What can one say about Plautilla Nelli (Florence, 1524 - 1588), the nun-artist to whom the Uffizi dedicates an interesting monographic exhibition, without falling into the petty rhetoric that speaks, perhaps a little too rashly, of ante litteram feminism, or into overestimates that risk losing sight of the historical and social context within which Plautilla found herself operating? To answer the question one can, indeed, start with a passage from Giorgio Vasari’s Lives. In particular, in the life of the sculptor Properzia de’ Rossi, the great art historian from Arezzo reviews some of the women artists of her time, or immediately preceding it, and among them is Sister Plautilla, for whom Vasari spends words of praise: “beginning little by little to draw and to imitate with colors pictures and paintings of excellent masters, she has with such diligence conducted some things, that she has made the artisans marvel.” There follows an extensive list of works in the hand of “Sister Plautilla, a nun and today prioress in the monastery of St. Catherine of Siena in Fiorenza in the square of San Marco.” One observation stands out in Vasari’s account: the fact that Plautilla had begun her artistic career by “imitating with colors pictures and paintings of excellent masters.”

|

| Exhibition Plautilla Nelli. Art and devotion in the convent in the footsteps of Savonarola, the drawing room |

The path of “imitation” was in fact the only one available to a woman at the time, should she intend to start her own artistic journey. In this sense, Plautilla (born Polissena de’ Nelli) had what to consider herself lucky: the convent of Santa Caterina, of which she became prioress, was located on the same square as the convent of San Marco, where for years one of the most up-to-date artists of the mature Renaissance, Friar Bartolomeo della Porta, had lived and worked. Plautilla never had the chance to meet him, as she was born seven years after the death of Fra’ Bartolomeo, but she knew his art very well, not least because, Vasari again tells us, the drawings of the brother-painter came to Santa Caterina “apresso a monaca che dipigne”: Plautilla is not named, but the “nun who painted” is undoubtedly her. Friar Bartholomew’s graphic collection, which Plautilla was able to study with alacrity, must have been an exceptional training ground, as well as her only way of learning to draw: for a woman, and all the more so for Plautilla who was a nun, obtaining a traditional artistic training in a studio was a decidedly arduous undertaking. Not impossible, as certain vulgate would suggest, but nonetheless very difficult: usually, women who painted came from families with an established artistic tradition, or who had strong interests in art. Cases of women able, at the time, to receive lessons from a master are recorded, but they are quite rare: to limit ourselves to Vasari’s roundup, we might just cite the examples of Sofonisba Anguissola, who was a pupil of Bernardino Campi, and Lucrezia Quistelli della Mirandola, whom the aretino asserts was a pupil of Alessandro Allori and Bronzino. Both were contemporaries of Plautilla: the difference between their experiences and that of the nun lies precisely in the fact that, while Sofonisba and Lucrezia belonged to lineages that were very open to art, which clearly did not preserve for the two young women a future made up of a monastic life, for Polissena (as well as for her sister Costanza), who came from a family of the merchant bourgeoisie of Florence, there were two options, as is clear from her father’s will, drawn up in 1534. On the one hand marriage, on the other the convent: a choice common at the time to many girls from wealthy families, such as the future Sister Plautilla was. For her, and for her sister, the doors of the convent were opened.

Attempts have been made to attribute to Plautilla an unlikely alumnuship with Friar Paulinus of Pistoia, mainly because of geographical proximity, remoteness from the evolutions that art experienced in the mid-sixteenth century, and stylistic affinities, albeit with Sister Plautilla’s obvious limitations: however, her art should not be judged by an originality that is difficult to identify (to the visitor walking through the exhibition rooms it certainly appears monotonous, tardy and repetitive, but it should also be emphasized that Plautilla was able to make her contribution in setting certain iconographic canons: this will be seen better in a moment), but rather by the role she played in the context of the time, including in reference to the artistic (and literary) production of the women’s convents of the sixteenth century. These are all issues on which a great number of studies have arisen in recent years, especially in the Anglo-Saxon area (and considerable is also the amount of research devoted to Plautilla, which has considerably intensified in recent years). The problem of Plautilla’s artistic collocation, moreover, has arisen for many of those who have analyzed her production, and they have often come to discordant results: if Andrea Muzzi has spoken of an “amateur” artist, meaning in this sense an artist belonging to that group of those who “while not practicing the profession, practiced the artistic exercise, notably drawing, for the purpose of their own intellectual elevation,” others (such as Fausta Navarro and Sheila Barker, who, moreover, are respectively curator and member of the scientific committee of the Uffizi exhibition) have emphasized the nature of Plautilla Nelli’s activity, which certainly did not limit itself to a mere individual exercise, not least because such a practice would have accorded poorly with the still Savonarolian instances of the Dominican convent of Santa Caterina. On the contrary, Plautilla’s paintings had recipients, even outside the walls of the convent: if a large part of her production was reserved for exclusive monastic devotion, the same cannot be said for some of the panels that left the monastery in order to embellish other convents, but also churches or collections of private citizens. In Perugia, for example, a Pentecost is preserved in the church of San Domenico, still two lunettes of recent attribution come from the monastery of San Salvi, and Vasari tells us of several paintings in Florentine family homes, a panel in San Giovannino, a predella with stories of Saint Zanobi painted for the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, and a “large panel” destined for the monastery of Santa Lucia.

