Those who wish to make a curious visit to the great Palace of Revere, there where the last Duke of Mantua of the Gonzaga line was born, might see the model with which the ancient game of crossing ferries on the Po, with people and goods, using the very energy of the river, is demonstrated. A trick surely implanted by those true workers in the things of the world who were the Benedictine monks of St. Benedict in Polirone, so close and so obedient to structuring the territory according to the careful delivery of their rule, “Ora, Lege et Labora.”

This brings us to the year of our Lord 1007, when Tedald of the Attonids (955-1012), taking over from his father Adalbert Atto as a great feudal lord in the imperial system, joined the transalpine ways of the noble families and wanted to have a pertinent monastery for himself and his lineage, with the formula that was later called the “family closter.” For this he transformed an ancient chapel near the Po, and above all he entrusted the ineunte cenobio to the Benedictine Order (1007). It would be later that his descendant Boniface would accentuate the fame of the revered hermit Simeon,

The riverside settlement corresponded in fullness to the founder’s expectations by concentrating a good number of monks who through a centuries-long presence regimented the course of the great river and the Lirone tributary, who spread the network of reclamation over the uncultivated fields, and who drew many benefits from the agricultural vastness brought to good use. The monastery already took shape, from the beginning, as an organism with diverse activities, all coordinated to the spiritual life, applications of knowledge, and social development of the population that pertained to the area. Hence a series of activities on product transformations, the expansion of architecture, sacred and receptive, and especially on bibliographic collections that ranged from every possible kind of science to biblical, theological, and moral treatises.

The long life of the abbey and its growing importance, from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance and well beyond, has obviously attracted the interest and publications of various historians, thus forming a bibliography as interesting as it is very often intricate and difficult, made more arduous by excavations that are always partial and uncoordinated, but also abandoned by the documents, given the relentless dispersion of archives and collections that recent centuries especially have had to record. A bibliography which we do not cite here by titles but which remains stimulating and rich inductions for many in-depth studies. And it is the monumental structure of the Cenobio, with its various articulations, that still attracts the inquiring eye of researchers and pointers. If, moreover, historical events require their own specific hermeneutic methodology, the physical realities that still exist today present more concrete fields of decryption and exegesis that refer back to past events, but link them to spaces and functions of more direct mirroring, not infrequently themselves speaking.

We thus find of great help the recent publication by Professor Paolo Piva, former chair at the University of Milan, who chooses the field of art to lead us into the most attractive events of the great sacred complex. It is the volume L’Arte nella Abbazia di Polirone. A Historical Profile (2024), which points out with extreme accuracy all the architectural-constructive, and then furnishing and directly pictorial-plastic events that have enriched over the centuries this monastery which was - not by chance - a pole of wisdom and an unavoidable stage in the cultural geography of Europe. All the more useful is this publication as it leads us through the various dispossessions and resolves the fate of many works. In this work the author also performs a valuable task of clarification and on the roles that various artists probably sustained at stages that do not always appear originally documented. A summarily useful overview-supported by Carlo Perini’s beautiful photographs-guides serenely through the present presences and puts to rest many past hesitations.

The drafting of the work (226 pages) includes the revisiting of the first two chapters of an earlier edition, and then the great secular arc of the arts that were applied by the monks and that become protagonists for the next four chapters. While the noble Tedald, son of Atto Adalbert, must be regarded as the founder, certain pre-existences can still be documented and link to the long late antique moment as evidence of a geographical location with precipitous tasks. Thus the first two chapters, supported as the whole volume is by constant graphic and photographic demonstrations of real preciousness, lead us from a remote chapel of St. Simeon to the first conformation of a proper complex that included the choral church, the first cloister, and the venerated Oratory of St. Mary, all linked by the orderly liturgical unfolding of monastic processions. These two chapters-very interesting-accompany us to the end of the Middle Ages and collect such profoundly interesting elements as floor mosaics, some of which can still be admired on present-day visits, and a series of paintings now dispersed. Remarkable in every sense is the Crucifix, recently attributed to Michael of Florence (second quarter of the 15th century), which must have been placed in the wall of the jubé toward the lay church area.

