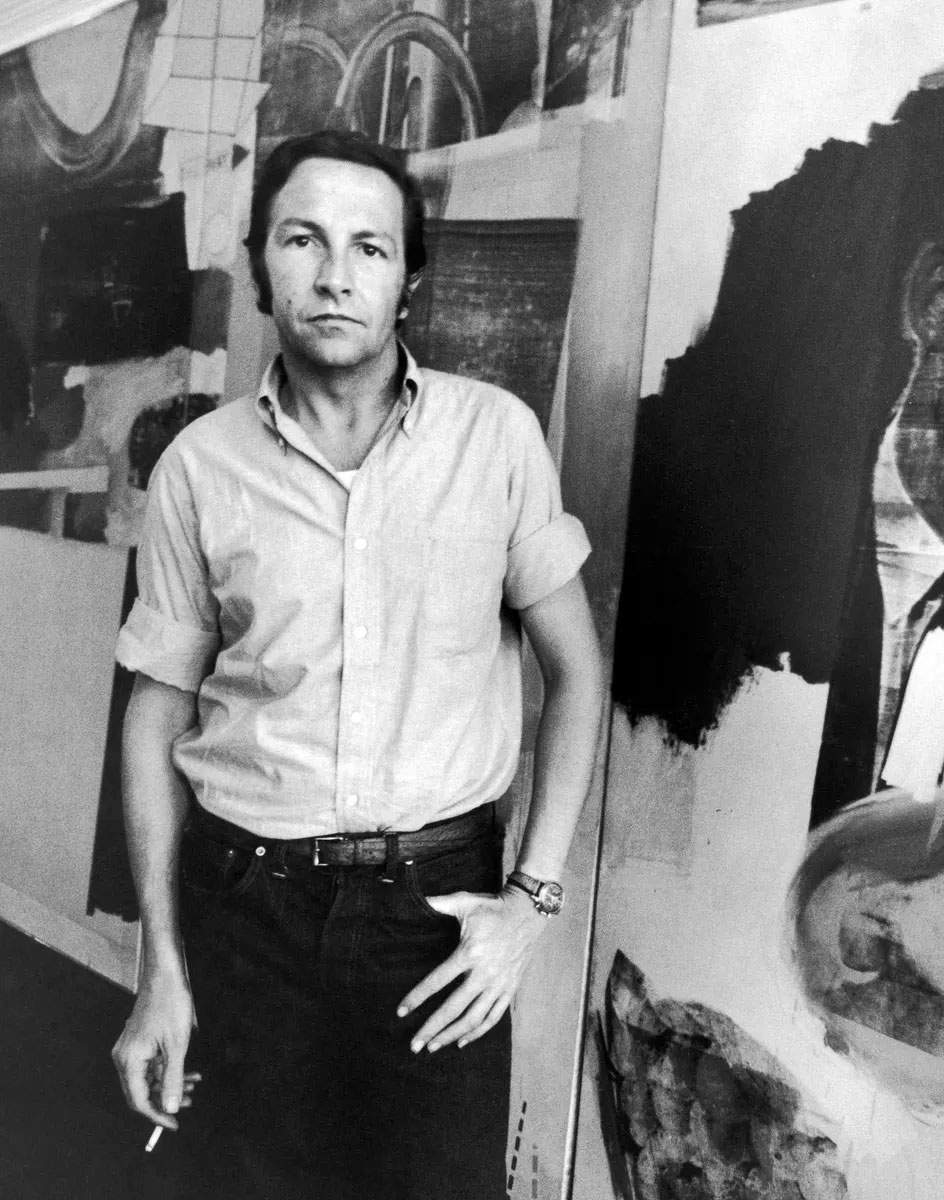

Milton Ernest Rauschenberg, known as Robert (Port Arthur, 1925 - Captiva Island, 2008) was one of the most important artists on the international scene and a member of the New Dada movement. The latter was born in New York, around the figures of avant-garde musician John Cage (Los Angeles, 1912 - New York, 1992) and dancer Merce Cunnigham (Centralia, 1919 - New York, 2009). The two theorists reworked some of the concepts of the Dadaist avant-garde, resulting in works born out of the intermingling of different artistic genres, with the aim of thinning the distance between life and art. However, the substantial difference between the early twentieth-century avant-garde and that of the New Dada group lay in the meaning of their works. Whereas Dadaist Ready Mades, such as Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), were merely decontextualized objects that claimed their artistic nature, New Dada works were transfigured by the author’s intervention with references topersonal experience.

