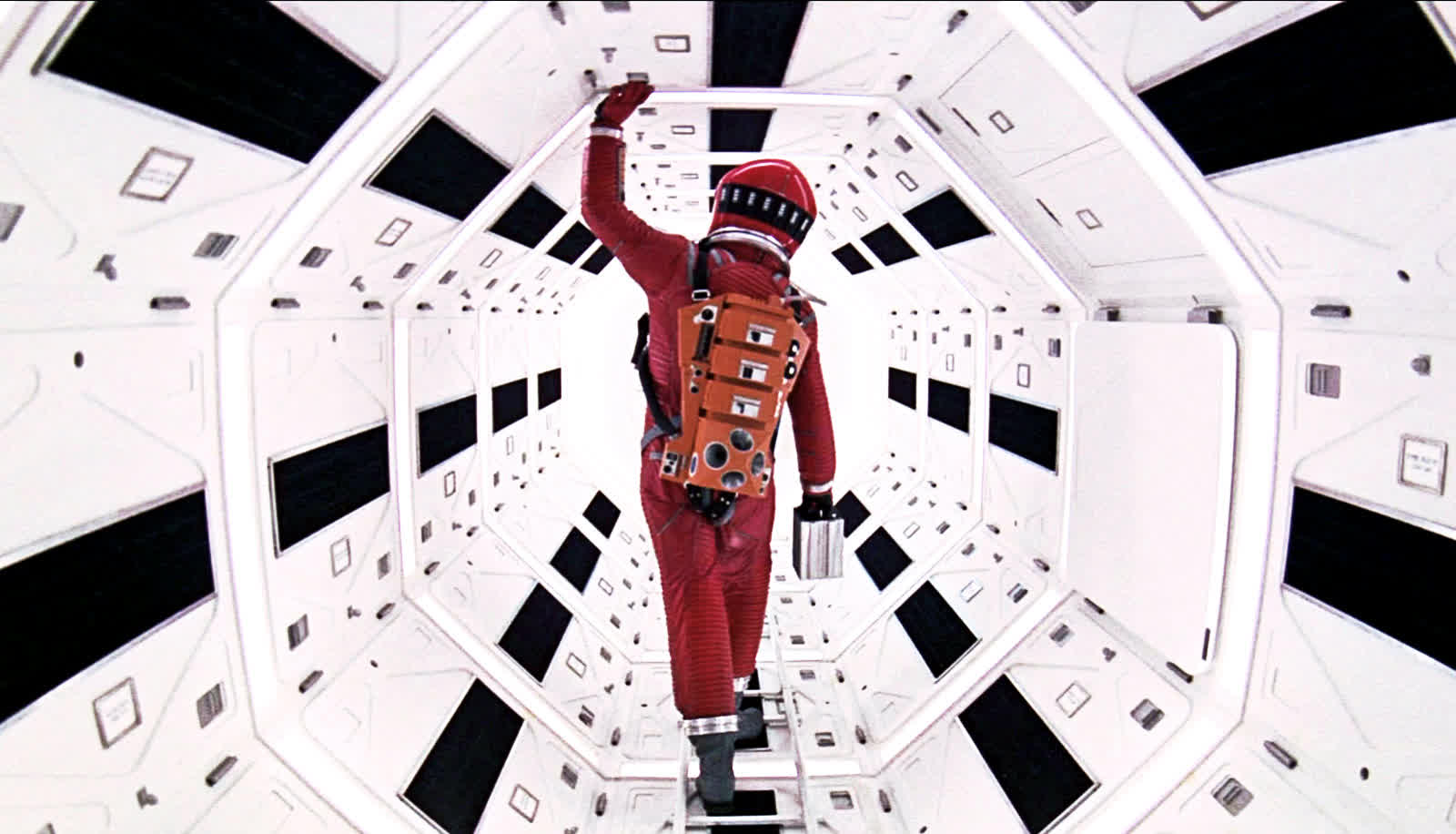

In December 1968, Italian cinemas screened the film 2001: A Space Odyssey for the first time. A film in four chapters that chronicles an evolutionary leap in human consciousness and technological capability, set against the backdrop of an alien intelligence directing change. Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece explores the present, a past and a future, from the dawn of man, set in a prehistoric Africa, to a future in 2001, when humanity would colonize the Moon, reach Jupiter, and beyond. Alongside Stanley Kubrick, the other mind behind 2001: A Space Odyssey was Arthur C. Clarke, British science fiction writer, science essayist, inventor, and television host. The two collaborated on the film’s screenplay, the result of a deep understanding that combined Clarke’s scientific vision with Kubrick’s cinematic abstraction. It was Clarke himself who would introduce our theme for today, “Thinking the Museum of the Future.”

Back in 1964, in a BBC broadcast, Arthur C. Clarke presented his vision of the future, making a series of incredibly accurate predictions about technology and society. “Trying to predict the future,” Clarke had reiterated, “is a daunting and risky endeavor because the choices the prophet would have before him are not easy. If his predictions sounded even vaguely reasonable, you can be sure that in twenty or at most fifty years advances in science and technology would make him seem too conservative. On the other hand, if by some miracle that prophet described the future exactly as it will happen, his predictions would sound so absurd, so improbable, as to create perplexity and disbelief.” I am not a prophet, nor do I intend to be one, but I follow Clarke’s steps recognizing the risk of sounding absurd, perhaps even too far from reality, but hoping not to leave you puzzled or incredulous. It is precisely for this reason that I choose to analyze the museum through the lens of the futures cone, “cone of futures” in Italian.

The Futures Cone is a conceptual method of exploring a choice of futures from the present, to understand the possibilities within an increasing uncertainty as time passes. I choose to focus on four different types of futures.

