Important archaeological find in Spain at the Casas del Turuñuelo site in Guareña, a town in Extremadura, the country’s western region near the border with Portugal. An excavation has in fact unearthed, among the many materials recovered, a small slate slab about 20 centimeters across engraved on both sides. There are what appear to be drawing exercises conducted through the continuous repetition of faces or geometric figures, and a combat scene in which three characters, probably three warriors, interact. Early indications, according to the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), the counterpart of our CNR, suggest that this piece, unique in the archaeology of the Iberian Peninsula, probably served as a support for the craftsman to engrave motifs on pieces of gold, ivory or wood. The find is supposed to date from the time of the Tartessus culture (13th-6th centuries B.C.).

The team from the Institute of Archaeology of Mérida (IAM), a center jointly run by CSIC and the Government of Extremadura, headed by Esther Rodríguez González and Sebastián Celestino Pérez, is responsible for these archaeological excavations, which have previously made headlines for the discovery of the largest animal sacrifice in the Western Mediterranean. “This discovery,” says Esther Rodríguez, “represents a unique example in peninsular archaeology and brings us closer to the knowledge of the craft processes of Tartessus, hitherto invisible, and at the same time allows us to complete our knowledge about the clothing, weapons or headdresses of the characters . represented, since details abound in them.” This documentation complements the discovery made in the last campaign, where the documentation of multiple faces made it possible, for the first time, to admire how 6th-5th century B.C. society wore its jewelry.

