Forty years have passed since, in 1981, Franco Maria Ricci published one of the craziest works of the twentieth century, Codex Seraphinianus by Luigi Serafini (Rome, 1949), the mysterious and enigmatic collection of plates that made up an encyclopedia of images written in an alphabet invented by Serafini himself, and which, however, is asemic, that is, it does not transcribe any existing or imaginary language. A surreal work around which the attentions of many critics have been focused, Codex Seraphinianus is now published in a new edition by Rizzoli illustrati (392 pages, 120 euros, ISBN 9788891832481), made especially for the fortieth anniversary of the Codex, and for which Serafini has executed seventeen new plates, with updated images, which are thus added to the historical ones published in 1981.

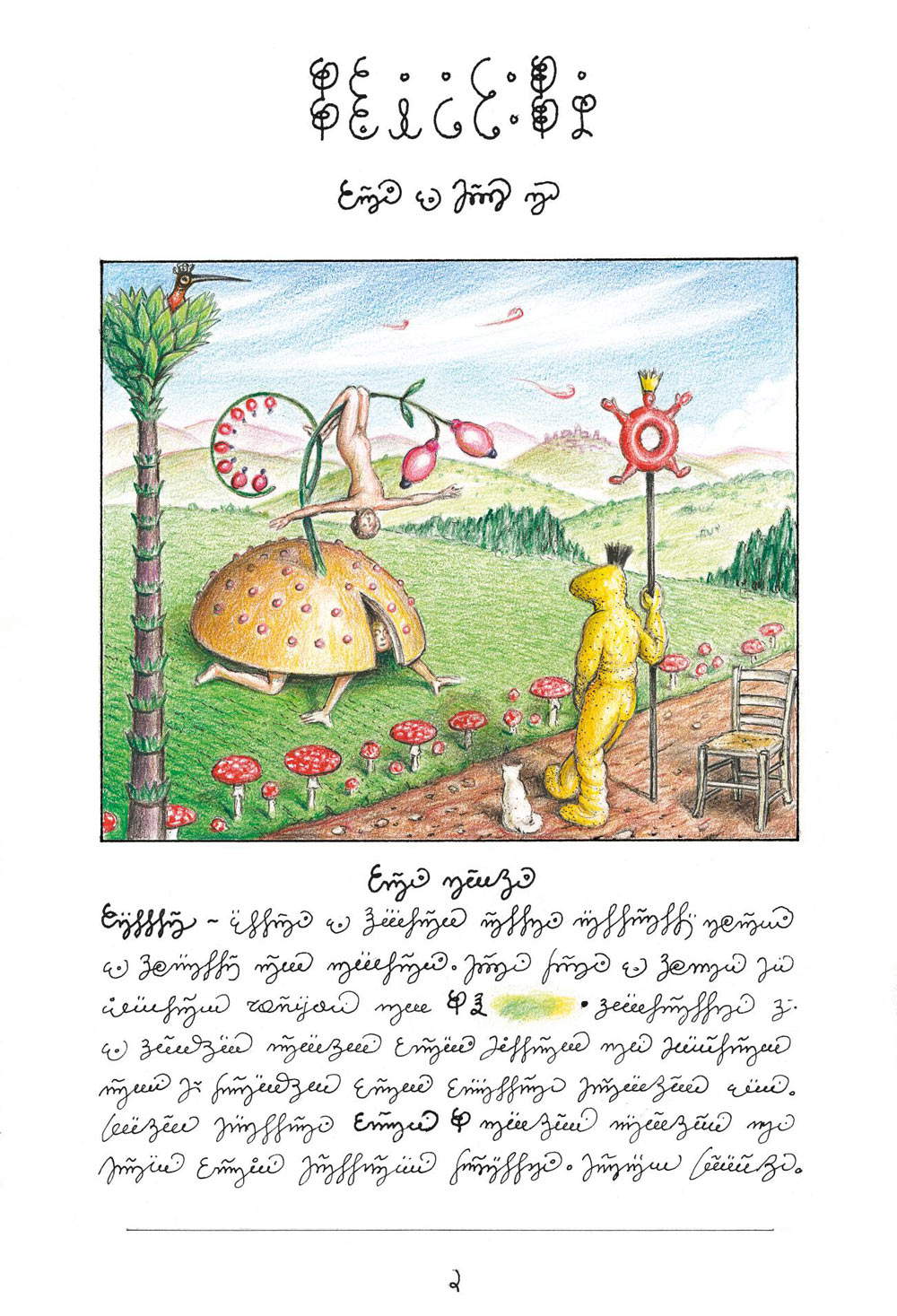

Codex Seraphinianus is a surreal encyclopedia, a succession of fantastic visions written in an invented alphabet, where subjects such as zoology, botany, physics, architecture, mineralogy, and ethnography coexist. In the bizarre world of Codex live strange three-headed birds (or birds consisting only of a large head, or only of legs), horses with wheels, crocodiles that are born from the metamorphosis of an intercourse between human beings, trees perfectly split in half, plants with strange flowers, absurd machinery. Divided into eleven chapters, Codex Seraphinianus takes its reader on a journey through an imagined world, described with an apparent scientific flair: in fact, the chapters are each devoted to a different topic (flora, fauna, bipedal creatures that do not belong to the animal world, physics and chemistry, machines, ethnography, history, writing, gastronomy, games and architecture).

All written in that alphabet that makes the plates instantly recognizable. “In the universe that Luigi Serafini inhabits and describes,” Italo Calvino, one of the Codex’s most enthusiastic critics, had written, “I believe that the written word preceded the images: this meticulous and agile and (we must admit) crystal-clear cursive handwriting, which we always feel a hair’s breadth away from being able to read and yet eludes us in every word and every letter of it. The anguish that this Other Universe conveys to us comes not so much from its diversity from ours as from its similarity: thus the writing, which might likely have been worked out in a linguistic area foreign to us but not impractical.”

