by Redazione , published on 06/09/2020

Categories:

Contemporary art

/ Disclaimer

Moataz Nasr, an Egyptian artist born in 1961, uses his art to address the problems of today's Egypt and the contemporary world.

Painter, sculptor, multimedia artist, photographer. Egyptian Moataz Nasr (Alexandria, 1961), a self-taught artist, came to art late, since his first activities date back to 1995: until then, Nasr had worked in the field of economics (in fact, he graduated in this discipline from the University of Alexandria), and that year he decided to try his hand at an art competition organized by his country’s Ministry of Culture, obtaining third place. Internationally, however, it was a major Italian gallery, the Galleria Continua in San Gimignano, that launched him, in the early 2000s: thus came the first major exhibitions (his works were shown in group shows at the Centre Pompidou, the Hayward Gallery, the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo, the Sharjah Museum, and the Archaeological Park of Pompeii) and major events, above all the apotheosis of 2017, when Nasr represented his country at the Venice Biennale.

With his work, Nasr, who hardly loses sight of his Egyptian roots, brings together different languages to explore the contradictions of globalization, the connections between his country’s past and present and beyond, those between East and West (and in particular between the Arab world, where he comes from, and the Europe that has given so much to his career), the ways in which the choices of politics and economics impact people, but there is also room for the individual’s states of mind (beginning with a sense of powerlessness in the face of the great changes the world knows today). Nasr thus becomes an almost disenchanted but still elegant observer of what is happening in the world today. Starting in Africa and then going all over the world. Underlying this work are the very movements of human beings. “Since the beginning of time,” says the artist, “the idea of immigration to this world has been a constant search for life. Human beings are constantly moving. From north to south, from south to north, the purpose of this endless and restless circular movement is always the same: sustenance, survival, the search for a better life.”

As early as 2005, a year in which Nasr had already made some important experiences (he had, for example, exhibited at the São Paulo Biennial), Egyptian curator Liliane Karnouk, in a book on the history of Egyptian art of the 20th and 21st centuries, described him as “an innovative and versatile artist, a self-taught artist who admits to one exception, that of having learned informally from his conversations with Mona Hatoum,” and as “an artist who works with a great sensitivity towards the material, with a clarity of vision that allows him to express original ideas with simple means.” In one of his earliest works, 2003’s Echo (perhaps the first work to have a major international resonance), a 4-minute, 27-second video projection, Nasr presented a recording from the 1960s and a contemporaneous one to demonstrate, through a number of statements from which Egyptians’ frustration with the country’s socio-economic problems emerged, how Egypt’s political and social situation had not changed in decades.

On the same tenor was a series from the following year, Man Made, which dealt with the theme of human beings’ inability to relate freely and healthily to power (in the photographs, images of a horse wearing blinkers and a man harnessed in the same way as the animal were placed in opposition). Five years later, in 2011, the same themes are declined in a different way through another of Nasr’s seminal works, The Maze (The People Want the Fall of the Regime): an installation drawn with strips of grass that make up the slogan that gives the work its title (“The People Want the Fall of the Regime”: these were the convulsive days of the Arab Spring) in kufic script, the script that in parts of the Arab world was used to decorate the palaces of power. Consequently, in an operation of detournement, one of the tools of the powerful becomes a means by which the artist expresses a will of those in power who are subservient to it. A feeling of estrangement heightened by the fact that this cry of protest appears as a refined and well-tended garden.

|

| Moataz Nasr, Echo (2003; 4 min. 27 sec. video) |

|

| Moataz Nar, Man Made (Hamada) (2006; c-print on Dibond, 100 x 150 cm). Ph. Credit Ela Bialkowska. Courtesy the artist and Galleria Galleria Continua |

|

| Moataz Nasr, The Maze (The People Want the Fall of the Regime) (2011; installation view at Jardin des Tuileries, Paris). Ph. Credit Oak Taylor-Smith. Courtesy the artist and Galleria Galleria Continua |

|

| Moataz Nasr, The Tower of Love (2011; 7 towers, including 2 of ceramic 175 x 49 x 49 cm and 172 x 38 x 38 cm, 1 of iron 192 x 28 x 28 cm, 1 of bronze 190 x 35 x 35 cm, 2 of crystal 173 x 33 x 33 cm and 212 x 41 x 41 cm, and 1 of wood 155 x 89 x 69 cm). Ph. Credit Ela Bialkowska. Courtesy the artist and Galleria Galleria Continua |

