One of the first contributions we come across while scrolling through the catalog of the exhibition Antonello da Messina, on view at the Palazzo Reale in Milan until next June 2, is a paper by Roberto Alajmo, who, as is well known, is a writer and playwright by trade, but for this occasion has decided to take on the role of iconologist to venture into an analysis of the iconography ofEcce Homo in the production of Antonello da Messina (Messina, c. 1430 - 1479). Already the fact of finding, in the catalog of an exhibition of fifteenth-century art, a text written by someone who by profession deals with books and theaters and not with ancient paintings, could lead most people to express some initial signs of disappointment. But let us give the benefit of the doubt: the curator of the Milanese review, Giovanni Carlo Federico Villa, in the introduction (written together with Caterina Cardona, who together with Villa edited the catalog), informs us that the account of the works of the Sicilian painter who was composed, for the occasion, by no less than five different writers, including the aforementioned Alajmo, responds to a specific request of his. The desire, he says, was to “construct a book that would also make use of eyes other than those of art historians.” Legitimate thought: in the history of literature there are several instances of writers (among them very high names, whom we should perhaps not bother) who have given us enlightening, pregnant and extraordinary readings on works of the past. Admittedly, these are not very many, but they are enough to set a precedent. With one certainty, however: in almost all cases, these were writings that, taking the Newtonian method at face value, operated by synthesis rather than analysis.

