Surrealism was a European avant-garde literary and artistic movement that arose in Paris in the 1920s and spread internationally until the outbreak of World War II, covering everything from literature to painting, sculpture and photography to theater and film. As with other historical avant-gardes at the turn of the century, the movement’s intentions were introduced by literati, even before visual artists, in the journal Littérature founded by André Breton (Tinchebray, 1896 - Paris, 1966), Louis Aragon (Paris, 1897 - 1982) and Philippe Soupault (Chaville, 1897 - Paris, 1990). This group of intellectuals, after initially joining the Dadaism movement and supporting its spirit of subverting traditional art categories, techniques and modes of enjoyment, began to take an interest in the themes of the irrational and the unconscious, which were becoming more widespread in those years thanks to the discoveries of the founder of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud.

The first manifesto of Surrealism was published in 1924 by the poet and art critic Breton himself, who up to that point had been a member and leader of the Dadaists in France, and after whom many among them joined the new movement. In the Manifeste du Surréalisme were expressed the premises, later found to be very influential in the rest of Europe and spread to other continents from America to Japan, that there was a need for a liberation of the imagination of the artist who could thus, as opposed to the realm of logic, lower himself and promote his own spontaneous, accidental, dreamlike dimension, the one analyzed by Freud himself in his patients. With the rise of the latter’s theories on the inner life and sexuality, the dynamics of the dream came to represent the ideal state for creation, as the meeting point between conscious rationality and the irrationality of unconscious elements and hidden desires. At the foundation of the movement was the exaltation of “pure psychic automatism,” which guaranteed for any art form that unusual combinations could be created without aesthetic or moral concerns, practicing associations between ideas and images in a fortuitous, automatic, liberating way. Surrealism aspired to change lifestyles, to transform human beings’ relationships with themselves and others.

