There is perhaps some significance in the fact that one of the biggest revolutions in painting of the 19th century started in Livorno. Vincenzo Farinella, lone curator of the Giovanni Fattori 200th anniversary exhibition that recently opened at Villa Mimbelli, did not hesitate to use precisely the term “revolution” to subtitle the most comprehensive review on Fattori seen at least since the one Andrea Baboni curated in 2008 for another anniversary, the 100th anniversary of his death. Malaparte said that Leghorners are like water: they “want to move, walk, run, turn the world.” And if they stand still, they stagnate. Now, Fattori certainly cannot be said to have traveled the world: his cosmos was between Leghorn and Florence. Plus a few rare descents to Rome and a single trip to Paris, by the time he was in his fifties (he had set out rather biased, and would return less than satisfied). That hundred miles between sea and hills was more than enough for him, however, to change the face of Italian painting. Farinella, in the opening of the catalog, offers an icastic, fulminating summary of that revolution, first claimed by Fattori himself, and then already recognized by some of his contemporaries, and then still overlooked, underestimated, if not completely ignored, by a large part of our twentieth-century criticism: breaking with academic rules, notably of perspective space and proportional relationships between figures, and experimenting with new methods of spatial construction.

It is no exaggeration to say that Fattori had come to overturn six centuries of Italian painting. Without, however, denying its rules: his revolution should not be thought of as the action of a foreign body, of an outsider who had set himself the goal of overthrowing the system from the outside. Fattori did not have the temperament of the futurist: he was indeed swaggering, polemical, stormy, rigid, not at all inclined to compromise and perpetually dissatisfied, but he was not an incendiary either. If anything, Fattori is the rebel who acts from within, the protester who shakes the foundations of the system and ends up leading its revolution from within. He was somewhat aware of this, even though he was convinced that he was part of a movement, of that “revolution of art, the ’stain,’” to use his own words, which he traced back a few years before his personal breakthrough. However, his revolution was not limited to the “macchia”: Fattori, for the reasons mentioned above, was even more radical than Signorini, than Banti, than Cabianca, than all the artists who had experimented with the “macchia” before him. And it is then a revolution that perhaps still needs wider recognition. That we tend to consider Fattori one of the pillars not only of our nineteenth century is something that is now perhaps taken for granted. Raffaele Monti considered him a father of Italian culture on a par with a Giuseppe Verdi, to whom, moreover, he had already been compared by Manganelli in Il Messaggero at a time when Longhi’s night on Fattori was already moving toward the dawn’s glow (“Like Verdi, Fattori is a great tempter: the warm humanity, the slice of reality, the testimony of life.”). The main merit of Farinella’s exhibition, without wishing to take into account the indisputable completeness of its reconstruction, is, however, that of having laid the groundwork to make sure that we finally realize, beyond the favor the Leghorn artist unquestionably enjoys if one must speak of taste (it is a fact that exhibitions on him are counted almost annually: he is one of the artists most beloved by the Italian public, and consequently he is among the most beloved by our exhibition organizers, but one also has to wonder how many of the latest exhibitions on Fattori have really added anything), that Fattori is a painter of European caliber.

The curious aspect of the whole thing is that the beginnings of this revolution still seem rather misty, cloaked in a light blanket of fog. It must also be said that, if it were not for a letter, perhaps we would not have Giovanni Fattori’s works today, and perhaps the history of Italian art would have taken other directions, probably less interesting than those that Fattori managed to establish, to impose, to follow along a career that lasted fifty years. The letter is one that his father sent him in March 1849, in an attempt to dissuade him from participating in the defense of Florence in the weeks of the Austrian invasion against the insurgents who had proclaimed the republic and forced Grand Duke Leopold II to leave Tuscany. We do not know Fattori’s response, but since we know him shortly thereafter in Livorno we must imagine that he had to heed his father’s advice. For then, it was what any parent would tell their child: don’t put your life on the line, think of the sacrifices made by father and mother, imagine the family’s pain. At the time, Fattori was a 24-year-old who had not yet done anything good, much less interesting. Had he left for the front and never returned from the front, today we would count him among the many shoddy artists who populated mid-nineteenth-century Tuscany, for such Fattori remained until nearly the age of forty: a mediocre painter, an artist of little talent, an immature and arrogant student, good only for messing around, wasting his time in the dive bars of Florence, at most taking an interest in politics, the only passion capable of igniting him when he attended classes at the Accademia. A “clamorous, overbearing and ill-mannered” student: that was how the final judgment of a course he had passed with the minimum of difficulty branded him. How he managed, within a very short time, to shed the guise of the listless and boisterous student and become “the most significant painter and engraver of the second half of the Italian nineteenth century,” according to Farinella’s well-shared definition, is perhaps not yet well understood. For the prodromes suggested otherwise, and the revolution came immediately.