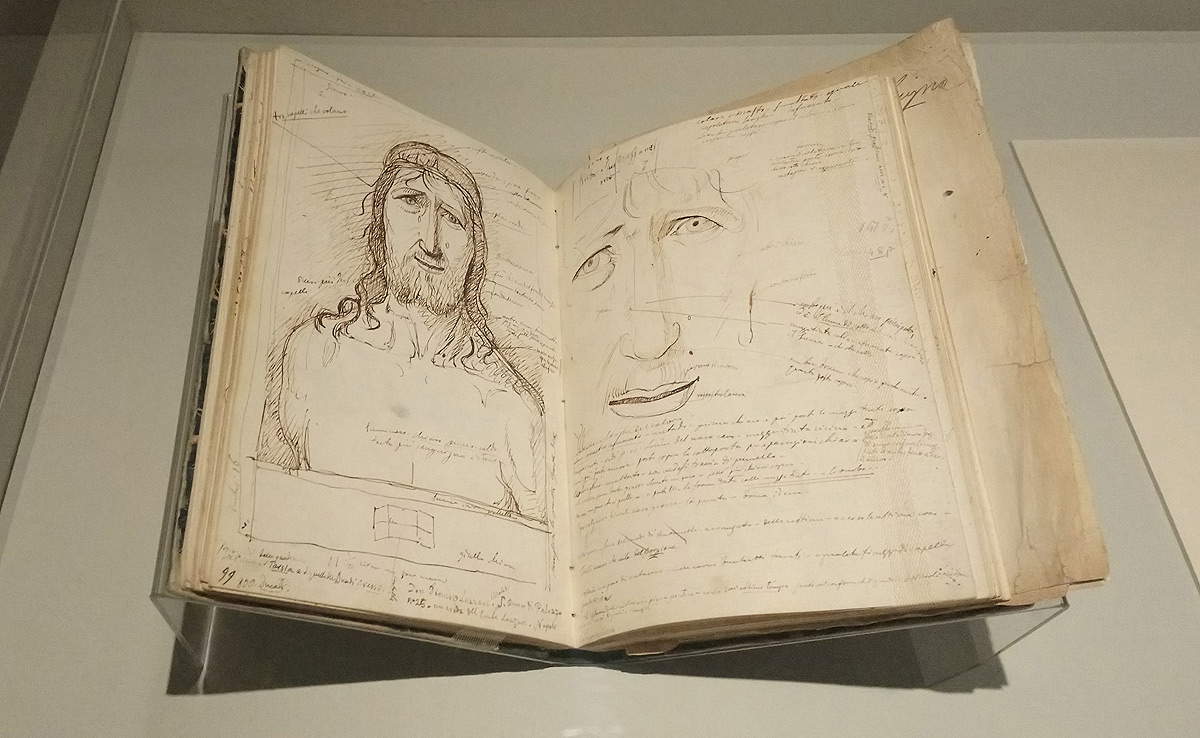

However, this is not the case with Alajmo: his short paper seeks to probe the expressions of Antonello’s Cristi in order to understand on the basis of what assumptions the Messina artist “was obsessed with the face of Christ, and in particular with the defeated and suffering Christ.” Each of these Christs “is sorrowful in its own way,” Alajmo asserts, and this characteristic must necessarily entail a reason, which according to ours lies in Jesus’ “doubt” on the part of Jesus “that he was laboring in vain for his entire existence, and with greater suffering in his last hours, those of torture and ludibrium.” In other words, Alajmo is sure of the fact that, for Antonello, Christ was neither God nor man, “but a Sisyphean creature, who tried in vain to mediate between God and men, coming out devastated from the undertaking, punished perhaps by the very God on whose behalf he had attempted mediation.” A thought that, if manifested at the time, would have sent Antonello directly before an inquisitor: and it is idle to point out that there is no suitable element to support such a hypothesis. But for Alajmo these are details: indeed, he goes so far as to suggest that “even the rope, which in almost all the variants Christ wears around his neck, seems to want to symbolize the inevitability of this destiny, the constraint that obliges after every disillusionment to pull ahead, to start over even knowing that starting over will not help.” The reckless exegete is not even touched by the idea that the origins of the superb invention of the rope around Jesus’ neck are, if anything, to be traced to the religious literature of the time (there is a passage in the Meditationes of the pseudo-Bonaventure in which the devotee is invited to look at Christ and the “lasso around his neck in the manner of a thief”), and it certainly makes sense to think that Antonello was in contact with Franciscan patrons who may have provided some cues (given that the Meditationes are a Franciscan-inspired text), rather than deeming him some kind of heretic without the slightest foothold, but only by observing the expressions of his Christs. Finally, as if that were not enough, Alajmo ends his contribution by venturing (the term is his own) a sequence aimed at distorting “factual chronology” (what exactly “factual” referring to a chronology means is unknown), but “rather follows a logical psychological evolution.” And this logical psychological evolution leads him to move last the Christ in Pieta in the Regional Museum of Messina, the one painted on the verso of the Madonna with the Blessing Child and a Franciscan in adoration, unanimously considered a youthful work (and, moreover, not even the physical presence of a Franciscan friar in a panel cited by Alajmo himself would seem to have made him change his mind about the painter’s inner drives).

Those who have not yet set foot in the Palazzo Reale might think that Alajmo’s intervention represents an exception, punctually belied by the exhibition itinerary: on the contrary, it has been decided to open this piece with the improbable lucubrations of the Palermitan playwright precisely to anticipate that any low expectations that the reader of the catalog might have after such a discouraging debut are actually confirmed in the exhibition. Antonello da Messina is a glaring example of how a distinguished scholar such as Giovanni Carlo Federico Villa, a nucleus of masterpieces that is difficult to assemble, a pounding publicity battage, and an exhibition venue that is among the most active and avant-garde on the national scene are not sufficient ingredients to package a good and worthwhile exhibition. For sure, most of the public will find it a “beautiful exhibition,” in the sense that it is commonly understood: that is, an exhibition filled with wonderful works (after all, there is almost all the best of Antonello’s production, even if we are far from the numbers of the great exhibition at the Scuderie del Quirinale in 2006, which to this day still remains the most important and complete review ever held on the Sicilian painter). And that it is therefore a “beautiful exhibition” is a given: however, just as one gives the possibility that a film acted by great actors may be boring or unsuccessful, in the same way it is not masterpieces that make an exhibition interesting, useful and original. If an exhibition exposes to the public parades of masterpieces but there are shortcomings in the scientific project (which we could compare to the screenplay of a film) and in the choice of the works, as well as in their arrangement in the itinerary (the direction, to continue with the cinematic simile), the result can only be negative.

