In one of the most intense passages of Gabriele D’Annunzio’s Il Piacere, namely the narration of the protagonist Andrea Sperelli ’s convalescence after receiving a nasty wound in a duel (an episode that marks the end of the first part of D’Annunzio’s masterpiece), it is said of the young count, pervaded by a quiet melancholy that “occupied his soul,” that “he saw in every aspect of things a state of his soul,” and that “the landscape became for him a symbol, an emblem, a sign, an escort that guided him through the inner labyrinth.” This dense page echoes a famous dictum of the Swiss philosopher and poet Henri-Frédéric Amiel, who in his nearly seventeen-thousand-page Journal intime, composed between 1839 and 1881 and published between 1883 and 1884(The Pleasure is from 1889, however), wrote that “un paysage quelconque est un état de l’âme, et qui sait lire dans tous deux est émerveillé de retrouver la similitude dans chaque détail” (“any landscape is a state of mind, and he who knows how to read them both will be astonished to find its similarity in every detail”). Amiel’s assertion that every landscape is a state of mind will have important implications and consequences for much late nineteenth-century art.

Amiel, defined by Cesare Segre and Carlo Ossola as a “popularizer also of Schopenhauer’s aesthetic thought,” adopted an effective formula that summarized the Schopenhauerian intuition of the correspondence between world and consciousness (“the world is my representation,” the German philosopher had said) and expressed on the one hand the reflection of external phenomena on the interiority of the individual, and on the other hand the ability on the part of human beings to project their feelings onto reality. The concept was, however, present in the arts and letters before Amiel popularized it: for example, in Vie de Henri Brulard, composed between 1835 and 1836 and published posthumously in 1890, Stendhal, wrote “landscapes were like a bow that played on my soul,” and even earlier, in a line from George Gordon Byron’s The Pilgrimage of the Young Harold, a work of 1812-1818, we read “I live not in myself, but I become / Portion of that around me: and to me / High mountains are a feeling” (“I live not in myself, but I become a part of that around me: and to me the high mountains are a feeling”). In the arts, a new sensibility toward landscape had been developing by the late eighteenth century: the idea of the representation of a foreshortened view governed by optical laws, the basis of Vedutism, had given way to a view painting more attentive to the atmospheric values and picturesque aspects of a landscape piece. Prodromes of this new sensibility could be read in the paintings of the Frenchman Claude Joseph Vernet (whose works in turn looked to the seventeenth-century art of Salvator Rosa and Claude Lorrain) and, in Italy, in Piedmontese landscape painters such as Pietro Bagetti (who, moreover, was already being compared to Vernet himself when he was just over twenty years old), Vincenzo Antonio Revelli, Giovanni Battista De Gubernatis and other artists working in the early nineteenth century.

This taste, at the origin of the poetics of the sublime, would be well summed up in Italy by Leopoldo Cicognara, when in his treatise Del bello he wrote that “the rosy dawning of day, the gilding of clouds and hills, the placidity of lakes, the immensity of the seas, the flickering light that shines on the meadows, form the patterns of beauty the most suave, equally as the rocks soaring over the sea, excavated by the beating of the waves, the storms, the winds, the forests, the torrents, the frost, the nights, present even in their horridness a beautiful and grandiose spectacle.” It would later be Caspar David Friedrich (Greifswald, 1774 - Dresden, 1840) who would express in the most accomplished, coherent and extensive manner the new consideration of human beings for nature: his tiny characters who, lost in the vastness of forests, facing the boundless sea or on mountaintops, contemplate the infinity before them, are one of the clearest signs of this new connection with nature, of this strong emotional tension, of the anxiety of Sehnsucht maturing in man forced to measure his finiteness against the greatness of nature.

Later there would also be those who, fascinated by reflections on the landscape-state of mind, would look for the roots of this sensibility as early as the Renaissance: this is the case of Angelo Conti (Rome, 1860-Naples, 1930), a physician with a passion for art (which later became his job), and who in 1894 published a famous essay on Giorgione, a painter who, in his view, was capable of going beyond the mere retinal datum and describe a nature pervaded by feeling (in an article written when he was only twenty-five years old, in 1885, and published in La Tribuna Romana, Conti wrote that “the artist transforms the true, according to his idea, the artist idealizes the true [...]. The artist in the presence of nature, chooses, among the multiplicity of appearances, the one that arouses an echo in his thought and feeling.”). And at the origin of the modern landscape, Conti placed The Tempest: “Giorgione,” he wrote, “is all here, in this force that chains him to the earth, and in this wide and deep music that he listens to in his inner self and that draws him away from the world.”

