At the gates of Cairo, on July 21, 1798, the French army led by Napoleon Bonaparte (Ajaccio, 1769 - St. Helena, 1821) came into conflict with the Mamluk troops in what would go down in history as the Battle of the Pyramids, an episode that from the beginning assumed a powerful evocative value. Indeed, it is not surprising that art history has returned numerous depictions of the general onEgyptian soil, often complex and loaded with meaning, capable of restoring the ambivalence between military glory and historical reflection. The Neoclassical and Romantic periods, in particular, made Bonaparte a popular figure, portrayed in different aspects. First, as a triumphant leader. Beginning in 1797, when his military triumphs began to resonate, Napoleon is in fact portrayed as a hero, in poses similar to the sculptures and busts of Greco-Roman antiquity, such as those of Julius Caesar and Antinous, lover of the emperor Hadrian.

Prominent among these reproductions are depictions of the campaign in Egypt, a period between 1798 and 1801 that restores the figure of the general through works that frame his strength in the Battle of the Pyramids and the everyday moments of Bonaparte’s eastern journey. His portraiture is therefore aimed toward the desire to immortalize himself as an indomitable leader. The works emphasize his greatness and ego. Indeed, for Napoleon, the war effort in Egypt became a symbol of personal glory. Compositions depicting the expedition were created during the period of the empire, as evidenced by Battle of the Pyramids by Francois-Louis-Joseph Watteau (Valenciennes, 1758 - Lille, 1823), painted between 1798 and 1799, and which seems to reflect the influence of the illustration dating from 1803 by Dirk Langendijk (Rotterdam, 1748 - 1805) and the sketch by François-André Vincent (Paris, 1746 - 1816). The scenario narrated in Watteau’s work describes the best-known battle of the campaign, which was fought on July 21, 1798, and saw the French army led by Napoleon, against the forces of the Mamluks led by Murād Bey and Ibrāhīm Bey. For the occasion, the future emperor of France unveiled one of his most interesting military techniques: the great divisional square, an innovative strategy that enabled him to maintain an impenetrable defense against enemy cavalry and marked a turning point in the military tactics of the time. In Watteau’s painting, the battle scene is silhouetted beneath the imposing pyramid painted in the background of the picture.

The portraits of Napoleon depicting him in Egypt are mostly drawings and sketches made by the artists who accompanied him on the expedition, as in the case of Charles Louis Balzac and André Dutertre. Around 1867, the latter sketched a series of works capturing General Bonaparte’s army in the streets of Cairo and in the sands of the desert. Dutertre, among the protagonists of the great Napoleonic enterprise, was accepted into the Institut d’Égypte in August 1798, within the section devoted to literature and the arts. During that period he drew 184 portraits of the expedition’s members, including scientists and officers, whose images now make upReybaud’s Histoire scientifique et militaire and illustrate Villiers du Terrage’s Journal. In addition to the evocation of the men of science and war, Dutertre also turned to the locals, struck by the souls and colors of the people.

There are actually several artists who depict Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign: many depict him standing in front of the imposing Mamluk ruins of the City of the Dead, while others immortalize him on horseback ready to scan the city of Cairo and the ancient ruins of Giza. From 1835 is the work by Léon Cogniet (Paris, 1794 - 1880) entitled L’Expédition d’Egypte sous les ordres de Bonaparte. In the context of the military and scientific campaign, the figure of the commander is elevated to military leader and promoter of a cultural and intellectual enterprise. The expedition is a key historical moment in the connection between the ancient and modern worlds. Indeed, through the campaign, Napoleon succeeds in validating both the link between Pharaonic Egypt and the Enlightenment aspirations associated with the new century. In Cogniet’s painting, now in the Louvre Museum, General Bonaparte appears as both a commander and a man of culture surrounded by scientists, archaeologists, artists, and military personnel.

With his determined gaze he directs search and excavation operations, while inside the painting archaeologists intent on uncovering a sarcophagus are glimpsed. Indeed, the work that sees the link between war, research, and study reflects Napoleon’s idea of making his expedition a mission of knowledge as well as power. Can it be a challenge of vanity and greatness? Absolutely so. In 1851 the Swiss Karl Girardet (Le Locle, 1813 - Versailles, 1871) produced the engraving Napoléon en Egypte (Quarante siècles le méprisent). The scene depicts the moment when Bonaparte on horseback stands before the enigmatic sphinx and pyramid, witnesses to a lost Egypt. The title of the engraving Forty centuries look down on him from on high recalls beyond that a phrase (attributed to Napoleon) uttered before his army, “Soldiers! From the top of these pyramids, forty centuries of history are watching you.”

