How globally recognized isItalian contemporary art? That’s what a report by the BBS Lombard company presented last April 21 and titled How well (re)known abroad is Italian contemporary art? a 229-page pdf document that includes interviews with curators and museum directors (from Cecilia Alemani, curator of the international exhibition at the 2022 Biennale, to Milovan Farronato who curated the 2019 Italian Pavilion, from Eike Schmidt director of the Uffizi to Ilaria Bonacossa, director of the future National Digital Museum) and a second part of data analysis.

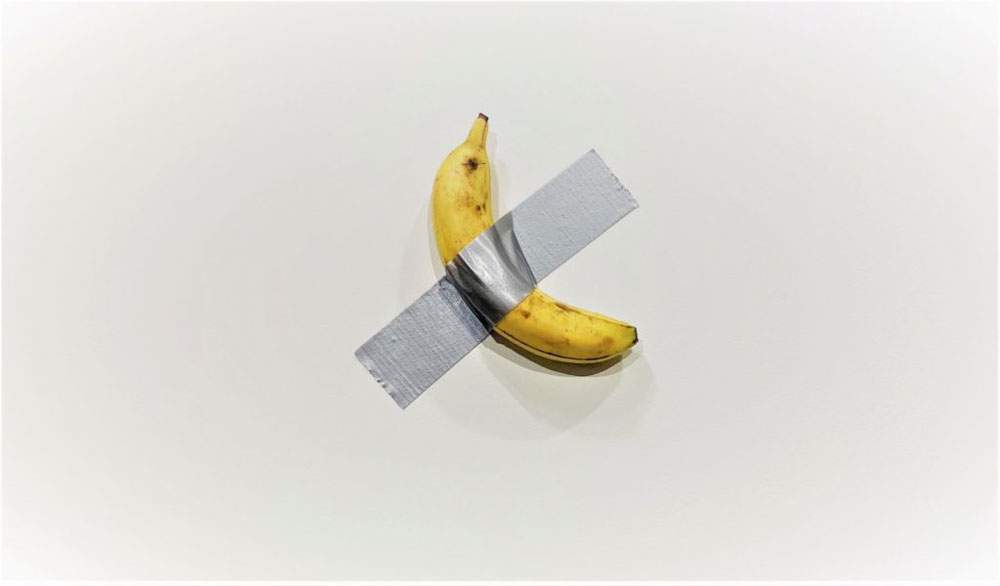

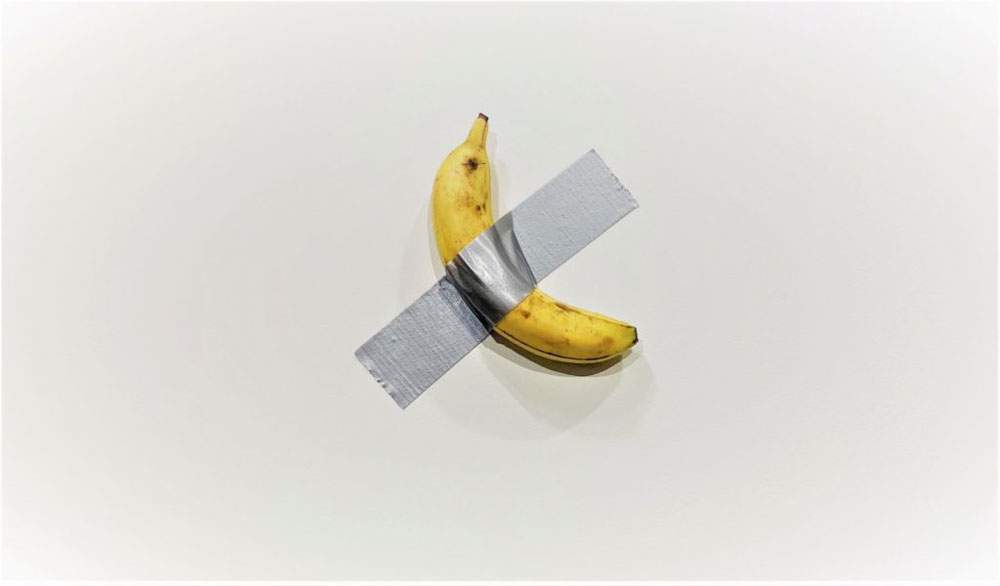

Directors and curators were asked who are the most visible living Italian contemporary artists abroad, which ones have not yet achieved adequate visibility, and what are the main shortcomings of the Italian system. The most famous names are more or less always the same: from the Arte Povera artists who are still active(Giuseppe Penone, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Gilberto Zorio) to the most cited name ever, that of Maurizio Cattelan, to younger artists such as Rudolf Stingel (perhaps the second most famous after Cattelan, excluding the Poveristi), Roberto Cuoghi, Rosa Barba, Francesco Vezzoli, Vanessa Beecroft, Lara Favaretto, and Monica Bonvicini. Wider, however, are the splits on the names “to be enhanced.” As for critical issues, “one of the main causes of the lack of valorization of Italian artists with a consequent flaw in our country’s contemporary art system,” the report explains, summarizing the result of the interviews, “is the inability to create networks at the global level, first and foremost between Italian academies, Italian contemporary art museums and foreign counterparts. There are still too few Italian museums capable of positioning themselves as a point of reference for the international scene, due to the frequent absence of stable multi-year programming with definite resources. Thus monographic exhibitions or exhibitions of works by mid-career artists produced by our museums with foreign institutional partners capable of conveying Italian production abroad are still too rare. It is easier and less risky to make cash by favoring well-known artists and crowd pleasing exhibitions, often already packaged and based on import-export, thus giving up the basic function of forming the Italian public’s taste on contemporary art. In general, there is a lack of an integrated and effective strategy for the institutional promotion of contemporary art abroad and a synergy between Italian and foreign institutions. This is true both for the Italian Cultural Institutes that present a rich activity of valorization, but with little organicity and concertation, and for Italian galleries that struggle to network with foreign colleagues and take the risk of Italian mid career artists.” Other problems include little space for art in schools, little market support, and fiscal constraints that burden Italian galleries.

