To get an idea of the way in which Serafino Macchiati understood his relationship with art, one might turn to a letter that, from Paris, the artist from the Marche region sent to Livorno, addressed to Benvenuto Benvenuti, in the aftermath of an exhibition of Italian pointillists held in the French capital. It was Sept. 23, 1907: “I left, I confess, a little discouraged, not because it lacked elements of art but because I had to see once again that everything that is organized here of Italianism must always fatally abate through the fault of imbecile organizers and reckless speculators.” The fault of the artists, according to Macchiati, was their lack of originality and especially their lack of modernity. How to succeed in being a truly modern artist: this was the pain that would torment Macchiati throughout his life. Since he had begun to commit his ideas to an image, he had thought of nothing else. He had tried first with painting, always distressed by the thought of not getting to express fully what he had to say, always afraid of being cut off from the times of his contemporaneity. And he had succeeded then with illustration, a medium that at first he regarded as a sort of fallback, an expedient to be able to make a living, to be able to afford to go on with his own research, because the prejudice of the primacy of painting clouded his evaluations for a long time, and this anxiety about modernity ended up tearing at his soul. And it would certainly have ended differently if he had not reconsidered, at some point in his career, the role of illustration. It was among the pages of books that Macchiati found his reason to express himself.

This is the story told in the exhibition Serafino Macchiati. Moi et l’autre, curated by Francesca Cagianelli and Silvana Frezza Macchiati, which the Pinacoteca Comunale di Collesalvetti is hosting in its new home at Villa Carmignani, at the gates of the village, until Feb. 29. The exhibition is the result of careful and profitable research among the papers of the epistolary preserved in the Grubicy Fund of the Mart in Rovereto, much of which has yet to be studied, and which has made it possible to reconstruct the personality of Serafino Macchiati in a complete way, and as never before: what emerges is the figure of an artist who was perfectly aware of his role and place in the cultural context of the time, an educated, up-to-date artist, a connoisseur of the art and literature of his time, yet tormented and oppressed by the idea of not being sufficiently modern. “That I like in me there is only the art that I yearn to make, the painting that I always try to create, and that always eludes me, perhaps because it is too arduous an undertaking to my artistic faculties”: so Macchiati wrote to Grubicy in 1866, when he was just 25. What he liked, perhaps even he did not know. An almost irremediable bewilderment, the perception of an alleged ineptitude and the consequent disappointments, a continuous frustration that, however, became for Macchiati a vital nourishment, an unlimited fuel. Even in his years of success he will go so far as to say that he does not even know if what he does is “worth seeing,” but he is not the type to give up easily, and no matter how edgy his character may be, he hardly lets his moods get the better of him, that they end up clouding his lucidity. Macchiati spent his entire life amid the waves of an industrious melancholy that would lead him to experiment with unceasing fervor, with ardent constancy, each time elaborating new suggestions: the exhibition, with an enthralling itinerary that, with continuous changes of register, almost reflects the artist’s character, gives a way of appreciating his Impressionist gasps, his approach to Grubicy and to a singular interpretation of pointillism, his passion for spiritualism and the esoteric, and last but not least a Symbolist impulse that is perhaps the one most commonly associated with him.