|

| Audience at the Antonello da Messina exhibition in Milan, Palazzo Reale |

|

| Audience at the Antonello da Messina exhibition in Milan, Palazzo Reale |

|

| Audience at the Antonello da Messina exhibition in Milan, Palazzo Reale |

Since the last Antonello exhibitions (the one already mentioned at the Scuderie del Quirinale, and then we could mention, for size, the one held at the MART in Rovereto between 2013 and 2014) there have been no significant scientific innovations on his work, or at least not such as to have to justify a new monographic exhibition only five years after the last one: it is worth remembering thatscientific usefulness should be the first reason behind an exhibition, as Francis Haskell taught. But even if one wants to be less restrictive, one could positively evaluate an exhibition even without any major novelty, on the basis of its popularizing value: however, the enormous defect of Antonello da Messina is that in the itinerary, with the exception of Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle ’s notebooks, which will be better discussed later, one finds exclusively works by Antonello, and the context has been totally left out. The reconstruction of the historical, economic, cultural and social environment in which the artist worked, and which is unquestionably fundamental to understanding Antonello’s painting, is entrusted to a few panels placed mostly at the beginning of the itinerary: but, excluding the Madonna by Jacobello d’Antonio (Antonello’s son), placed at the conclusion of the exhibition, there are no works by other artists, and the same is true for the catalog (next to Antonello’s works are only those by nineteenth-century artists who retraced his legend). This inexcusable absence makes impossible an operation of contextualization that is indispensable, especially in an exhibition intended for such a wide audience: conversely, the great exhibition at the Scuderie del Quirinale, curated by Villa himself together with Mauro Lucco, a specialist on Antonello, included many works suitable for weaving the threads of the cultural milieu of Messina, Naples and Venice in the second half of the 15th century, the cities where the painter was formed and worked.

The result, therefore, is an exhibition with a distinctly hagiographic and mythographic flavor, and the caption panels themselves do not help dispel this aura (the first is titled “The Myth of Antonello” and begins thus, "For centuries Antonio de Antonio, Antonellus messaneus in autography, has been a myth"). The feeling of visiting an exhibition that has more to do with mythography than with anything else increases when one discovers that many rooms have been set up to contain a single work, and this happens from the very beginning of the exhibition: the first room, for some strange reason, is all dedicated to St. Jerome in the Study of the National Gallery in London, a painting that is placed towards the end of the author’s career, and which was placed at the opening probably to introduce the art of Antonello da Messina. Or at least this is the function attributed to it in the apparatuses that accompany the visitor on the tour: and yet it is not clear why precisely the St. Jerome, not least because, moreover, it is very difficult to summarize (or introduce) the entire art of the Messina artist with a single work. The hagiography prepared in the halls of the Royal Palace reaches its climax when one reaches the room that houses theAnnunciation arriving from the Regional Gallery of Palazzo Abatellis in Palermo, presented to visitors as “the perfect icon,” as “an absolute masterpiece in the history of art,” as “capable of soliciting emotions and feelings in every viewer.” an emphasis that obliterates the work of those who spend their time to remind us that works of art are not fetishes but are, to paraphrase Roberto Longhi, figurative texts that are always related to other objects. And obviously, even in the case of the room of theAnnunciata, the context has been totally zeroed out: there is no precise reconstruction that explains to the public that theAnnunciata is obviously due to Antonello’s genius, but it is not a sudden flash of lightning, but rather an image that reworks suggestions that the artist drew from his studies, and which he arrived at by degrees. No mention is made, for example, of the other Annunciation, the one in Munich, for which a later date than the one in Palermo is proposed in the catalog, but without any explanation of the reasons why (that is, it is postponed by three to four years with respect to the 1473-1474 date proposed by a large part of the critics and accepted by the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, the museum that preserves the panel). And yet, even willing to present the work as an “icon,” the exhibition does not avoid blaspheming it, since it is placed behind a reflective and dirty glass (and the same fate has befallen other Antonello masterpieces, such as the Cefalù Portrait of a Man, with the embarrassing result that it becomes impossible to fully enjoy works with this problem).

