Tamara de Lempicka, born Maria Gurwik-Górska (Warsaw, 1898 - Cuernavaca, 1980), was a Polish painter, an icon of the glittering, unbridled luxuries of the 1920s in Paris, where she landed from St. Petersburg fleeing Russian revolutionary uprisings: in France, De Lempicka adhered to the Art Deco style and brought to the canvas characters from her everyday life adorned with the latest fashionable clothes and expensive jewelry.

The uniqueness of her works lies in the combination of these modern elements with a style that recalls the hieraticity and plasticity of ancient statues. His powerful figures are made with clean, sharp lines, and the colors are vivid but applied with flat, compact brushstrokes that enhance the volumetries.

Toward the 1940s, coinciding with the outbreak of World War II, de Lempicka changed themes and styles of her painting, veering toward religious and humanitarian themes, often failing to meet with critical acclaim, which nevertheless rediscovered her late in life in the 1970s.

Today De Lempicka’s works are admired and appreciated for their modernity and elegance, and it is not uncommon to see them used in different contexts. For example, a great admirer of hers is singer Madonna, who has often been inspired by de Lempicka’s works for her looks and shown them on tours.

Tamara de Lempicka was born Maria Gurwik-Górska in Warsaw on May 16, 1898, to a Polish mother, Malvina Decler, and a father of Russian nationality, Boris Gurwik-Górski, a wealthy Jew who nevertheless abandoned his family when the artist was a child. A very important figure in the artist’s growth was her grandmother Clementine, who took care of her and enabled her to be able to attend prestigious educational institutions, such as the Polish College in Rydzyna or the Villa Claire school in Lausanne, Switzerland. Her grandmother was also a point of reference for De Lempicka’s cultural education: in fact, the two of them took a trip to Italy that proved crucial. When her grandmother passed away in 1907, De Lempicka moved to St. Petersburg. In the meantime, already around the age of 10, De Lempicka had begun to use watercolors and become interested in art.

In St. Petersburg, in 1916, the artist married a young lawyer named Tadeusz Lempicki, and it is from him that she derives the surname by which she is known. In the same year, a baby girl named Kizette, who appears in some of the artist’s works, was born of the union. Meanwhile, riots related to the Russian Revolution broke out in the city, so the couple moved to Paris in 1918, and here de Lempicka began working as a hat designer in order to support herself. She managed to enroll in painting classes at the Académie de la Grande Chaumiere and the Académie Ranson, where she had the artists Maurice Denis and André Lhote as her teachers. She quickly achieved good success, and began exhibiting publicly for the first time in 1922 at the Salon d’Automne, and then participated in major exhibitions in Paris.

In the following years, Tamara de Lempicka became a landmark of artistic, as well as social, life in Paris. The artist, aware of her success, began to build up a sort of persona devoted to the wild amusements that the French city offered in those years, so as to increase her popularity. He also indulged publicly in passionate affairs with women, who later appeared in some of his works. He went to Italy again in 1925, with the intention of studying the works of classicism. During a stay in Milan he had the opportunity to mount his own exhibition at the Bottega di Poesia gallery.

Also in Italy she met Gabriele d’Annunzio, whose portrait she painted, and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, who helped introduce her painting to the country. In 1928 Tamara de Lempicka separated from her husband and began a new relationship with Baron Raoul Kuffner de Diószegh, to whom she later remarried in 1933. After numerous trips around Europe, at the beginning of World War II De Lempicka settled with her family in the United States, specifically in Beverly Hills, California. This new life overseas coincided, however, with an existential crisis for the artist, which led her to engage in humanitarian and solidarity activities.

In the United States, de Lempicka was featured in several exhibitions and galleries between New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco. A period of artistic inactivity followed, which lasted until 1957. In that year, de Lempicka exhibited unpublished works at the Sagittarius Gallery in Rome, which were, however, received unfavorably by critics. Meanwhile, in 1962 her second husband died, so De Lempicka moved to Houston, Texas, where her daughter had meanwhile settled. In 1969 she returned again to Paris and resumed painting, achieving renewed success with a 1972 anthological exhibition at the Galerie du Luxembourg. In 1978 Tamara de Lempicka moved to Cuernavaca, Mexico. There she died on March 18, 1980, and her ashes were scattered on the crater of the Popocatépetl volcano, as per the artist’s request.