The first concerns possible futures. These are anything that could happen, based on imagination, the limits of science or unknown variables. For example, extreme weather conditions might be possible, considering rising temperatures. The second concerns probable futures. These are futures that have a high probability of happening if current trends continue. Travel to Mars is increasingly likely. Increasing reliance on artificial intelligence would be another likely scenario. The third is about preferable or desirable futures. Here we talk about futures to which we aspire. We all believe in an inclusive society; there are many of us who are committed to promoting inclusiveness, diversity and equity. The fourth is about plausible futures . Based on current trends, expert knowledge and research, some futures could happen. These are the futures that are likely to happen if current trajectories continue.

The choice between possible, plausible, probable, and preferable depends largely on a deep understanding of trends and the ability to read the signs of the times.

With the choice of futures that the cone of futures provides us with, we could map the futures of a particular museum institution, certainly not definable from general characteristics. It would be about a particular typology, a specific way of understanding and experiencing the museum-the Mediterranean museum. It would be about an institution historically designed to protect, preserve and make accessible an extraordinary historical and cultural heritage, an institution deeply rooted in the cultural landscape in which it is located, to be understood as a container of content that often has the same value and meaning as the cultural heritage it contains. It would be about an institution that enhances, presents and makes accessible a cultural heritage often understood and valued as a direct extraction from the past-a relic-that directly recalls cultures shaped by religious practices, considering that the Mediterranean is also the cradle of the three monotheistic religions.

This is the museum whose futures we are considering today, and we will do so by dwelling on three elements.

Many of us come from collecting institutions, which often hold significant collections. We know that Italy has some of the most important concentrations of collections in the world, with a very high percentage often in deposit. ICOM Italy’s recommendations on museum deposits, published following the Matera conference at Palazzo Lanfranchi in 2019, had focused precisely on a need to enhance the value of deposits. After that, as we well know, these recommendations were taken up by the ICOM General Assembly with a commitment to promote greater attention to the preservation and enhancement of collections in storage around the world.