Rauschenberg fit fully within the movement of Cage and Cunnigham by making works that were fragments of life. Throughout his career, the Texas artist was not limited solely to traditional techniques, but also experimented with more unusual ones, often combining them in order to increase his artistic possibilities. Finally, Robert was also very attentive to various social issues, such as protecting the environment and criticizing the consumerist system.

Robert Rauschenberg was born out of the marriage of Dora Carolina Matson and Ernest R. Rauschenberg. At age 16, the young man entered pharmacy college and in 1943 was called to arms by the U.S. Navy, where he served as a technician at the psychiatric hospital until 1945. Rauschenberg enrolled at the Kansas City Art Institute and later at theJulian Academy in Paris, where he met his future wife Susan Weil (New York, 1930). The latter convinced him to enroll at the Black Mountain Collage, where Josef Albers (Bottrop, 1888 - New Haven, 1976), one of the founders of the Bauhaus, a famous German art institute closed in the 1930s by the Nazis, had become a professor of painting. However, the relationship between Albers and Robert was not the best, as the young student was not compatible with the painting professor’s rigid teaching method.

In the same year Rauschenberg met avant-garde composer John Cage (Los Angeles, 1912 - New York, 1992), with whom he established a deep friendship that gave rise to several collaborations. In fact, the musician was one of the first to believe in the young artist and welcomed him into the New Dada movement he founded. The meeting with Cage constituted a turning point in Robert’s career, as the musician brought him closer to a more conceptual and performative approach to art. During these years, Rauschenberg developed his early works that foreshadowed the characteristics and themes of his mature masterpieces. Even at that time, the artist was not limited to the use of a single technique, but experimented with several, sometimes combining them together. Moreover, even in these early projects were present certain fundamental concepts that he would carry through his entire career, such as doubling, repetition, and grids.

In 1949, Robert Rauschenberg moved to New York, where he came into contact withAbstract Expressionism, an artistic current born in the 1930s whose major exponents were Jackson Pollock (Cody, 1912 - Long Island, 1956) and Mark Rothko (Daugavpils, 1903 - New York, 1970). Following the discovery of this current, Rauschenberg began to merge his style with vigorous expressionist brushstrokes and abstract symbols.

In the years that followed, Robert embarked on a tour of Europe and North Africa, during which he began to combine paintings, sculptures, and objects of all kinds to create a single work. These projects were important for the future development of theCombines series (1954-1964), Rauschenberg’s most important works. Indeed, already discernible in these collages was the young American’s intent to diminish the distance between art and everyday life.

In 1963 the artist’s first solo exhibition was organized at the Jewish Museum in New York, and the following year Rauschenberg consolidated his fame by winning the Grand Prize for painting at the Venice Biennale. At the exhibition Robert presented his Combines for the first time, which were a huge success.

Later, Rauschenberg became interested in the technological world and began a series of collaborations with engineers and physicists to create works of art. This research flowed into the E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology), an organization that brought together artists and engineers to form collaborations, uniting the two fields of knowledge.