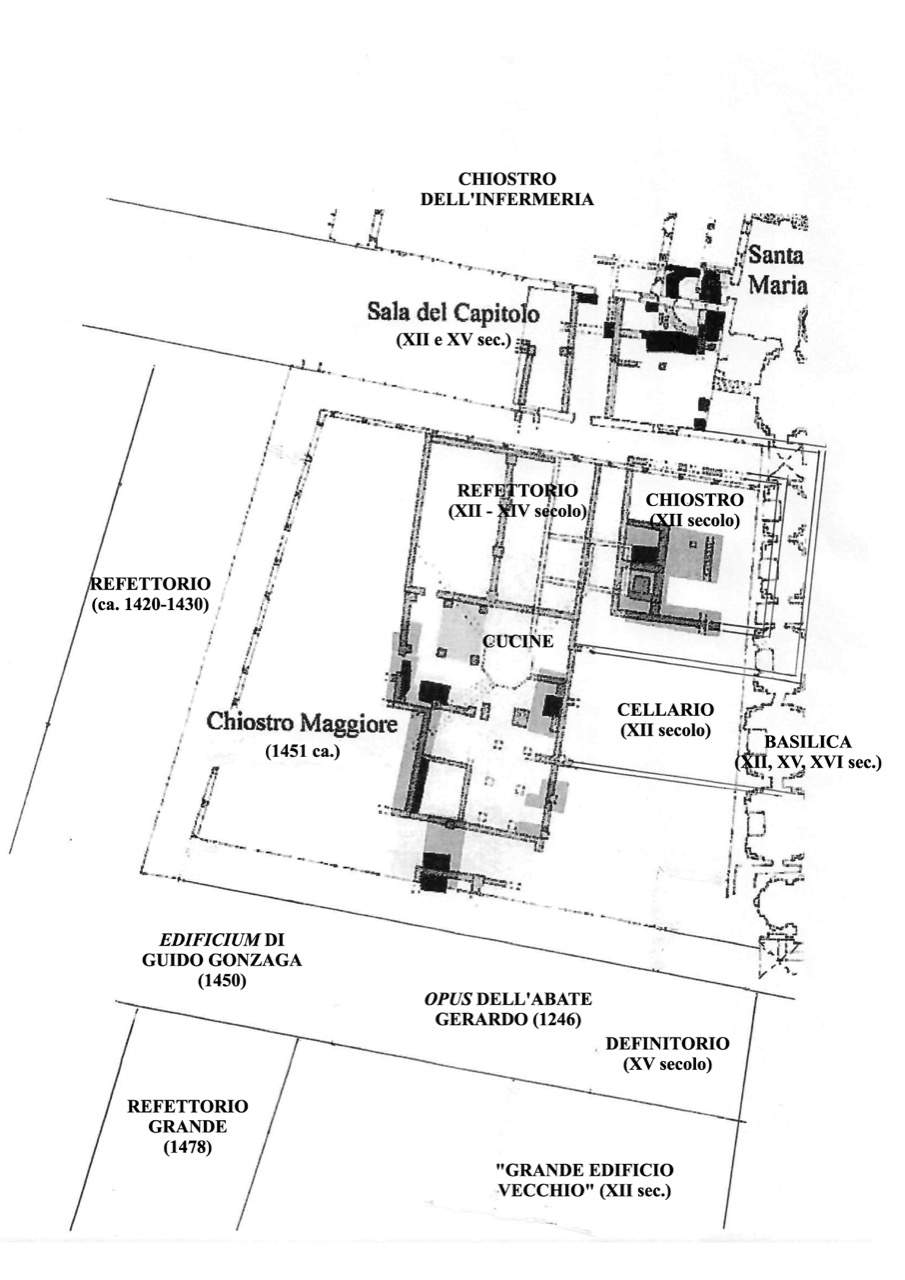

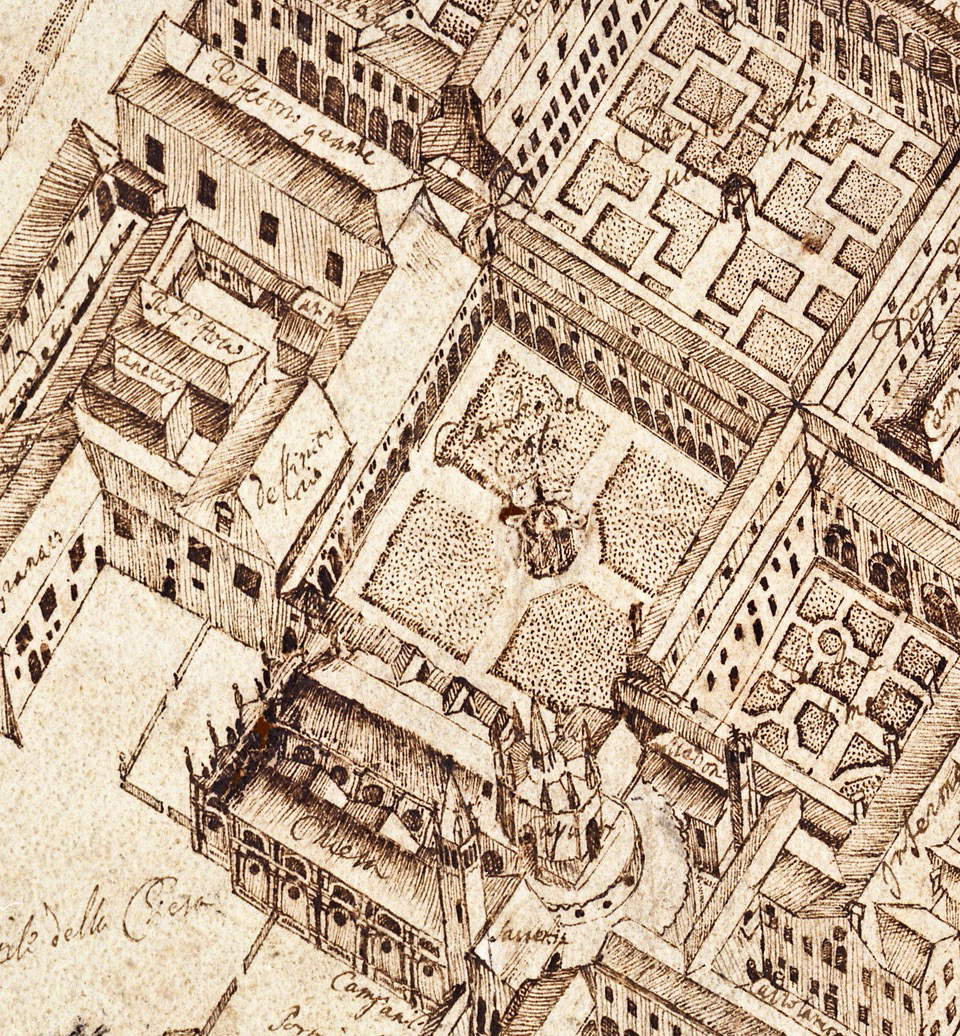

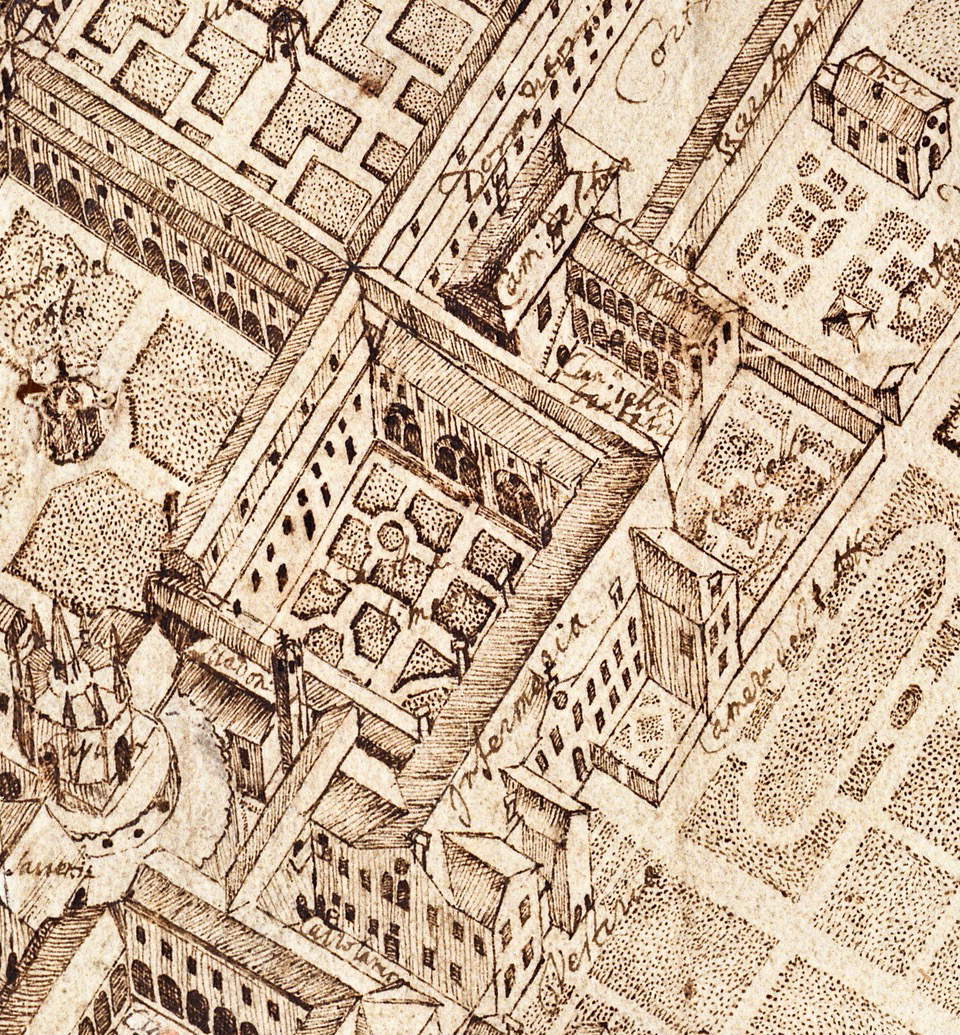

The third chapter is devoted to the “long building site of the fifteenth century and its developments.” Here, too, the author reviews and clarifies many previous studies, and examines the great and articulated renovation that centered on the realization of the main cloister, after extensive works, and that saw as a continuous propeller the noble Guido Gonzaga who was first commendatory abbot, and then-after the coenoby’s adhesion to the Cassinese Congregation-a great supporter of the works of enlargement and modernization of the built complex. In fact, the new library, the monks’ infirmary, the “definitory” towards the basilica were arranged, and above all the large crusader dormitory was created on the upper floor. Also attributed to 1478 is the refectory, a large structure measuring 47 by 11.70 meters (height 11.35 meters), while all the