbino that he could count on the help of mathematicians (such as Luca Pacioli). Federico da Montefeltro was particularly attracted to sciences such as mathematics and geometry, and he gave this direction to Urbino humanism as well. Melozzo da Forlì (Forlì, 1438 - 1494) was also active in Urbino, and Flemish artists (such as Giusto di Gand) who provided not a few suggestions to Italian Renaissance painters found hospitality there. Sandro Botticelli himself also executed some works for the Urbino court.

Following the signing of the Peace of Lodi in 1459, which put an end to disputes in northern Italy, Mantua, too, played a prestigious role among Renaissance courts. Having found social stability as well as a very relevant position in the political logics of the time, Mantua experienced the rule of Marquis Ludovico Gonzaga, who ruled from 1444 to 1478: the marquis wanted to give the city a new face by calling to Mantua two of the leading architects of the time, Luca Fancelli and Leon Battista Alberti (the latter’s Basilica of Sant’Andrea is particularly remembered), and he wanted to celebrate his court by commissioning Andrea Mantegna (Isola di Carturo, 1431 - Mantua, 1506), called to the city just a year after Alberti (in 1460), to do several works including the celebrated Camera Picta, better known as the Bridal Chamber. Mantegna himself was the author of the cycle that best represents the rediscovery of the classical in Mantua and the Gonzaga court’s tendency to want to establish a comparison with the splendors of ancient Rome: the Triumphs of Caesar commissioned in 1485 by Marquis Francesco Gonzaga. The intellectual fervor of the Mantuan court knew no respite and persisted throughout the 16th century as well.

|

| Renaissance and Humanism in Italian Courts. Developments, themes, artists |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.