Tablet of the new edition of

Tablet of the new edition of Tablet of the new edition of the

Tablet of the new edition of theFranco Maria Ricci had called Serafini “a modern amanuensis,” and his Codex an “intriguing and anomalous” masterpiece. For Vittorio Sgarbi, who followed its creation from the very beginning (this was the time when the Ferrara art historian was collaborating assiduously with Franco Maria Ricci: he would later become one of the most featured signatures on FMR magazine), it is a work of virtuosity that harkens back to the painstaking work of medieval and Renaissance illuminators. “Serafini,” Sgarbi recalled in one of his articles published in Il Giornale in 2014, “never ceased to amaze with inventions, and also with the extraordinary calligraphic perfection and almost perversion of drawing. What, in the span of three years, Serafini had elaborated was a veritable illuminated codex, an encyclopedia in the ambivalent sense of illustration and Enlightenment Encyclopédie.” Serafini’s alphabet, indecipherable, nevertheless seems to have been invented on the basis of Western alphabets: a script that therefore reads from left to right, with upper and lower case ,and complete with punctuation. However, Serafini himself stated at a meeting at the Oxford University Society of Bibliophiles that the alphabet does not translate any language and that his intent was, if anything, to put the reader in front of seemingly meaningless signs in order to give him the impression of being like children who stand in front of books when they cannot yet read.

It did not take long for Codex Seraphinianus to immediately become a cult object capable of fascinating artists, readers and critics, generating discussions about its meanings and origin. Even today it is still considered one of the most interesting contemporary artists’ books, not least because of its obvious timelessness. Admirers have included Roland Barthes (who read it in advance, when it had not yet been published) and the aforementioned Italo Calvino, who called it “the encyclopedia of a visionary.” With the advent of the digital age and new forms of communication, this book has gained even more relevance and uniqueness, and it is also for these reasons that Mondadori has thought of a new edition, celebrating the 40th anniversary of its first release.