covered connections on the first floor were welded together. The reading of these notable cycles of masonry interventions is weighed against every datum in plan and elevations still existing today. The discussion then moves on to consider the start of the multifaceted group built to the southeast of the Basilica, intended for outsiders, with which indeed “the fifteenth-century monumental complex of the coenoby corresponds to a gigantic building effort that occupied the monks for almost the entire century.”

The fourth chapter, very large and very important, covers the entire sixteenth century starting from the Abbey’s adherence to the Cassinese Congregation and the presence of the exceptional personality of Gregory Cortese - the youthful friend of Pope Leo X - who weaved among the northern monasteries an entirely new vitality of works, of environments pregnant with meaning, and of artistic trophies. Here Paolo Piva’s lengthy study becomes truly indispensable for the very many connections he proposes and illustrates. A first pictorial question is that of the interaction between the older Girolamo Bonsignori and the young Correggio: if the organ door with the transport of the Holy Ark is now recognized to Correggio, the assignment of the fresco of the Refectory remains too debated. The author reviews every opinion and every step, rightly insisting on the too largely imperfect state of the mural painting where, for example, the architectures are executed in fresco and the other parts in drywall, and reminds us that any in-depth judgment can only be made by one who has climbed the restoration scaffolding. It follows that Correggio had a large part of the work, fully holding up to the Roman influences of the trip in 1513, and pointing to this Polyronian endeavor as an indispensable stage of the ineunte and brilliant Allegri, all bent on creating a spatial breadth--biblical and theological--that would later always accompany him.