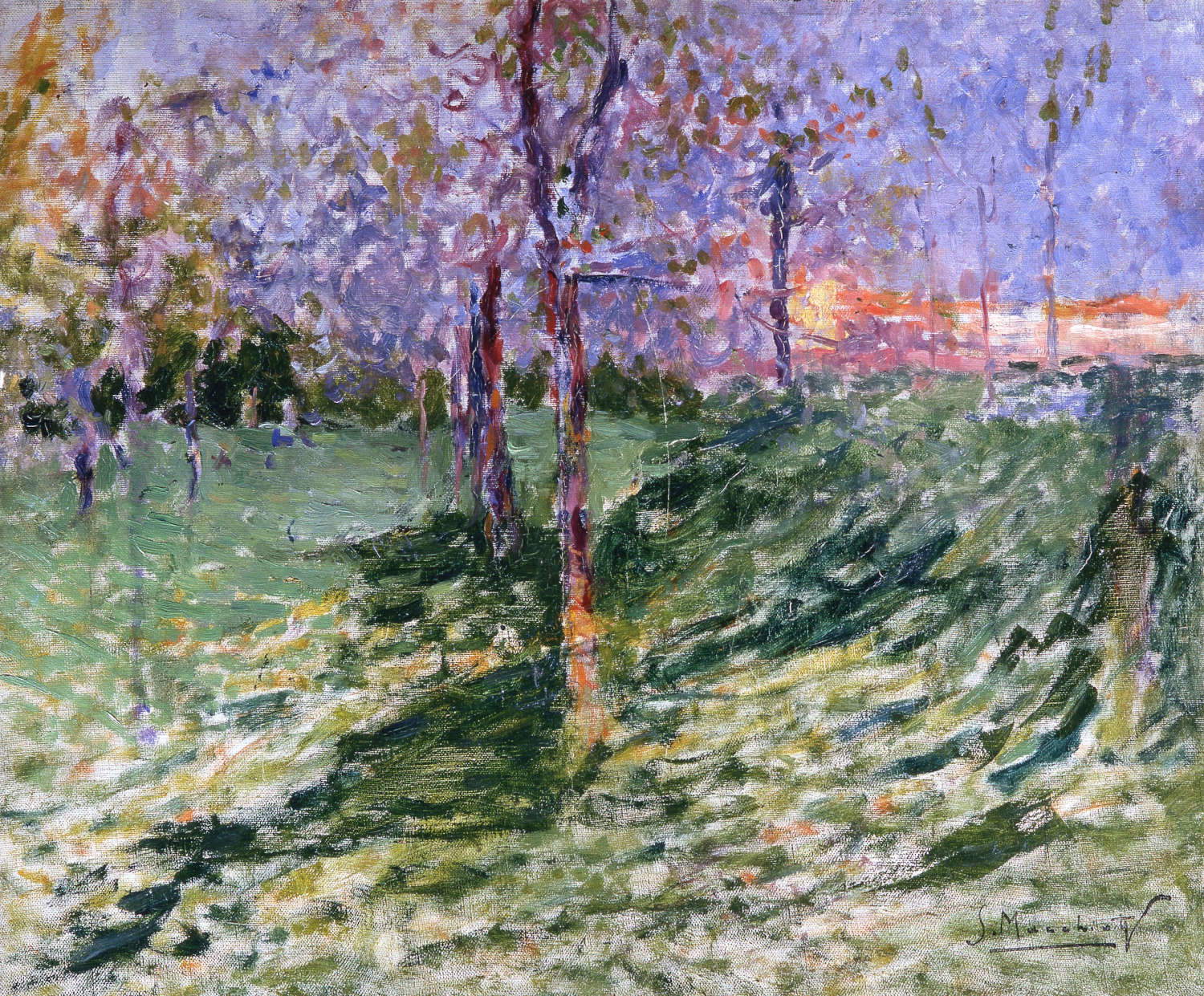

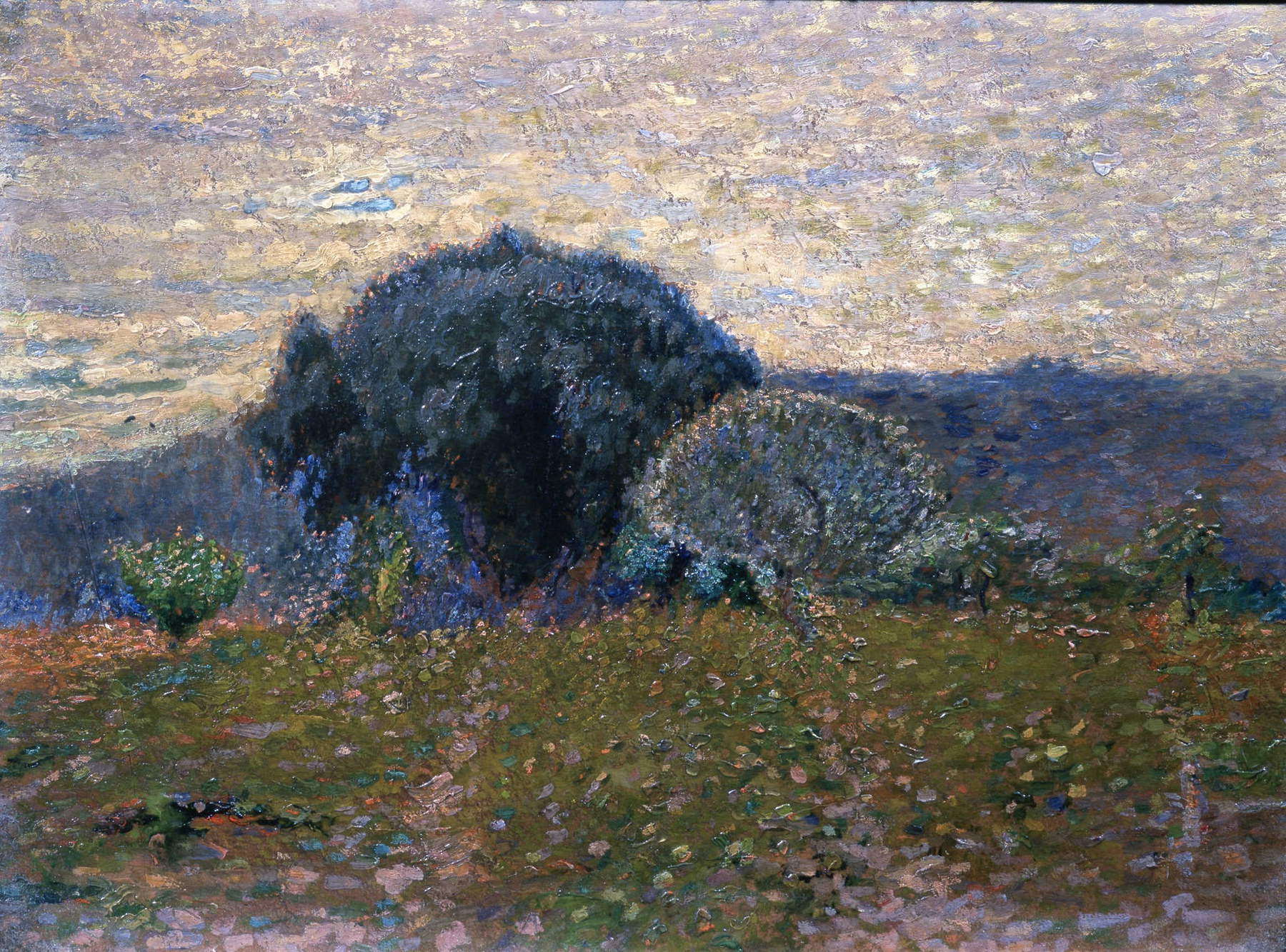

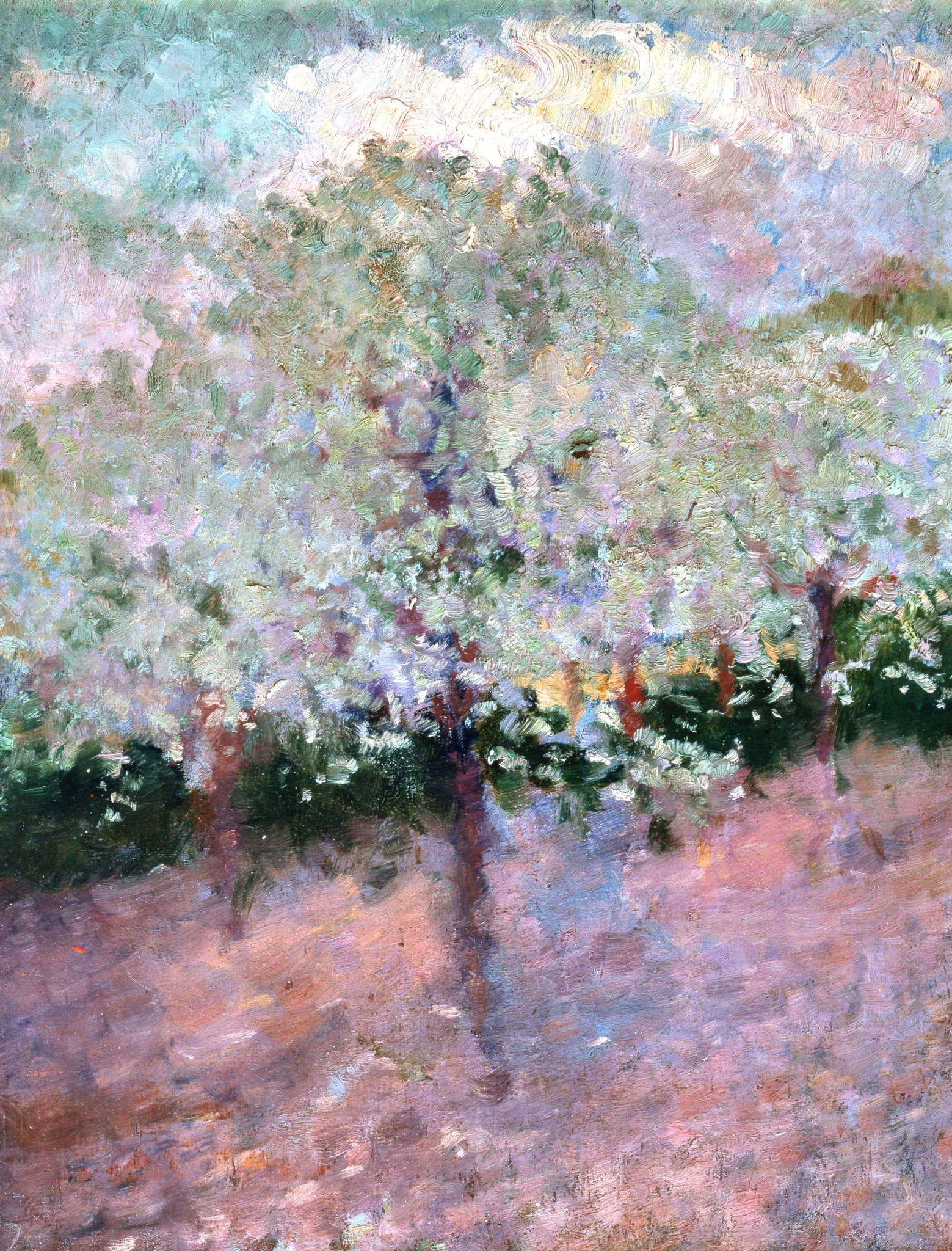

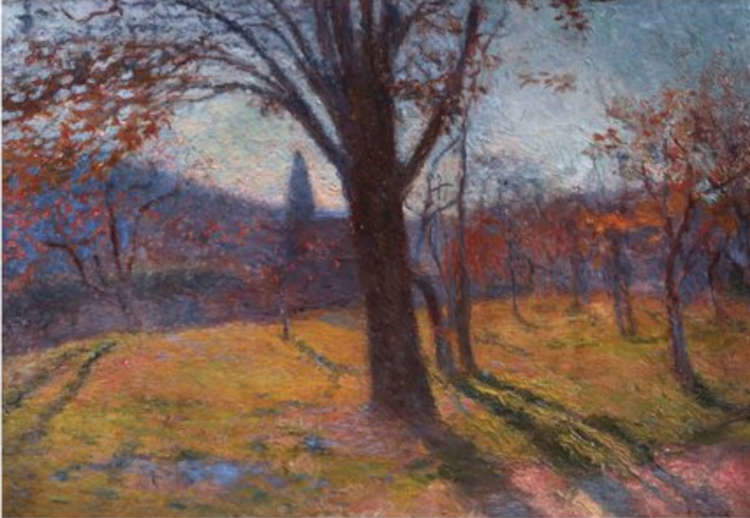

Five, in all, are the sections of the exhibition, which welcomes the public with a large room filled with views and landscapes: Under the dazzling light of the dawn of the 20th century follows the en plein air experiments of Serafino Macchiati, who thus begins, in the midst of nature, his own artistic journey. It must be said that the room does not contain the earliest paintings in the exhibition, since here we start from the late 1890s and, as we will discover as the tour continues, the principle of Macchiati’s torments was well before that: the artist’s attitude, however, had remained unchanged from his beginnings. Curiously, what led him toward the exploration of nature was the theater, for he believed that the theater was nothing but