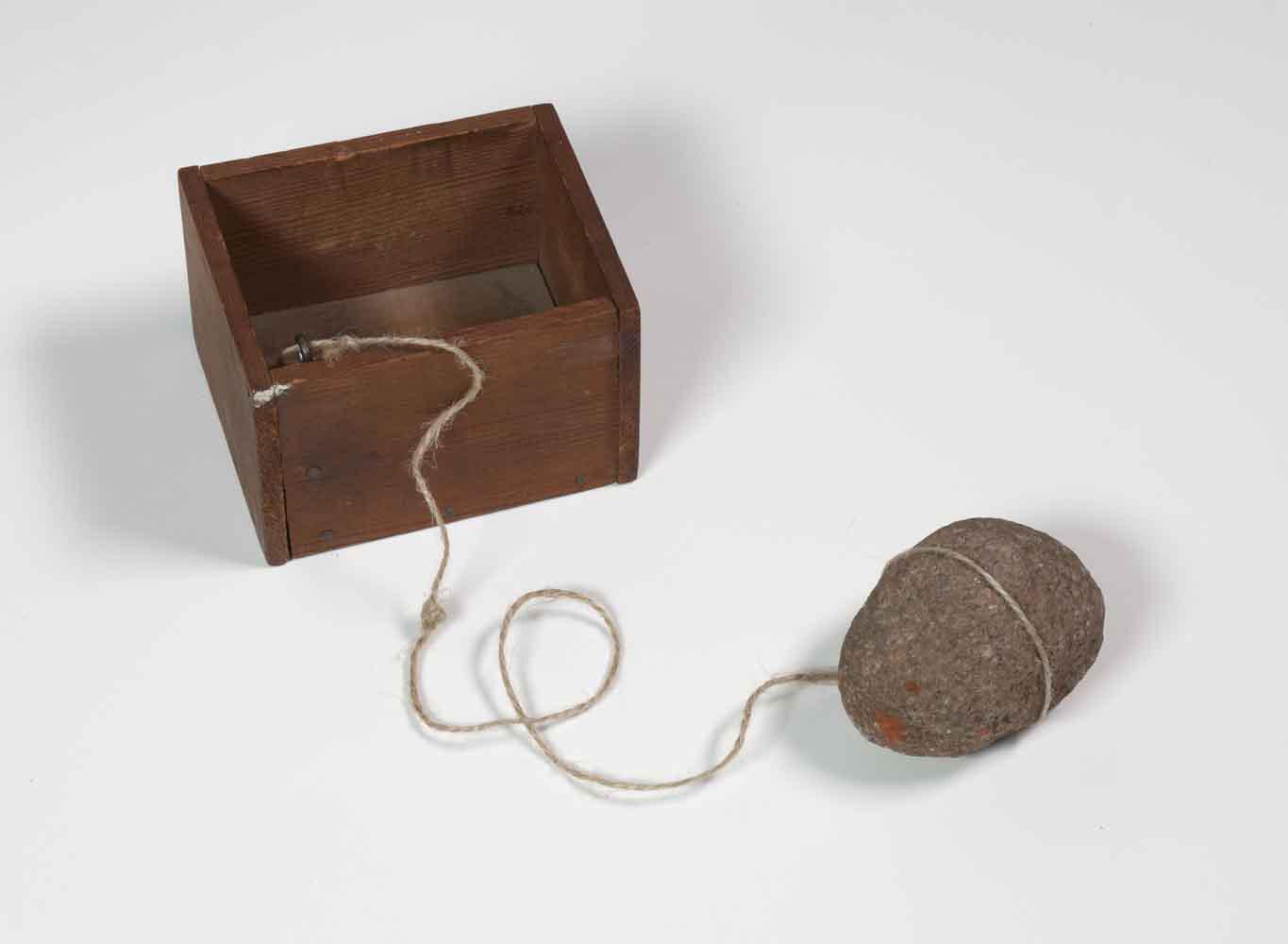

Another very important artistic field was performance art, as Robert designed costumes and sets for various performances. However, the American did not limit himself solely to working behind the scenes, but also devised numerous performance arts. In some cases he himself brought the performances to life, in others he integrated his works with performative aspects, such as sound in the Elemental Sculpture series (1953-1959) or the passage of time in a Combine.