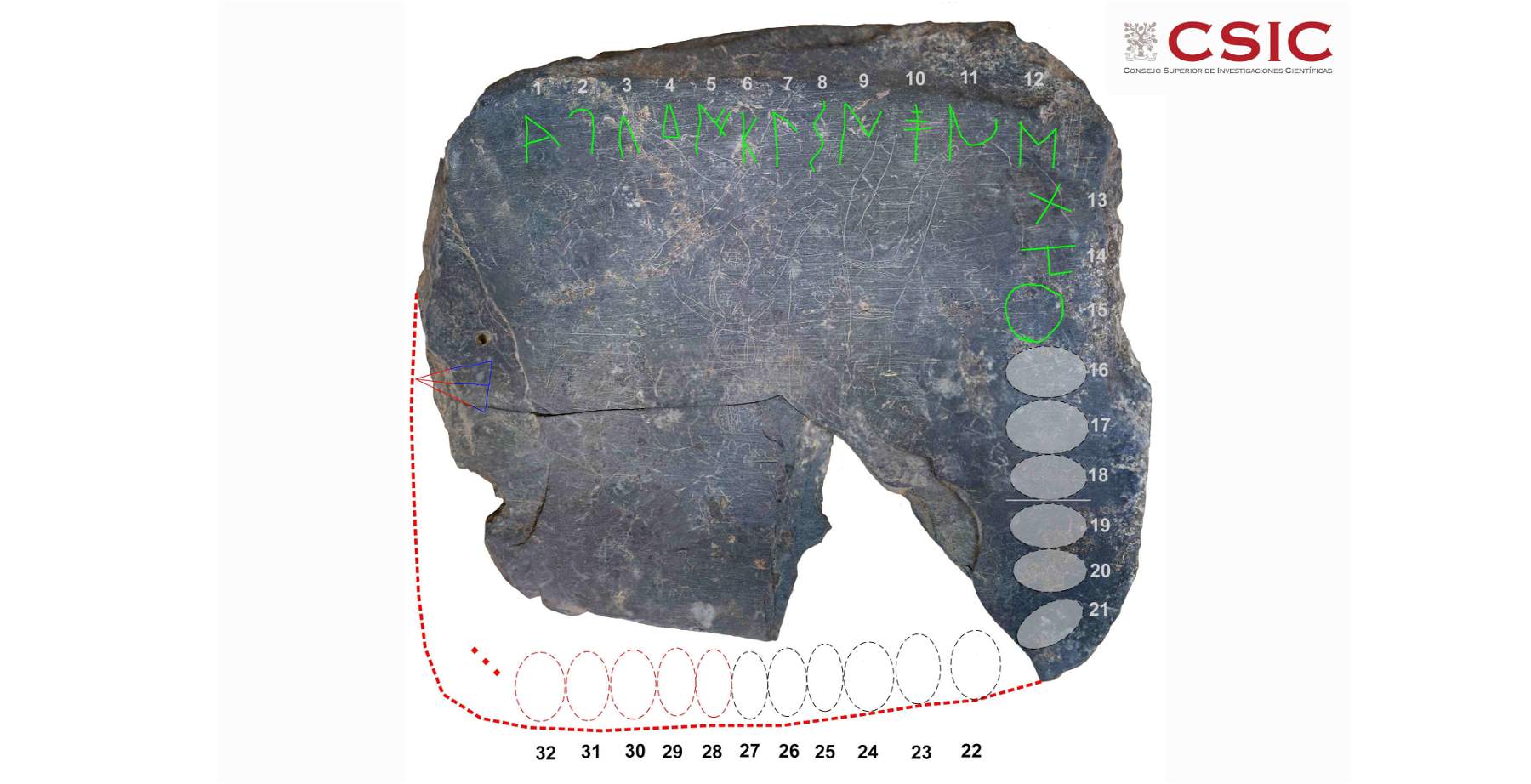

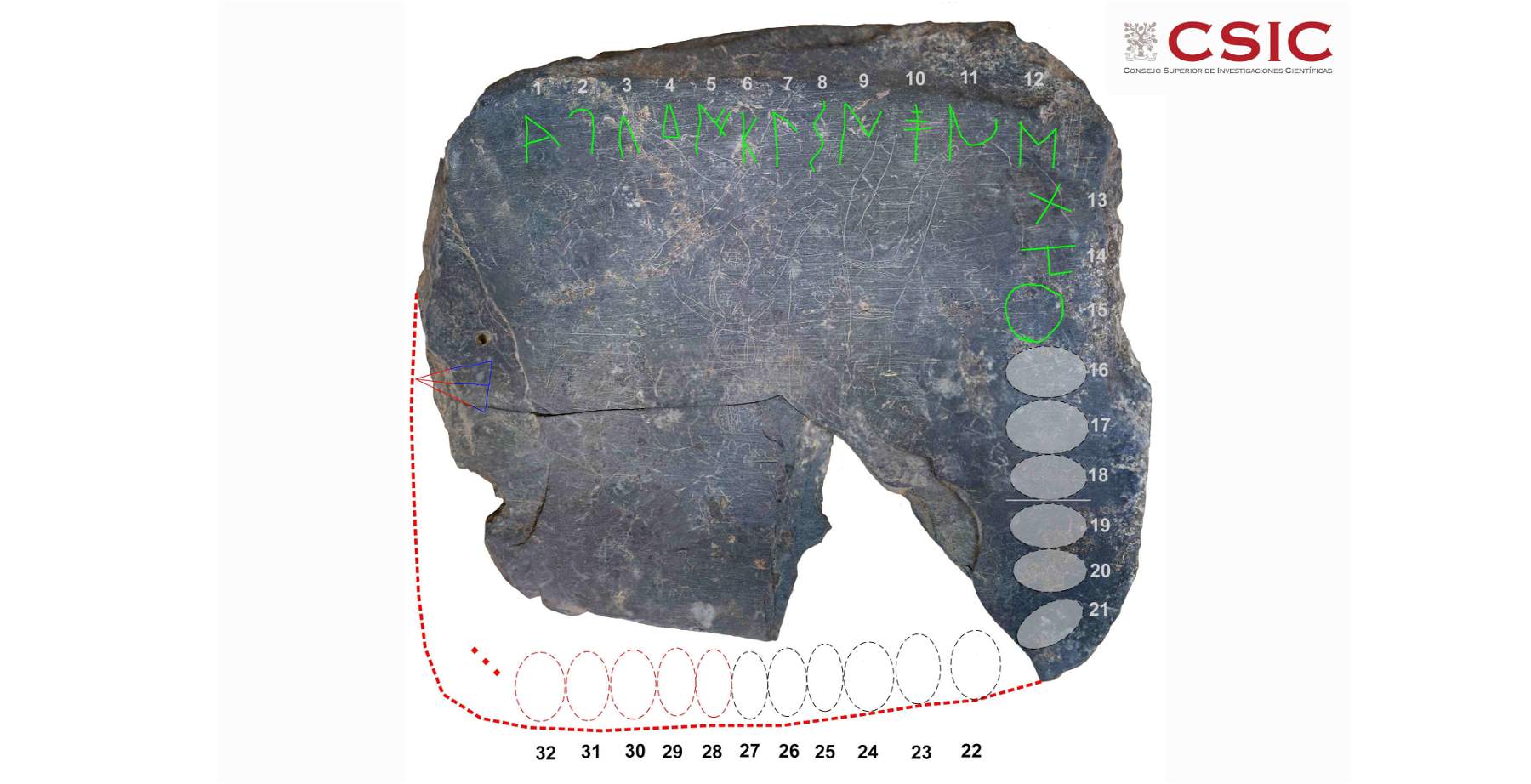

But the surprises did not end there. In fact, researchers at the Institute of Archaeology in Mérida began a few days ago to study a series of signs engraved on the slate tablet that, according to initial interpretations, would compose an alphabet from a southern Paleo-Hispanic script. Researchers in charge of work at the site, are collaborating with a researcher who is an expert in this type of writing after identifying what appears to be a sequence of 21 signs drawn on the edge of the tablet in which figures of warriors were also found. Experts point out that this would be the third known alphabet of a southern Paleo-Hispanic script.

Research on this new alphabet began thanks to the report of a scholar, Joan Ferrer i Jané, a researcher in the LITTERA group at the University of Barcelona, who learned from the media about the discovery of the slate tablet with the silhouettes of three warriors at the Extremadura site. “Beyond the figures, when I looked at the plaque I saw that on one of the sides there seemed to be a Paleo-Hispanic sign, a sign that cannot be confused with any other. Other traces compatible with signs of a known sequence were also observed,” he explains. Ferrer therefore contacted the team at the Institute of Archaeology in Mérida and requested partial macrophotographs of the area to corroborate his suspicions. “After studying the images, everything indicates that it is a southern alphabet with the initial sequence ABeKaTuIKeLBaNS?ŚTaUE, which is almost the same as documented in the Spanish alphabet, except for the eleventh sign, which has a special form,” Ferrer i Jané indicates.

Today, modern alphabets retain the initial sequence ABCD, which is derived from Phoenician. The one found at Guareña begins with the sequence “ABeKaTu,” which would be its equivalent, and would have 21 signs written in the left-to-right direction following the outer edge of the plate. “At least 6 marks would be lost in the divided area of the piece, but if it were completely symmetrical and the marks completely occupied three of the four sides of the plate, it could add up to 32 marks, so the lost marks could add up to eleven or maybe more if a possible sign, ’You,’ isolated in the fourth side, was part of the alphabet,” comments Ferrer i Jané, who adds that “it is unfortunate that the final part of the alphabet was lost since that is where the most pronounced differences tend to be.”