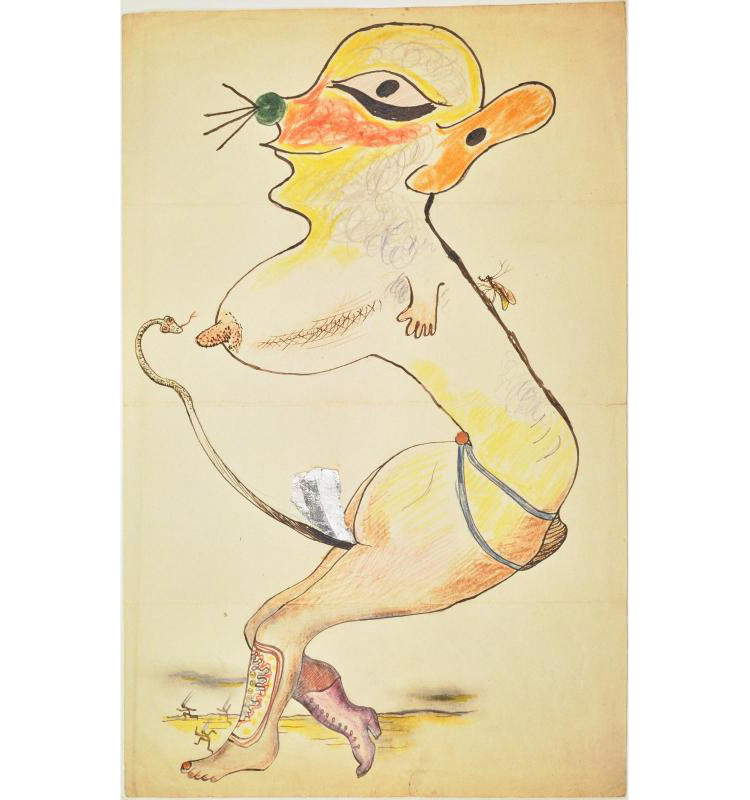

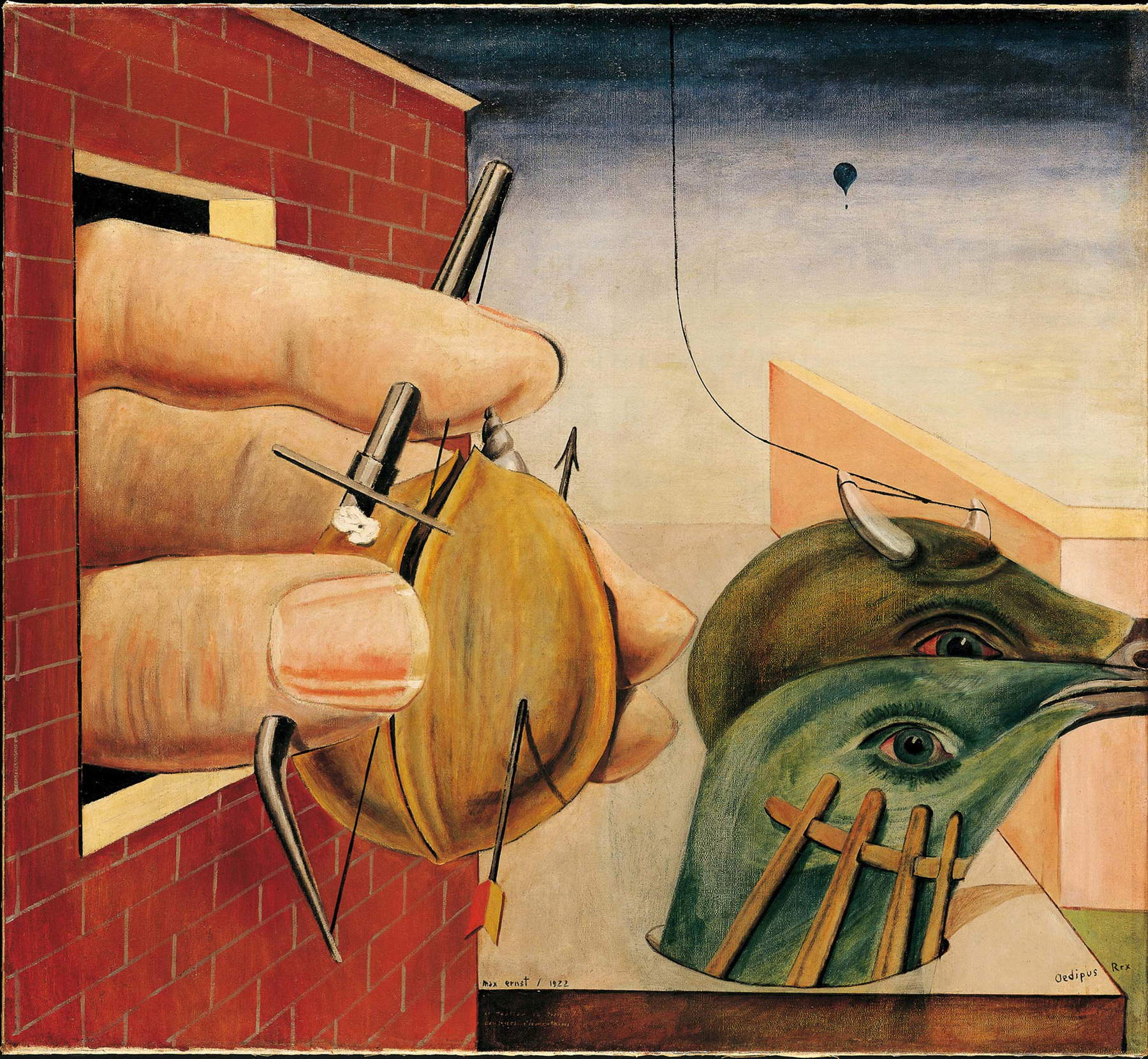

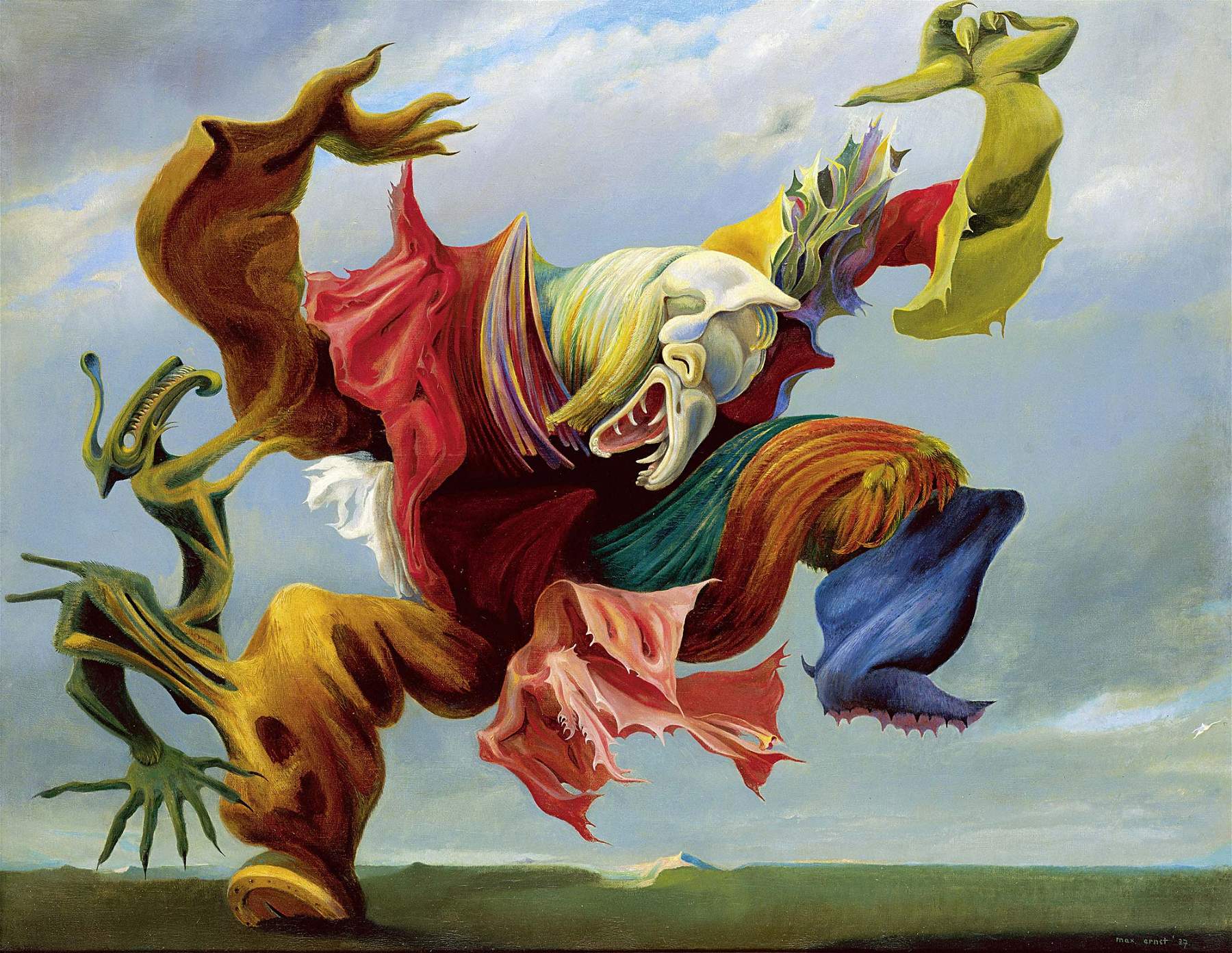

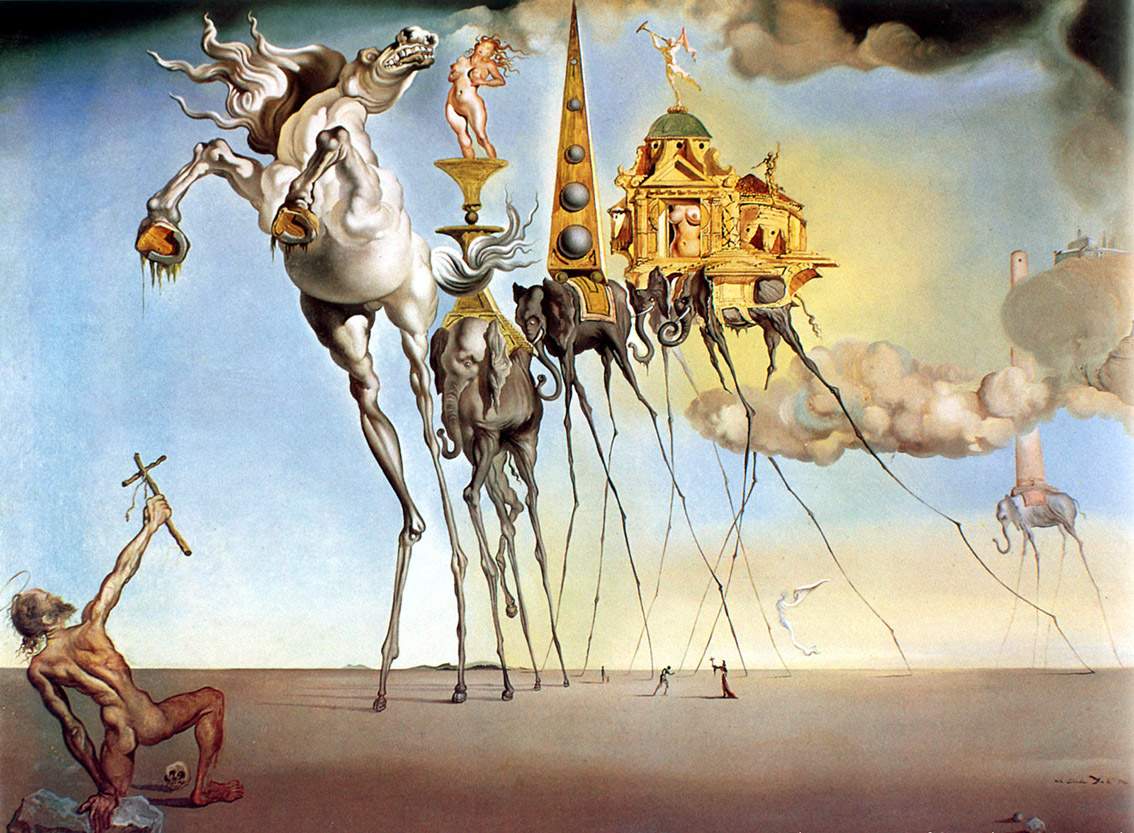

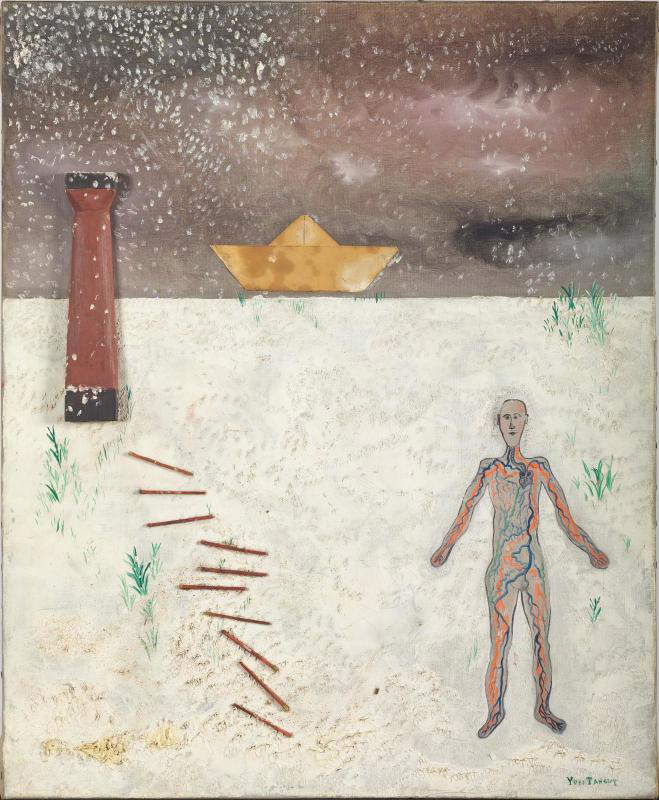

Leading exponents included Frenchmen André Masson (Balagny-sur-Thérain, 1896 - Paris, 1987), Hans Arp (Strasbourg, 1886 - Basel, 1966), Yves Tanguy (Paris, 1900 - Woodbury, 1955), German Max Ernst (Brühl, 1891 - Paris, 1976), Spaniards Joan Miró (Barcelona, 1893 - Palma de Mallorca, 1983) and Salvator Dalí (Figueres, 1904 -1989), the Belgians René Magritte (Lessines, 1898 - Brussels, 1967) and Paul Delvaux (Antheit, 1897 - Furnes, 1994), the Americans Man Ray (Philadelphia, 1890 - Paris, 1976) and Alexander Calder (Lawnton, 1898 - New York, 1976) and, among others, the Swiss Alberto Giacometti (Borgonovo di Stampa, 1901 - Chur, 1966).