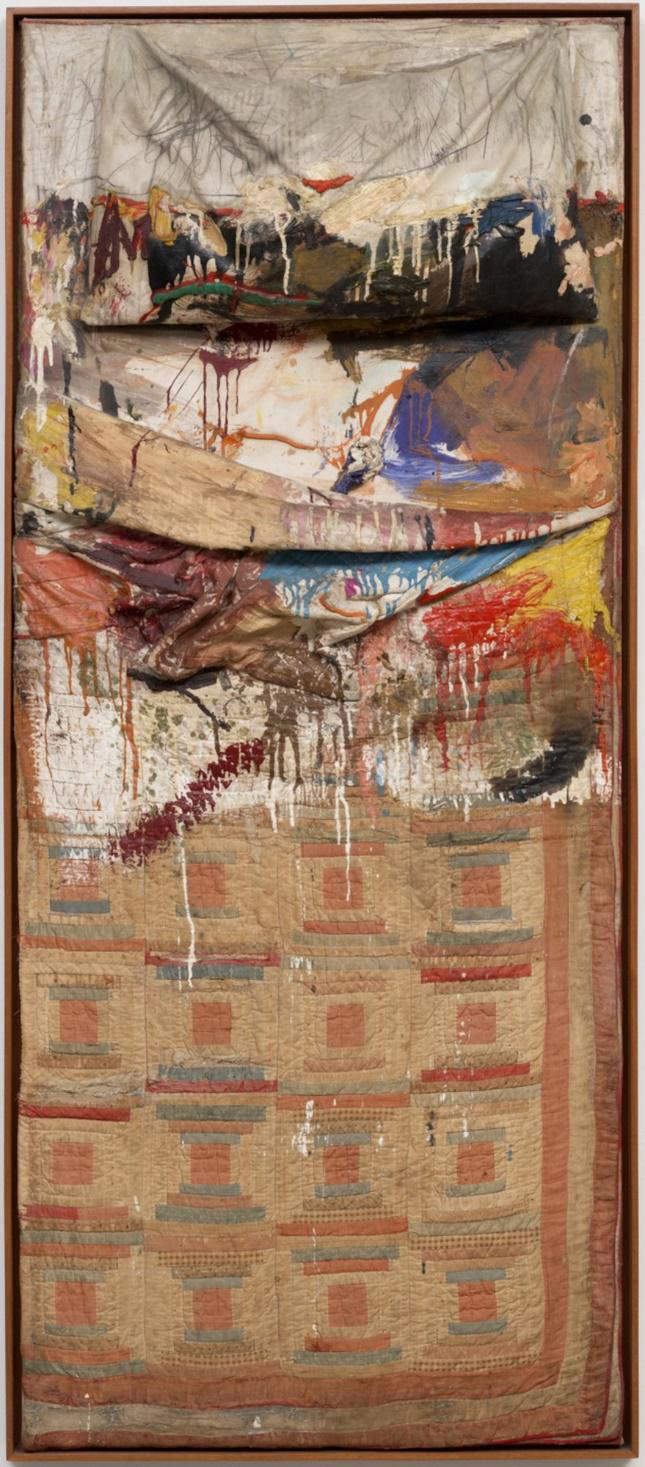

Robert Rauschenberg in 1970 moved to Captiva Island, a small fishing village on the Florida coast, diametrically opposed to chaotic New York City. In this little earthly paradise the artist was able to rediscover a new vitality, which influenced his works by lightening his colors and prompting him to use natural materials. The move to Captiva Island gave birth to the most fruitful period of Robert’s career, which devised several masterpieces between the 1970s and the 1990s. The work executed on Captiva Island can be seen in works such as the Venetians (1972-1973) and in Mirage (1975), in which Rauschenberg expressed his passion for found materials and the study of different types of textiles. In addition, during his stay on the small island, Robert deepened his interest in environmental issues, which became central to a new long-term project, Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange, known as ROCI (1984-1991).

Even in the final years of his career, Robert Rauschenberg continued to experiment with new technologies and materials with the same enthusiasm as in his early artistic pursuits. In 1996, a retrospective exhibition of his work was organized by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, thanks to which Robert was able to trace his entire career. Although Rauschenberg had a paralyzed right hand due to a heart attack in 2002, he continued to work using only his left hand until 2008, when he died of cardiac arrest in the hospital.