In 1895 Maurice Henri Orange (Grandville 1868 - Paris 1916) illustrates this in his Napoléon Bonaparte devant les pyramides, contemplant la momie d’un roi in the intent to observe the mummy of a pharaoh. We can therefore define the work as a silent conversation between the French general representative of modern, Western power, and the holy ruler of Egypt. The scene is captured by director Ridley Scott within the 2023 film Napoleon. In the film adaptation, Bonaparte, played by Joaquin Phoenix, contemplates the mummy in the sarcophagus sensing, probably for the first time, the grandeur of Egyptian culture. Following Orange’s model, Scott captures with the same intensity the instant when Napoleon approaches the mummy to scan its face carefully. He rests his hat on the sarcophagus with a gesture of curiosity, then picks up a wooden crate and moves even closer, seeking in the mummy’s eyes a comparison.

Can Napoleon actually hold that gaze? We don’t know, but in the depictions of the Egyptian period, the figure of Bonaparte is delineated as a hero immersing himself in a dialogue of conquest with an immortal Egypt. He rises in deep contemplation of those lands. Dutertre’s Napoleon reflects on this very thing. He reasons about its grandeur and that of a civilization that lives on in the memories of its ruins and the majesty of its past. On the historical level, the French expedition to Egypt responded to precise colonial ambitions: Bonaparte aimed to weaken British influence in India by striking at its economic interests through control of the eastern Mediterranean.

Therefore, in addition to assembling a massive army of about 50,000 soldiers, Bonaparte sent more than 160 scholars, members of the Commission des sciences et des arts, from various disciplines that included botany, geology, and the humanities, to join the enterprise. The experts devoted themselves to carefully exploring and documenting Egypt’s cultural and natural landscapes, producing in 1809 an encyclopedic publication called Description de l’Égypte ou Recueil des ob- servations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Égypte pendant l’expédition de l’Armée française(Description de l’Égypte, orthe collection of observations and researches made in Egypt during the French army expedition) which contains detailed descriptions, including those of the pyramid complex at Giza. Accounts left by members of the commission allow historians today to confirm that Napoleon visited the Pyramids, although it remains unlikely that he attributed their strategic importance from a military point of view.

According to Salima Ikram, professor of Egyptology at the American University in Cairo, Napoleon had great admiration for the sphinx and the pyramids, even using them as symbols to motivate his troops toward greater personal vanity and glory. For this reason, contrary to what is possible to see in Scott’s transposition, Ikram emphasized that Bonaparte could never have fired at them. In an interview with The Times, Scott himself said “I don’t know if he did,” referring to the alleged cannon shot at the sphinx attributed to Napoleon’s troops visible within the film, later adding that the narrative was a quick way to symbolize the leader’s conquest of Egypt.

During the expedition, in the fervor of cataloging Egypt’s archaeological riches, French scholars appropriated treasures and artifacts from the Pharaonic lands, including the Rosetta Stone, a slab of granodiorite stone engraved in three languages weighing about 760 kilograms, crucial in deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphics. For Andrew Bednarski, a scholar specializing in 19th-century Egyptology and history, there was in fact a genuine interest among scholars, shared even by Napoleon, in understanding aspects that Europeans had not had access to since classical times.

Although it ended in military failure, Bonaparte’s expedition helped spread a deep interest in Egyptian civilization in Europe, triggering a wave of Egyptomania that would take over the world. And so it did. With the end of French rule in Egypt in 1801, many of the relics including the Stele itself ended up in the hands of the British despite the fact that by that time Napoleon had returned to France. The desire then to possess the artifacts of ancient Egyptian civilization opened the door to centuries of excavations, trafficking and raids, which stripped Egypt of its memories. From the Napoleonic invasion onward, a flood of artifacts left Egyptian soil, often through clandestine routes.