a representation of life, albeit paler than the real thing, than nature. Hence, the need for a deeper involvement that Macchiati experiences by immersing himself in the woods and countryside. “For a long time,” he wrote again to Grubicy on March 25, 1900, “I have only seen and understood the theater and through the theater Nature.” His landscape works are for the most part paintings of sketchy intonation, and this applies as much to the works that the artist painted letting himself be inspired by the Roman countryside (although for health reasons he could not spend too much time outdoorsoutdoors and was often forced to give vent to his ideas indoors in the studio), as seen in Parterre di fiori or La grande nuvola, as much as for those executed in Paris after having seen the works of the Impressionists up close(Landscape at Mougins, Les deux mimosas or Bord de mer). They must be seen above all as research, as works that were not born to be shown to an audience or to be finished (the only truly completed one perhaps being the Autumn Afternoon of 1902, owned by the Enrico Piceni Foundation), as experiments now on light and color, now on the medium (Macchiati passed with agility from pastel to canvas), now on the brushstroke that becomes at times more liquid and distended and at other times more fragmented and close to pointillism, now on the layout (which at times even reaches unexpected and daring results, close to those of photography, as happens in Bord de mer). Landscapes thus frame Macchiati’s temperament, which in this period of his life is still kindled by the flame of impression: “The more the eye becomes accustomed to a given setting and intonation - the more it loses of the first impression - which is the true and proper expression that is released from a given effect to tickle to painting.”