It is impossible to enclose Robert Rauschenberg’s works within a canonical style or genre, because from his earliest works the Texas-based artist began experimenting with different techniques and different types of media. Moreover, his works almost always go beyond the contemplative, identifying themselves as objects that live and interact with the viewer’s space.

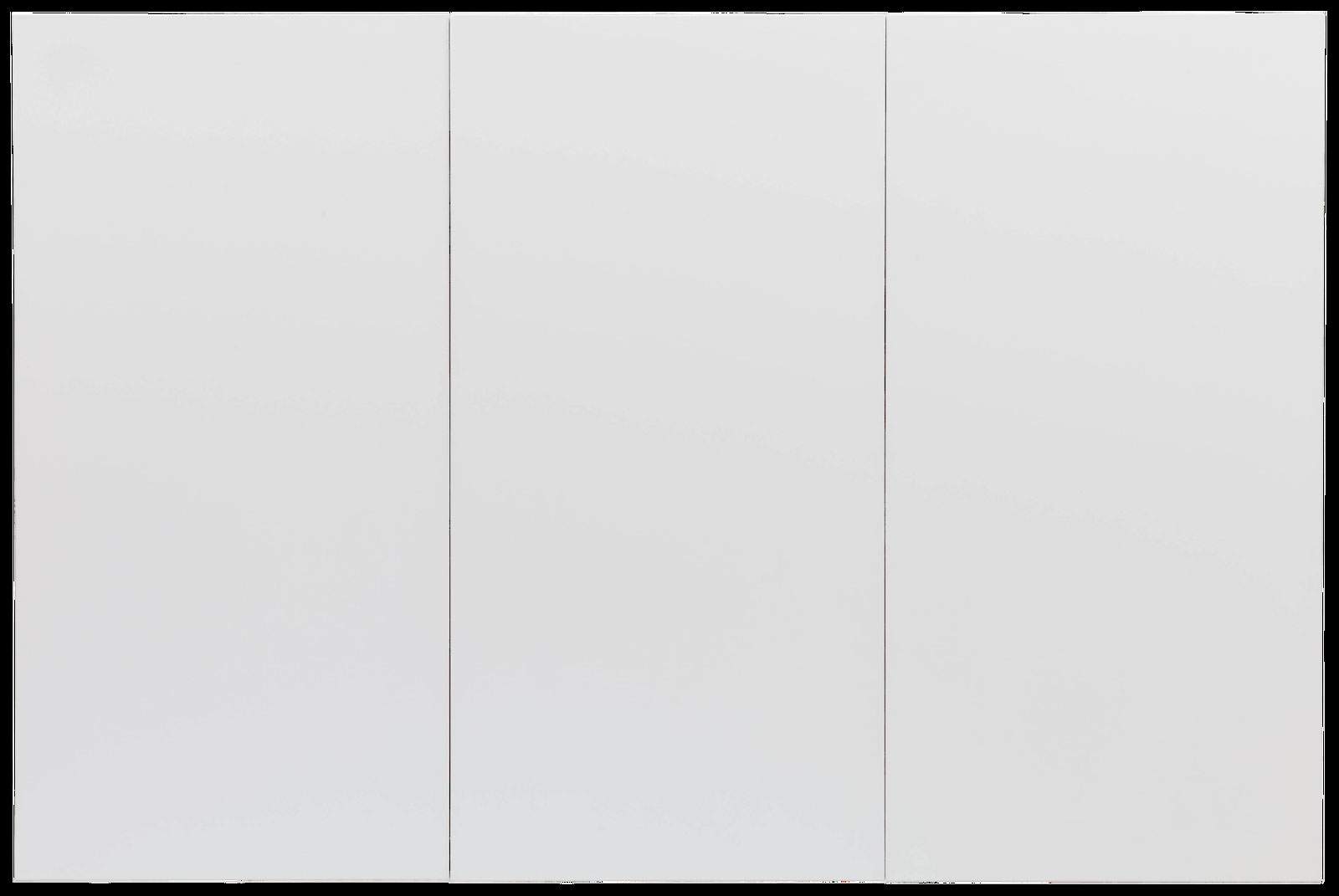

One of Robert Rauschenberg’s earliest works were the White paintings (1951), monochromatic white paintings arranged in grids. The panels Robert developed had no aesthetic characteristics, but were only realized once they made contact with the viewers. The White paintings were like works that were not fully realized, needing theactive intervention of the viewer to be able to fully express their essence. In fact, the artist had thought of the panels as blank canvases, which were not limited to a single subject, but to endless possibilities that imprinted themselves on the canvas every time someone or something passed by.