The landscape-state-of-mind debate began in Italy in the mid-1880s, but at the origins of the new landscape painting it is necessary to place, in addition to the insights provided by Amiel’s theory, those that Italian artists could draw from the paintings of Arnold Böcklin (Basel, 1827 - Fiesole, 1901): the Swiss, trained as a naturalist but fascinated by Romantic painting, had been able to infuse his landscapes with dreamlike, almost transcendental atmospheres, laden with symbolic references. The emerging Symbolist poetics had thus led him to create depictions that gave shape to an idea. One example is his famous series of the Villa by the Sea, with variants executed on several occasions between 1858 and 1880, inspired by the great painter’s Italian sojourns: a villa on the coast of Tuscany thus takes on a timeless dimension, evocative of Greek mythology, especially in a sunset version preserved at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt, where we see a figure (most likely a woman) gazing out to sea and who by some commentators has been identified as Iphigenia, the daughter of Agamemnon who, according to myth, was supposed to be sacrificed to Artemis to enable the ships of the Greeks to reach Troy and about whose fate there are several stories (in this case, the exegetes of the painting believe that it isIphigenia in Tauride and that the woman is therefore depicted on the coast of today’s Crimea). It is worth noting that Böcklin specified that he never thought of Iphigenia when he made the painting (however much mythology represented an important dimension for his art), but he said that this interpretation of his painting was not to be discarded: “everyone should consider the image in the world in which it speaks to him. It need not be exactly the same as what the painter imagined.”

It is then interesting to point out what forms landscape took in the art of Böcklin, who soon abandoned the naturalism of his origins to embrace a vision perfectly inscribed in Symbolist theory: as early as the late 1950s, “the landscape,” scholar Marisa Volpi has written, “becomes in him more and more the landscape of memory, we see over time a progressive contamination between dream and reality, between landscape drawn from one place and landscape drawn from another place.” One thinks of his most famous painting, TheIsland of the Dead, executed in five versions, the first of which dates back to May 1880 and is currently preserved in Switzerland, at the Kunstmuseum in Basel: a painting where dreamlike vision and nature come together, a painting filled with allegorical meanings, a painting that Böcklin himself intended as “a painting to make one dream,” to arouse different sensations in the relative, to give form to something intangible.