In the space of a review it is difficult to give an account of such a vast and dense itinerary as the one imagined by Farinella: the more than two hundred works arranged along twenty-four sections that occupy the three floors of Villa Mimbelli (the museum was temporarily emptied of the permanent collection to make room for the exhibition: given the importance of the occasion, the choice can be forgiven for this time, as long as the rearrangement is then lightning-fast) end up keeping anyone willing to devote any attention to the exhibition at least a good three hours, which pass, however, as if they were a quarter of an hour, because there is no sagging, no repetition, no filler, and the tour itinerary is structured the old-fashioned way, with a tight chronological order that at best indulges in a few thematic lunges to offer the audience some soft dissonance to a score that proceeds quietly, calmly, smoothly. Given the size, it will be necessary, therefore, to proceed in sum and focus on the key junctures, and one of these junctures comes immediately in the opening. It is hard to believe that the Fattori in the second room is the same painter as in the first section, where Farinella has gathered almost all the known and surviving early works (there are some drawings that look like those of a teenager, an ex voto certainly burdened by the schematics of the genre but nevertheless terrible, a history painting, namely The Death of King Manfred, so bad that it is attributed to him with a question mark, and a more successful Reading Lesson in the Garden for which one suspects, however, touch-ups perfected when by then Fattori had become Fattori). The comparison with his masters and early references (his first mentor, the Leghorn-born Giuseppe Baldini, and then two history painters, Giuseppe Bezzuoli and Enrico Pollastrini) borders on cruelty, railing against those early, stunted proofs that have nothing of’interesting and that reveal to us a painter who at the threshold of thirty was still struggling in the rut of a history painting destined to leave the orbits of the most up-to-date art, one of the many epigones of the last Romantic painters who painted in the Florence of the Lorraine.

Then, at a certain point, when Fattori was still a history painter, the sudden turning point. It was 1859 and he was painting a large canvas, two by three meters, with an episode of Florentine history(Clarice Strozzi intimates to Ippolito and Alessandro de’ Medici to leave Florence), moreover recently discovered, because when the work was almost finished Fattori decided to spread a coat of paint over it to cover that image and paint on the back a work of quite a different scope, his first major battle, theEpisode of the Battle of Montebello, which dates to 1862. Immediately following the abandonment of the large history-themed painting, however, is a series of tablets of soldiers that are surprising in their modernity: simple paintings, no longer of history but of reality, where the brushstrokes sketch luminous inlays of light and color spread in juxtaposed speckles, where the subject appears almost sublimated, where the grammar verges on geometric notation, and where already one can appreciate, Farinella writes, “an early hint of that willingness to undermine perspective space and the proportional relationships between figures that would emerge powerfully in the paintings and etchings of the last decades: if the group of soldiers, anchored to the ground only by the small shadows they carry, seems to float on a two-dimensional surface, the proportions of the figures in uniform do not respect, indeed overturn, academic laws.”