Macchiati was already on the road to the coveted modernity, and he had already demonstrated this with the works that the exhibition brings together in the second section, "Making of the living, living that speaks." The dream of a “painting transpiring life,” where the audience gets to see the production most marked by its proximity to Vittore Grubicy, with works dating back to the 1880s. However, these are works that also look to a verista such as Antonio Mancini, one of the few contemporary painters who manage to capture Macchiati, as according to him among the few to paint figures “alive palpitating with truth.” From such a singular fusion the originality of Macchiati’s pointillism. In these paintings, writes curator Cagianelli, the painter "is certain that he has identified the right direction: one must therefore read in the context of this complex phase of transition the series of portraits inaugurated by Paolina Brancaleoni, Umberto’s mother (1887) and continued with some studies of heads" such as the Peasant of Rocca di Papa, the Portrait of the son in frame or theSelf-Portrait all circa 1888, and all works “conceived at the dawn of the pictorial conversion to modernity,” as portraits of characters captured from life, in an attempt to capture them in their context, to frame them in their environment.

Serafino Macchiati,

Serafino Macchiati, Serafino Macchiati,

Serafino Macchiati, Serafino Macchiati,

Serafino Macchiati, Serafino Macchiati,

Serafino Macchiati,

Precisely the environment is the strand of the third section, The Contradictions of the Belle Époque: From the Conquest of the City to the Exploration of the Psyche, which acts as a seam between the first and second parts of the exhibition, allowing us first to admire a rather sunny Macchiati, the one who roams the squares of Rome with theidea of recording, with his own brush, the liveliness of the capital’s urban environments (the Roman piazzas, the artist will confess, are for him a sort of “baptism that will give me courage for other more difficult attempts”), as seen in one of the symbolic works of the Collesalvetti exhibition, namely the Lady with a Fan in the Square (and he would do the same in Paris, where he had moved in 1898 to work as an illustrator), and then an artist who begins to lose himself in the darkest folds darkest folds of the human soul, which is the Morphinomaniac Stains, one of his best-known works, a portrait of two women who have taken the well-known opiate, which at the time was particularly prevalent both in Belle Époque high society and among the last: the work, like several of Macchiati’s canvases, was probably conceived as an illustration for a book, a field to which the artist would devote the entire last period of his career, recognizing, after having long underestimated this medium of expression, that theillustration has first of all its own very noble autonomy and that it should not be considered a fallback for an artist, and then that it is perhaps the most suitable tool to describe modern society. This awareness matured at the beginning of the twentieth century and perhaps found its decisive moment, at least according to the idea of Francesca Cagianelli, when Macchiati was faced with the illustrations for the novel Moi et l’autre by Jules Claretie, an undertaking that offered the artist the opportunity to probe the full potential of ’illustration (not only the artistic ones, but also the social ones), and to discover in an accomplished way his own vocation, which, however, had already been fully recognized to him by Vittorio Pica as early as 1904, the year in which a decisive article came out in Emporium both to understand the scope of Macchiati’s art and to frame his now defined artistic personality.