We should add that collecting institutions continue to struggle with management practices that date back to 19th century museum concepts, in which storage and study collections are distinct from the exhibition often referred to as “permanent.” In this sense, museums often behave like that child St. Augustine meets by pure chance, that child trying to pour the ocean into a hole in the sand, continuing to acquire and collect (rightly, I might add), but then failing to present it and make it accessible, leaving many St. Augustines wondering why.

What futures, then, for this museum materiality so central to the Mediterranean museum? What possibilities for future management? In November 2021, the Boijmans van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam opened its Art Depot, a spaceship-like architecture designed as a publicly accessible storage facility. It would be the first of its kind but, they reiterate, it is not a museum, as is made clear at the entrance to the Art Depot. Instead, I seriously believe that this project, starting with an emerging trend, could become a new museum concept. It could be possible, perhaps even preferable in view of collection development, and compatible with the current definition of a museum.

The ICOM 2022 definition recognizes the museum as “a permanent nonprofit institution serving society that researches, collects, preserves, interprets and exhibits cultural heritage, tangible and intangible. An open to the public, accessible and inclusive institution that promotes diversity and sustainability, operating with community participation by offering diverse experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing.” At the Rotterdam Art Depot, visitors are invited to discover how art is acquired, studied and restored. All of these are values found in the ICOM definition, but beyond that, the Art Depot has an educational program, curated exhibitions, educational spaces, and even a restaurant with a panoramic view of the city. There is not much in all this that goes against a new idea of a museum being experimented with, because nothing goes against the ICOM-promoted definition of a museum starting in 2022.

This trend is projected in the design of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s new storage facilities, the East Storehouse, which opened a few weeks ago. The East Storehouse will promote on-demand access to objects in storage as a component of a true self-storage experience. QuoteTim Reeve, V&A East Storehouse director of operations, in English: “We’ve got two museum modes: one is permanent galleries and exhibitions, the other is storage. We’ve tried to invent a third one in the middle. I hope it will move away from that binary choice between display or storage.”

Since 2010, Nina Simon has emerged as a point of reference for the idea of a participatory museum, although this approach has as its historical background sociomuseology, nueva museología or nouvelle museologie traced back to the 1973 Santiago Declaration of Chile. ICOM’s 2022 definition of a museum refers to the increasingly central role that the community takes on in museums, not only as an audience, but as an active participant, and in many cases co-creator.

What futures for museum audiences in the 21st century? How can we reconcile curatorial ’authority with community participation in the museum guided by a commitment to inclusivity? In 2018, the Anchorage Museum, Alaska, thanks in part to financial support from Bloomberg Philanthropies opened Seed Lab, transforming an abandoned building right across the street from the museum into a place for the community.

Seed Lab contains lecture rooms and theater space in addition to the tools library-a lendable tool library-as much as a library does with book lending. But what really matters is that Seed Lab is designed to become the place to incubate the museum’s programming for and with the community. This project, too, can be seen as a seed of possible, perhaps preferable futures when we think about the fundamental role that relevance has and continues to play in a museum’s operations. It would certainly be a plausible future, observing the evolution of co-creation and inclusion practices increasingly employed by museums around the world.

Beware, however: whether a future is preferable or not depends almost exclusively on museum leadership. Museum leadership must know how, when, and in what ways to involve the community in both the day-to-day museum process and in co-creating a program of activities for and with communities. It would be similar to how a conductor engages in conducting a polyphony, not a cacophony, making sure that all the instruments are playing at the right time and in the right way. It would be the same thing that a museum director must do in the future-possible, plausible, and perhaps even preferable.

The museum of the future is often thought of as a predominantly technological museum. This would be an image rightly fueled by the profound and, I might add, unprecedented technological changes we are experiencing. Some have compared this moment to the industrial revolution of the 19th century.

