by Giuseppe Adani, published on 17/02/2021

Categories:

Books

/ Disclaimer

Review of volume VIII of the "History of Parma," entirely devoted to the Art History of the city in the centuries from the 16th to the 20th.

As neve al sol si disigilla sings Dante at the climax of his Paradise: so at the end of this perilous winter a blazing sun rises over Parma to sprinkle the city’s entire life, its awareness of being an incomparable place for art of all times. This is not hyperbole! Already Enrico Bodmer in his work on the painters of Emilia took the cue by saying “no country like Italy possesses a landscape of such luxuriant beauties,” and in describing them he pointed to this region where a chain of cities, “defended by walls and towers,” presented itself as a continuity of privileged forges of art and culture. With good reason he then discovered a particular one, truly dazzling. Today the imposing volume forming part of the “History of Parma,” which is devoted to the History of Art in the centuries from the 16th to the 20th, is truly the illuminating star of an incontrovertible reality.

The foreboding reader will follow my singular advice, at least in comparison with many publishing titles in which written introductions have an already taken for granted flavor of ritual weak incense to the authors, or even more so to the Entity, public or private, that bears the expense. No: here the four written introductions by Roberto Delsignore, Paolo Andrei, Marzio Dall’Acqua, and Andrea Zanlari are to be read carefully; they are the grand scene of perennial constitutive truths; of precise and surprising excavations that entrench superhistorical reasons that are as real as they come; I would even say of “obvious mysteries” that are unraveled here; and of convinced secular plots that still hold the city up as a living stronghold and as a source of universal gifts. To these necessary introductions, which stimulate the cogitative path of the entire volume, general editor Arturo Carlo Quintavalle responds symphonically by explaining what is that quid that makes Parma a “mythical place,” even in the world of contemporary communication.

With such viaticum, careful reading becomes the immersion in a garden of delights that nourishes the spirit all the more, that strengthens thoughts, that inducts culture, and that keeps the tuning fork of pleasure and enthusiasm very high. Especially since the entire volume, as we have còlected, is totally about art. And it is a triumphant art that gushes forth in the early 16th century, sustained by the culture of the entire intelligence of the city: true ideal outpouring for the creative abilities of architects and figurative masters.

The names of Correggio and Parmigianino immediately stand out, dispensers of an imaginative universe made concrete with incomparable genius: for them Parma remains an absolute gem in the cosmos of the arts. It has been written that the first of the two “came from outside,” but it is not at all a matter of foreignness since the Lords of Correggio ruled the city since the 14th century, hosting no less than Petrarch, and a branch of them was permanently present here. Antonio Allegri can be said to have been “naturaliter parmensis,” and here in fact he wanted to stay, think, act, with an identity that overturns any remoteness and refused any other invitation; his pictorial genius is a total assimilation with the temperament of the place. His anabatic protention and that kinetic induction of his compositions (which is always humorous, smiling, serene) changed the course of art history in the entire West.

Similarly it is the case with Parmigianino, a direct son of this land, who wandered for years and years but who at the beginning and end of his brief existence here left the stigma of his soul with paintings drawing on the most unsettling heights of a mystical and mysterious perfection that we cannot but say ineffable. Parmigianino’s colors, forms, and finitenesses stand above comparison: certain revelation of a soul devoted to prehuman visions.

Now, in order not to fall into a very dense series of quotations and personalities that have constipated the arts in the centuries from the seventeenth to the twentieth century, we need only point out to the reader and scholar the generational vicissitude of the sumptuous Farnese dynasty, followed by the very distinguished court of the Bourbons, and then by the refined personality of Maria Luigia, to arrive through the nineteenth-century academic revival and the diversified events of the stylistic, proto- and late twentieth-century passages, almost up to our own day. And it is a very high anthology of famous names of painters and sculptors. The caveat is the continuity of an always elevated artistic line, spread everywhere in palaces, villas, churches, incipient private collections, and then in the grandiose complex of the Pilotta Museums. A language that, even in the multiplicity of relationships, including international ones, has maintained that courtly character, Parmesan in all respects, that allows (as the volume we are honoring demonstrates) one to recognize an admirable class always, and often fascinating, of the works Parma possesses: from the sensuous myths of the Palazzo del Giardino, to the novel Greekness of sculpture; from the marvelous woods of so many furnishings to the measured intimate reflections of Amedeo Bocchi. The whole magnificent panorama is echoed by the recent superb collections of almost heraldic abstraction by Luigi Magnani and Franco Maria Ricci.