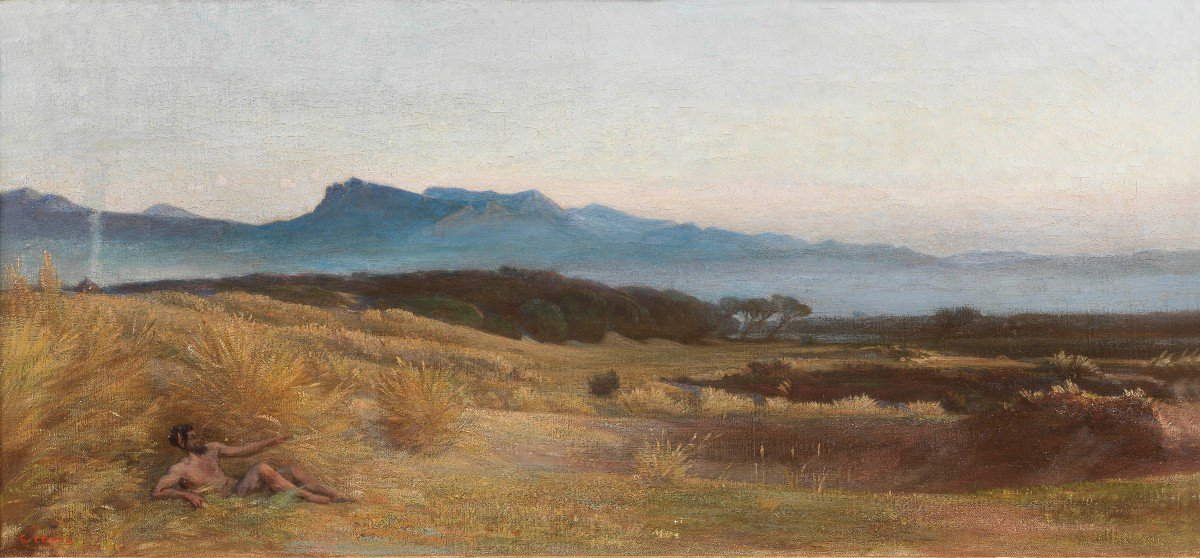

It can be said that from these cues, received in Italy at an early stage by Nino Costa (Rome, 1826 - Marina di Pisa, 1903) and the group In Arte libertas, Italian Symbolism had been born: Costa himself can be considered the most direct intermediary between Böcklin and Italy (the Roman painter had in all probability met his Swiss friend during the latter’s first stay in Rome). Costa nurtured an immense love for nature, which his contemporaries already recognized as a distinctive trait of his artistic personality, but he was especially attracted to what a view was capable of inspiring: “the true says nothing,” he had to say, “if it has not been seen through the feeling of thought.” It was a sensibility that had already been expressed in paintings that were closer to the truth, such as the famous Una giornata di scirocco sulle coste vicino a Roma at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Palazzo Pitti in Florence, where sentiment enters the view of the Latium coastline through the presence of the peasant who, bent by fatigue and with his step hindered by the blowing wind, carries a basket of fish: with that presence, the landscape takes on a totally different meaning and communicates to the relative the harshness of the life of the inhabitants of these areas in the mid-nineteenth century.

From the late 1970s Costa’s landscapes would then be charged with lyrical intonations capable of reflecting his panic sentiment, which was expressed especially in the views of the Apuan and Pisan coasts, in a sort of anticipation of Gabriele d’Annunzio’s lyrics that would evoke the same places: one of the most significant paintings (also for the same value that Nino Costa attributed to it), The Awakening of Nature, which had a long gestation, unfortunately no longer exists, as it was destroyed in London by a flood of the Thames (it was in fact purchased in 1896 by a group of British artists, donated to the National Gallery, and then transferred to Tate Britain). However, aDawn, from a private collection, which depicts the same piece of landscape, a view of the San Rossore pine forest at the mouth of the Arno, is still extant: in The Awakening of Nature, a solitary figure could be seen in this glimpse with a suspended and rarefied atmosphere, and which becomes an allegory of the “awakening” of nature, of regeneration, purity, and harmony. TheDawn was completed in 1877 and sold to the English collector Stopford Brooke, who wished to express, in a letter to Nino Costa, what the painting communicated to him: “this painting represents a world awakening, at that moment when nature has opened its eyelids at dawn, and has begun to acquire the consciousness that has awakened the joy, brightness and life of another day.”