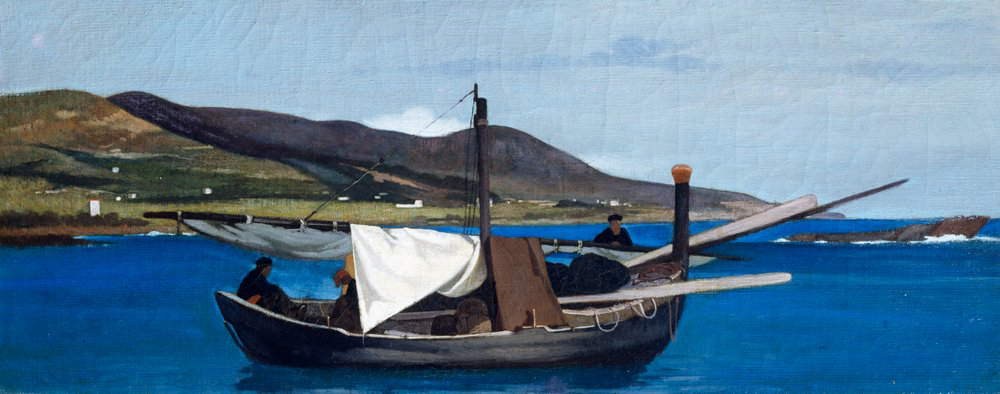

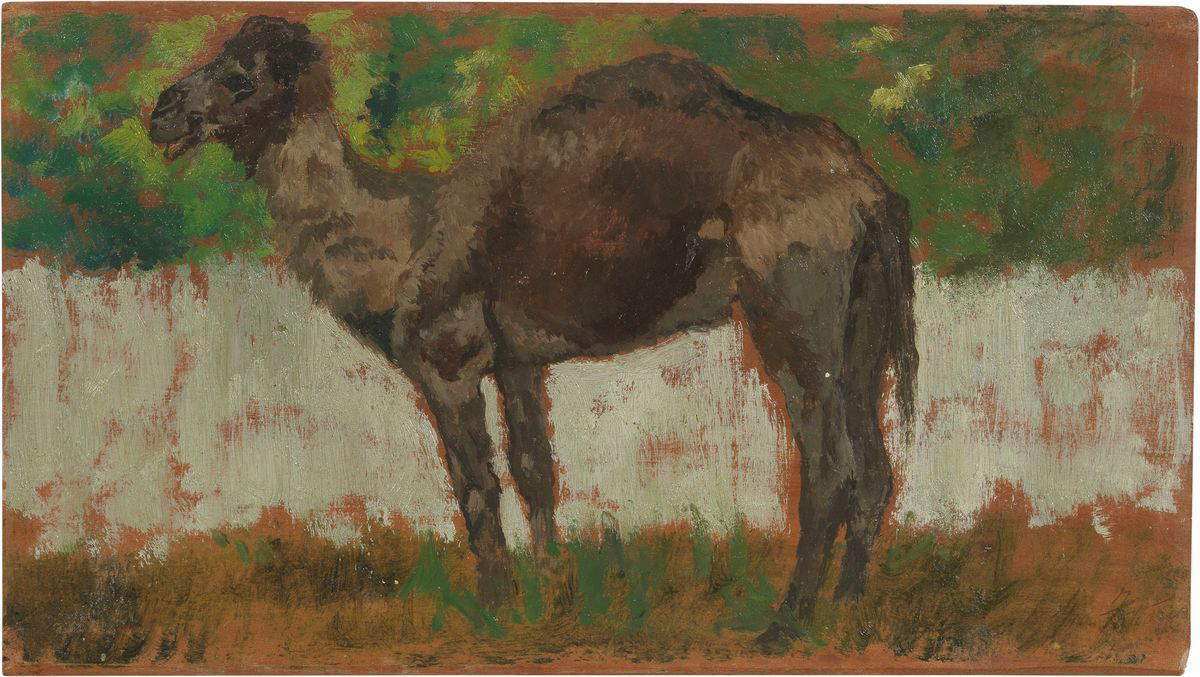

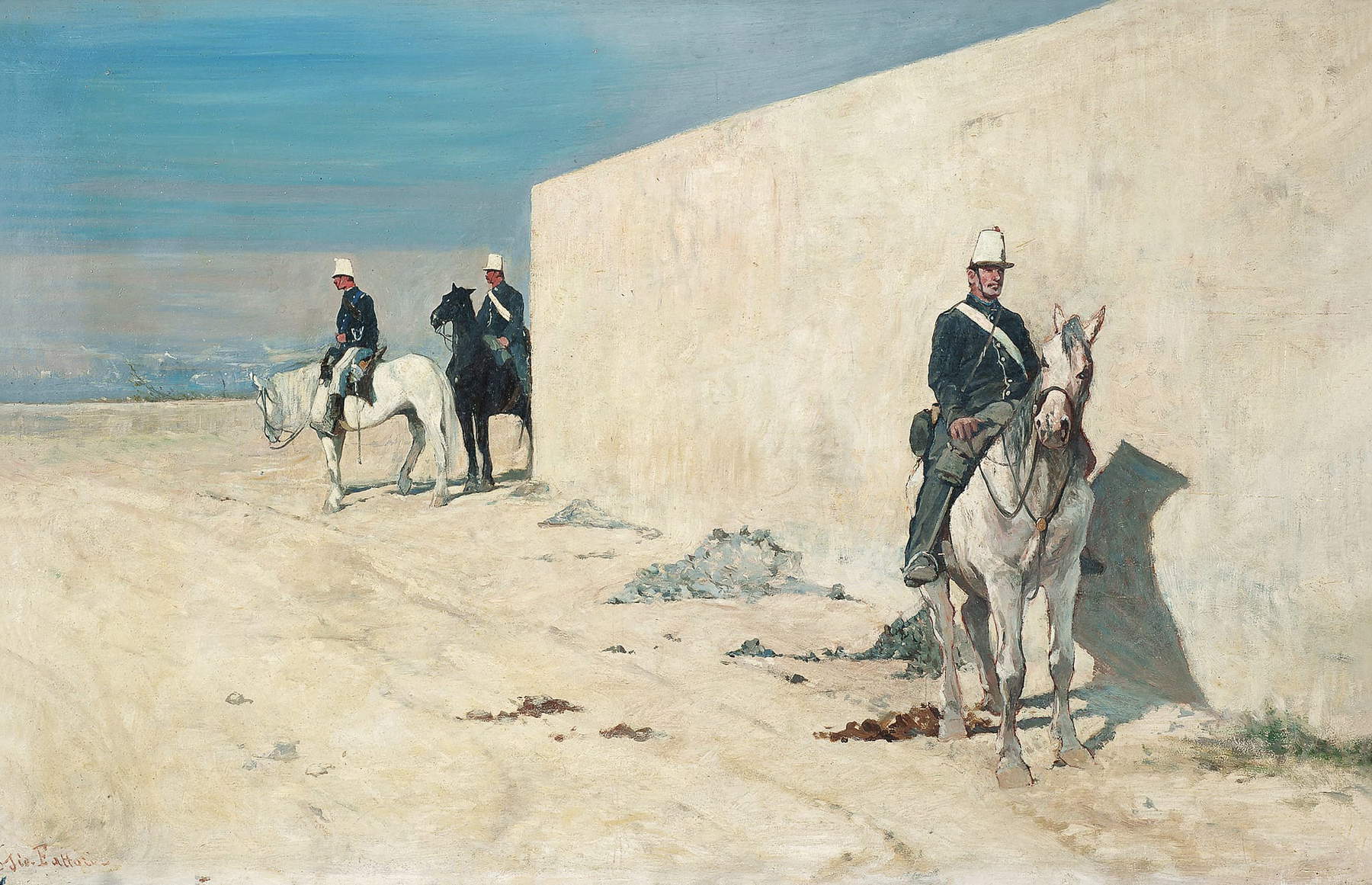

A blaze, a change so rapacious from those mediocre history paintings that one might think of it as a kind of epiphany, a mystical conversion. What had happened, and where Fattori had learned to paint like that, is hard to say. What is certain is that he himself, in his memoirs and in his few autobiographical writings, identified that 1859 as a fundamental year in his journey, the year in which “the Macchiaioli came,” as he himself would have written, although in reality his ’59 soldiers must probably have been the result of some more elaborate meditation. First of all on the works of Telemaco Signorini, Vincenzo Cabianca, Cristiano Banti, Serafino De Tivoli, of all those artists who had begun at least two or three years earlier their experiments on a new painting, a painting of visual synthesis that, to use Fattori’s own words, intended to restore to the relative “the reality of the true impression of the true.” This, then, was the premise of the revolution. To the observation of his colleagues’ experiments should then be added the meeting with Nino Costa (on display are some of his paintings), the inventor of modern Italian landscape painting, who was stunned by those early experiments on soldiers, and consequently intended to suggest to Fattori to try his hand at landscape as well. Fattori’s early views are another key junction in his art and date from the early 1960s, another period of fruitful activity favored by his proximity to the countryside of the Livorno