With this volume, we can say that Parma capitale-to quote Plato-possesses the interpretation of the past (anàmnesi), the intelligence of the present (diàgnosi), and the ability of the mind to order the future “according to itself” (prònoia), that is, in the field of art it can proclaim to be the holder of the κτήμα είς αεί, that is, the possession forever of full beauty.

History of Parma, 8th tome, The History of Art: 16th-20th centuries, edited by Artuto Carlo Quintavalle.

Texts by: Bruno Adorni, Andrea Bacchi, Paolo Barbaro, Daniele Benati, Cristina Casero, Enrico Colle, Marzio Dall’Acqua, Ilaria Giuliano, Carlo Mambriani, Lucia Miodini, Massimo Mussini, Tommaso Pasquali, Arturo Carlo Quintavalle, Carlo Sisi, Maddalena Spagnolo, Gian Caludio Spattini, Federica Veratelli, Simone Verde. Bibliography edited by Domenico Vera. Other authors for memory cards.

Mount University Parma Publisher, 2020.

Pages 763

|

| The cover of the escult volume on the History of Art in Parma from the 16th century to the 20th century. |

|

| View of Parma from the frescoes of the Farnese Villa in Caprarola. The Farnese presence in the Emilian city began with the episcopate of Alessandro, already a disciple of Pomponio Lieto, who brought a high depth of humanistic and religious culture here. His period saw the exciting emergence of Correggio and the beginning of Parmigianino’s career. Alexander became Pope Paul III in the fall of 1534. |

|

| Correggio. Vision of the frescoed dome of the Benedictine Basilica of San Giovanni, 1520. We see the Evangelist’s call to heaven by Jesus prodigiously descending from the empyrean, and free hovering in space over the host of Apostles, naked because holy. With this fresco, suspended in the “aetheria,” painting follows the human eye into spherical space and takes a new start in the history of European art. |

|

| Parmigianino. The face of Cupid intent on forging the bow of love. The splendid panel, executed in Parma between 1533 and 1535, is currently in Vienna. This detail is revealing of the unparalleled finesse and luminosity of Francesco’s brush, capable of taking painting to the absolute limit, yet containing a hidden mystery. |

|

| Antonio Begarelli, Madonna and Child with Saint John, albino terracotta in the church of San Giovanni Evangelista, pre-1543. The modeling genius, “touched by the taste of Correggio,” leaves in Parma some majestic and very natural masterpieces, worthy of the purest Renaissance. Their perfection and loveliness remain as a precious paradigm for Italian sculpture. |