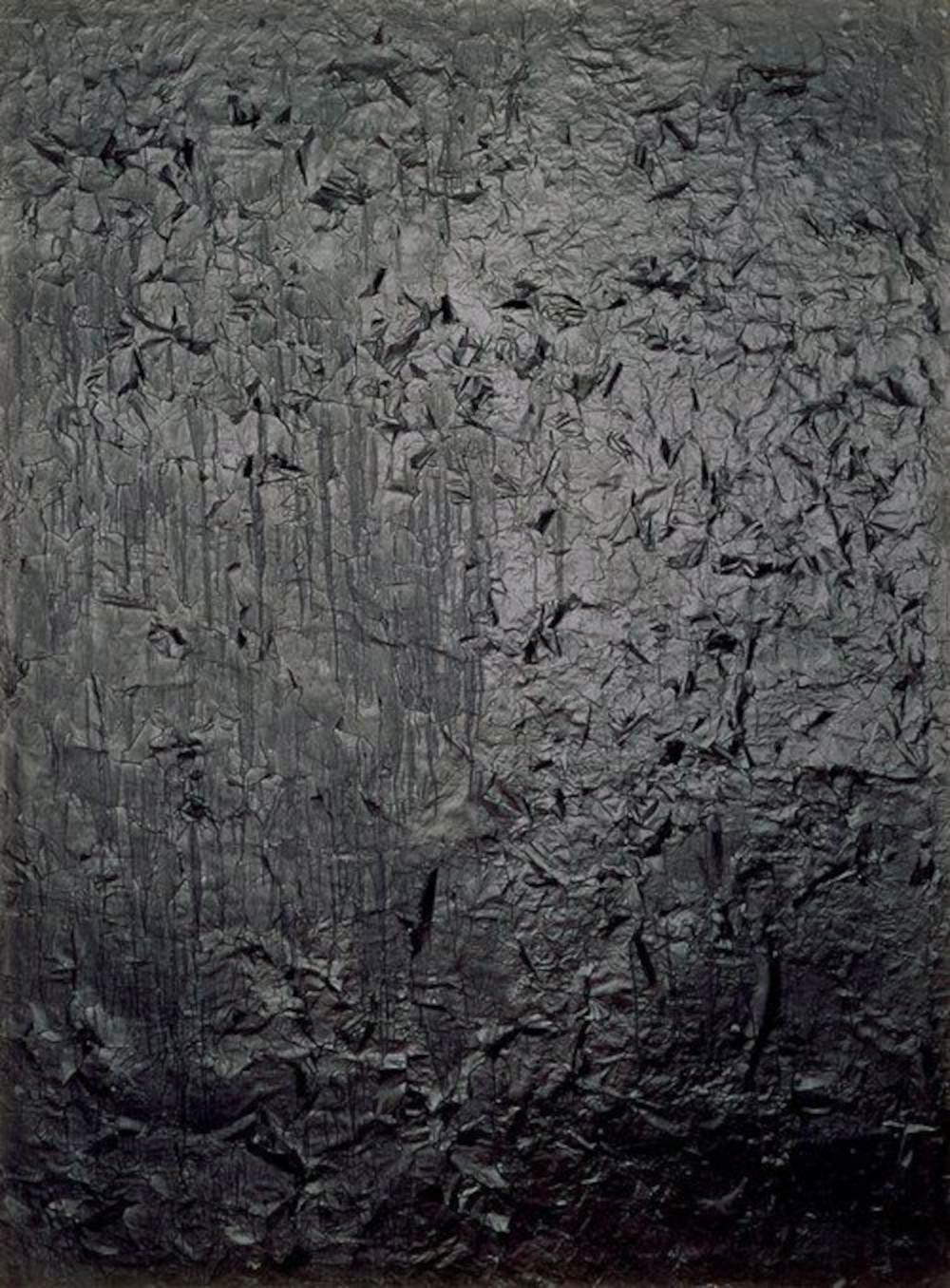

In the same year Robert developed the Black paintings (1951), or monochrome panels, which compared to the White paintings differed in their black color and texture. In fact, these paintings were made with the addition of newspaper sheets, which depending on the angle could be glimpsed by the viewer. In this way, Rauschenberg inserted for the first time the element of surprise, which would become fundamental in the elaboration of his most important works: the Combines. Further works in the monochromatic series were the Red paintings (1953-1954), monochromatic red paintings made by adding different materials, such as wood, newspaper sheets and many others.

