Some careers seem designed by design: not because of lack of talent, but because of the lucidity with which everything happens. The debut at the right time, the right look, the right technique, the right face. And then, of course, the right connections. The parable of Anna Weyant, class of 1995, a Canadian artist now among the most discussed (and coveted) on the American scene, moves in exactly this direction. Like a perfectly oiled mechanism, she has established herself in the space of three years as a new voice in contemporary figurative art, but also as a perfect mirror of an art system that today behaves more like Russian roulette than a critical arena.

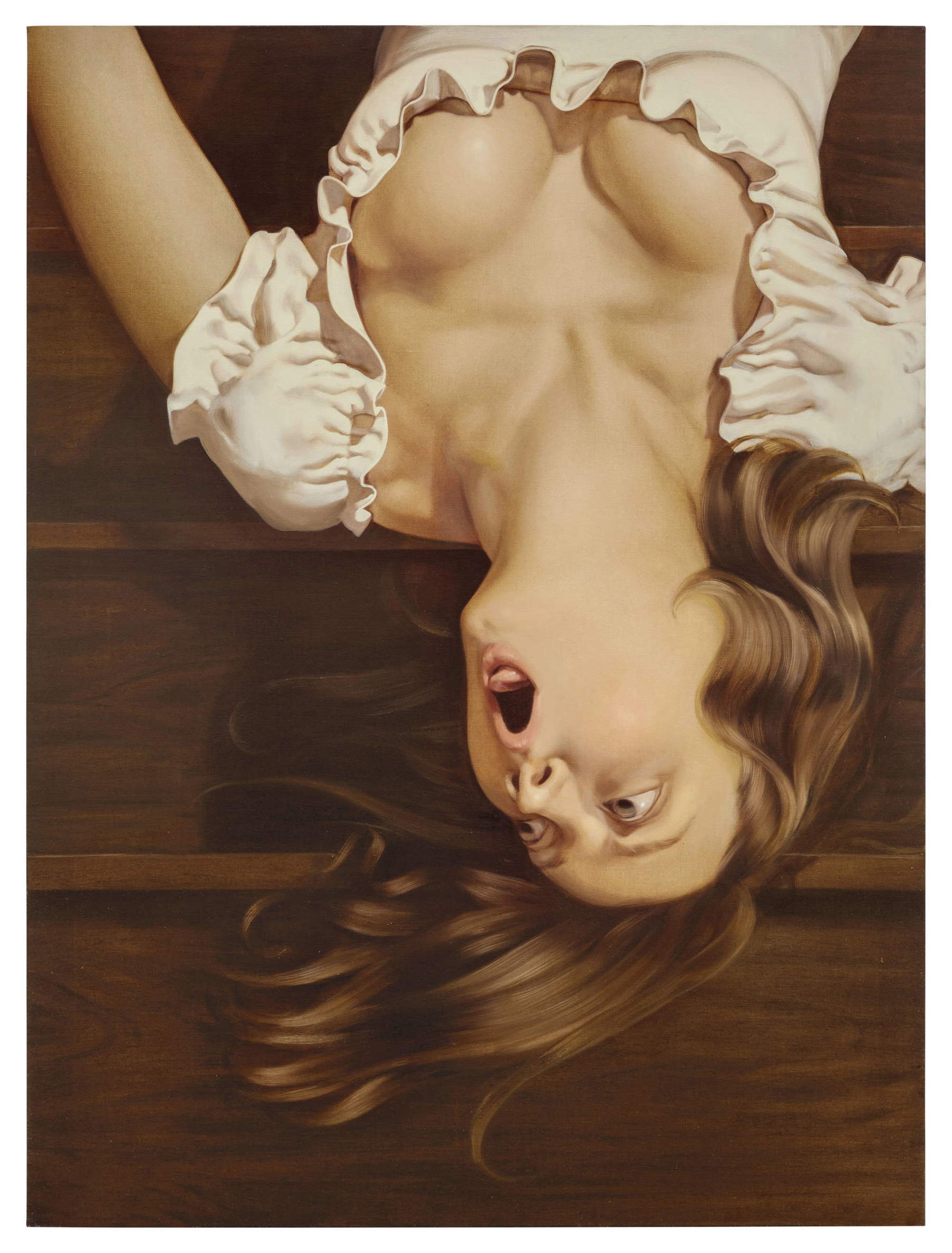

His works are impeccable, no one denies him that: the hand is precise, sure, the composition calibrated. Weyant looks to the masters of the Dutch seventeenth century as to John Currin, but manages to distill their lessons into quiet, melancholy images, familiar little theaters in which young women move, always a little tired, always a little fragile. The tension never explodes. It remains there, under the skin. As in the works Falling Woman (2020) or Loose Screw (2020), everything is held in balance, even when a figure plummets or a bandage covers a face. But it is precisely this perfection that challenges the most attentive viewer. Where does sincerity end and performance begin? How much is truly urgent, authentic, and how much is strategically marketable?