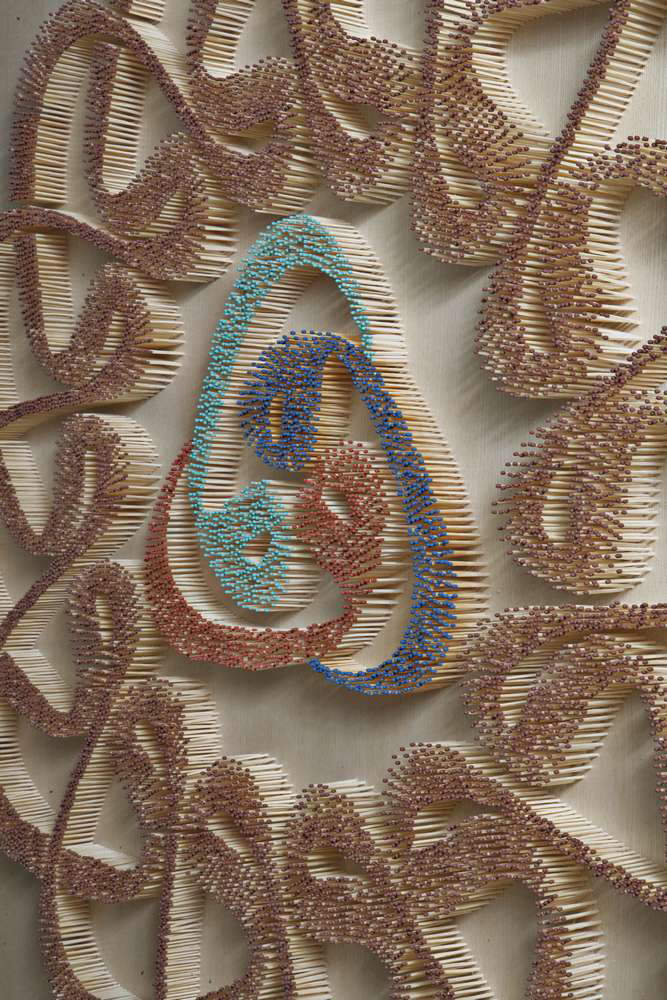

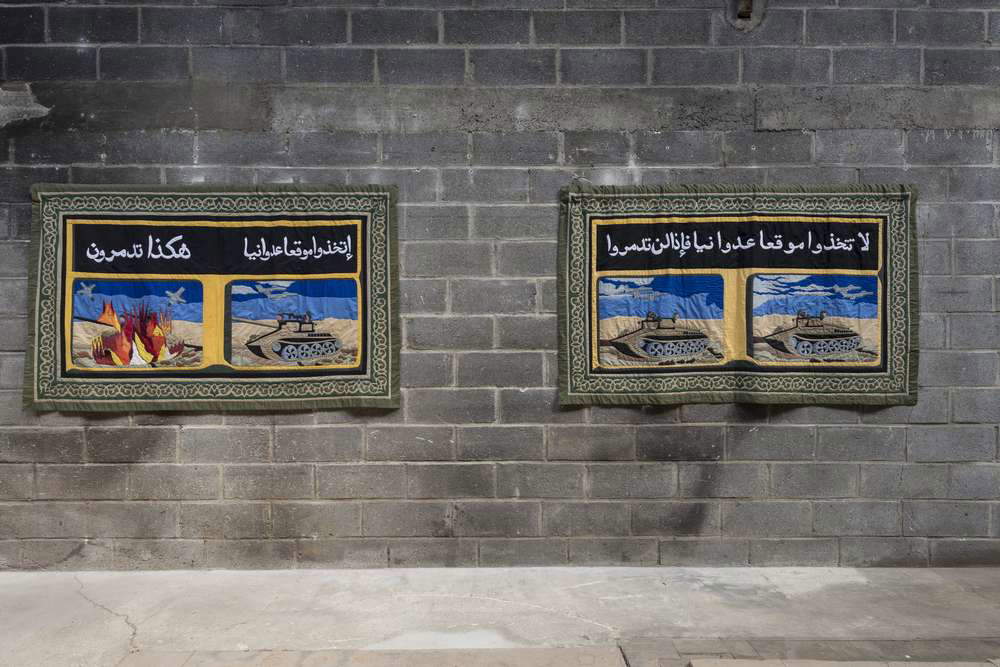

Also from 2011 is another of his most famous works, The Tower of Love, where a series of towers combining architecture typical of different civilizations and especially different religions (Christian, Islamic, Jewish, Buddhist, Hindu) are united under a single flag, that of love, whose name is placed on the top of each tower. Artistic elements from the past and from tradition, and in particular from the Islamic tradition, are often present in Nasr’s art (this was seen with The Maze and Towers of Love), and yet they are employed to address issues of urgent topicality: it is in this sense that works such as Khayameya (2012) or Infinity (2011), for example, are born, textiles that propose motifs typical of the textile art of Egypt, drawn, however, with matches, signifying that themotionless political situation of the country can flare up at any moment, or such as Propaganda (2008), textiles that depict moments of heated conflict in the Iraq War.

For his participation in the 2017 Venice Biennale, at the Egypt Pavilion, Nasr brought to the lagoon his work The Mountain, a 12-minute film shot in an Egyptian village: it tells the story of Zein, a girl who leaves the village, which is located at the foot of a mountain (hence the work’s name), emigrates, studies and obtains an education, and then returns to challenge the local authorities. A work that thus investigates several themes, including generational conflict (which, in Egypt, also means conflict between the desire for renewal and entrenched power), emancipation, the desire for freedom, and the courage that destroys fear, and in particular the fear of change (Moataz Nasr has often stated that The Mountain is a work centered precisely on the feeling of fear: “the mountain,” he said, “is fear, fear understood in a general sense, fear of everything, fear of the unknown, fear of authority, fear of talking to someone you don’t know-all the different kinds of fear that grow in our lives. I decided that this time we would face the mountain and conquer it.”).