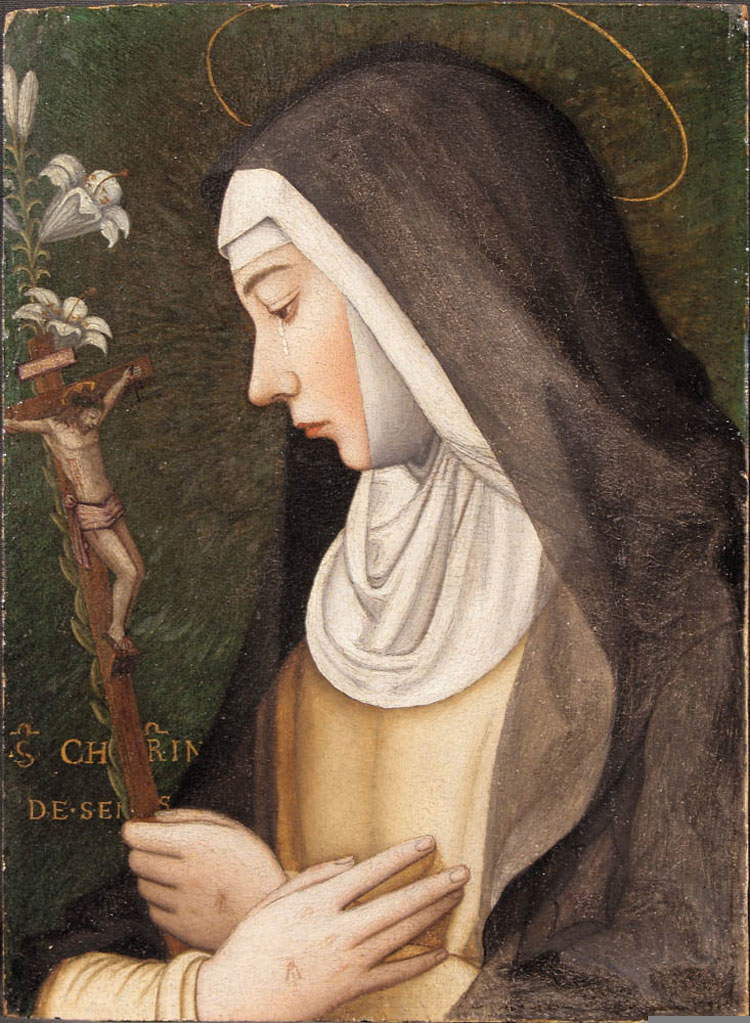

For the most part, the exhibition focuses on the “problematic” part of Plautilla’s production: while there are a few works that can be assigned to her with certainty (and which can be counted on the fingers of one hand), which are, however, absent from the exhibition, there are a good number that can nevertheless be traced back to her activity. Interesting in this sense are the paintings depicting St. Catherine of Siena, in which, on the basis of changes to the inscriptions that are often still easily distinguishable (they can also be clearly seen in the images we include in this article), we wanted to see a tribute to that Catherine de’ Ricci (Florence, 1522 - Prato, 1590) considered, because of the peculiarities of her vocation (it is said that she received the stigmata and often fell into mystical delirium), a kind of living saint: she was later actually canonized by Benedict XIV in 1746. The Church did not allow living figures to be depicted in the guise of saints: consequently, Plautilla concealed the remains of her contemporary under those of Catherine of Siena. At the origin of this series of portraits must be identified, as Fausta Navarro writes in her catalog essay, “the desire on the part of Sister Plautilla and the vast array of those who supported the ’holy nun’ [...] to support Sister Caterina de’ Ricci, who was still alive at the time, by divulging her image. Well aware of the Church’s prohibition against depicting as saints or blessed charismatic personalities venerated as such even before canonization [...] Plautilla lavished her artistic talents on founding the iconography of Sister Catherine de’ Ricci. To this end she was able to avail herself of the opportunities offered by the Catherinian model constantly observed by the ’living saints,’ the ’new Caterinas’ whose fame must have been well known to Plautilla.” We are, of course, moving in the realm of the purest hypothesis, all the more so since these are novelties that emerged on the occasion of the exhibition: however, they are suggestions that will be worth continuing to explore. The portraits of St. Catherine of Siena/de’ Ricci are all of the same type and, presumably, all taken from the same cartoon, transferred to canvas or panel by dusting: the saint, with sweet features, is portrayed in profile while adoring a lily crucifix (the lily obviously refers to the Dominican order to which both Catherine of Siena and Catherine de’ Ricci belonged). A cartoon that, with all evidence, derives from Friar Bartholomew: one has compared the profile of Plautilla’s Caterine with that of Catherine of Siena in Baccio della Porta’s Cambi Altarpiece and with that of the Madonna in the Lamentation over the Dead Christ now in the Palatine Gallery but once in the church of San Gallo, and found a perfect correspondence between the graphic reliefs of the two artists.