But there are additional elements that make the sloppiness of the arrangements stand out. From time to time one encounters blow-ups with reproductions of some details of the paintings, but often the quality of the photographs is so low (the photos appear grainy and taken at a resolution totally unsuitable for reproduction on a larger scale) as to make their presence unnecessary. And again, there are sections devoted to some important paintings by Antonello, but the paintings are absent: a large panel, placed at the entrance of a corridor, announces a section number 9 dedicated to the San Cassiano Altarpiece, but crossing the threshold one discovers that in fact the extraordinary work that Antonello made during his stay in Venice has remained quietly in its home, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, and visitors, after the panel describing the altarpiece, are immediately catapulted into the room dedicated to the Trivulzio Portrait and the Portrait of a Man in the Galleria Borghese. The very arrangement of the rooms in some passages adopts impractical solutions: for example, the Portrait of a Young Man from the Philadelphia Museum of Art has been placed in such a cramped environment that it suddenly throttles the flow of visitors (as one can imagine, the Palazzo Reale exhibition is taken by storm), with the resulting discomfort. All this is without taking into account that the entire construction of the exhibition appears to be very unorganic: a chronological criterion was basically followed, but with frequent and incomprehensible digressions.

|

| Antonello da Messina, Annunciation (c. 1476; oil on panel, 45 x 34.5 cm; Palermo, Palazzo Abatellis, Regional Gallery) |

|

| Antonello da Messina, Portrait of a Young Man (1474; oil on panel, 32.1 x 27.1 cm; Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art) |

|

| Antonello da Messina, Portrait of a Man known as Ritratto Trivulzio (1476; oil on panel, 37.4 x 29.5 cm; Turin, Museo Civico di Palazzo Madama) |

|

| Antonello da Messina, Portrait of a Man (c. 1475; tempera and oil on panel, 31 x 25.2 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

|

| Antonello da Messina, Saint Jerome in the Study (c. 1474-1475; oil on panel, 45.7 x 36.2 cm; London, National Gallery) |