Tamara de Lempicka’s paintings are deeply connected with her lifestyle, rendering a glittering image of the 1920s in Paris. In particular, her portraits in full Art Deco style of various personalities of the Parisian aristocracy and upper middle class, including men in elegant suits and women covered in jewelry and adorned with hats, gloves and voluptuous scarves, were very famous. There is no shortage of the status symbols most in vogue at the time, such as automobiles, luxurious destinations like Saint Moritz and the New York skyline. Luxury and opulence were also often accompanied by sensuality and glamour, which permeated Tamara de Lempicka’s works to the point of veering toward eroticism. Mostly, women with a melancholy and unattainable air, haughty and in provocative attitudes, appeared as protagonists in the paintings. The scenes were constructed with clean lines and vivid colors spread in compact brushstrokes, which went to accentuate the plasticity of the forms. De Lempicka did not use many color tones; in fact, more or less the same colors recur in her works.

More than anything else, the particularity that characterizes de Lempicka’s paintings lies in the combination of these modern elements with a plasticity of figures that recalls both classical sculpture but also the reworkings of the antique already proposed by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Imposing hieratic figures occupy almost the entire space of the canvas and are placed in front of neutral backdrops, in shades of gray, so as to stand out further. Just like ancient statues, draperies are often found in de Lempicka’s works, which are sometimes reproduced in a literal sense, while sometimes they are recalled by the flounces of dresses or the folds of scarves, modernizing them to the utmost.

Already the first work presented at the 1922 Salon, entitled The Two Friends, these characterizing elements begin to appear. The protagonists of the work are two young women who look almost like mannequins, as their gazes appear expressionless, detached, and the lines are very hard and sharp. The painting, however, did not meet with public approval both for its lack of expressiveness, and for the provocative allusion of a Sapphic bond between the two protagonists.

Dating from 1927 is Kizette at the Balcony, in which de Lempicka portrays her daughter sitting on a stool on the balcony. The pose in which she is portrayed is reminiscent of Agnolo Bronzino’s Portrait of Bia de’ Medici, an artist she loved and one that confirms her in-depth study of great Italian masterpieces. The most modern details concern the landscape overlooked by the balcony, which is deconstructed in a Cubist manner.