The artist from the Marche region had persuaded himself, Pica wrote, “that especially in our age, in which every year thousands and thousands of paintings and statues are created, which serve no other purpose than to clutter the halls of the all too frequent art exhibitions and no one knows where they end up, a gracefully illustrated volume is certainly not worth less than a good painting.” Pica, moreover, saw in Macchiati a “a virtuosity of elegant reproducer [...] of the scenes and figures of the bustling existence of the modern city,” as well as a “casual illustrator” equipped with essentially two merits: “naturalness in attitudes” and the ability to place his figures “in the most suitable environment to determine the type and to make understood the psychological state they go through.” Seraphim Macchiati, at those chronological heights, had already transformed himself: leaving behind aspirations to a monumental painting, never materialized, and abandoning the idea of finding his way through the paintbrush, the artist distinguished himself as a refined illustrator, who emerged above the ranks of those who worked for the magazines of the time to become at the same time artist, psychologist, sociologist, careful investigator of the society of the early twentieth century with the medium of ’illustration, seen not as a mere translation through images of a page of a book, but as an art in its own right that starts from the literary narrative to offer an interpretation of the reality that lives and pulsates in the artist’s mind, and that is nourished by his ideas, his suggestions, the cues he grasps while observing the art of his time. “He who illustrates literary composition,” journalist Carlo Gaspare Sarti would have observed in an article on Macchiati published in 1912 in We and the World, “performs a work of investigation and penetration that is all the more torturous the more deeper; the artist who collaborates with the pencil in the chronicler’s narrative or the novelist’s invention must identify himself with the characters of these writers and live, as it were, the situations they have reproduced or devised.”