hinterland. Every detail fascinates the now almost 40-year-old Fattori: the plowed fields, the cultivated ones, the sky above the expanses of grass and soil, the profile of the hills, the animals grazing or in the wild, and of course the life of the peasants, which, throughout his career, Fattori would reproduce without any idealization (attracting from the very beginning the polemics of a criticism that, accustomed to history painting, saw no reason to bring back to painting the humble existence of those peasants). Of course, Fattori’s repertoire could not lack the sea, an element to which the painter would always feel close: “I love the sea because I was born in a seaside town,” he would later say in his autobiographical writings. The experiments Fattori conducted between the early 1960s and the end of the decade also marked the moment of maximum formal synthesis: works such as the Acquaiole, the study for Pasture in Maremma, the Bagni Squarci, the Torre del Magnale, and the Punta del Romito (in its two versions, the one on canvas, which is more sparse, and the richer, saturated, summer version painted on panel) stand at the apex of this experimentalism, along with the masterpiece that is The Rotunda of the Palmieri Baths, preserved in the Pitti Palace and unfortunately not lent for the exhibition (it is, however, echoed by a Lady in the Sun from the same period and the same temperament), as well as several other works owned by the Uffizi Galleries that would also have figured well at Villa Mimbelli, given the solidity of the scientific project and the relevance of the exhibition.