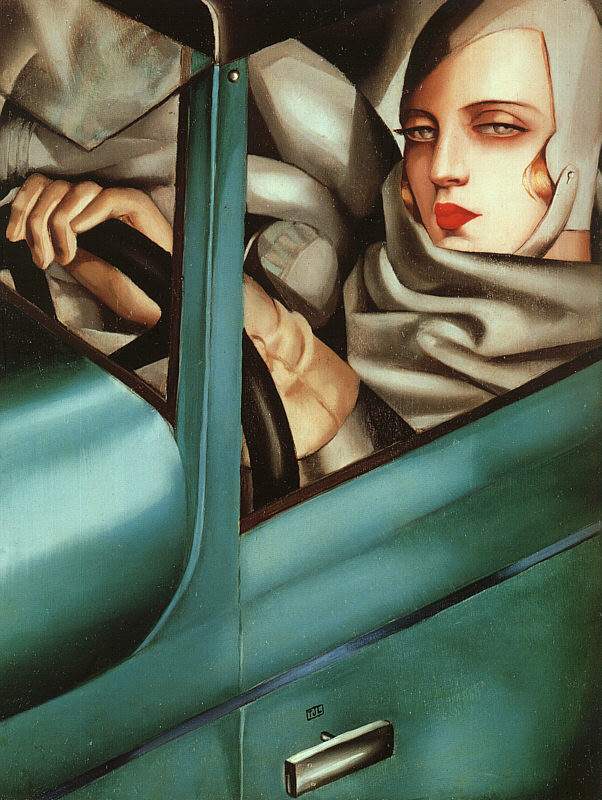

Great success was had, however, by the work Self-Portrait (1929), to the point of becoming a true icon of the time. The work was used on several occasions, for example as the cover of the German magazine “Die Dame,” and even today it is a symbol of women’s independence and emancipation, as well as the myth of speed typical of those years. De Lempicka portrays herself in a Bugatti convertible car, dressed in full regalia with gloves and scarves sheltering her neck and head from the wind. The woman’s gaze is proud, accentuating the sense of pride aboard her flamboyant car, and creates an effective contrast with the softness of the facial features and the geometric lines given by the movement of the scarf with the wind. The painting’s protagonist has often been likened to another fictional character in Francis Scott Fitgerald’s novel The Great Gatsby, namely the young socialite Daisy, love interest of the mysterious Gatsby. In this work, as in many others, it often comes naturally to recognize several influences from currents contemporary with her, such as Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s Futurism or Pablo Picasso ’s Cubism in certain angular ways of rendering lines and dividing forms into a kind of well-defined sectors. After all, his master was the post-Cubist constructivist and synthetic painter André Lhote.