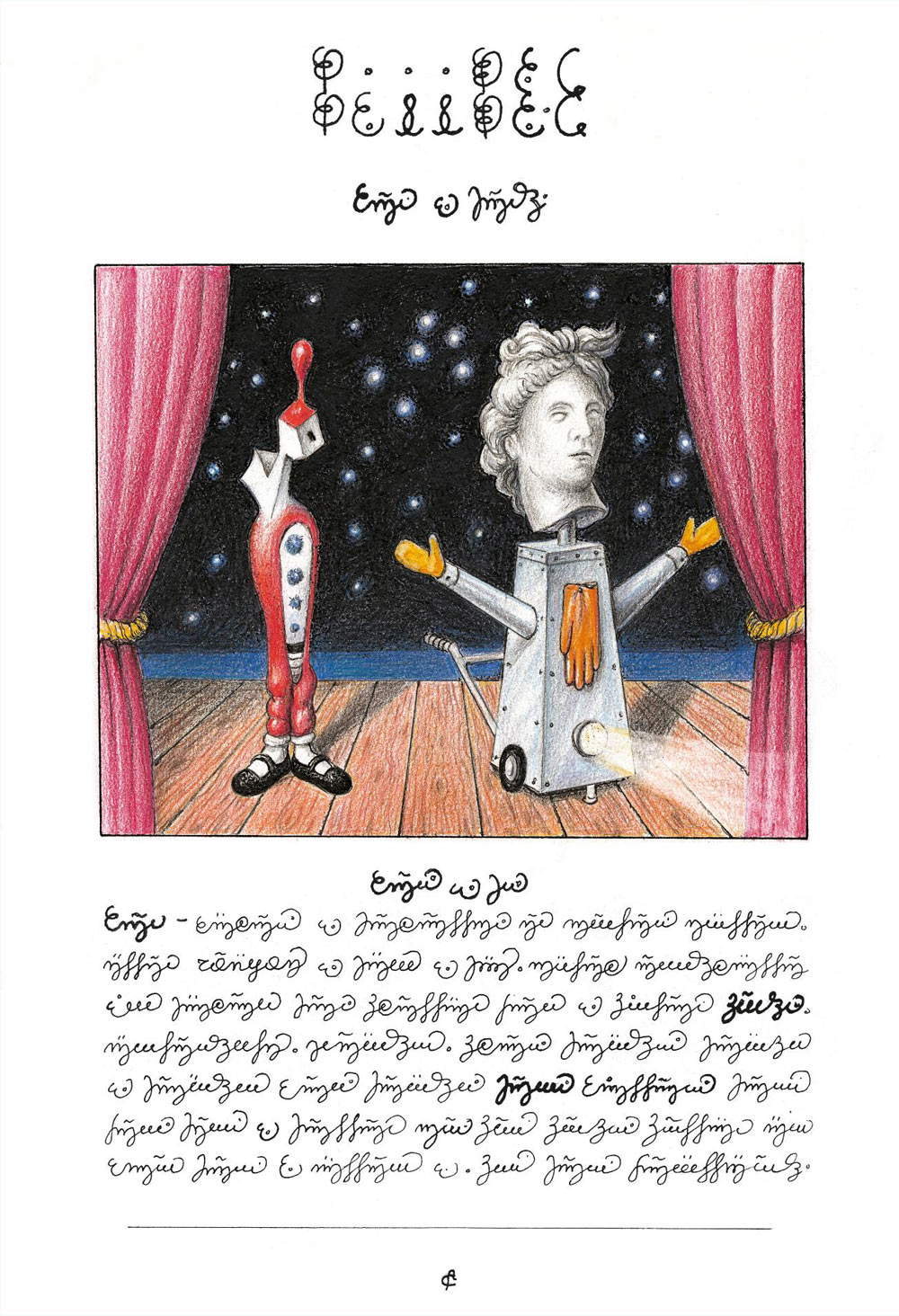

Luigi Serafini, for the occasion, designed a new packaging for the deluxe edition poised between art book and design object, and, as mentioned, also enriched the set of images with seventeen new plates. Among the images birthed from scratch by Serafini’s imagination are a fantastical building resting on a large walnut tree, images of strange constructions by the sea, men-fungus, a robot-mannequin à la De Chirico (complete with hanging glove, a trademark of the metaphysical painter), and much more. The Decodex, the booklet enclosed with the Codex where Serafini recounted the origins of his work, has also been updated: on the new Decodex plates we see a curious reworking of the Column of Marcus Aurelius where the statue of St. Paul at the top is replaced by a large clock, some strange figures arranged on the Spanish Steps of Trinità de’ Monti, various images of glimpses of Rome, as well as a photograph of the Carrot Woman, one of the Roman artist’s most famous sculptures, also exhibited at the Milan Expo in 2015.

A multifaceted artist who is difficult to pin down, Luigi Serafini, born in Rome in 1949, trained as an architect and has worked in Italy and abroad. He has illustrated writings by Franz Kafka and Michael Ende, but his first major work, started as early as 1976, is precisely Codex Seraphinianus, published, as recalled, in 1981 by Franco Maria Ricci and since 2006 in subsequent editions. Today, the original plates of the Codex are kept at the Labirinto della Masone museum in Fontanellato, the place of Franco Maria Ricci’s dreams where a room shows visitors the original fruit of Serafini’s imagination. Serafini also worked as a set designer and as a film illustrator (he designed the first playbill for Federico Fellini’s La voce della Luna ). In 2007, the Pavilion of Contemporary Art in Milan dedicated Luna-Pac, a highly successful ’ontological exhibition’ to Serafini. From October 10, 2020 to January 2021, the Centre régional d’art contemporain (CRAC) in Sète in turn dedicated an exhibition to the surrealist universe of Codex and its author.

|

| A new edition for Luigi Serafini's Codex Seraphinianus. With 17 new plates |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.