|

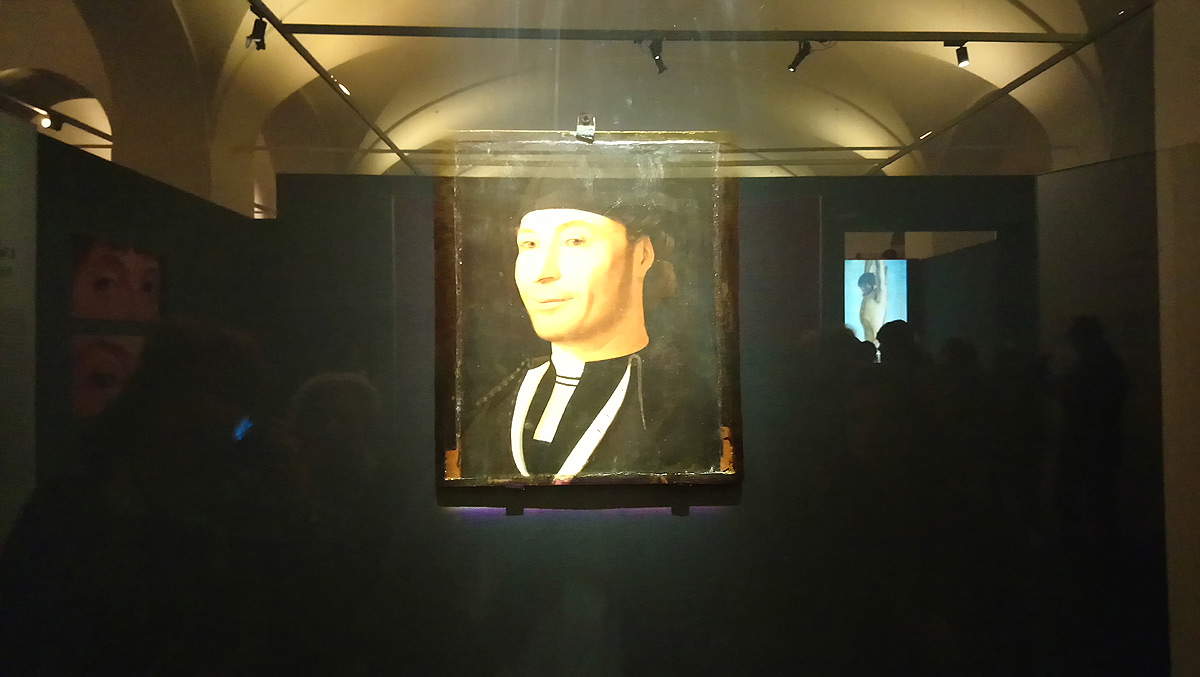

| Cefalù’s portrait at the Palazzo Reale exhibition |

|

| TheAnnunciation at the Royal Palace exhibition |

|

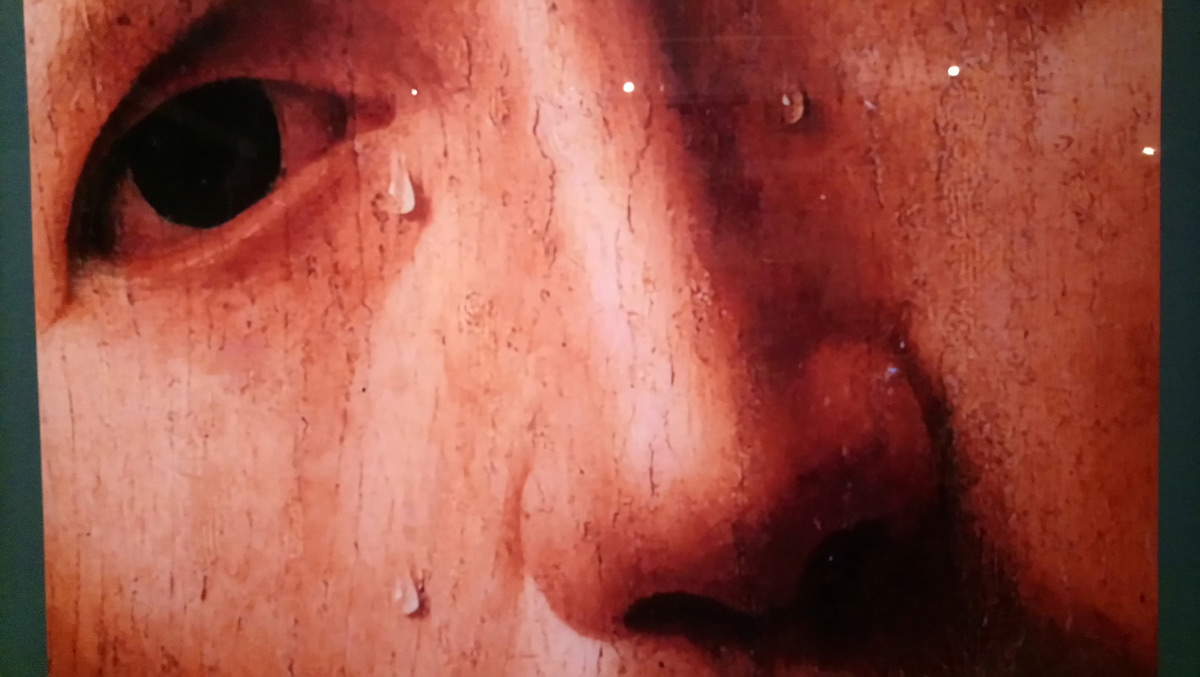

| Poster with a reproduction of a detail of theEcce Homo at the Alberoni College |