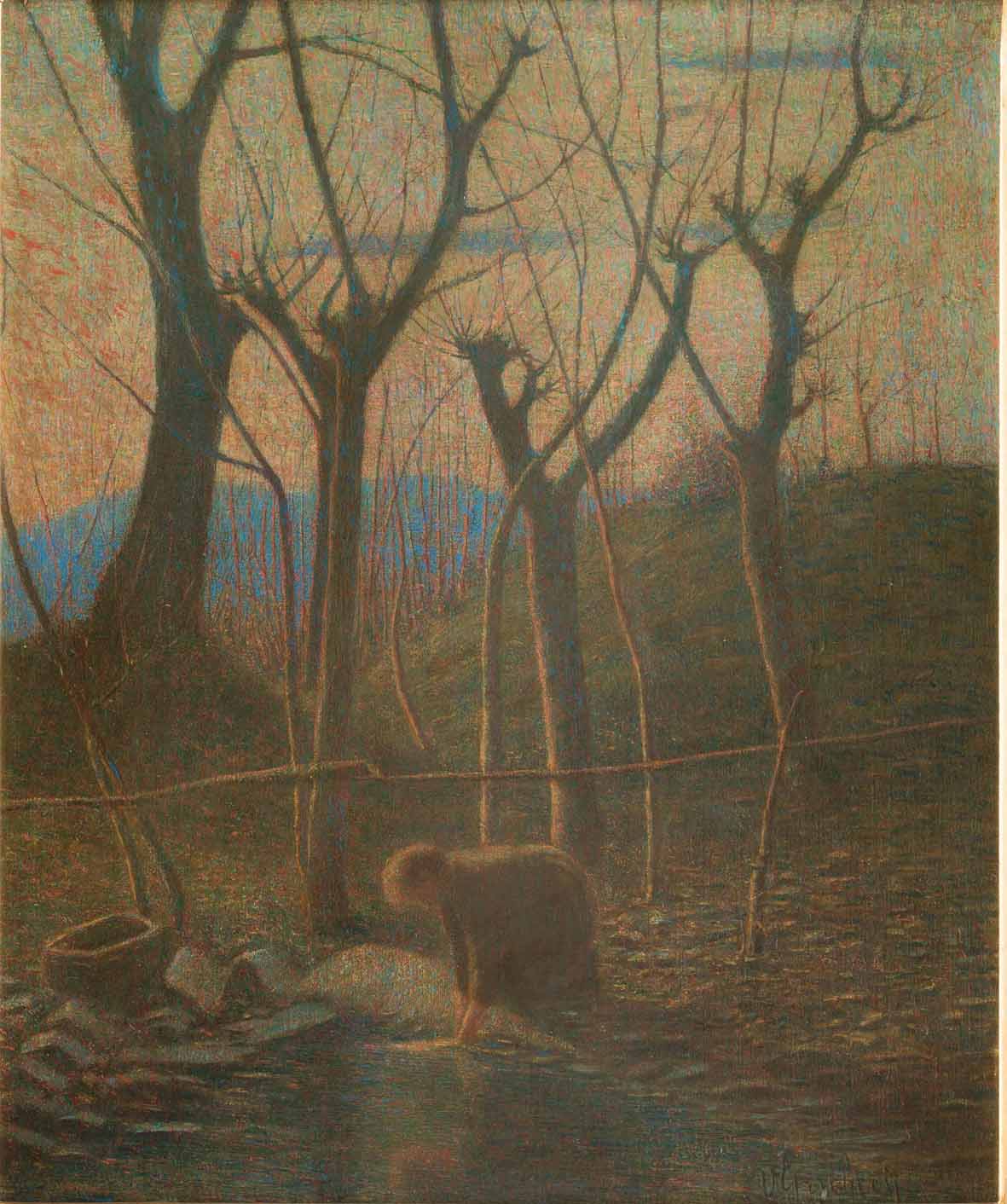

In her essay written for the recent exhibition States of Mind held in Ferrara in 2018, art historian Chiara Vorrasi wrote that the exhibitions organized in Rome by In Arte Libertas represented and the core of the spread of landscape-states of mind and that they were the basis of the different interpretations of the theme in Italian art. It has been seen how Nino Costa considered landscape according to a panic meaning of full fusion between man and nature that derived from his proximity to Böcklin: after the publication of Amiel’s Journal intime, other artists would seek different, renewed declinations of the landscape-state of mind. The renewal was spearheaded by gallery owner, artist and militant critic Vittore Grubicy de Dragon (Milan, 1851 - 1920), who in an article published in 1891 to defend from criticism the Divisionist artists who had presented themselves to the public for the first time at the first Brera Triennale, organized that year, had to write that “a painting is not a work of art if it does not reflect like a mirror the psychological emotion felt by the artist before nature or before his own dream.” And so “the most mature outcomes of his activity as a painter,” wrote Chiara Vorrasi, “are the result of a process of evoking memories, which appeals to acute sensory capacities to distill the most significant details, in a dense and evocative vision, in the wake of the theories of psychophysiology of which [...] he was also a fundamental popularizer.” Grubicy himself adopted pointillist techniques to create his landscapes: famous are the paintings executed in Miazzina, on Lake Maggiore, where the artist stayed for six consecutive winters at the end of the century and where he conducted continuous experiments on light effects, moments of the day, and the way in which atmospheric agents (Grubicy had a predilection for fog) modified the perception of a view. A painting now in the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Milan, known as Landscape, November, Evening (above Intra, Lake Maggiore), executed in 1890, can be considered the start of these investigations, which would later find their most lyrical peaks in paintings such as Sale la nebbia dalla valle or in the Winter Poem paintings: the result is a twilight minimalism that, Sergio Rebora has written, "comes close to Pascoli’s poetics and in particular to the overall atmosphere of Myricae,“ because ”the symbolic value identified in the elements of nature, the sense of expectation and mystery hidden in the small things of everyday life, the juxtaposition of auditory and visual images, the effects of synesthesia seem to find themselves in the respective inner worlds of the artist and the poet."