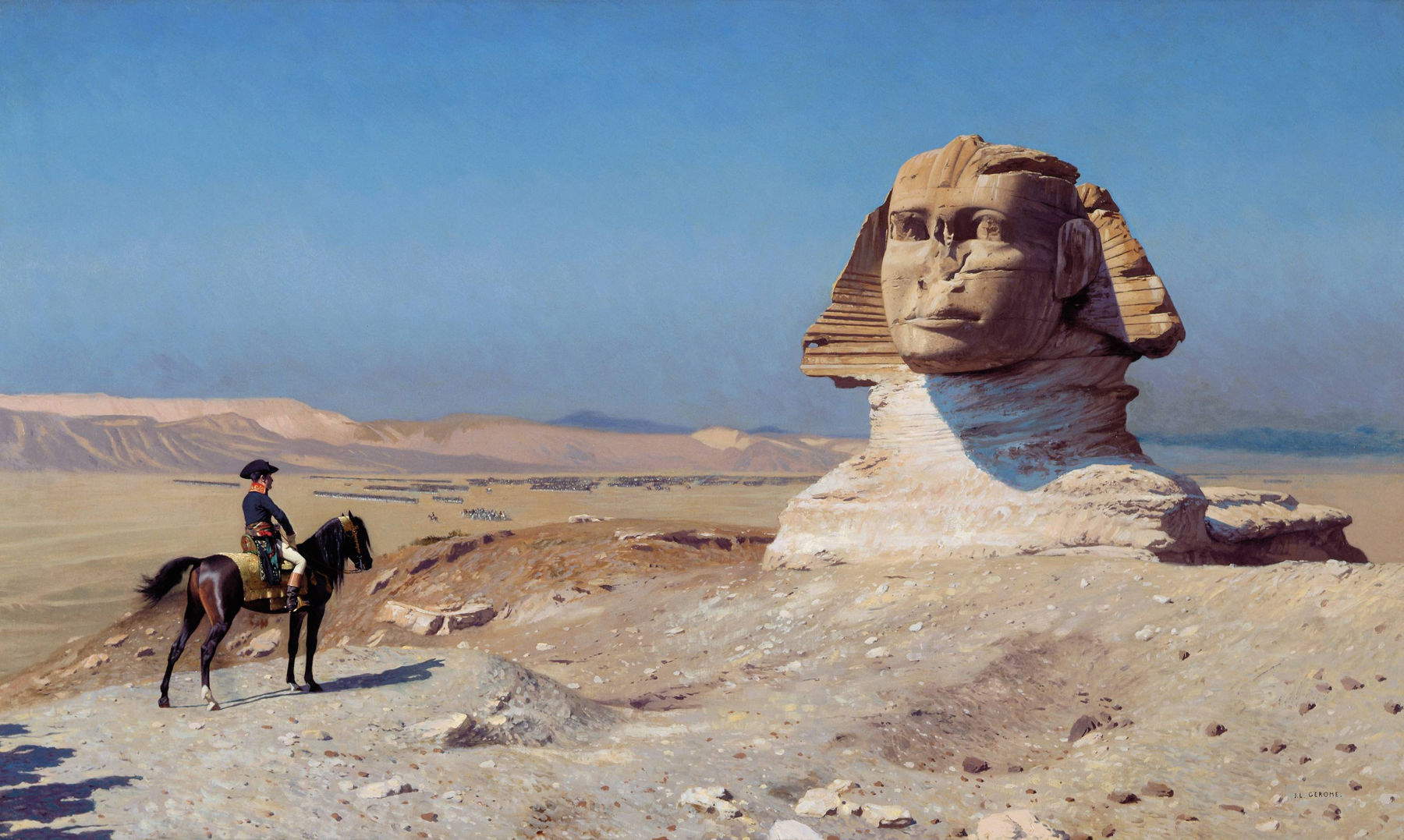

According to Alexander Mikaberidze, a professor at Louisiana State University in Shreveport and an influential scholar of Napoleonic history, the Egyptian campaign, although it ended in military defeat, produced important scientific and cultural effects. Indeed, the invasion marked the beginning of a new season of interest in Egypt, giving impetus to the Western fascination with the pharaonic civilization that would guide studies and explorations in the following decades. Beyond that among all the artists who portrayed Bonaparte, the figure of Jean-Léon Gérôme certainly stands out. The French artist was familiar with Egypt and, having explored its lands on four occasions since 1855, knew what he was doing. The painting Bonaparte devant le Sphinx made between 1867 and 1868 can be considered the most representative painting of the Egyptian Napoleonic period. With a strong visual impact and great scenic power, in the work the sphinx dominates half the canvas by rising above Bonaparte motionless in front of it.

As is often the case in Gérôme’s art, it is the framing that gives depth to the scene. The pyramids are deliberately excluded to enhance the clash between man and millennia-old stone. Gérôme, a master of capturing the moment, thus succeeds in freezing time although small details manage to foretell its imminent resumption: the horse’s tail barely vibrates, the shadows of a staff are outlined in the left corner of the painting, and in the distance in the desert troops move ready to participate in the 1798 battle of the pyramids. Gérôme first presented the painting titled Oedipus at the 1886 Paris Salon and through the figure of the sphinx drew a subtle link between the mythological hero of Thebes and the one who would save France. Ridley Scott pays homage to Gérôme’s work with the same framing. The artist’s works addressing Bonaparte’s expedition to Egypt are diverse. In 1867 he painted Le Général Bonaparte et son état-major en Égypte. The scene takes place in the desert, with a proud Bonaparte riding a camel in the center of the scene and surrounded by his officers. In the work, the artist emphasizes the exoticism of the setting through the detailed depiction of the Bedouins’ colorful costumes, the landscape, and the characters’ posture. Contemporary with the date of 1867 and 1868 is the additional oil work Bonaparte en Égypte. Once again Gérôme, depicts the leader standing firm and proud in front of the Mamluk tombs outside Cairo.

Thus, on his horse in front of the colossus immortalized by Gérôme, Napoleon scrutinizes his fate. After his defeat in Egypt, his arrogance bends to the eternity of Egypt, as the pyramids, obelisks, and temples that have withstood the centuries remain there in memory of how fragile and transient his and men’s existence is.

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.