The exhibition also seeks to dispel the myth of Fattori as a peasant painter, a crude painter, a poorly educated painter, a totally genuine painter. A myth that the painter himself, with his writings and memoirs, certainly helped to nurture, repeatedly claiming his modest origins, presenting himself as an artist who had received an elementary literary education (“a single and modest teacher taught me to write without giving me any other culture,” he would write in a 1901 memoir), flaunting his alleged lack of culture as a banner. This understatement that Fattori tried to enforce throughout his life had the precise purpose of corroborating that aura of the simple painter, the genuine artist, the continuous observer of nature who was inspired only by nature, an imitator of no one, free from any conditioning in his urgency to manifest his feelings. From his correspondence and, above all, from studying the visual references in his works, however, emerges an artist far more cultured than he wanted people to believe. An admirer of Cervantes and his Don Quixote to the point of having dedicated a number of paintings to the novel (one of these, on loan from the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome, is on display). A connoisseur of ancient and modern painting: references to Gustave Dorè, Japanese prints, not to mention that Farinella has related his Youthful Self-Portrait preserved in the Pitti Palace to theself-portrait of Nicolas Poussin, and not to mention that Fattori, like other Macchiaioli, had been a careful investigator of the work of Piero della Francesca, of whom he evidently had to be reminded on several occasions (in the Acquaiole, for example, the compositional score reveals certain striking similarities with the Arezzo frescoes). A reader who not infrequently discussed his readings with friends: Ignited a commentary of his on Zola, for example, and even more pungent a discussion of The Betrothed with Diego Martelli, the critic who contributed decisively to the fortunes of the Macchiaioli, and whom Fattori considered the only friend he ever had (and on the literary echoes of Fattori’s painting, both incoming and outgoing, in the exhibition catalog attention should be paid to Silvio Balloni’s exhaustive reconnaissance, which is useful in expanding on Manganelli’s considerations that had compared Fattori to Federigo Tozzi and Renato Fucini).

As for the great painting of war subjects, the Livorno exhibition starts from the unquestionable realism of Fattori’s works, which had already been widely acknowledged to him by past critics (“When that realism is measured by the Risorgimento battles”, Roberto Tassi wrote in 1992 in reference to Madonna della scoperta, “it does not produce history painting but an immediate narrative, scattered, diffuse in its details, palpitating, not heroic, gray with sweat, dust, toil, a dramatic scattered and almost silent”) to convey the image, by now settled critically but perhaps not yet so well known to the public, of the deeply anti-rhetorical painter and, if not explicitly anti-Risorgimento, at least eager to tone down any celebratory tone, to make mincemeat of the truncated and solemn Risorgimento painting that abounded in the production of the various Cesare Maccari, Raffaele Pontremoli, Pietro Aldi, and Enrico Pollastrini himself. Fattori was not the only one in Italy to tell a kind of “private Risorgimento” (as the writer wished to call it in an article five years ago), but he was probably among the few, if not the only one, to tell it directly from the battlefields: no longer, then, a painting of epic clashes, of charges, of fighting, as much as, if anything, a painting of dust, a painting of the rear, a painting of soldiers rather than a painting of battles. Soldiers busy reading and writing letters, healing themselves after a clash, leaving the field. Soldiers, often, dead and abandoned in the field. It is a painfully human painting that, later on, would even border on anti-colonialist sentiment: another suggestion, this one, that the exhibition intends to offer the visitor, in the context of a renewed interest in the paintings that Fattori executed between the 1980s and 1990s basically to let people know what he thought of the colonial adventure in Ethiopia. Scholar Carmen Belmonte, who had previously written on these themes, does not hesitate to frame Fattori within the ranks of that anticolonial dissent of which, she says in her catalog essay, the painter was an “irritated and disappointed” interpreter of the betrayal of those patriotic and Risorgimento ideals in which he had believed in his youth. The exhibition therefore offers an opportunity to see a different Fattori than usual in this sense as well, with the presence of works that are rarely seen at exhibitions about him(Il soldato abbandonato and Pro patria mori, for example).