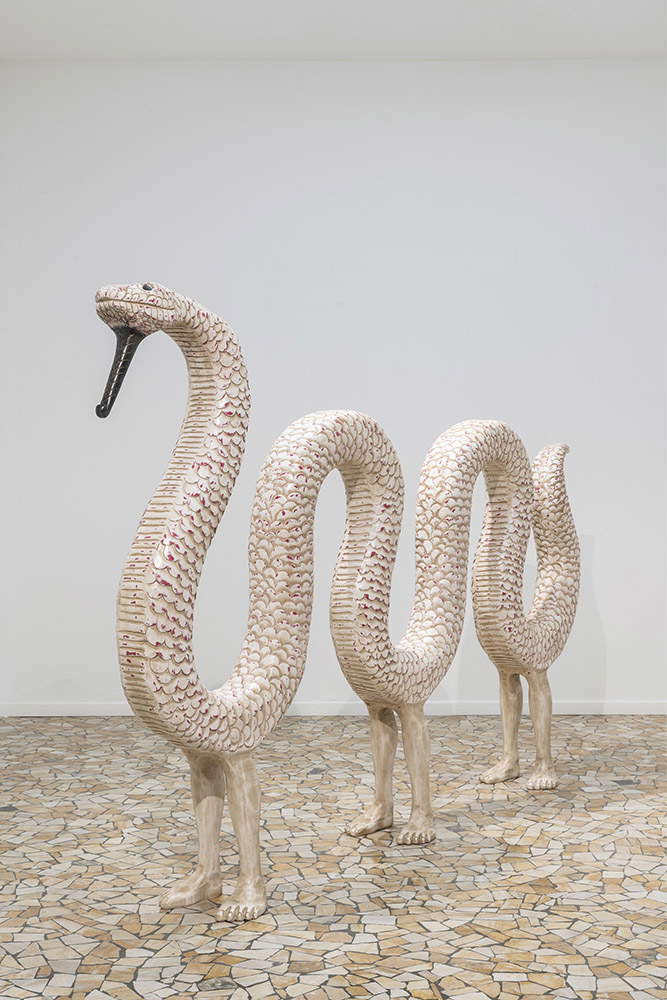

Moataz Nasr’s most recent project is the solo show Paradise Lost (a direct quotation from John Milton’s poem), curated by Simon Njami in the spaces of Galleria Continua, a sort of small anthology in which Nasr exhibited works he has already presented, beginning with The Mountain, to new works that offer further overviews of the current world, foremost among them the condition of women, a theme on which one of the Egyptian artist’s strongest series, The Slave Market, is centered (of the kind that even Orientalist artists of the late nineteenth and up to the early twentieth century depicted in their works: Nasr himself was inspired by the paintings of Jean-Léon Gérôme), thrown, however, in the face of the viewer with contemporary characters, or as the moment of conflict we are living through, embodied in the figure of Apophis, the character in Egyptian mythology who symbolizes evil, or again as the need to find a safe place that finds its expression with the hut in The Shelter, which gives an impression of fragility, showing that security is not a solid value.

A kind of summary and summation of Nasr’s universe, as Njami explained. “The apocalyptic description of the world made by Milton after his expulsion from the Garden of Eden,” the curator wrote, “is suggestive. It is so because it represents a fairly faithful metaphor for our world, prior to or without any divine intervention. And this world we owe solely to ourselves, to our actions. To what we have done and what we have omitted to do. Moataz Nasr’s exhibition could be seen as a space situated at a crossroads between hope (Heaven) and disillusionment (Hell). Its elements create a strange resonance with a fictitious scenario. It is a stage, a scenario in which the structure of the old cinema that is the gallery gives a hallucinatory or hallucinated presence. What was in this garden that we heard so much about? A mountain, a river, trees, fruits, animals, a snake and humanity, represented by man