Other great Italian artists would participate in the same cultural climate. At least three are worth mentioning: Mario De Maria (Bologna, 1852 - 1924), Gaetano Previati (Ferrara, 1852 - Lavagna, 1920) and Giuseppe Segantini (Arco, 1858 - monte Schafberg, 1899). The former, close to the circles of In arte libertas and indebted to Böcklinesque poetics, would have found the dimension most congenial to him in urban views, especially those of Venice: the artist thus lingers on emptied and dreamy cities, illuminated by the moon, which, Vittorio Pica already observed at the time, was able to weave “conversations [...] with the greenish-gray walls of Venetian palaces,” devoid of human presence or nearly so, often tending toward the macabre, the horrific, the visionary. Still another approach is that of Gaetano Previati: here it is not the human being who projects his feeling onto nature, but are it is the real that imprints itself on the painter’s soul and gives rise to dreamed landscapes (“landscapes of the soul” to use an effective expression of Fernando Mazzocca), such as the Landscape of the Museo dell’Ottocento in Ferrara, or again like the Moonlight where all contact with reality is lost and the view takes on the appearance of an inner vision of the artist. Segantini instead uses luministic and atmospheric effects to charge his paintings with emotionality, as is the case in one of his most famous paintings,Ave Maria a trasbordo, a work of great poetic intensity that intimately describes a moment of calm and harmony on Lake Pusiano in Brianza, a painting in which the “sunlight, revered by the artist as the ’soul that gives life to the earth,’ is the source of a pantheistic and empathic vision of nature founded on the sacredness of life and the harmony between human beings and animals, a ’landscape state of mind’ in which the melancholy of eventide transcends into a feeling of universal peace” (Vorrasi).