The Villa Mimbelli exhibition does not sidestep Fattori’s relationship with the Maremma (the comparison between the various versions of Bovi al carro, with also the comparison with the homologous painting by Giuseppe Abbati, is among the high points of the review), that with the other Macchiaioli, especially those of the second generation such as Niccolò Cannici and Egisto Ferroni, who Fattori disliked little because of their sentimentalism, and then the’ambivalent friendship with Plinio Nomellini, whom the old master could not forgive, in the professional sphere, for approaching Alfredo Müller, who was the most “impressionistic” of Tuscan artists (Nomellini’s spectacular Fienaiolo is on display, which, while paying homage, even rather blatantly, to his master’s Boscaiola , was already a work routed in totally different directions than Fattori’s). And he insists on several other themes, even to the point of taking the visitor to the last Fattori, to those “admirable years” of the early twentieth century, as Farinella calls them, to the extreme works that have often been forgotten as much by critics as by the jet-setting organizers of Fattori exhibitions.

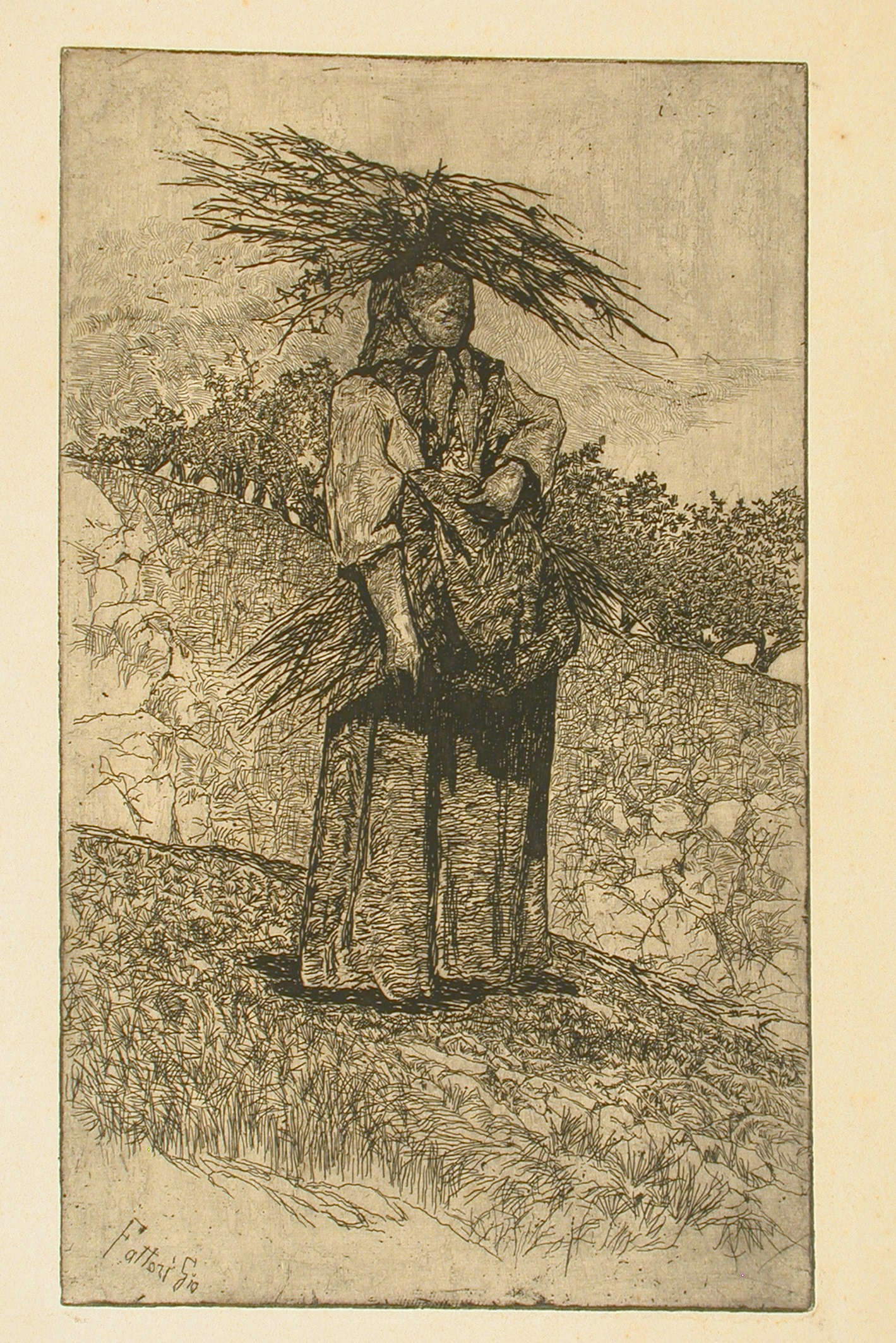

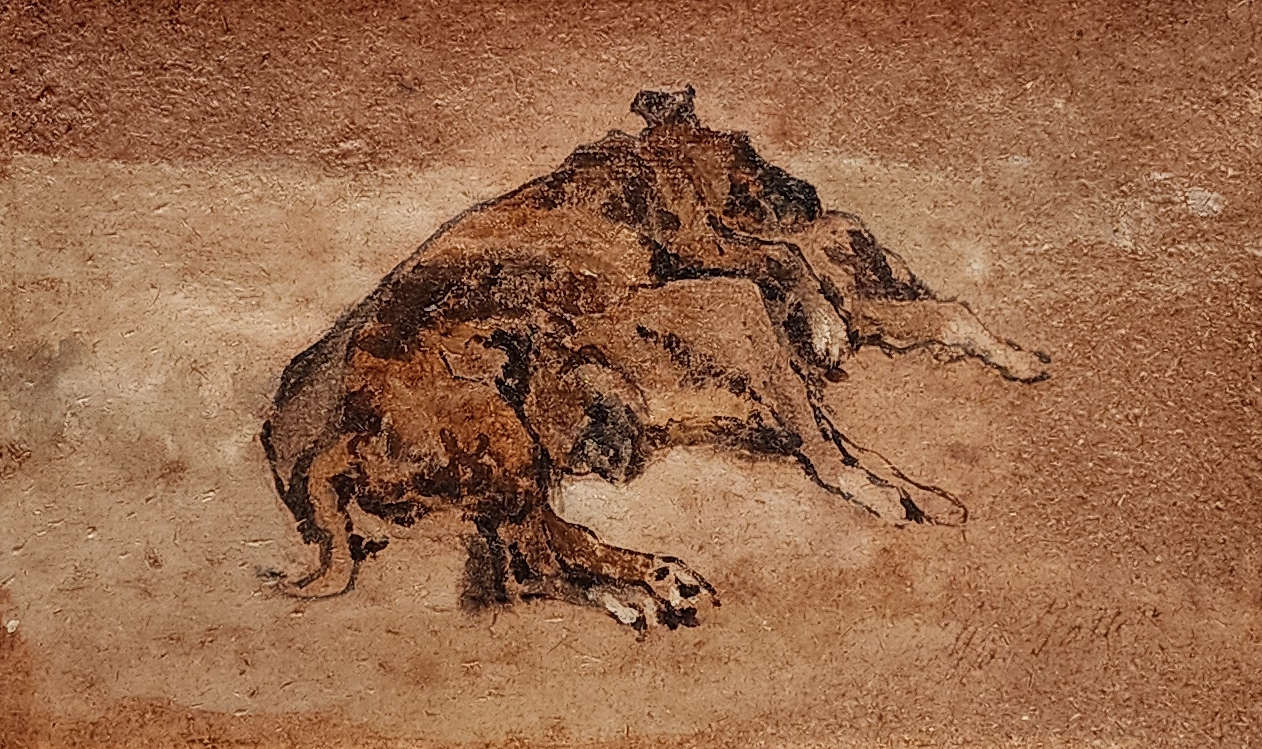

Giovanni Fattori was, fundamentally, a tired artist. Of everyone: of the clientele and the institutions, which had given him little satisfaction in his lifetime (although Fattori was perfectly aware that he practiced a painting that did not conform to the dominant taste). Of the public, which did not appreciate him (and again: Fattori, as early as the 1970s, had had no qualms about confessing to the dealer Carlo Amodeo that, in his opinion, “the public [...] most of the time is cretinous, and little the intelligent part”: as far as we know, he would not change his opinion). About politics. That of the last Fattori is, essentially, the image of an isolated misanthrope, surrounded by very few affections, and who does not, however, stop contesting, does not stop wanting to “break the balls to this rot that is society” (the firm, sincere purpose that twenty years earlier he intended to share with his friend Martelli), to experiment: here then are the war-themed paintings cloaked in lashing satire(Hurràh ai valorosi of 1907, one of the pinnacles of the last Fattori, sent