Paleo-Hispanic writings are divided into two families: the northeastern family and the southern family. The boundary between one and the other would be, approximately, south of Valencia. They all derive from the Phoenician script, from which an initial adaptation was made to what is called the original Paleo-Hispanic sign and then two different adaptations were produced, one to the north and the other to the south. The latter is the one that gave rise to the southern script family, to which this alphabet would correspond.

So far there is only evidence for the existence of two other southern script alphabets. According to initial investigations, the Guareña alphabet repeats at least the first 10 signs of the alphabet of the Espanca site, attested at Castro Verde (Portugal). “This alphabet has 27 signs and is the only complete one we knew until now. Another one was found in the excavation of Villasviejas del Tamuja (Cáceres) but it is very fragmented, having only a few central signs. So Guareña would be the third and would provide a lot of information,” Ferrer says.

Esther Rodríguez González pointed out that from the first moment the slate tablet was found she was aware that “the volume of information it contained was even greater than that the faces found.” In addition to the silhouettes of human figures, scientists had already observed several circles and lines that suggested that the slab could be analyzed at different levels. Currently, Esther Rodríguez and the rest of the IAM researchers, along with Joan Ferrer, are studying the extent of the signs identified and the importance they might have as examples of Southern Paleo-Hispanic writing.

Collaboration among the researchers will help determine whether the Casas del Turuñuelo alphabet can be classified within any of the already known scripts or whether it should be considered an independent southern script. “In any case, this confirms that there are many other inscriptions hidden at this site that we hope will come to light in future campaigns,” Ferrer i Jané concludes.

|

| Spain, archaeologists discover slate slab with an ancient alphabet |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.