Museums reopen, and silent Exhibitions can rise from the dormancy of cloistered time. The National Gallery of Bologna reopens, and here a fervid review, in itself very rich in multiple motives, can rattle for dignity and conclamation in the well-understood, and how profoundly, panorama of that national event that is called the “sign of Raphael.” A “sign” that certainly flickered in the mind and on the hands of Alfonso Lombardi (Ferrara, 1497 - Bologna, 1537), a fervent contemporary of the Urbino, rich in formal effervescence in the art of sculpture and openly capturing the admirable proposals of the “perfection of the Renaissance.”

A sign today grasped with acute and conscious afference by Marcello Calogero and Alessandra Giannotti, and arranged in a multiple Exhibition where the Bolognese crucible (a geographic heart, a real area of multivalent exchange of the recycling of the arts) really knew splendors perhaps transient but of the highest interest and still capable of critical seductions that here are stretched out in a brief but flashing overview of comparisons.

It will not be in vain to recall in brief what we can call the sculptural stratification in Bologna from the Middle Ages to the early sixteenth century. The presences of works and masterpieces due to Manno Bandini da Siena, Bettino da Bologna, the other authors of the Arche, Nicola Pisano, Fra’ Guglielmo and Arnolfo di Cambio, Niccolò dell’Arca, Jacopo della Quercia, up to Michelangelo in his two stops, and Donato di Gaio di Cernobbio at the Madonna di Galliera. In this Bologna is truly an urban anthology of plastic art containing high poles of expression, capable then of being continued throughout the entire sixteenth century and subsequent centuries.

An extroverted and tumultuous personality with a sure sculptural vocation, Alfonso Lombardi can also be guessed from a quick and illuminating biographical glimpse. He was born in Ferrara to a “Cittadella” Lucchese moved here to serve the Este court, and here he imbibed an architectural, sculptural, fittile and pictorial culture of the highest caliber: he worked for the court on ancient marbles and created two fountains, in bronze and marble (one “amenissima”) for the island of Belvedere to feign joyous natural “wonders.” He admired the magical painting of Dosso Dossi and was able to study Raphael’s cartoons that came to the Duke in 1517. In 1519 he went to Bologna much flattered by the competition for theHercules to be placed in the Sala degli Anziani in the Palazzo Pubblico, and won it. The power of this figure still amazes. Here he begins to change his own surname from “Cittadella” to “Lombardi,” that is, he takes on his mother’s surname. The resounding success puts him in immediate prominence in the city of Bologna, and as early as 1519 (still a minor, with his father’s consent) he begins the extraordinary figurative set design of the Funeral of the Virgin for the Confraternity of Santa Maria della Vita: an entire theater with large terracotta figures, decidedly Raphaelesque in inspiration. Other commissions rained down, intersecting thickly with other sculptors, such as Zaccaria Zacchi and many painters: among them the colorists of the fictile sculptures and the layout artists of the fresco backdrops. Bologna, as a “papal city,” truly became a fervid workshop of the arts that involved everything and where painters of all stature found in Raphael’s legacy the leaven for conversions and enterprises in many places. Alfonso Lombardi seems to be at the center of a continuous agitation of commissions and building sites: this is masterfully acknowledged in the Catalogue. The presence of Francia had already waned, and little influence was given to the disordered energy of Aspertini, who nevertheless gave himself to marble in the lunette of the right portal in San Petronio; silently, meanwhile, Correggio’s sublime Noli me tangere had arrived at Casa Hercolani, from which perhaps Lombardi took inspiration for the composed and classical marble Resurrection in the lunette of the left portal in San Petronio; but the game of expressive adaptation was played between Dosso, Garofalo, Girolamo da Cotignola, the sharp Innocenzo da Imola, and if anything with the enchanting Girolamo da Treviso, of whom the exhibition offers an extremely admirable Holy Family.

|

| Alfonso Lombardi, Hercules and the Hydra (1519-1520; large terracotta figure; Bologna, Palazzo d’Accursio; Sala degli Anziani) Executed to universal acclaim for the visit of Pope Leo X. |

|

| Alfonso Lombardi, The Funeral of the Virgin (1519-1521; terracotta statuary group; Bologna, Oratory of Santa Maria della Vita) Awell-known work, it takes up in various figures the gestures of the protagonists in Raphael’s School of Athens. |

|

| Alfonso Lombardi, Resurrection, The two central marble figures in the lunette of the left portal of San Petronio (Bologna), 1526 The sculptor had previously given several panels for the rich portal. With these he directly confronts monumental statuary. The solemn firmness of the almost naked Christ is reminiscent of Correggio’s Risorto, which had recently arrived in Bologna. The calm astonishment of the Roman soldier is singular. |

|

| Dosso Dossi, Apparition of the Virgin and Child to Saints John the Baptist and the Evangelist (1517; oil on panel, transferred to canvas, 153 x 114 cm; Florence, Uffizi, Depots) Painted for Cardinal Ippolito d’Este and originally placed in San Martino in Codigoro.Itshows a spatial and gestural scheme indebted to Raphael’s cartoons just arrived in Ferrara. |

|

| Girolamo da Treviso, Holy Family (1530-1535; oil on panel, 72 x 60 cm; Cento, Grimaldi-Fava Collection) Painter who from before this exquisite composition had ideally offered Lombardi that suave and lofty “dialogue on classicity” of which the impetuous sculptor happily took note. |

|

| Girolamo da Treviso, Holy Family, detail A close view that allows us to understand the admirable absorption of the classical language of this rare master, in his Bolognese period, as Daniele Benati points out, after Longhi. A painter who stands at the center of the Bolognese “crucible” of the advancing sixteenth century. |