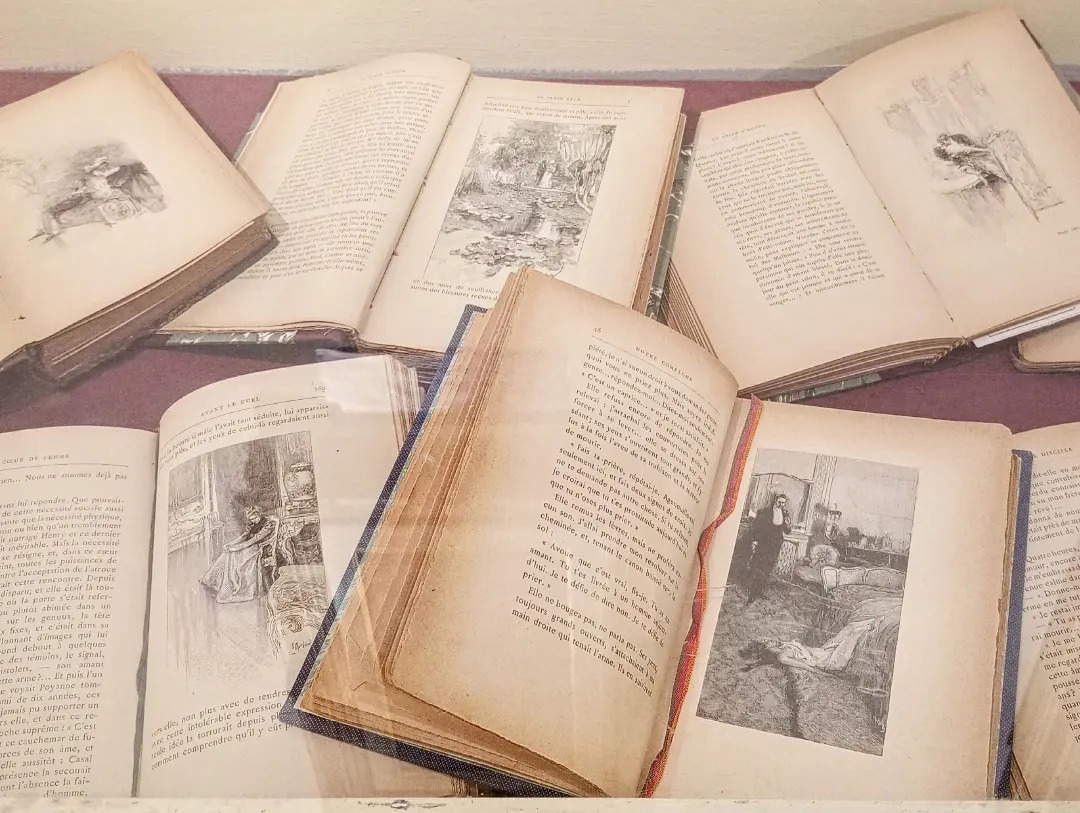

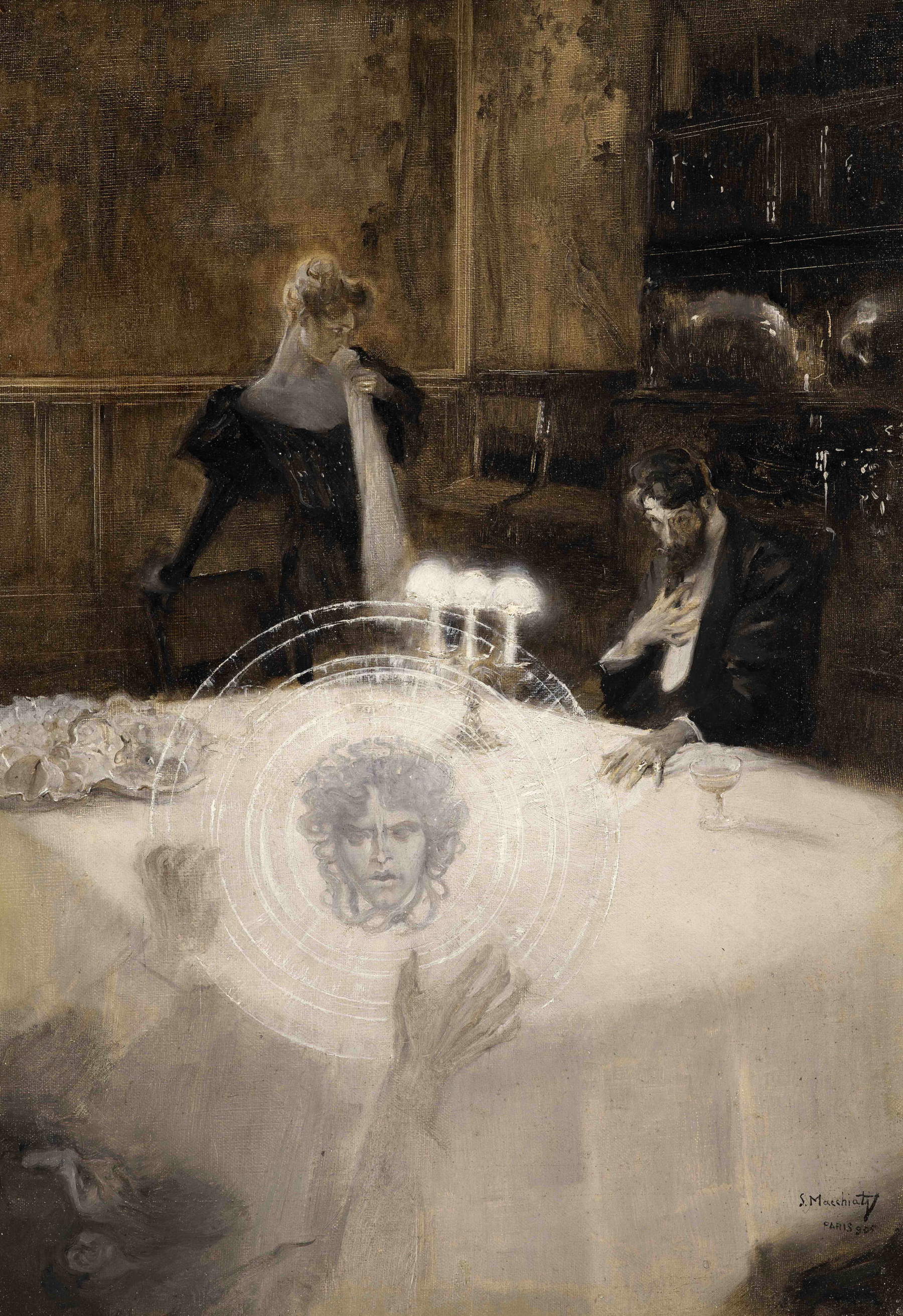

Therefore, illustration cannot but be the protagonist of the fourth section of the exhibition, entitled The Battle for "The Illustration of Thought ." From “La Tribuna illustrata” to “Je sais tout,” which collects magazines and books illustrated by Macchiati (including a cover of Noi e il mondo rediscovered on the occasion of the Collesalvetti exhibition), as well as sketches for the images that later ended up in print. According to the opinion of Dario Matteoni, who in the catalog signs a contribution dedicated to the illustrator Macchiati, it is in the images painted for the magazine Je sais tout, and in particular in those for the novel Moi et l’autre, a work that tells a story of split personalities, that a useful key to understanding much of the artist’s illustrated production can be found, since it is above all in these plates that Macchiati mixes the real with the fantastic, truth with dreams, fact with ideas, sometimes yielding to Symbolist reminiscences (this is demonstrated in the exhibition itinerary by a scene filled with oneiric and visionary pathos such as L’avertissement, an illustration for Moi et l’autre from which a certain taste for the horrific also shines through), and at other times to esoteric and spiritist imagery, in keeping with the fashions of the time. Resorting to these hallucinated visions, however, was not a way to evade reality, or to escape from the everyday, far from it: it was Macchiati’s way of criticizing the excesses and contradictions of the society of his time. And it is with this highly original look at contemporary society that Macchiati recomposes the seemingly incurable rift between painting and illustration. A work that recently reappeared on the market, L’Aimant, shown at the recently concluded Umberto Boccioni exhibition at the Magnani-Rocca Foundation, was identified in the exhibition as a sketch for an illustration included in an investigation, titled Les grandes spéculations, published in 1905 in Je sais tout (the magazine open to the illustration page is on display): the image was a kind of denunciation in regard to speculators, alluded to by the character intent on looking at the money on the table, and behind whom loom some monstrous figures of skeletons and ghosts, symbols of the misfortunes and ruin awaiting the speculators (“In what deep and intolerable anguish would the speculators live”, reads the caption accompanying the illustration, “if they knew all the dangers, all the misfortunes that await them, ready to swoop down upon them to destroy their destinies, those of the beings dear to them, those of the thousands of men who have trusted them.”) And it is precisely to one of the vizîs of Belle Époque society, substance abuse, and in particular morphine, that the last section(Artificial Paradises of Decadence) is dedicated, anticipated by the Morphinomaniacs that the audience saw in the previous room. Curated by Emanuele Bardazzi, the section takes its cue precisely from Macchiati’s painting to propose to the public a series of graphic works by artists such as Félicien Rops, Henry De Groux, Alfredo Müller, and Anders Zorn, all related to the consumption of morphine and absinthe.