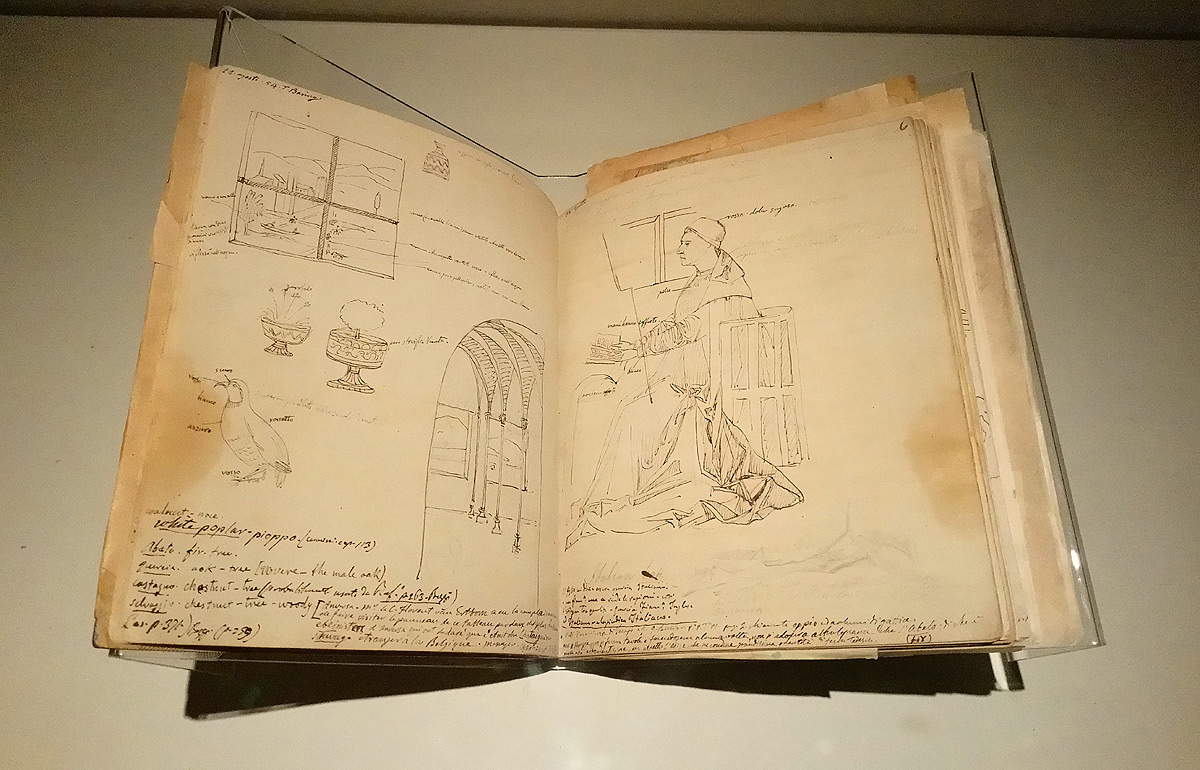

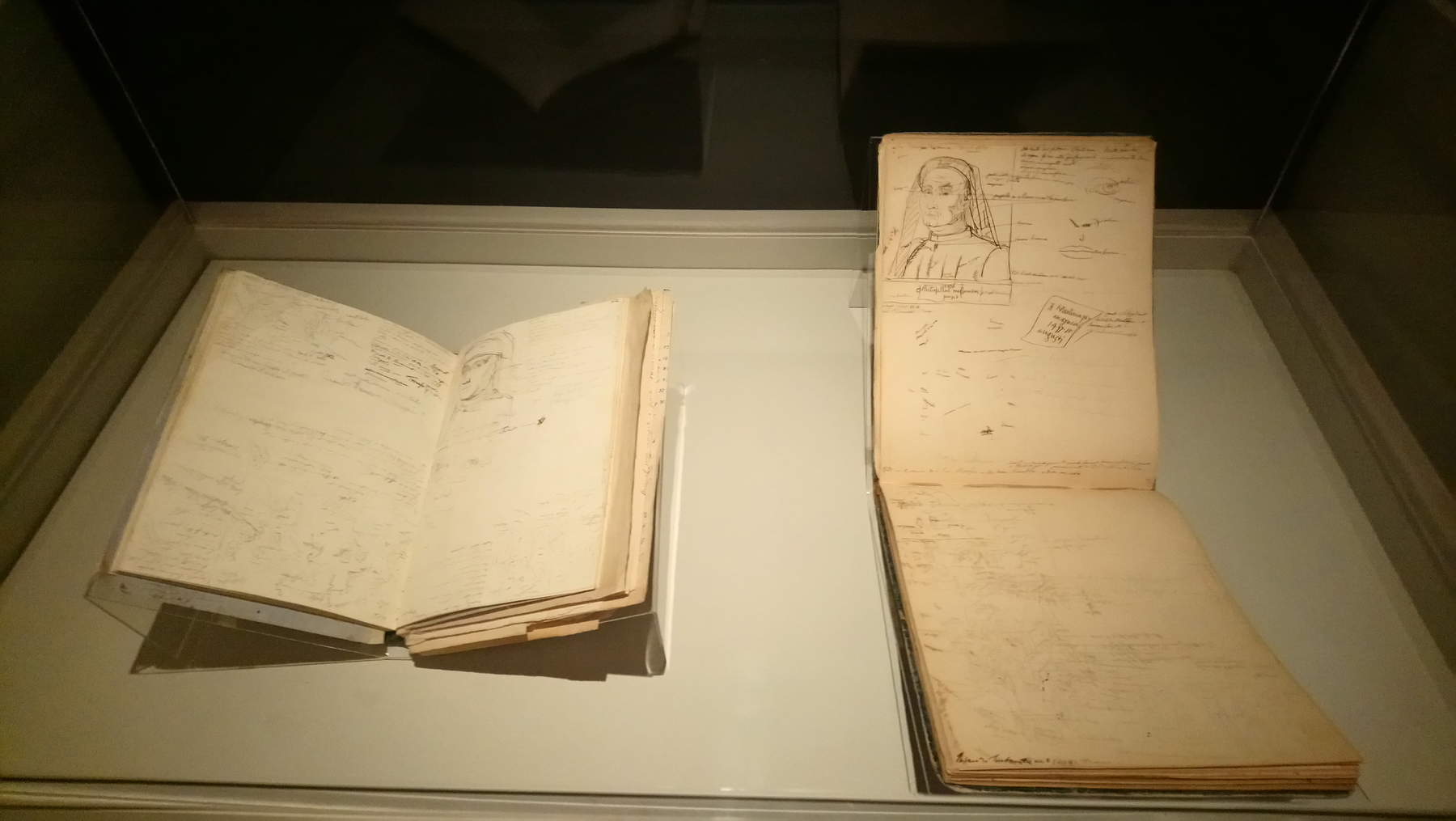

Not everything is to be thrown away, however: interesting is the idea of presenting the aforementioned notebooks of Cavalcaselle, the art historian who first reconstructed Antonello da Messina’s catalog, traveling through Italy with his notebooks in tow to profile the works he studied. The Venetian scholar was in Sicily between 1859 and 1860, and his work led him not only to search for sources and news about Antonello’s work, and to make contacts with those who owned his paintings: his notes are in fact filled with pen-and-ink reproductions, with confident strokes, of many of the Sicilian artist’s works, accompanied by comments describing their details, forms, and colors. Villa, in his essay on the catalog dedicated to Cavalcaselle’s Antonello, writes that these notes “are a privileged compass for experiencing the years in which Antonello regained the role that he deserves in the Renaissance canon. ”Indeed, the formidable art historian and traveler is credited with marking the “new reception” of Antonello, “not only reconstructing his catalog through attributions that are still accepted, but also suggesting avenues of research widely beaten by his epigones.” There are thirty sheets dedicated to Antonello in Cavalcaselle’s thirty-two notebooks preserved at the Biblioteca Marciana in Venice: the public has the opportunity to follow the “rediscovery” of Antonello by looking at Cavalcaselle’s sheets, but even this operation has not a few uncertainties.