The data analysis to try to understand how much Italian art is recognized abroad starts by considering the collections of 76 museums in 23 countries, identified as the world’s major contemporary art museums, to look for works by Italian artists after 1960. The most featured artists are Cattelan (13 collections), Beecroft (7), Rosa Barba (6), Luisa Lambra and Tatiana Trouvé (5), Monica Bonvicini and Enrico David (3), and Diego Perrone and Francesco Vezzoli (2). Also in the same institutions, artists’ solo exhibitions were counted: 12 for Cattelan, 10 for Vezzoli, 9 for Trouvé, 8 for Rosa Barba, 7 for David, 3 for Bonvicini. As for the presence in the group shows, the most present is still Cattelan (58) followed by Beecroft (28), Bonvicini (27), Trouvé (26), Barba (20), Vezzoli (16), Paola Pivi (13), Giuseppe Gabellone and Enrico David (12), Cuoghi (11), Patrick Tuttofuoco, Luisa Lambri and Diego Perrone (10), Lara Favaretto and Superstudio (9). Few artists with at least one solo exhibition abroad in the last five years are Rosa Barba, Yuri Ancarani, Enrico David, Marie Cool and Fabio Balducci, Formafantasma, Chiara Camoni, Maurizio Cattelan, Serena Ferrario and Lorenza Longhi.

The report also calculates Italy’s presence at the Venice Biennale, which, the report explains, “represents in the art system one of the most important stages in an artist’s career and an opportunity for great visibility in front of an international audience,” and recalling that Italy has won the Golden Lion for best participation only once, in 1999, for the project of Monica Bonvicini, Bruna Esposito, Luisa Lambri, Paola Pivi and Grazia Toderi. The analysis considered the Biennale’s editions since 2007 (a date from which Italy has collected little: the Leone alla Carriera in 2013 to Marisa Merz, and special mentions to Roberto Cuoghi in 2013 and 2009). The number of Italian presences has been low, the report reconstructs: in 2007 with Robert Storr between the Giardini and the Arsenale only six Italian artists out of 100 (6 percent), ten out of 87 (11.5 percent) in the 2009 edition curated by Daniel Birnbaum, and 10 out of a total of 84 (11.9 percent) in the 2011 edition curated by Bice Curiger. While in the 2013 Exposition curated by Massimiliano Gioni there were 14 Italians out of 164 (8.5 percent), down to four out of 139 (2.9 percent) in the 2015 exhibition curated by Okwui Enwezor, and five out of 193 (2.6 percent) in the 2017 one curated by Christine Macel. Even fewer in 2019, two out of 84 (2.4%), in the exhibition curated by Ralph Rugoff.

The analysis also covers the world’s second most important exhibition after the Biennale, namely Documenta in Kassel, and other major international Biennales, such as those in Istanbul, Liverpool, Lyon, Berlin, São Paulo, Sydney, Shanghai, Singapore, Gwangju, and then again Manifesta, Müster’s Skulptur Projekte, Belgrade’s October Salon and others. There is also room for a look at the Italian artists most in the media: the most visible artists of the last year were Gian Maria Tosatti, Davide Quayola, Edoardo Tresoldi, Fabio Viale and Marinella Senatore. The BBS Lombard report also ranks the 50 Italian artists in history most mentioned by the media in the last 10 years, according to elaborations by Articker: the podium is occupied by Leonardo da Vinci, Caravaggio and Michelangelo, followed in 4th and 5th place by Amedeo Modigliani and Sandro Botticelli. Surprisingly in sixth place comes Maurizio Cattelan, who even overtakes Raphael, Lucio Fontana and Titian. Artemisia Gentileschi closes the top 10. The other living artists on the list are Pistoletto (11th), Penone (22nd), Vezzoli (23rd), Francesco Clemente (26th), Stingel (35th), Pivi (36th), Senatore (38th), Bonvicini (40th), Enzo Cucchi (47th), and Flavio Favelli (48th). The latter ranks just ahead of Donatello, 49th in the rankings.