Let us return to what Arthur C. Clarke said in 1964, imagining a future set in the year 2000: “When that time comes, the whole world will have shrunk to a point, and the traditional role of the city as a meeting place will no longer make sense. In fact, humans will no longer travel - they will communicate. These technologies will make possible a world in which we can be in immediate contact with anyone, wherever we are. We will be able to communicate with friends anywhere on Earth, even if we do not know where they are physically located. It will be possible in that era-perhaps only fifty years from now-for a man to work from Tahiti or Bali as effectively as he would work from London.”

It is a fact that museums, like contemporary societies in general, struggle to keep up with innovation. Here again the image of the child meeting St. Augustine on the beach comes back. Technology is advancing, and the museum is trying to contain it in a space designed for other times, despite the fact that it may offer the museum an opportunity to be a much more incisive part of an extraordinarily interconnected world.

What futures, then, are possible through technology? What preferable scenarios if we think from the perspective of figitale combining and juxtaposing physical and digital experiences? Should museums consider technology as an extension of the museum experience, accessible on multiple platforms? We all experienced the Getty Challenge during the pandemic, recognized by all of us as a historic moment when the museum expanded beyond its physical limits and on a global scale as never before. Could museums explore a parallel physical and digital dimension driven by transmedia? In October 2022, the Finnish National Gallery, together with Decentraland and Sitra, opened one of the first national museum spaces in the metaverse with a digital version of the Finnish pavilion at the 1900 Paris Expo as a museographic project, where visitors can vote and influence the choice of exhibits.

Perhaps museums should focus instead on using technology as a tool to interpret the traditional museum experience, consolidating meaning and value of a materiality still central to the Mediterranean museum? I am not referring to static and silent virtual tours, barely alive replicas of empty museums. I am talking about interactive experiences like that of Gallery One at the Cleveland Museum of Art, where the emotional reaction of the museum audience determines the choice of works.

By now, Fiona Cameron’s liquid museum concept dates back more than a decade. Moreover, everything the museum needs in terms of technology has already been invented. The real challenge is to find purpose of application and utility to this technology. I am perfectly convinced when I say that a museum idea of a possible, even plausible future would be that of a multisensory museum, accessible from anywhere on the planet. It will be possible for a person to access a complete museum experience wherever he or she is-from Tahiti as much as from London or from here, from Bologna. Those who have caught the analogy know that these words recall Clarke’s 1964 prediction. Sixty years ago. Perhaps I would be predictable, even absurd, I might add. I leave the choice and decision to you. As Clarke said, “The only thing certain about the future is that it will be absolutely fantastic.” But what will really drive museum innovation will be human capital. I am thinking of European projects such as the CHARTER Alliance that has identified 115 heritage professions, some specific to the museum institution, to which are added hybrid roles and new job profiles for a combined total of more than 150. In fact, job profiles continue to evolve. I mention just a few emerging roles such as online cultural community manager, digital strategy manager, digital collections manager and digital material curator, identified by the project Mu.SA - MuseumSector Alliance, in which the Institute for Artistic, Cultural and Natural Heritage of Emilia Romagna also participated.

Some of these roles will have to be rethought, others reinvented. Artificial intelligence will also weigh in, bringing with it challenges and possibilities. But to get there, we need to better understand the possible, the plausible, the probable, and the preferable. We need to ask how the idea, the concept of the Mediterranean museum can evolve, be reborn if need be, how it can, must and will transform itself to remain more and more an institution of relevance to community and society.

The author of this article: Sandro Debono

Pensatore del museo e stratega culturale. Insegna museologia all'Università di Malta, è membro del comitato scientifico dell’Anchorage Museum (Alaska) oltre che membro della European Museum Academy. Curatore di svariate mostre internazionali, autore di svariati libri. Scrive spesso sui futuri del museo ed ha il suo blog: The Humanist Museum. Recentemente è stato riconosciuto dalla Presidenza della Repubblica Italiana cavaliere dell’Ordine della Stella d’Italia e dal Ministero della Cultura Francese Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres per il suo contributo nel campo della cultura.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.