The stylistic repertoire of fittile sculpture in Bologna in the 1920s was balanced between the quivering and tragic legacy of Guido Mazzoni and the echoing sweetness of Antonio Begarelli, but the real new direction marked by Lombardi was directed toward a volumetric and gestural realism all of its own (the Santi del voltone, the Madonna of Faenza, the grandiose Lamentation over the Dead Christ in San Pietro in the city) and if anything on the dialogue of pictorial monumentality that found precisely in Girolamo da Treviso the interlocutor with highly and intensely musical responses. Towards the end of the decade the commissions became even more numerous, especially from the Fabbrica di San Petronio: and our Alfonso juggled between requesting a house from the Fabbrica itself, and supplying models to be executed in marble by other sculptors. He was by this time master of a workshop-business from which also came the monumental relief decoration, in stucco, for the main chapel of Santa Maria del Baraccano and a number of very high-priced funerary monuments.

But political events had a profound effect on Lombardi’s own life, on his highest ambitions, on the trials to which he boldly aspired, sustained by that lightning-fast genius of modeling skills that made him prestigious and capable of astonishing everyone. Et venerunt Reges! Spanish dominance was asserting itself hard in Italy, after the bloody battle of Pavia (1525) and after the tremendous sack of Rome (1527), so that the young Charles of Habsburg obtained the crown of King of Italy and the crown of the Holy Roman Empire in Bologna, through the hands of Pope Clement VII, in February 1530. Already in September 1529 Federico Gonzaga had arrived in Bologna, who asked Lombardi for a series of marble portraits for the Palazzo del Te (a preparation for the imperial visit), but above all the now famous sculptor obtained the commission for the large ephemeral apparatuses necessary for the coronation: a task carried out with extraordinary skill and effectiveness in a very short time. This put Lombardi in the very forefront among the princes gathered for the historic event, and generated the Vasarian anecdote of Vecellio introducing Lombardi almost covertly to the sessions for the portrait of CharlesV, where the sculptor admirably modeled the emperor’s image in small scale and obtained the commission for a magnificent marble bust.

Anecdotes aside, Nostro’s career soared to a European level, in demand by Italian and Spanish nobles especially for honorary portraits where he excelled. He was invited to Spain, but went to France where he met the king. He traveled and worked. In 1533 he accepted an invitation to join the court of Cardinal Ippolito de’ Medici and went to Rome. There he portrayed Pope Clement VII, met Michelangelo, and worked on the funerary monuments of other pontiffs. But in 1535, when Cardinal Ippolito died, Lombardi moved to Florence, and then back to Bologna. He worked again for San Petronio and the Duke of Mantua, but his earthly existence ended abruptly on December 1, 1537.

A lively artist, he was at the center of that astral revolution that involved Italian art because of the “Raphael phenomenon”: he worked for Dukes, Cardinals, Sovereigns and Pontiffs, holding high the Italic quality of figurative language. He was a dialectical artist who can still engage us in the extremities of his sculpture: the emphatic power, the statuesque and classical structure, the sorrowful pathos, and the ecstatic dwelling on some touching softness.

|

| Alfonso Lombardi, Madonna and Child (1524; terracotta; Faenza, Pinacoteca Comunale) The sculptor had previously given several panels for the rich portal. With these he directly confronts monumental statuary. The solemn firmness of the almost naked Christ is reminiscent of Correggio’s Risorto, recently arrived in Bologna. The calm astonishment of the Roman soldier is singular. |

|

| Girolamo da Cotignola, Holy Family with St. John (1520-1523; oil on panel, 62 x 50 cm; Forlì, Pinacoteca Civica, Piancastelli Collection) The domestic and splendid panel testifies to the full Raphaelesque conversion of the strong Romagna author, who arrived in Bologna in the fullness of his means. A conversion tempered by the clear spatial and communicative overhang. Valuable for this are the studies of Raffaella Zama. |

|

| Alfonso Lombardi, Bust depicting the Savior (1522-1524; polychrome and gilded terracotta, 104 x 77 cm; Florence, Private Collection) Solemn larger-than-life effigy, prominently saved from a larger figure, whose powerful colloquiality and gestural emphasis we must appreciate. Lombardi’s true masterpiece renders us his invigorating concentration of sculpture-painting: an all-Po Valley Renaissance apax. |