Again, taken into consideration the presence of Italians in international galleries and the presence of Italian galleries abroad and foreign galleries in Italy, as well as auction results (among the top ten Italian artists by turnover between 1999 and 2021 there is only one living artist: Lucio Fontana ranks first, followed by Piero Manzoni, Alberto Burri, Alighiero Boetti, Giorgio Morandi, Marino Marini, Enrico Castellani, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Giorgio De Chirico and Fausto Melotti). Mercilessly comparing the 2021 turnover of living Italians to foreign artists: our best-selling artist, Cattelan (turnover of $1,223,805, followed by Matteo Pugliese with $331,016 and Francesco Vezzoli with 179.389), comes in behind France’s Claire Tabouret, Invader, Julie Curtiss and Richard Orlinski, Germany’s Daniel Richter, Neo Rauch, Sterling Ruby, Katharina Grosse, Wolfgang Tillmans and André Butzer (and the comparison for analysis is limited to France and Germany only).

In short, how well is Italian art recognized abroad? “The analysis of the functioning of the support system for contemporary art production in our country,” the BBS Lombard report explains in its conclusions, “provides us with some information. We do not believe that the research done is exhaustive, but some reflections are possible: the fortune at the museum and market level of Italian art of the 50s-60s-70s (Fontana, Burri, Arte Povera) clearly emerges against the light. But for artists born after 1960, what is the establishment of their works in the main institutional and commercial venues of international contemporary art in the last 10-20 years? Responses to interviews with the 24 curators reveal a handful of names of Italians on whom international attention is focused. Maurizio Cattelan dominates, followed by Francesco Vezzoli, Monica Bonvicini, Enrico David, Paola Pivi, Tatiana Trouvé, Roberto Cuoghi, Rosa Barba, and a few others. Beyond the quality of the work, which we give as inescapable, what in the unanimous opinion of those interviewed gives the artist visibility is the experience of studying and working abroad, which allows for the creation of a network of international relationships with curators, galleries and museums. For curators, one of the reasons why Italian artists have not yet been fully valorized is the absence of an integrated and effective strategy of Italian institutions for the promotion of contemporary art abroad and of a synergy between Italian and foreign institutions. Funding for the production of works is also found to be insufficient and not continuous, as is the educational offer of the academies. However, the map of international museums where contemporary Italian art has been exhibited reveals that it is not invisible, on the contrary: in 76 foreign museums surveyed, it is present in 61 permanent collections, including 51 by the artists under study. The most featured works - according to the Artfacts.net database - are by Maurizio Cattelan, Rosa Barba, Vanessa Beecroft, Luisa Lambri and Tatiana Trouvé, Monica Bonvicini, Enrico David, Diego Perrone and Francesco Vezzoli. There is also a change of pace in the Venice Biennale: if the presence of Italians in the International Exhibitions of the editions from 2007 until 2019 is very rarefied, from this year with curator Cecilia Alemani, Italian artists represent 12 percent of the total against 5 percent in the previous Biennales (2007-2019). In fact, knowing the Italian and international scene well certainly helps to enhance the local scene. The Italian Pavilion, which for years has favored the collective formula, which is less easy to communicate or not very functional for in-depth artistic projects, this year for the first time assigned space to a single artist, Gian Maria Tosatti.”

Finally, it should be noted that “while Christie’s and Sotheby’s Italian Sales in London over the past 20 years have strengthened the international market for artists of the 50s-60s-70s, the circulation of contemporary Italians on the secondary auction market is rarefied: it is far lower in total annual sales when compared with French and German colleagues. Wondeur’s artificial intelligence helped analyze the role of cities in the art system: Milan is more at the forefront of the Italian art ecosystem with a significantly higher success rate than Rome and Venice, although its propensity for risk does not differ from that of the other two cities. This may be attributable to the fact that Italian cities prefer already established and well-known artists. Milan, despite having a market positioning aligned with the higher ones of Paris, Berlin, and Los Angeles, is still distant from these cities in terms of its museum system and cultural centers, as it fits into a fragmented national context. It is therefore imperative for a city like Milan, which aspires to become competitive on contemporary, to attract funding and develop a strategic vision. Also in Arte Generali’s analysis elaborated with the support of Wondeur, the absence of a proven network pushes Italian artists to perfect their path abroad, between Europe and the United States, consolidating relationships with foreign institutions. In addition, economic policies to support the pandemic crisis have failed to give oxygen to the contemporary, lacking legal recognition of the artistic profession and related professions. Fiscal initiatives should be undertaken with the aim of endowing the system with greater transparency and, at the same time, making the transfer of works more fluid.”

|

| But do they know contemporary Italian art abroad? Here's what a report says |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.