|

|

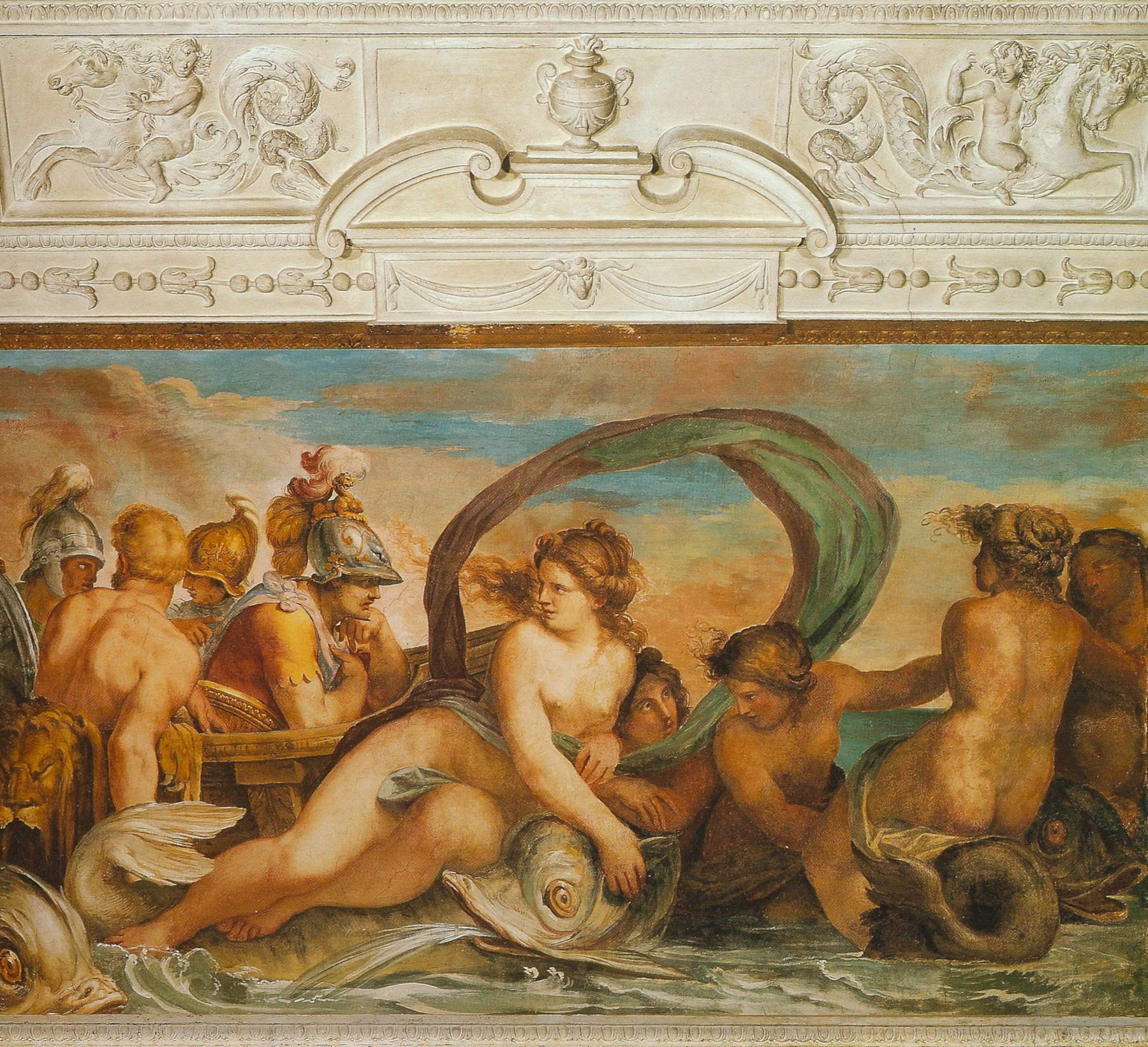

Agostino Carracci, Peleus and Thetis, fresco in the Sala d’Amore of the Palazzo del Giardino, 1600-1602.

Agostino’s arrival marks the Carracci’s overwhelming interest in the Parma art site, and with the frescoes in the “Reggia di là dall’acqua” he gives the start to the new century that will see here in the Farnese Duchy the presence and work of Annibale, Aretusi, Soens, Schedoni, all with relevant works, andppoi of Lanfranco and Badalocchio up to Lionello Spada and Bernabei. The necklace of great secentists will be enriched with other names and, together with Stringa, it will be the sublime Carlo Cignani who will close the century, still in the Palazzo del Giardino. |

|

|

Leonardo Reti, the Chapel of the Madonna of Constantinople in the church of San Vitale in Parma, 166-1669. Leonardo, part of a dynasty of skilled plasterers of Lombard origin, left this resounding masterpiece in the city where his guild operated extensively with a figurative and compositional skill worthy of the most admirable Baroque. |

|

|

Ducal Palace of Colorno. The ingenuity and hands of Ferdinando Bibbiena and Giuliano Mozzani during the 18th century shaped this complex that may well represent the life and rich artistic taste of Parma in the Age of Enlightenment. It is the court of Philip, Elizabeth, and Ferdinand of Bourbon that celebrates the elegance, furnishings, gardens, and graceful architecture later desinent in crisp neoclassicism. Gaetano Callani, sculptor and painter, worked beautifully in the period. |