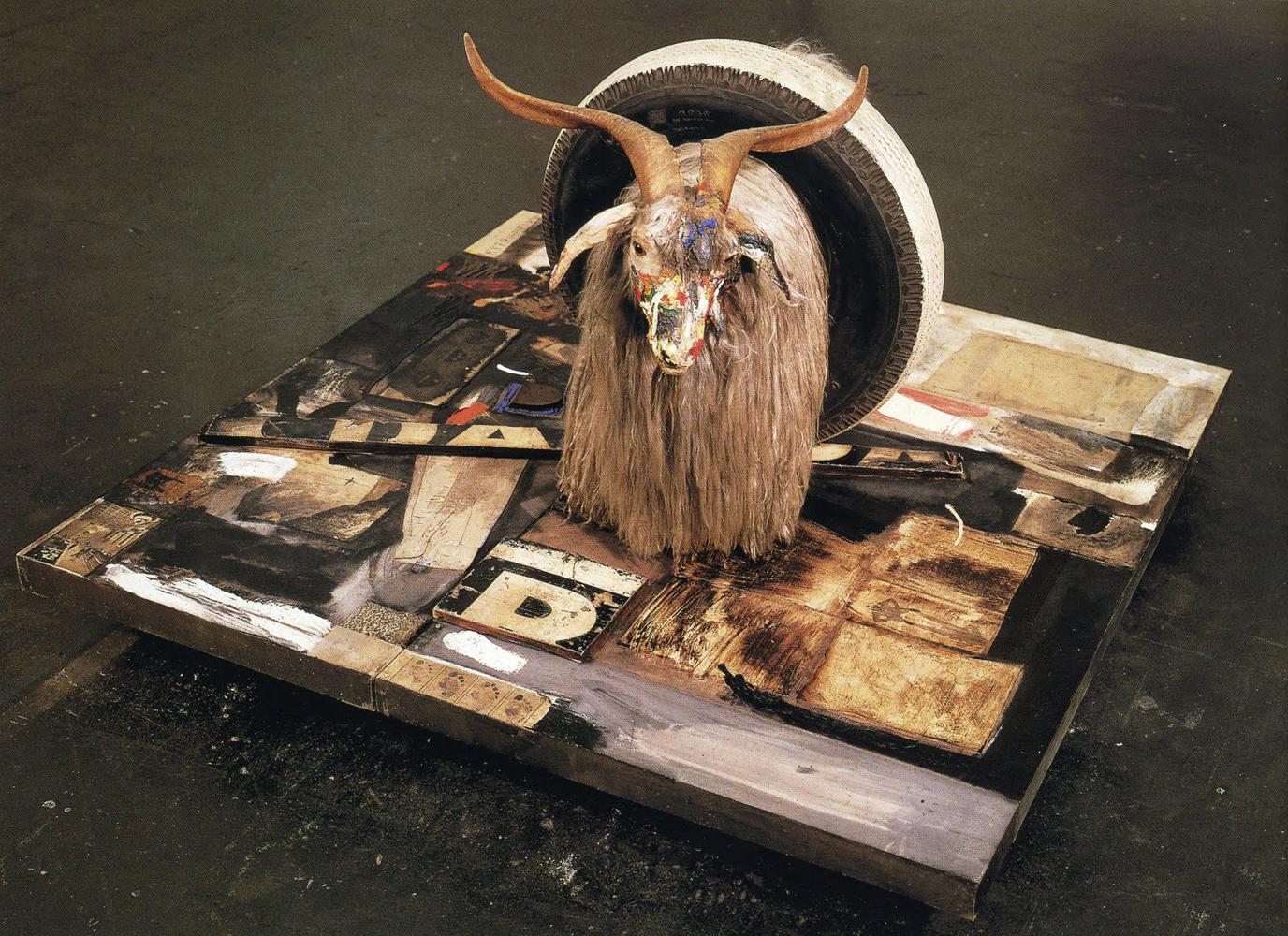

Around 1954 Robert Rauschenberg invented the term Combines to describe his latest works: combinations of painting and sculpture that went far beyond the usual artistic categories. In fact, the Combines series included very different works: some were hung on the wall, others stood alone, and the materials used changed from work to work. The artist began collecting objects on the street, in dumps and in all kinds of stores and then assembling and treating them together. Through this process Rauschenberg was able to give a new life to objects discarded by society: on the one hand elevating them to the status of works of art, and on the other using their effect of estrangement and surprise. The latter was caused by the presence of unusual elements, because they were discarded by society, within the artistic context, hitherto exclusive of works of high intellectual and aesthetic value.

Among the most famous Combines are Bed (1955) and Monogram (1955-1959). In the former, Robert Rauschenberg hung a bed on a wall and painted it like a picture, with brushstrokes very similar to those of abstract expressionist painters. Through this object Rauschenberg succeeded in transporting the artist’s intimate dimension before the viewer’s eyes, since the bed constitutes the place where the main stages of every human being’s life take place.

In Bed the surprise effect is achieved through the substitution of the canvas for a bed, but it is in Monogram that estrangement is perfectly achieved by Rauschenberg. In fact, the viewer is confronted with a stuffed goat resting on a canvas stretched out on the floor, similar to those of Jackson Pollock. In an interview, Rauschenberg explained that the work had no polemical intent, but was intended to surprise the viewer. In this case, the effect of estrangement is achieved through the presence of a now-dead living being, which acquires new life, thanks to its elevation to an art object.

Between 1984 and 1991 Rauschenberg worked on a large-scale art project, Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (ROCI). For the realization of ROCI, Robert traveled all over the world to initiate an exchange of knowledge and experience that would lead to the creation of works of art, the result of different cultural influences. Rauschenberg’s aim was to create a dialogue between different cultures and give voice to countries where artistic manifestations were repressed by economic or political situations.