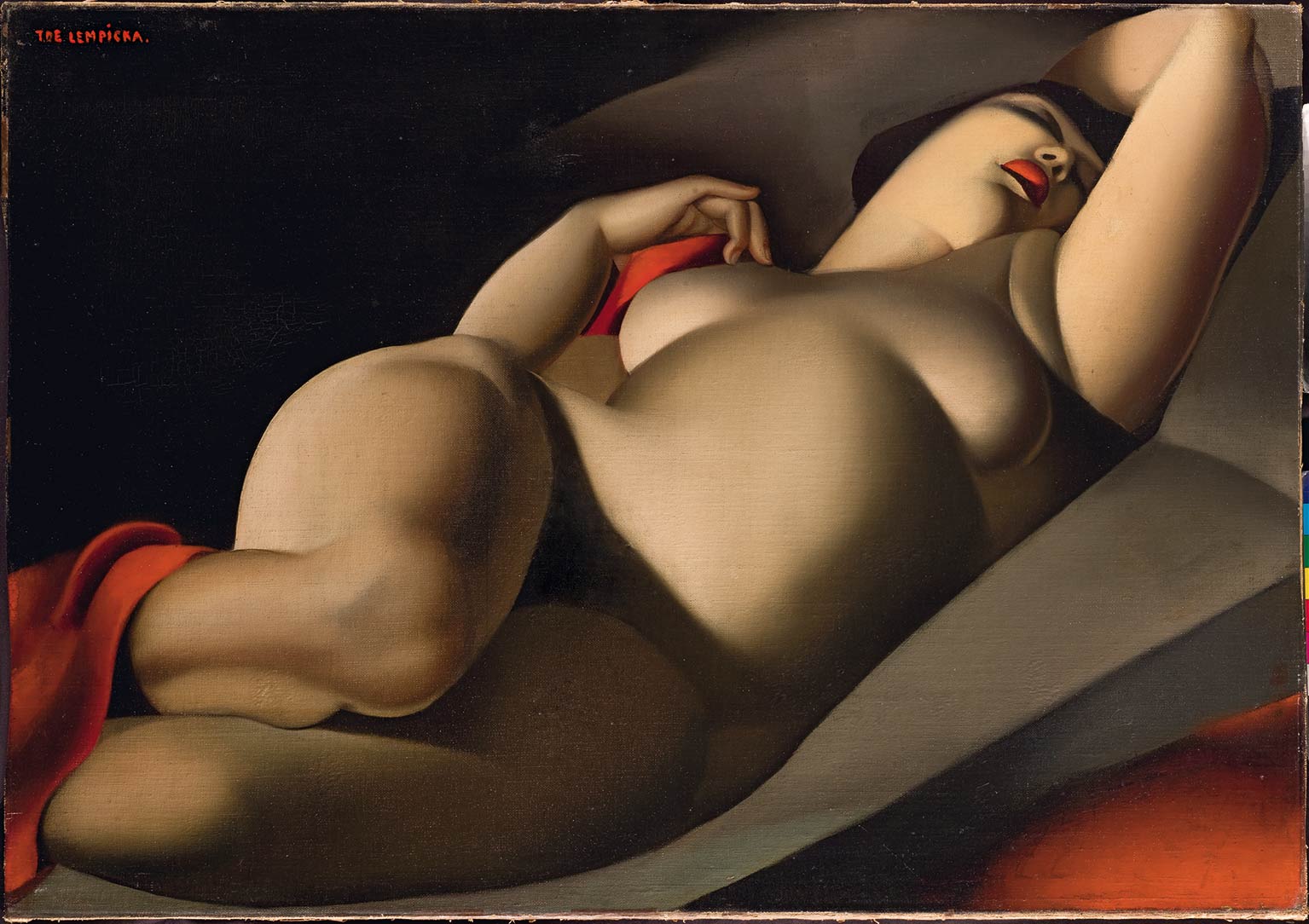

With regard to the theme of eroticism, especially in the Sapphic vein, De Lempicka elaborated a series of paintings featuring a young woman named Rafaëla, which turned out to be a direct reference to a passion experienced firsthand by the artist towards a woman who had deeply impressed her with her eyes and generous physique. A number of paintings dedicated to her were The Dream (1927), in which he gives the woman a feeling of tenderness and even shyness, evident in the gesture of covering her breasts that differs markedly from the winking glances of the earlier works, and The Beautiful Rafaëla (1927) in which the woman’s sensuality stands out throughout the painting. Similar in setting, and of great refinement and elegance is also Young Maiden with Gloves (1930), another very famous painting by de Lempicka that is striking in its rendering of draperies, which expand in space in numerous movements and folds almost as if the protagonist were a modern Nike of Samothrace.

The artist, after moving to the United States in the 1930s, decisively changed the themes of her works, opting for religious paintings that reflected a personal existential crisis that led her to remain inactive for several years. Painting religious subjects seemed to give her comfort, and De Lempicka confirmed even at this stage her tendency to bring to the canvas the people who were part of her everyday life. For example, she portrayed the mother superior of a convent in Parma in the painting The Mother Superior (1935), one of her most beloved paintings that she donated to the Museum of Fine Arts in Nantes, refusing to sell it. In another painting, however, she portrayed her psychiatrist in the guise of St. Anthony. Works between the 1930s and 1940s were divided between more Surrealist themes such as Key and Hand (1941), Surrealist Hand (1947) and humanitarian themes such as The Refugees (1931).

For a long period De Lempicka remained inactive, and it was not until 1957 that she produced new works, mostly abstract compositions, and later paintings made with a palette knife, which, however, did not meet with critical acclaim. They were the last works produced by the artist.

Tamara de Lempicka’s works can be found in some major European museums, while several of her works are in private collections, so it is possible to see them at exhibitions dedicated to the artist. The first painting, The Two Friends (1922), is in Geneva, Switzerland, at the Musée du Petit Palais.

In Paris, in the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou is Kizette at the Balcony (1927). In addition, the famous work Young Girl with Gloves (1930) was purchased by the French state for display in the Polish section of the Jeu de Paume National Gallery of Contemporary Art in the Tuileries Garden. Also in France, The Mother Superior (1935) can be seen in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Nantes. Finally, the works Self-Portrait (1929), La bela Rafaëla (1927), and The Dream (1927) are part of private collections.

In Italy there are no works by Tamara de Lempicka in public collections, so they can be admired exclusively at exhibitions dedicated to her, such as a major exhibition that was held in 2015 at the Palazzo Chiablese (in Piazza Castello) in Turin.

|

| Tamara de Lempicka, female icon of 1920s Paris. Life, works, style |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.