Serafino

Serafino

The Collesalvetti exhibition does not fail to frame Macchiati’s production within the boundaries of literature, especially in the last sections: vivid the presence of Charles Baudelaire and the crushing inner emptiness that overflows from the pages of Les Fleurs du Mal (in the exhibition, in the last room, there is also an illustration by Jean Veber for L’ennui), it is difficult not to think, in front of the most gloom of Macchiati, to the hallucinated loneliness of Des Esseintes in Huysmans’ Countercurrent, unfailing references to writers who confronted the Belle Époque’s passion for opiates (such as Victorien De Saussay, who wrote a novel entitled La morphine). Nor is there any shortage of references to Livorno, although superficially one might think that Macchiati had little to do with the Tuscan city: in fact, the artist’s frequent contacts with the milieu of Caffè Bardi, the meeting place opened in 1908 that immediately became a sort of cenacle of the most shrewd Leghorn artists of the time, are well known.period, from Gino Romiti to Renato Natali, from Benvenuto Benvenuti to Mario Puccini, from Gastone Razzaguta to Manlio Martinelli (an environment with which Macchiati shared, for example, an interest in themes related to the occult), and it is also known that Macchiati had very solid relations with the entire Livorno Divisionist milieu close to Grubicy, in particular with Benvenuto Benvenuti. And in turn Macchiati would sometimes have represented a point of reference for Leghorn artists, for example when, Francesca Cagianelli recalls, as a result of an exchange between the Marche artist and Benvenuti he penetrated “into the Livorno of Caffè Bardi the echo of the debate on Futurist art,” which had started from a controversy over an article by Ardengo Soffici that dismissed both Grubicy, Benvenuti, and Macchiati in a rather brutal manner. Who would later respond in kind.

This is a good result for the Pinacoteca di Collesalvetti, which, on an annual basis, and even in the cramped conditions that notoriously torment small provincial museums, manages to illuminate forgotten histories of some little-known protagonists of theTuscan art between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and the exhibition on Macchiati goes to compose a sort of ideal triptych, together with the reviews on Charles Doudelet in 2022 and on Gino Romiti in 2023, on those artists more or less linked to Livorno circles of the early twentieth century who were seduced by the Symbolist verbo. All of this is always accompanied by rich catalogs (the one of this year’s exhibition, in addition to a long essay by Cagianelli, contains a new biography of the artist written by Silvana Frezza Macchiati and contributions by Dario Matteoni, Camilla Testi and Emanuela Bardazzi to compose a complete picture on Macchiati). Finally, it should be noted that the review will not fail to surprise the public then, we are sure, because of its topicality: how many artists today care to pose the same problem of modernity that had plagued Macchiati throughout his career?

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.