It can for all intents and purposes be considered the experience of Dadaism, which disrupted the conventions of secular traditional art from 1916, the precursor of Surrealism. The Surrealist movement began from a literary group that emerged from the very Dada movement in Paris, when the enthusiasm of adherent André Breton clashed with the positions of Swiss Dadaist founder Tristan Tzara. Between 1919 and 1922, the need to revolutionize French and world society politically as well took hold among them, writers and artists alike.

Surrealism, intended to oppose Dadaist art, linked to the dramatic historical moment experienced in Europe during the years of World War I, with a reconstruction that exalted human interiority and freedom of expression. Alongside Dadaism in the same years, equally decisive was the spread of Giorgio De Chirico ’s Metaphysical painting , which influenced many artists in conceiving works with suspended atmospheres, surreal in fact, to grasp a supra-reality beyond the sensible appearance. Individual subjects and objects of the imagination could tie together even without logical connections, and in settings that were not necessarily verisimilar.

The Surrealists, from the earliest hour, promoted “the coupling of realities, apparently irreconcilable, on a plane that is apparently not convenient to them.” Breton, the first animator of Surrealism, officially founded the movement in 1924 when he wrote its manifesto, which stated that Surrealism is a “Pure psychic automatism, through which one proposes to express, by words or writing or otherwise, the real functioning of thought. Command of thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, outside of all aesthetic and moral concerns.” However, the term surréalisme had already been used, for the first time in 1917, by the poet and playwright Guillaume Apollinaire.

The movement had its origins with the journal Littérature in which matured the energies that later gave birth to La Révolution Surréaliste, the official organ of the group from 1924 until 1929, in which in addition to discussing writing there was an interest in works by de Chirico, Max Ernst, André Masson and Man Ray, among others, whose reproductions were in this way widely circulated. In the following years along with other publications, the first nucleus of Surrealism nurtured a considerable stream of theoretical and literary production, concerned with explaining the reasons for its ethical positions and aesthetic choices albeit amid differences, dissent and approaches between one and another artist.

The Bureau des recherches surréalistes had also been founded in 1924. Alongside the poets gathered around Breton converged in Paris painters from different backgrounds who each contributed in their own way to the Surrealist revolution, at least for a fortnight until World War II. As early as January 1925, the Bureau officially published its revolutionary intent, which was signed by 27 participants, including Breton, Ernst and Masson themselves.

The purpose of their research was to “collect all possible information concerning forms that could express the unconscious activity of the mind.” Sigmund Freud ’s scientific work had been deeply influential, particularly his 1899 essay The Interpretation of Dreams. The psychoanalyst Freud had legitimized the importance of dreams and the unconscious as valid revelations of human emotions and desires; analyses of the complex and repressed inner world of sexuality, desire and aggression provided a theoretical basis for much of the Surrealist artists.

In literature they experimented with “automatic writing without rational control or preconceived ideas, in a semi-hypnotic state, writing tirelessly and making unusual associations surface, of great beauty”; this technique was transposed to the visual and plastic arts, and the Surrealist style was divided between those who practiced “automatic” drawing and painting, and those who painted or created sculpture following their own more defined, figurative style. This more meticulous undercurrent was aimed at bringing out a powerful inner vision, while still passing through a control of techniques and mechanisms of thought. An important double flowering of Surrealist art ensued. Then, in 1926, the Galérie Surréaliste was opened in Paris .

The spread of the magazines and the continuous exchanges with Paris allowed artists in the Western world, whether isolated or united in other groups, to proclaim themselves “surrealists.” The second phase of the movement, from about 1929, had coincided with Salvator Dalí’s membership, and with Breton and many others joining the French Communist Party, wishing to contribute actively to realizing the communist political dream. With the second manifesto of Surrealism in 1930 and the journal Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution from 1930 to 1933, the project of liberation was further defined, both creatively and socially, and the need for an “absolute revolt” against the established order.

In those years, the success of Surrealism is evidenced by the exhibitions in London and New York in 1936 and especially the major international exhibition at the Galerie des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1938. However, while not halting the cultural influence of their ideas even in post-World War II art, under wartime pressures around 1939 the members of the original movement dispersed; with the outbreak of war and the German invasion of France their political stance made them invisible to the Nazi dictatorship, forcing them to isolate themselves or flee to different countries.