|

| Plautilla Nelli, Saint Catherine of Siena/de’ Ricci (second half of the 16th century; oil on panel; Florence, Museo del Cenacolo di Andrea del Sarto) |

|

| Plautilla Nelli, Saint Catherine of Siena/de ’ Ricci (second half of the 16th century; oil on panel; Assisi, Museo Diocesano) |

|

| Plautilla Nelli, Saint Catherine of Siena/de’ Ricci (second half of the 16th century; oil on canvas; Siena, Convent of San Domenico) |

The discussion thus returns, consistently, to Plautilla’s training. Given that it is now established that the nun did not train with Fra Paolino, who from 1526 to 1547 was active in Pistoia and no longer in Florence, and certainly a nun from the convent of Santa Caterina in Florence had no occasion to go to study in Pistoia, the hypothesis of self-taught training remains standing. Perhaps with the help of outside input, perhaps coming from some other nun who already knew how to paint (it is hard to imagine that Plautilla had come, as a complete self-taught, to master even the techniques of preparing materials). This hypothesis is also comforted by Vasari’s judgment that “in his works the faces and features of the women, for having seen them to his liking, are far better than the heads of men are not and more like the real thing”: Plautilla could only study the male anatomies from the drawings of her colleagues, while she obviously had the opportunity to study the women from life. Fra’ Paolino played a fundamental role in Plautilla’s life, however: it was he who, in all likelihood, gave the San Marco drawings to the young nun. The Uffizi exhibition displays a large series of drawings referable to Sister Plautilla. Of lively interest is the direct comparison with Fra Bartolomeo: a Madonna and Child by the latter is compared with a Madonna del Latte that an inscription in ancient handwriting attests to be “by Sister Plautilla pupil of the friar.” More schematic, traditional and vaguely naïve is Plautilla’s sheet, which nonetheless demonstrates good drawing skills, to which one must give credit if one thinks one is dealing with a woman to whom certain possibilities were precluded. Suffice it to look at the Bust of a Young Woman: it can be considered one of the peaks of Plautilla’s production, because in this drawing the nun, going beyond slavish imitation, reveals, as Michele Grasso noted in his essay in the catalog devoted precisely to the artist’s drawings, "a more personal stylistic trait characterized by the desire to emphasize with simplicity and immediacy a message of pietas and devotion." Doubts remain about the obvious mismatch between the sheets: those attributed to him, at least at the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe degli Uffizi, number eight, and the assignments derive from mentions by Filippo Baldinucci (who spoke of eight sheets of Plautilla at the Uffizi, without further specification) and Giuseppe Pelli Bencivenni, who also provided descriptions of the subjects and techniques.

|

| Left: Friar Bartholomew, Madonna and Child (c. 1510; black stone, white lead, stylus on cerulean paper squared with red stone, 33.8 x 23.1 cm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries, Drawings and Prints Cabinet). Right: Plautilla Nelli, Madonna of Milk (pen and ink, diluted brush and ink, black stone on paper, 26.6 x 19.1 cm; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

|

| Plautilla Nelli, Bust of Young Woman (partially diluted black stone, sfumino, white lead on paper, 31.9 x 23.1 cm; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