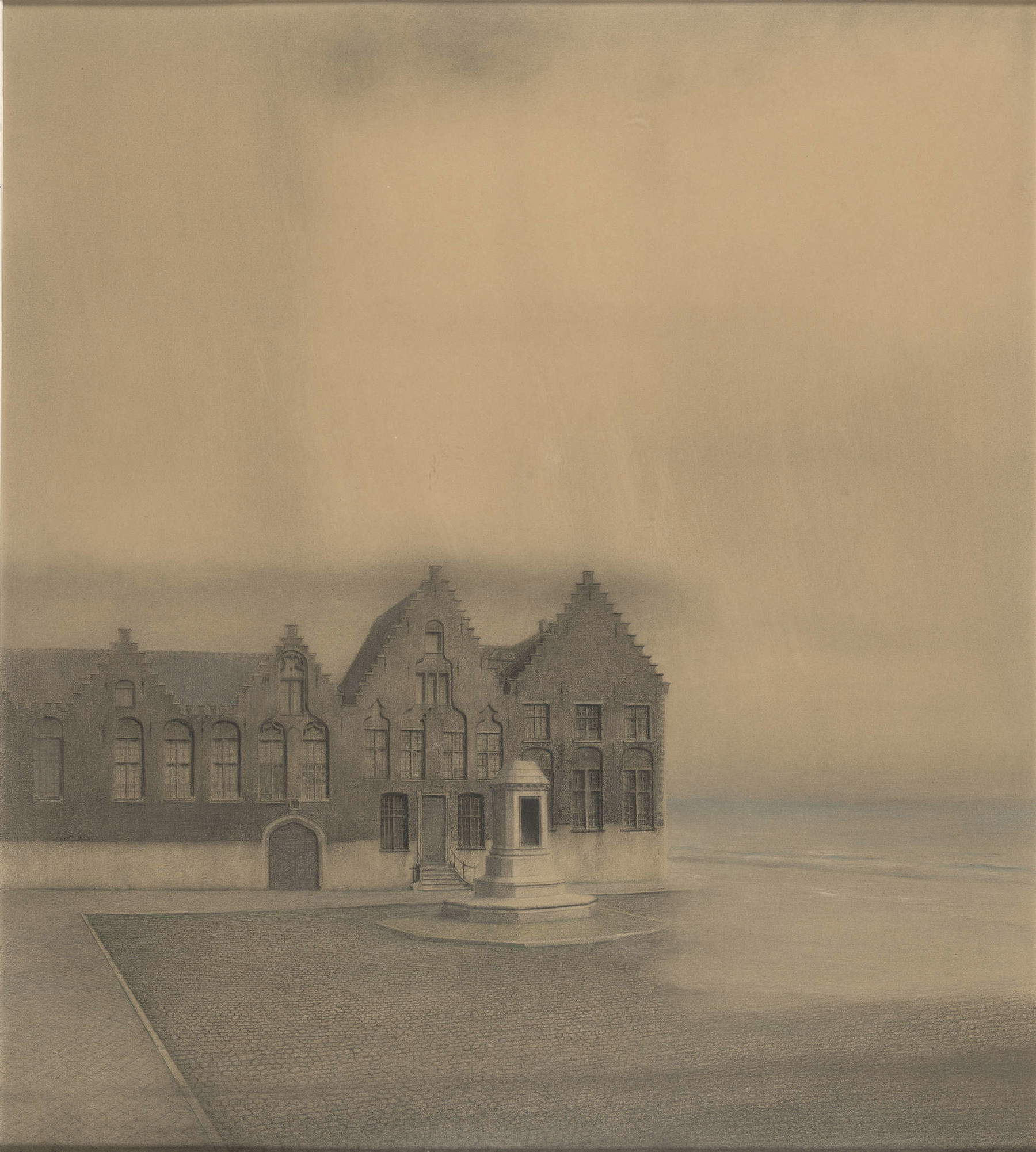

In the European sphere, the most interesting researches were those followed by the Belgian Fernand Khnopff (Grembergen-lez-Termonde, 1858-Brussels, 1921), who among the Symbolist painters outside Italy was the one who most frequented landscape painting (which represented one of the many souls of his varied, dense and almost always enigmatic production). His urban views, in this case those of Bruges, are to a certain extent comparable to those of De Maria: Khnopff’s peculiarity lies in the fact that his views are pieces of memory, fragments that had remained imprinted in his mind, since, for Khnopff, Bruges was the city of his childhood, where he lived from the age of two until he was seven or perhaps ten, according to known sources. The construction of the image of Bruges in Khnopff’s art was then influenced by a number of relevant influences, such as the Gothic revival that was raging in Europe at the time and that matched well with the appearance of the ancient Flemish city, and the reading of texts by the writer Georges Rodenbach (Tournai, 1855 - 1898), whom Khnopff knew personally through his brother Georges (also a writer). Art historian Lynne Pudles has used one of Khnopff’s most famous works, La ville abandonnée (“The Abandoned City”) as an example to point out the possible derivation from Rodenbach’s masterpiece, Bruges-la-Morte (“Bruges the Dead,” for which Khnopff also designed the cover): in a passage in his novel also dense with symbolic references, the writer describes a kind of retreat of the sea that would force the city to its death: “Bruges was its death. And his death was Bruges. Everything came together in a parallel destiny. Bruges was the dead one, herself buried by her stone banks, with the cold arteries of her canals, when she had ceased to beat the great pulse of the sea.” And according to Pudles, Khnopff wanted to give prominence to this image, which also returns in other works by Rodenbach: a cold, silent, deserted, empty city, pervaded by a feeling of death, an image intended to evoke the city’s sense of decay. In Khnopff’s paintings, it is the city itself that becomes a state of mind.