The Surrealists sought to channel the unconscious to reveal the power of the personal imagination, heirs to the tradition of nineteenth-century Romanticism also in their interest in myth and primitivism. But unlike all their predecessors, these artists active in the mid-twentieth century believed in symbolic revelations of the unconscious, captured from everyday life and made to flow into a free and liberating poetics of nonmeaning . The early Parisian Surrealists used art as a respite from violent political situations and to address the unease they felt about societal uncertainties, employing fantasy and dreamlike imagery to generate works in a wide variety of media. As mentioned, André Breton had defined Surrealism as an expression of the actual functioning of thought, by means of the written word, and in any other way. Expressively, it was not a homogeneous group responding to a single program, and it did not produce a new univocal way of painting, photography, or sculpture.

In Surrealist painting there were at least two different attitudes among the artists, one part drew from subjects and objects of reality, although depriving them of logical and usual references (as is the case in dreams), and another part reached the limits of abstraction by instinctive and automatic means. Recurrent motifs and favorite themes can be identified of each artist, which emerged through the mechanism of unconscious free associations. Nature is a frequent scenario and animals often present, in Max Ernst for example birds, in Salvador Dalí ants or eggs, in Joan Miró biomorphic figures. It is the extravagance and ambiguity of the imagery that applies to all to shake the viewer out of a comforting attribution of meaning.

Some painters, just like Ernst and Tanguy, Magritte, Delvaux and Dalí, chose to decontextualize recognizable elements to combine them together in their images, where reality was deformed or entirely reinvented, and where the use of academic painting practice was in the service of a personal magical vision(read an in-depth study on Surrealism and magic here); others like Masson and later Miró, aimed at a genuine psychic improvisation for an innovative abstraction of forms, through color. Color decisive for all, used in monochrome or saturated and varied compositions to convey a dreamy state, beyond the possible visual conditions.

In common among them was the use of various other techniques to create novel visual compositions, including collage, decalcomania, and for drawing, grattage and especially frottage: by placing a sheet of paper or canvas on a raised surface of wood or other material, and rubbing it with a pencil, a relatively random visual transposition of the object was obtained; the final image could be retouched or completed in various ways by the artist.

Hyperrealism and automatism were not mutually exclusive. Miró, for example, often used both methods in a single work. But however the subject matter of the work was represented, it always tended toward a bizarre and illogical visual result. Under the initial stimulus of Miró and Ernst matured the style of Tanguy, in whose paintings no real content is discernible, and which marks the transition from automatism to the surreal image construction of the 1940s.

Magritte’s work was characterized by the unpredictable juxtaposition of realistic and familiar elements, arranged, however, by twisting their usual relationships into ambiguous and mysterious atmospheres.

Because of his extravagant personality, Salvador Dalí was, and continues to be considered the quintessential ’character’ of Surrealism since he joined it in 1929. Dalí’s painted pictures aroused great interest in the French capital, as he also executed interesting objects of symbolic functioning and wrote poems and critical texts aimed at clarifying his paranoid-critical method, based on combining Freudian psychoanalysis with the pictorial examples of some of his colleagues. The evolution toward an “objective materialization of delirium” that characterizes Surrealism had in him one of its greatest protagonists.

A number of Surrealists are known for three-dimensional objects and sculptures. The goal was the displacement of the object from its intended context, normal circumstances and a temporal narrative, interpreted beyond cultural attributes and below the surface of reality. Hans Arp, for example, was known for his assemblages and Concretions, while Giacometti leaned toward more traditional sculptural forms, many of them hybrid figures.

Similarly, photography, because of the ease with which it allowed artists to produce alienating images, occupied the role of a central tool. Among others, Man Ray used the medium to explore automatic writing with light, avoiding the camera altogether. Other photographers using rotation or distortion rendered unusual shots, shots constructed to appreciate a new reality not evident except through the artist’s gaze, gradually achieving abstract results.

The enthusiasm for film then was largely due to the possibility that camera movements offered to depict the changing and unpredictable nature of inner consciousness. A visual art “in motion” is the idea from which also stemmed the interest aroused by the sculptures of Alexander Calder, maker of ingeniously animated aerial toys. The articulated imagery of the Surrealists, populated with extravagant, disturbing at times bewildering presences, is probably the aspect of movement that is most recognizable, but also the most elusive to classify and define.

|

| Surrealism. Origins, styles and main exponents of the avant-garde movement |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.