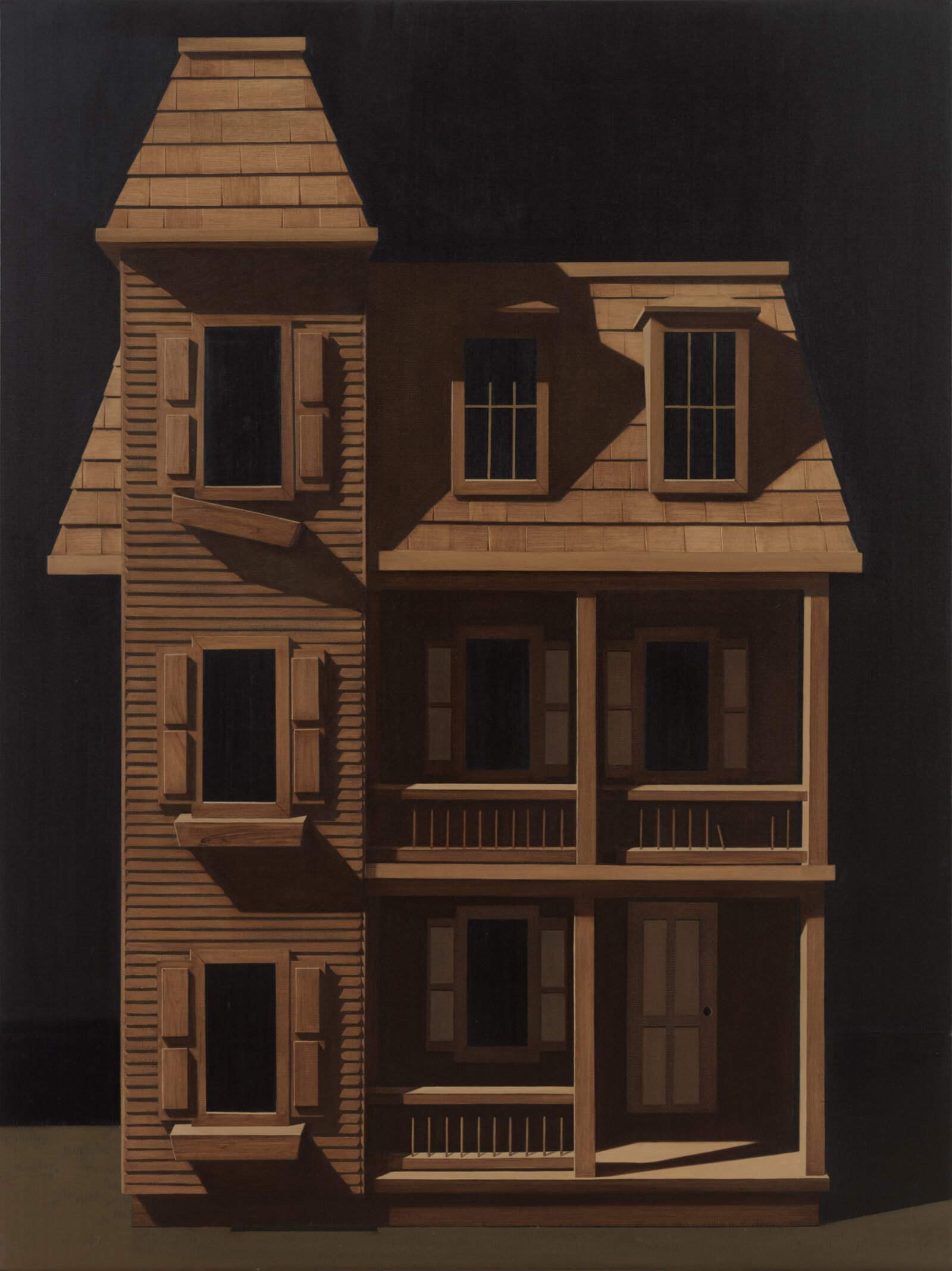

There is a house, a real one, in Weyant’s work. A dollhouse that the artist builds and then paints, as in House Exterior (2023). Small, middle-class, American: it looks like an icon of domestic security. But also a trap. Weyant’s art is all about this double bottom line: what looks innocent is only a reflection of something that has lost its purity. The bodies, for example, look almost like mannequins: delicate, young, bent in languid poses, never really active, always observed. The woman, here, is always seen, but never looking. The painting thus becomes an object: beautiful, lucid, restless. But also tremendously perfect for the market. And indeed.