Among the most important projects was ROCI Chile (1985), during which Robert visited the Antofagasta copper mine in Chile, where local artist Benito Rojo explained to him how to use matting agents on copper. The result of this experience was a collection of paintings made on a screen-printed photographic medium and the Copperhead series, a total of fifteen paintings on copper (1985-1996). In addition, this experience allowed Rauschenberg to learn about and bring back to his homeland the consequences of dictator Augusto Pinochet’s repressive regime on the Chilean population, which had instead been concealed and masked in the United States.

Robert Rauschenberg was one of the greatest innovators in the contemporary art world, and his contribution was instrumental in moving beyond the classical categorization of art genres.

Most of Robert Rauschenberg’s masterpieces are preserved in the many American museums. A substantial portion of his works are owned by the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation (RRF ), established at the behest of the artist himself in 1990, with the aim of funding emerging young artists and advancing the social and political battles Rauschenberg led throughout his life. In addition, several of the artist’s works are scattered throughout New York’s many museums, for example, The Museum of Modern Art and The Whitney Museum of American Art. On the other hand, galleries in Los Angeles and San Francisco can also boast an important consistency of the Texas artist’s works, such as the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Eli and Edythe L. Broad Collection and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

However, some of Rauschenberg’s works are also individually located in numerous European museums of contemporary art, for example The Moderna Museet in Stockholm, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, and even at the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf.

|

| Robert Rauschenberg, life and works of the New Dada artist |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.