to that year’s Venice Biennaleyear, where Nomellini’s Garibaldi could also be seen displayed alongside him in the exhibition), here is the social criticism with the tablets on the Maremma Workers, here are the engravings (superfluous, of course, to reiterate that the exhibition does not neglect the importance of this expressive medium, a salient feature of Fattori’s greatness), here is a work of literary inspiration such as L’affogato , which reveals an altogether unusual Fattori (“if we did not know the profound ideological rejection Fattori opposed to the dominant Symbolist aesthetic,” the curator writes, “we might almost think, for a moment, that the elderly artist had shown a fleeting sympathy with the ideals of which hispupil Nomellini had become an acclaimed spokesman”) and here are the paintings of animals, the living beings that perhaps most of all capture the old artist’s emotional participation (a portrait of a tired, old horse is Fattori’s last, unfinished painting). The very famous White Wall, a work from the 1970s, is placed at the close of the exhibition, together with the works of a varied group of artists who would have drawn more than a few cues from Fattori’s poetics, as an epilogue only seemingly counterintuitive, in reality functional to underline once again, on leaving, that profoundly revolutionary character of Fattori’s painting.

It must be said that there was already some awareness of this character when Fattori was still in full swing. As early as 1899, Diego Angeli, in Il Marzocco, could write that “revolutionary Fattori has always been in his painting, which next to the sappy graces of the traditional musketeers and operetta peasants who for many cheered the Florentine exhibitions, must have seemed the manifestation of a sentiment at least anarchic. For he never sought to embellish, with the lenocini of form and color, the scene that interested him and seemed to him worthy of being reproduced.” Fattori had bargained for recognition of a profound authenticity of intentions, had succeeded, and it was perhaps this sincerity that was considered, at the time, the most marked element of his rebellion. Then, thirty-eight years after Angeli’s article and twenty-nine after Fattori’s death, Longhi’s anathema, which threw Fattori and the whole Italian nineteenth century (“I do not