|

|

Alfonso Lombardi, Saint John the Evangelist under the Cross (1525-1532; polychrome and gilded terracotta, height 200 cm; Castel Bolognese, Church of San Petronio) This magnificent standing tuttotondo is paired with the similar figure of the grieving Virgin Mary: both in significant juxtaposition with a central Crucifix. Absolute proof of the art of oratory. |

|

|

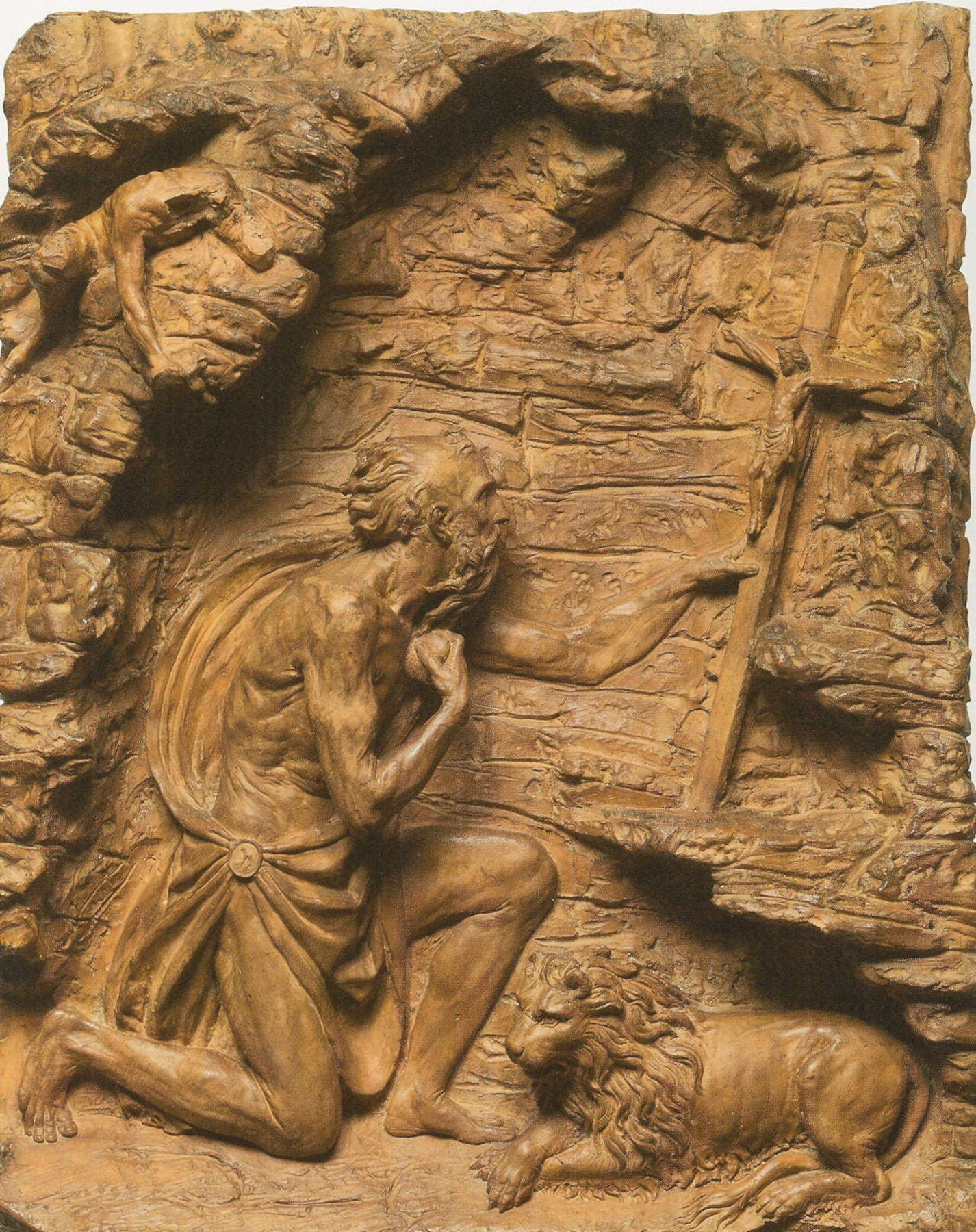

Alfonso Lombardi, Saint Jerome at Prayer (1524-1530; terracotta, 56 x 46 x 11.5 cm; Faenza, Pinacoteca Comunale) The piece, intended for private devotion, was originally patinated in bronze as evidence of a well-known patronage nobility. Here it gives us an impression of Lombardi’s freshness in the relief. |

|

|

Alfonso Lombardi, Bust of Alfonso I d’Este, detail (1530; marble, 69 x 59 x 26 cm; Modena, Galleria Estense) The bust was one of the first delivered to Federico Gonzaga, after his request in 1529.Thegrandeur and perfection of execution, on marble personally chosen in Carrara, testify to Lombardi’s skill even in slower processes and on difficult material. |

The author of this article: Giuseppe Adani

Membro dell’Accademia Clementina, monografista del Correggio.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.