The chapter continues with the vast examination of Giulio Romano’s work and his glorifying transfiguration of the monastic basilica, guided by the exceptional mind of Gregory Cortese, a true theologian - later cardinal - and almost masterful guide of an authentic Abbey lived in toto for prayer and meditation. Here indeed Professor Piva’s rhythmic accompaniment reveals the complexity of the Juliesque work both with regard to the Romanesque-Gothic load-bearing structures, unbearable but stupendously recalled to a new breath, and to the choral conformation of the entire ecclesiastical space and what we might call its centripetal force that summoned all the arts to illustrate the choir-head, choir, aisles, chapels and tornacoro, thus making become the beautiful basilica the explicit projection itself of the “civitas coelestis.” A very high exception even within the Benedictine Order, where a certainly Roman breath pervades this structural and spatial undertaking, filling it with wonder and light. In the great semantic-figurative anthology, the author investigates and demonstrates the choices - always highly qualified - of the architectural score, of the ornamental details, of the special handicraft orders (see the superb adventure of the wooden choir), and of the dense competition of the pictorial altarpieces and wall paintings. In this last field, one ideally recovers the presences in their real time of authentic masterpieces such as the works of Paolo Veronese, Anselmo Guazzi, Lattanzio Gàmbara, Mazzola-Bedoli and others. It is crowned by the magnificent presence of Antonio Begarelli’s statuary necklace all around the middle of the 16th century, which still graces the pronaos and the great Basilica. but a truly organic effort that unites all the liturgical apparatus is that of the Sacristy, which still thrills the visitor. The entire treatment of the chapter illuminates each affair and arranges a series of “merit” connections that touches on masters, subjects and dates in a historical arrangement that thus becomes the necessary framework for current cultural knowledge of the monastery.

Chapter Five turns to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a period in which, for historical reasons, artistic inclinations are toned down but which-curiously enough-prepares for the drafting of what the author calls “the formation of a myth.”

In the first glimpse of this period, in fact, Matilda’s memory reappears in what we might call the second tomb, while the body remained in the small church of Santa Maria, ideally awaiting the Roman call of Pope Urban VIII Barberini (1630). Here the author turns his and our attention to the unvisitable Sacristy Chapel, where Baroque echoes propose a series of truly attractive solutions, and where the still visible bronze Crucifix was kept, an admirable work that Marco Scansani has convincingly likened to Alessandro Algardi.

But the abbots’ architectural commitments in the second half of the 17th century centered on the transformation of the guest quarters and the drafting of the related monumental staircase. We are in the monastic area southeast of the Basilica, and this becomes the solemn part, where the sumptuous ascent to the piano nobile is gratified by the stuccoes of the very famous Giovanni Battista Barberini, an international artist of uninterrupted creativity who left decorations of “great plastic strength and tenderness” at the Polirone from 1674 onward. In fact, the staircase gathers a very vast and complex culture that is almost memorable and serves as an ideal pivot for the entire renovation of the Chiostro dei Secolari and the two new apartments arranged under the careful supervision of the Gonzagas. The late seventeenth century and the following century record the stone statue of Matilda, tall on the outside; the facade of the Chiesa Maggiore as now seen, a dense application of ornamental craftsmanship, and the pictorial sequence of canvases of the Veronese school where Giambettino Cignaroli excelled. But the 18th century was also one of confusing artistic and cultural initiatives, which do not escape the author’s precise attention.

The short and final Chapter Six is significantly titled “Epilogue. Dilapidation of a Cultural Legacy” and lists too many interventions of false restoration, removal, and even havoc that unfortunately thicken in the twentieth century. Where the most dramatic damage was that inflicted in 1985 on the Correggio fresco, ruined in more ways than one, while altering the cloister gardens and disfiguring the elevations of the main cloister. But finally, by way of refreshment, today several restorations still in progress appear decidedly appreciable.

Professor Piva’s publication therefore becomes a necessary and reliable mirror of the vicissitudes of an incomparable monumental complex, and nobly invokes every attention and care for the continued existence of this august workshop of faith and art on the bank of the great river.

The author of this article: Giuseppe Adani

Membro dell’Accademia Clementina, monografista del Correggio.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.