Can a figure like Dante Alighieri who lived between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries and passed away a full seven hundred years ago be considered pop? This is what the exhibition running until January 9, 2022 at the MAR in Ravenna, entitled Un’Epopea Pop, with which the city where the Supreme Poet died and where his tomb is located concludes the exhibition cycle Dante. The Eyes and the Mind promoted by the Municipality of Ravenna - Department of Culture, organized by the MAR - Art Museum of the City of Ravenna and realized with the support and patronage of the Emilia-Romagna Region, Dante 2021, the National Committee for the Celebration of 700 Years - Ministry of Culture, with the contribution of the Fondazione del Monte di Bologna e Ravenna and the Ravenna Chamber of Commerce, and under the patronage of the Italian Dante Society.

In the introductory note to the exhibition, curator Giuseppe Antonelli points out how Dante’s popular fortune began as early as the 14th century, reaching all the way to the present day, and how it has involved various spheres such as literature, cinema, music, art, and video games. In fact, Dante has become a true icon not only in Italy, but all over the world: the image of Dante is indeed a symbol ofItalian and European cultural identity, but it has also spread to advertising, movies, games, and has also made its way into multimedia and interactive content. This is why the Ravenna exhibition is built according to the various areas of study: it begins with the Dante a memoria section, as the Supreme Poet fully belongs to our collective memory (think of how the verses of the Divine Comedy, and in particular the incipit, are really known by everyone). Petrarch recounts in a manuscript how Dante’s verses were mispronounced by certain Florentines, and there is even testimony of a carver who ended up hospitalized in an asylum in the late 19th century after attempting to memorize the entire Divine Comedy. It then moves on to the Dante in pictures section with the various editions of the Commedia illustrated (famous is the one by Gustave Doré or