believe [...] the definition of the ’stupid nineteenth century’ because it seems to me too extensive; but if it is a matter of reserving it for Italian painting of that centennium, I will only weakly oppose it”), practically relegated the Leghorn artist to the role of a side extra with respect toEuropean art, good at best for fashioning souvenirs of the Tuscan countryside, as it has been considered for too long on the back of the neglect of a servile, yielding criticism, prone to Longhi’s Francocentrism and its crude judgment on Italian painting of the time.

Paradoxically, Fattori’s recognition in Longhian times of night came more from outside than from Italy. Alpheus Hyatt Mayor, in 1971, considered him one of the greatest European etchers, as well as “the strongest Italian Impressionist,” and compared him to Manet. Norma Broude, in 1987, likened him to Degas and Cézanne and acknowledged that experimentalism in spatial construction that made him in fact one of the most original painters of his century. Albert Boime, in the 1990s, was among the first to mark with some clarity the divergences (and anticipations) from the Impressionist movement. In Italy, except for the few who devoted themselves to the study of Fattori’s painting, the Leghorn artist has always been in danger of being considered the illustrator of the Tuscan countryside. For in the meantime the public’s taste has also changed. So Manganelli’s suggestion, still valid today, was to take Fattori out of the national boundaries. Make him shed the role of the reassuring rustic painter, the grandfather everyone likes. To make him disliked. If, then, after the extensive monographic exhibition at Villa Mimbelli (which, in fact, relaunched the basis for the recognition of a European Fattori), we wanted to do Fattori a favor, we could start by thinning out the one hundred thousand exhibitions that our organizers put on every year and that, however, add little or nothing about him. little or nothing they add about him, but rather run the risk of reviving the cliché of the postcard painter, and one could think of an exhibition that frames Fattori in the context of European painting of the time. Fattori, Manganelli said, “needs to expatriate, needs coldness, arrogance, a hint of eyed dislike.”

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.