and woman. We find again the mountain, the woman, the snake. The main tree in the movie theater could act as a tree; the structure occupying the entrance as a prism, as a secret passage to a world unknown to human beings.” A project that, in Njami’s words, represents “a journey of initiation,” “an eerie immersion in a space that mixes myth and reality.” The most recurring elements of Nasr’s art.

|

| Moataz Nasr, Khayameya (2012; matches on wood, Plexiglas, 200 x 200 x 10 cm). Ph. Credit Oak Taylor-Smith. Courtesy the artist and Galleria Galleria Continua |

|

| Moataz Nasr, Infinity (2011; 15,500 matches on wood, Plexiglas, 160 x 160 x 7 cm). Ph. Credit Ela Bialkowska. Courtesy the artist and Galleria Galleria Continua |

|

| Moataz Nasr, Propaganda (Don’t take an attack position or you will be destroyed) and Propaganda (Take an attack position and that’s how you will be destroyed!!) (2008; fabric diptych, 125 x 208 each). Ph. Credit Oak Taylor-Smith. Courtesy the artist and Galleria Galleria Continua |

|

| Moataz Nasr, The Mountain (2017; video installation, 12 minutes). Ph. Credit Ela Bialkowska. Courtesy the artist and Galleria Galleria Continua |

|

| Moataz Nasr, The Mountain (2017; video installation, 12 minutes). Ph. Credit Ela Bialkowska. Courtesy the artist and Galleria Galleria Continua |

|

| Moataz Nasr, Om El Saad (The Slave Market) (2019; c-print on Dibond, 150 x 210 cm). Ph. Credit Ela Bialkowska. Courtesy the artist and Galleria Galleria Continua |

|

| Moataz Nasr, Rose (The Slave Market) (2016; c-print on Dibond, 185 x 146.5 cm). Ph. Credit Ela Bialkowska. Courtesy the artist and Galleria Galleria Continua |

|

| Moataz Nasr, Shelter (2019; wood). Ph. Credit Ela Bialkowska. Courtesy the artist and Galleria Galleria Continua |

|

| Moataz Nasr, Apophis (2019; wood). Ph. Credit Ela Bialkowska. Courtesy the artist and Galleria Galleria Continua |

|

| The torments of today's Egypt in the art of Moataz Nasr |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.