|

|

Left: Francesco Baratta the Younger, Chastity, 1728 marble. Church of Santa Maria della Steccata. Right: Gaetano Callani, Saint John the Evangelist, 1765 stucco. Church of Santa Maria dell’Annunziata. The two solemn statuesque specimens both vigorously display an evident possession of strength and elegance in the heart of 18th-century Parma. In the volume they stand within a myriad of images of high beauty that accompany this century and the entire second part of the treatise. |

|

|

Francesco Scaramuzza (1803-1886). Silvia and Aminta, 1829. National Gallery of Parma. The large painting is highly significant of the moment of transition between neoclassicism and the Romantic movement, and it also bears witness to the remarkable level of the Academy of Fine Arts, protected by Maria Luigia and nourished by literature, of which he later became Director. In the first half of the nineteenth century, among many valuable authors, the personality of Paolo Toschi, especially engraver, stands out, creating the typical climate of neo-correctivism. |

|

|

Ballroom of the Glauco Lombardi Museum Foundation. The museum, due to the donor’s tenacious collections, is of twentieth-century composition and enjoys a recent arrangement. Here contemporary Parma celebrates itself in the figure and memory of Duchess Maria Luigia of Habsburg. It is a historical reunion much loved by the citizens. |

|

|

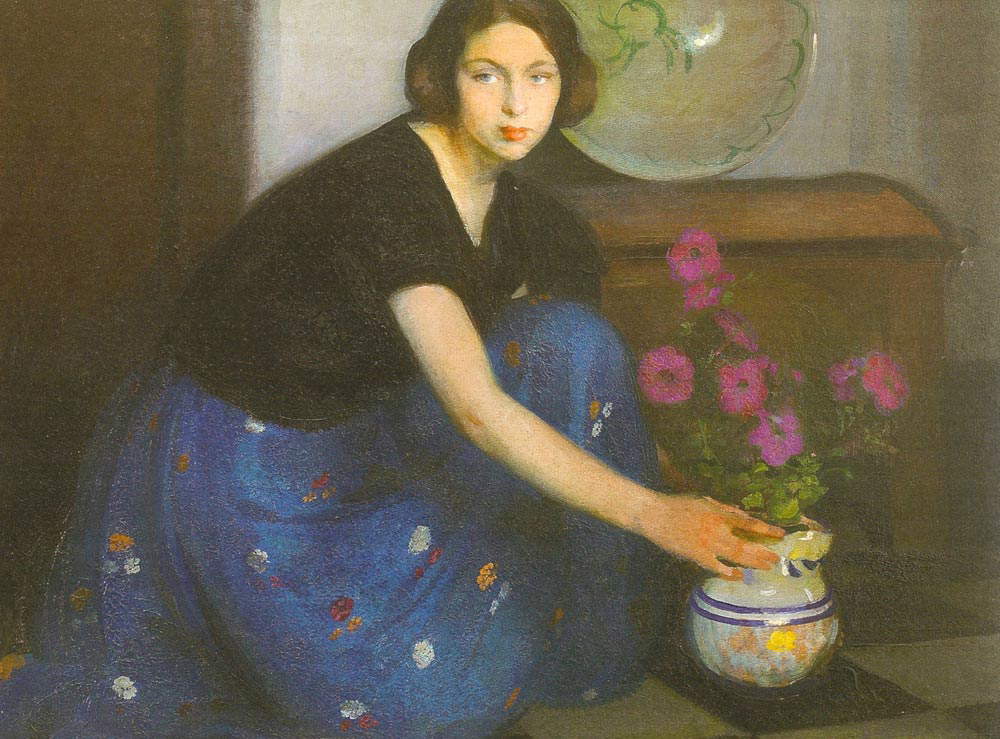

Amedeo Bocchi. Bianca with a vase of flowers, 1925. Monteparma Foundation.In Bocchi’s leavened and dense painting, the young woman seems to await that choral recognition of beauty and sweetness that is due to her beloved city. |

|

|

The Pilotta and Piazzale della Pace taken from above, according to Mario Botta’s design. In this image we want to condense the ongoing Museale reorganization but also the signaling of the living artistic creativity of the twentieth century and the new millennium. |

The author of this article: Giuseppe Adani

Membro dell’Accademia Clementina, monografista del Correggio.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.