Starting with the apparatus: Cavalcaselle’s activity is not presented within an organic framework. That is to say: in the exhibition, Cavalcaselle’s notes follow, as one might expect, the arrangement of Antonello’s works, and consequently appear more as a sort of commentary on the Renaissance painter’s work than as autonomous documents that give life to an exhibition within the exhibition. Cavalcaselle’s activity is thus broken down in a fragmentary manner, and if we add that even the itinerary among Antonello’s works, as mentioned above, appears paratactical and not very organic, the result is an unedifying overall picture, and the presence of the notebooks alone is not enough to lift the fortunes of an exhibition whose necessity was not felt. It would have been much more interesting if the notebooks had been devoted to a separate exhibition, which, admittedly, would have paid the price of poor public appeal (many visitors do not even pay attention to Cavalcaselle’s notes in the exhibition), but it could have provided a good opportunity for in-depth study.

|

| Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle, Sheet Dedicated to St. Jerome in the Studio. |

|

| Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle, Sheet dedicated to the Trivulzio Portrait |

|

| Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle, Sheet dedicated toEcce Homo |

The exhibition catalog is also a very disappointing publication indeed: beyond the few sharp ones (the curator’s essay dedicated to Cavalcaselle’s Antonello and the one on the Sicilian painter’s technique written by Gianluca Poldi) and a couple of passable contributions (the summary on Antonello’s monographic exhibitions, written by Gioacchino Barbera, which, however, focuses mainly on the major 1953 review and reserves few lines for the rest, and Renzo Villa’s historical reconstruction, which adds nothing new to what is known about the artist and is not even complete, but has the merit of being clear and easy for a wide audience), the rest is really negligible and forgettable. The short stories by the writers add little (one can save just the one by Jhumpa Lahiri, dedicated to the Portrait of a Young Man in Philadelphia: if nothing else, because it is a text from which one can sense the author’s emotion in being in front of the painting, and it is never obvious to communicate with words what one feels in front of a painting), the worksheets are very stringent and contain very little information, and even the catalog reproduces all the known works of Antonello, but does not specify which ones are on display. This is unacceptable. Moreover, a bibliography is totally lacking, both in the skimpy worksheets and, as is good practice, at the end of the volume.

In essence, nineteen delicate works from the second half of the fifteenth century were packed up and shipped to Milan from halfway around the world, with all the risks that travel entails (of course, it is true that if the exhibition took place, it was because the technicians of the lending entities verified that the works were in a condition to travel: but it is always better when a work remains in its place if the move is not motivated by valid scientific reasons), for a useless exhibition, which will leave little trace of itself in the studies on Antonello and the fifteenth century in southern Italy. In the end, if one wants to find a reason to visit the exhibition, the only plausible one is the convenience of not having to make a good fifteen or so trips around Italy, Europe and the world to see the works on display. And an implicit confirmation also comes when reading the institutional greeting of the mayor of Milan, Giuseppe Sala, in the catalog: “the value of the exhibition,” the first citizen specifies, "is in the possibility of stopping face to face with timeless works such as the Portrait of a Young Man from the Staatliche Museen in Berlin, the Uffizi Polyptych, the extraordinary Annunciation from the Regional Gallery of Palermo or the Crucifixion from Sibiu." The organizers, in short, gave us the pleasure of transporting a considerable nucleus of Antonello’s rare masterpieces to a single location: but was it really worth it? Were there any serious reasons for moving so many and such important works by Antonello? The answer, unfortunately, can only be negative. Because the purpose of exhibitions should not be to act as couriers, and their highest value should not lie in the opportunity to stand in front of a particular group of works. In an ideal situation, an exhibition should allow an advancement of knowledge on a subject. And the Antonello at the Royal Palace probably cannot be said to have achieved this goal.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.