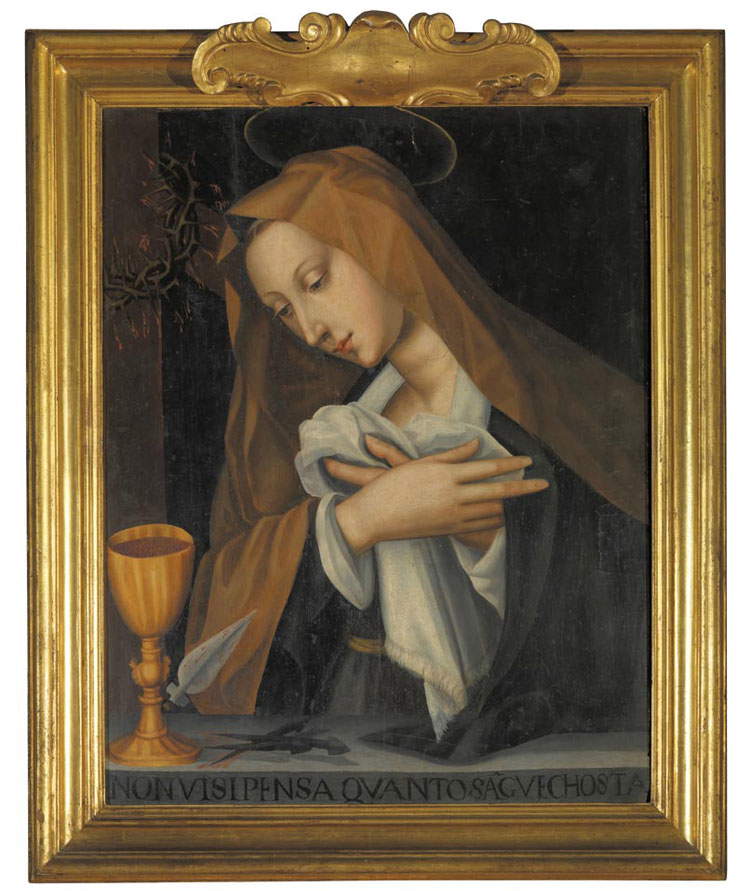

Finally, among the most noteworthy works are a Madonna in Sorrows and an antiphonary initial with a Presentation of Jesus in the Temple with two nuns. Various are the reasons for the interest of these two very different works. The first, a painting attributed to Sister Plautilla as far back as the nineteenth-century inventories of the Uffizi, is a sort of variation of a work by Alessandro Allori, taken from a larger altarpiece: it was likewise a Madonna in Sorrows that enjoyed particular fortune in the 1680s and was taken as a model by many artists, including our own Plautilla, who offers her own interpretation of the subject. The nun does not merely trace Allori’s work: a heightened patheticism shines through from the painting on display, different from Allori’s and evident especially in the abundance of tears that furrow the face of the grieving Virgin, portrayed, as the iconography intended, along with some of the instruments of the Passion (crown of thorns, chalice, spear, nails, white robe) that we notice above the shelf decorated with a quotation from Dante (“You do not think how much blood it costs”). It is an interesting example of how Plautilla, while disinterested in an updated and up-to-date art, was affected by the Counter-Reformation climate that influenced the art of the time. With the initial d’antifonario we discover instead Plautilla’s skills as a miniaturist, also recognized by Vasari. On the basis of this testimony (combined with that of Serafino Razzi, a scholar contemporary of Plautilla who likewise spoke of her talent in the field of miniature painting), and obviously on the basis of stylistic affinities with works that can be traced back to her, this Presentation in the Temple has been attributed to her, for which an early date has been proposed: not so much for the way in which the figures are depicted, which recall the composure (bordering on simplification) typical of Plautilla, as for the technical conduction that reveals a modus operandi typical of a novice painter, who in order to render the epidermis of the characters dilutes the colors to the point of exploiting, for the parts in light, the white of the parchment.

|

| Plautilla Nelli, Madonna Addolorata (c. 1582; oil on panel, 71 x 57 cm; Florence, Museo del Cenacolo di Andrea del Sarto) |

|

| Plautilla Nelli, Initial A: Presentation of Jesus in the Temple with Two Nuns (c. 1545-1557; tempera, gold leaf and ink on parchment, 58.7 x 41.4 cm; Florence, Museo di San Marco) |

The Florentine exhibition, while having to forgo the larger works (recalled, however, by a video in front of which visitors can linger in one of the four rooms dedicated to the exhibition), does an excellent job of evoking the difficulties a woman must have faced at the time, and, despite certain shortcomings (in the “supplementary” video, for example, the mention of certain works appears somewhat hasty), it succeeds in framing very well (thanks in part to the presence of Friar Bartholomew’s folios) the environment within which Plautilla’s artistic career unfolded. An exhibition that, it should be emphasized, is the result of long and above all passionate research, conducted by a largely female “team,” and still an exhibition that constitutes a significant step forward in the sphere of studies on Plautilla Nelli and, more generally, on the cultural production of women’s monasteries in sixteenth-century Florence, and that finally also contributes to open new fronts of research (the identification between Caterina da Siena and Caterina de’ Ricci has been mentioned: a topic worthy of further investigation). Plautilla can, in the meantime, boast of a record: that of being the first woman painter in Florence whose independent works we know of. And undoubtedly we can acknowledge her merits, which led even Vasari to say that Sister Plautilla “would have done marvelous things if, as men do, she had had the leisure to study et attendere al disegno e ritrarre cose vive e naturali.”

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.