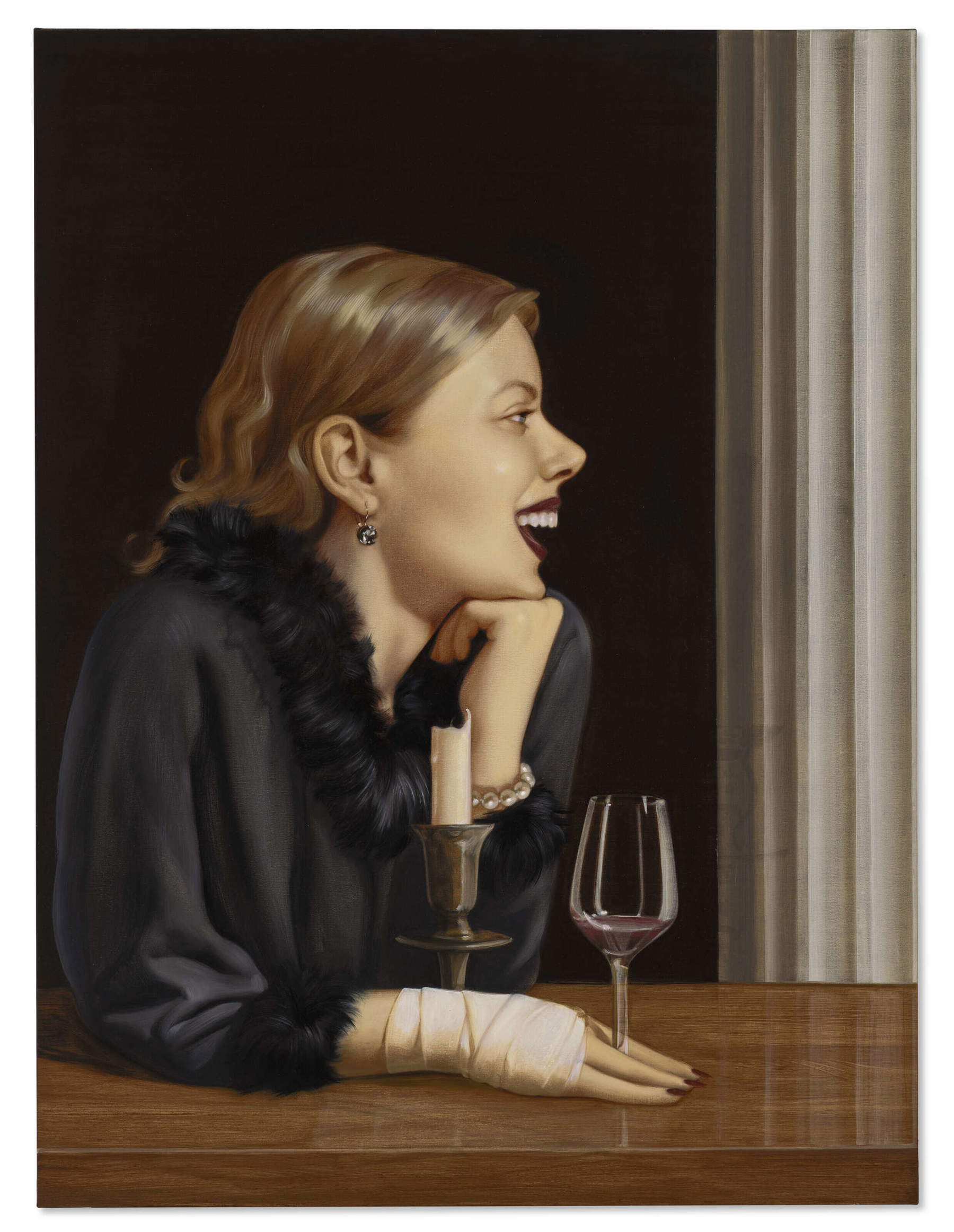

Weyant found herself, they say, in the “right place at the right time.” A formula that hides, in fact, a very precise geometry: New York, Canadian bourgeoisie behind her, classical studies, the photogenic gaze, refined visual culture, and access to a world of high relationships. Weyant had it all: talent, no doubt, but also the social and emotional capital on which the art system greedily feeds. And then, one cannot avoid mentioning, the relationship with Larry Gagosian, the world’s most powerful art dealer. A private fact? Perhaps. But art today can no longer pretend that biography is not part of the work. The result? Skyrocketing prices. A debut from $400 to $1.62 million within a few auctions. And an audience that, in part, seems more attracted to the media figure than to the work itself.

All great. But Weyant’s art does not break through. It is as if everything is kept at a distance. Emotions are suspended, never quite granted. Even melancholy, though it is omnipresent, seems tamed, functional. The titles are ironic, the color is calibrated, the compositions more reminiscent of a showroom still life than a lived scene. Perhaps this is what they like so much: an aestheticized, inoffensive trauma. Almost Instagram-like. Yet, behind this composure, a paradox broods: Weyant’s painting pretends to talk about wounds, but heals before it even cuts. It is a highly polished mirror that, however, reflects only surfaces. The point then is another. Weyant is not just an established young artist: she is a case study. Not so much because of the gossip about Gagosian or the explosion of her prices, but because she perfectly embodies the new rules of the game. A game in which art is content, product, identity, relationship, algorithm.

And this is where the real critical question opens up: are we looking at a talent who has been able to lucidly interpret the system or at alucky apparition, perfectly embedded in a self-feeding device? Is this art, or just the simulacrum of what we now call art, with all the required vocabulary and rituals? This is not to discredit Weyant. Far from it. Her works are refined, her poetics recognizable, her visual world strong. But that is precisely why one must watch her carefully: it is no longer enough to paint well to make incisive art. Art, today, must come to terms with its role in the market, in communication, in the attention economy.

Weyant, consciously or unconsciously, shows us the polished face of a system that works even too well. A system where, sometimes, context matters more than gesture. More than the truth, the staging. In the end, who really won: the painter or the machine that made her an icon?

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.