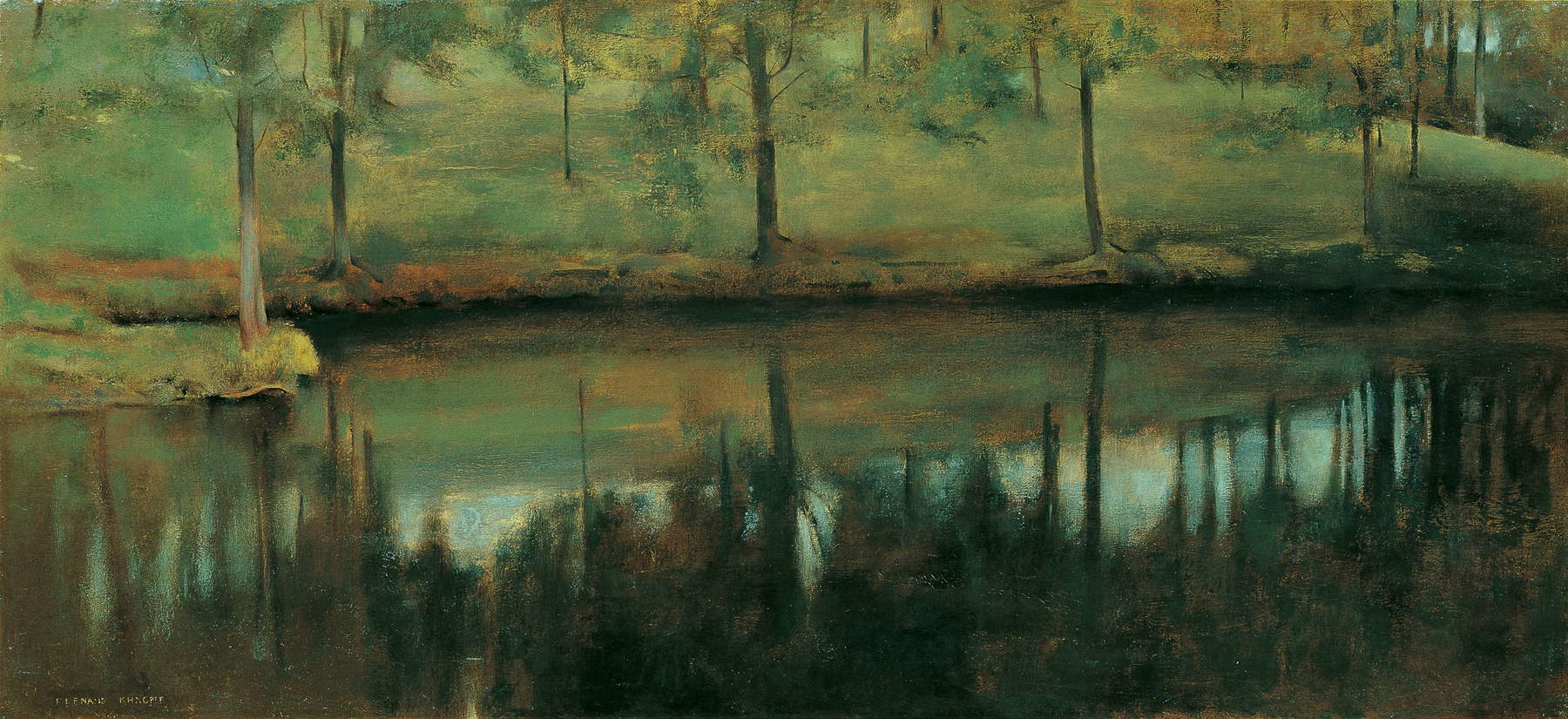

Khnopff’s landscapes also spring from his mind, equally linked to his memories: between 1880 and 1895, the artist produced a series of views of the woods and countryside around Fosset, a tiny rural village in the Ardennes where Khnopff’s family had a house in which they used to spend the summer. In these cases, too, the elaboration of the landscape follows the intimacy of memories, with the immediate consequence that the atmospheres are rarefied, the trees and the land are blurred and undefined, as when one is trying to remember something: few others like Khnopff succeeded in better communicating the impression of memory, cloaking it with a sense of deep melancholy.

Other artists, from Guido Marussig to Angelo Morbelli, from Giulio Aristide Sartorio to Gennaro Favai, would make their own contributions to the poetics of the landscape-state of mind. However, the season of the Symbolist landscape would soon come to an end, overshadowed by the entry of the avant-garde. However, the poetics of moods, and especially of emotions, also had some reflections in the forms of expression elaborated by the younger generations. Thus, it will be worth recalling how in the Manifesto of Futurist Painting, published in 1914, Boccioni, Carrà, Russolo, Balla and Severini, all at least twenty or thirty years younger than the artists mentioned above, would affirm that “the portrait, in order to be a work of art, cannot and must not resemble its model, and that the painter has in himself the landscapes he wants to produce.” The implication: “to paint a figure one must not make it: one must make its atmosphere.”

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.