the illustrations by Francesco Scaramuzza), but do not forget how Dante images also spread through postcards, calendars and other media such as magic lantern slides. It goes on to show how cinema, from silent to sound via video art, has contributed to the spread of scenes from Dante’s Inferno: featured here are clips from theInferno filmed by Francesco Bertolini, Giuseppe de Liguoro and Adolfo Padovan in 1911 to somewhat more recent ones from episodes of A TV Dante: the Inferno Cantos I-VIII by Peter Greenway and Tom Phillips from 1989.

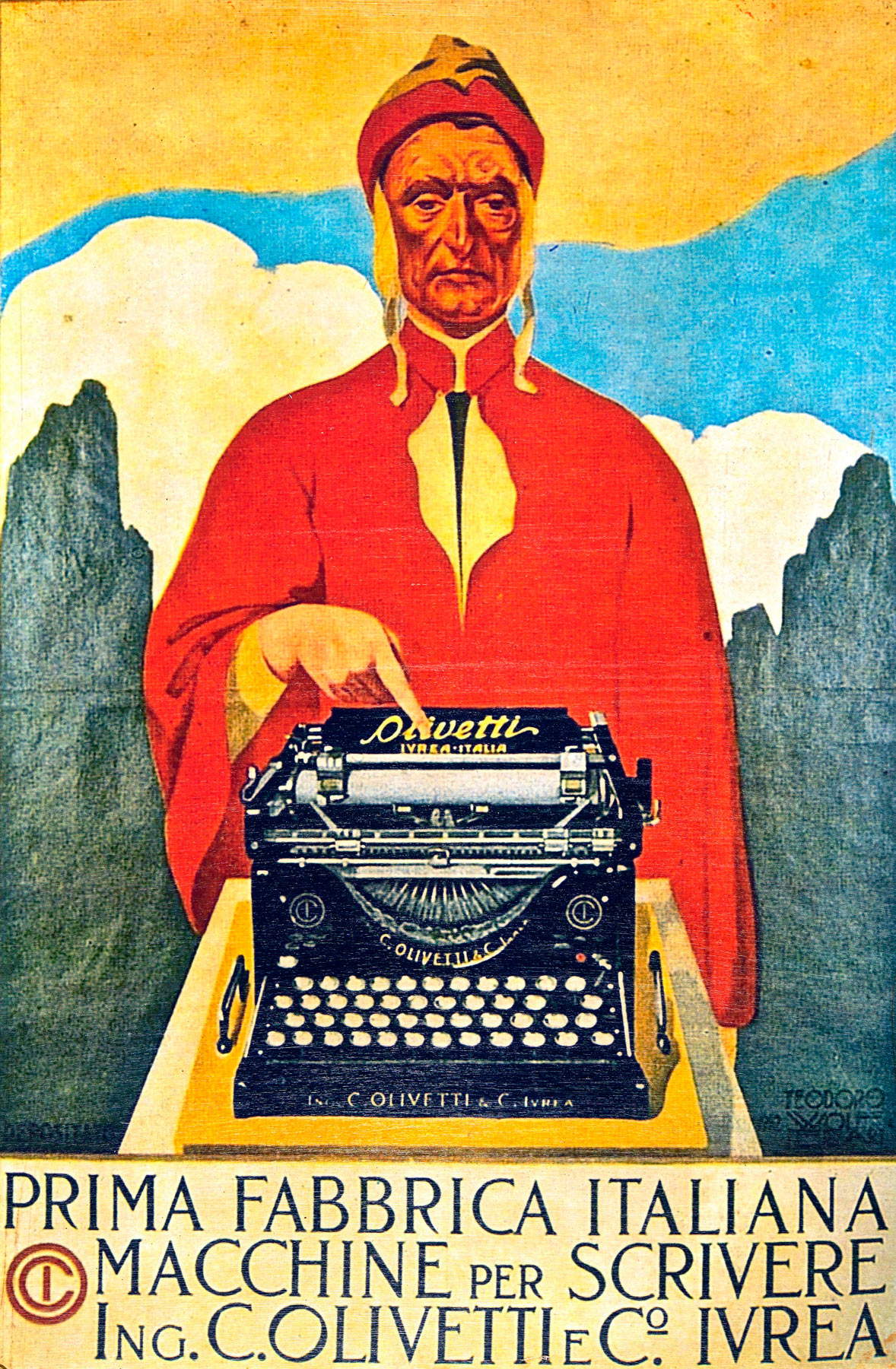

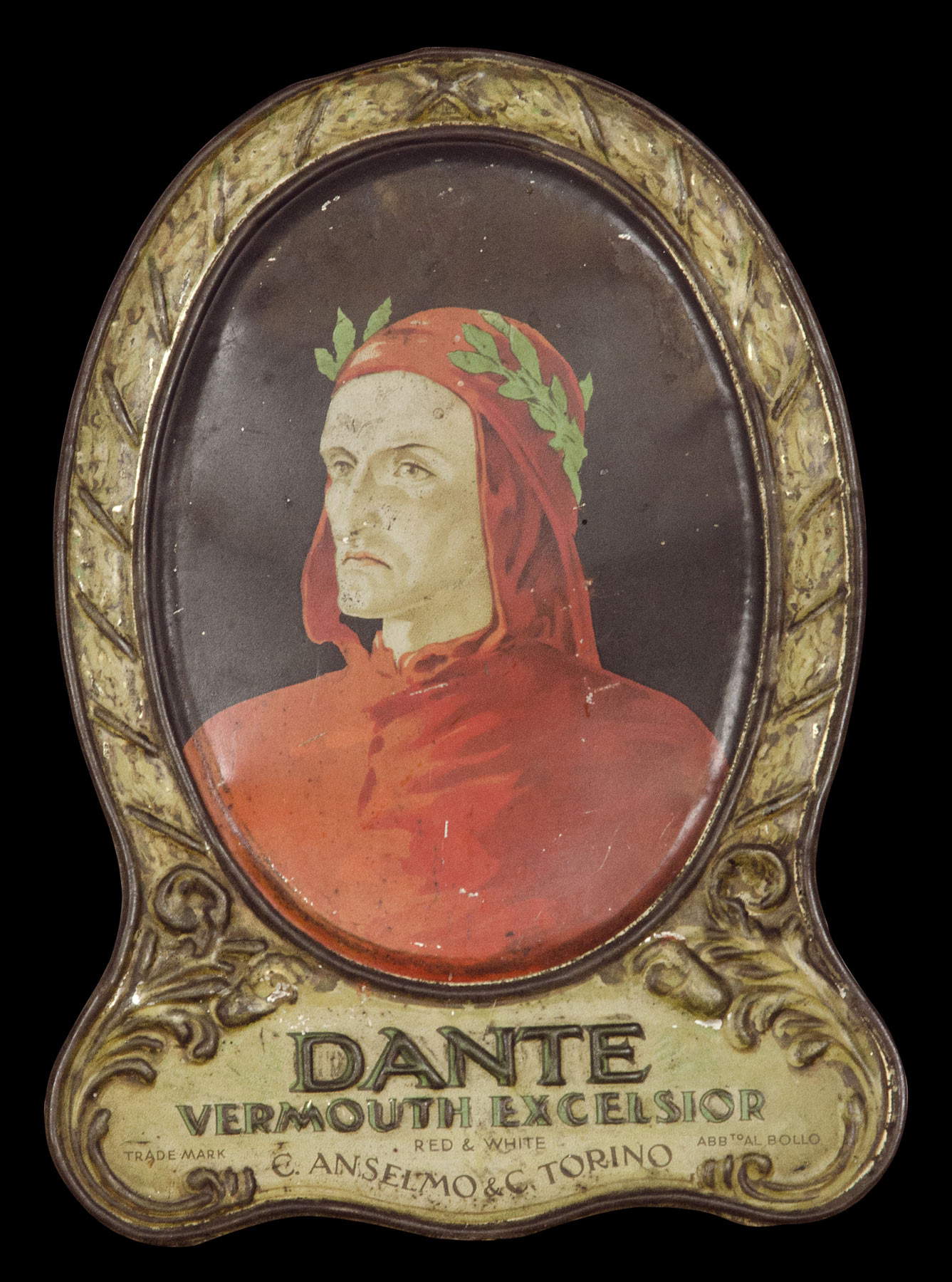

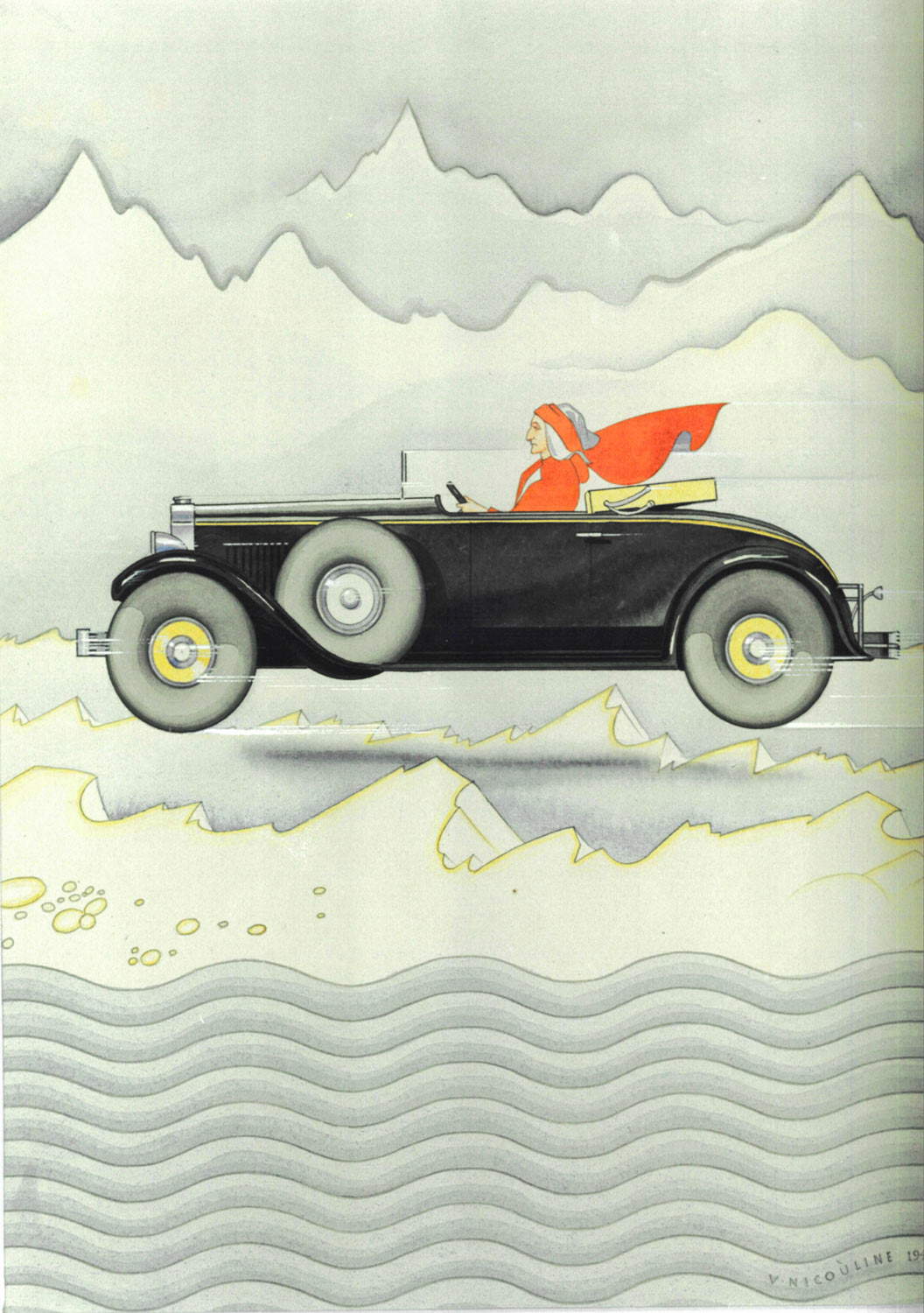

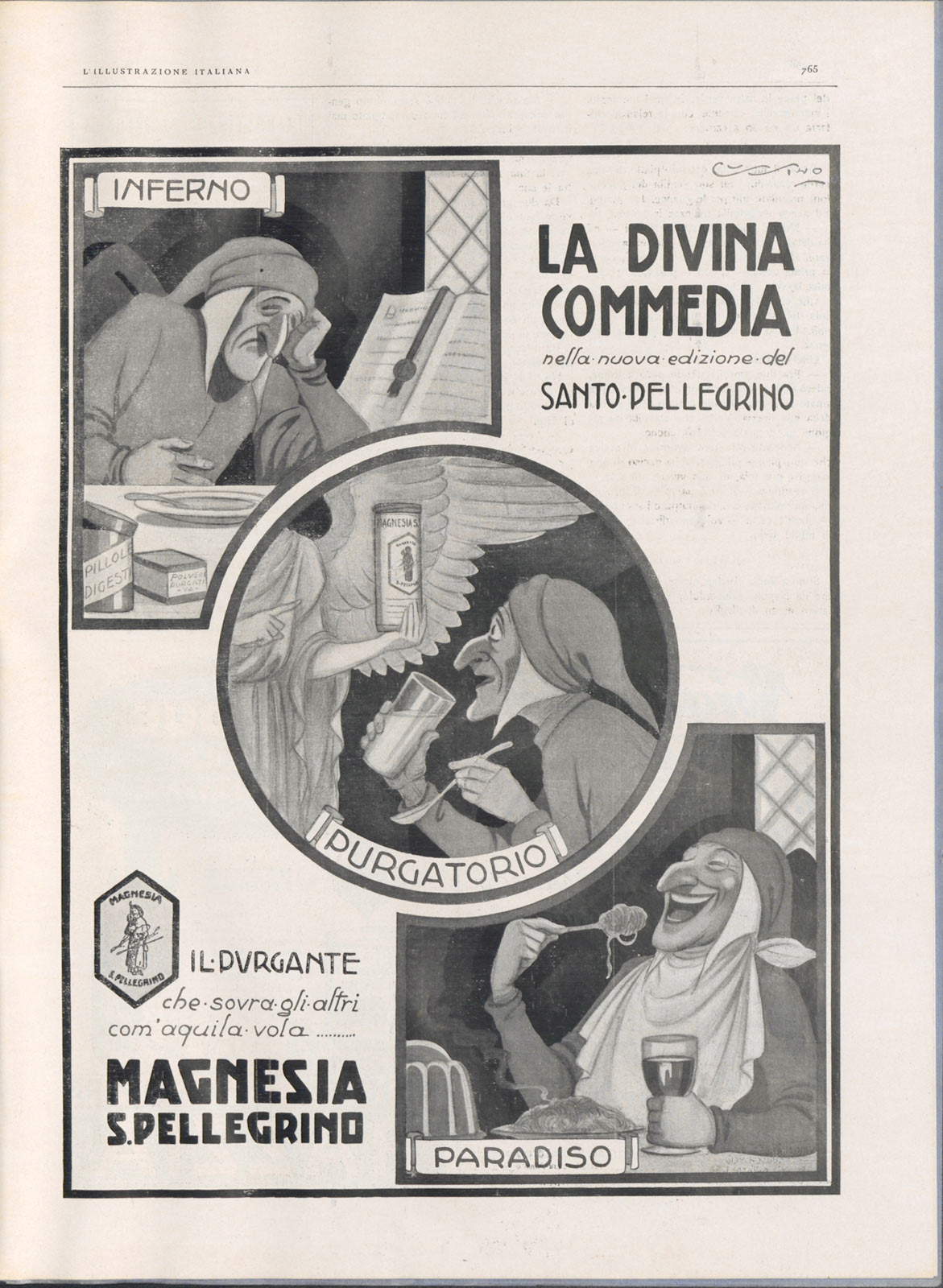

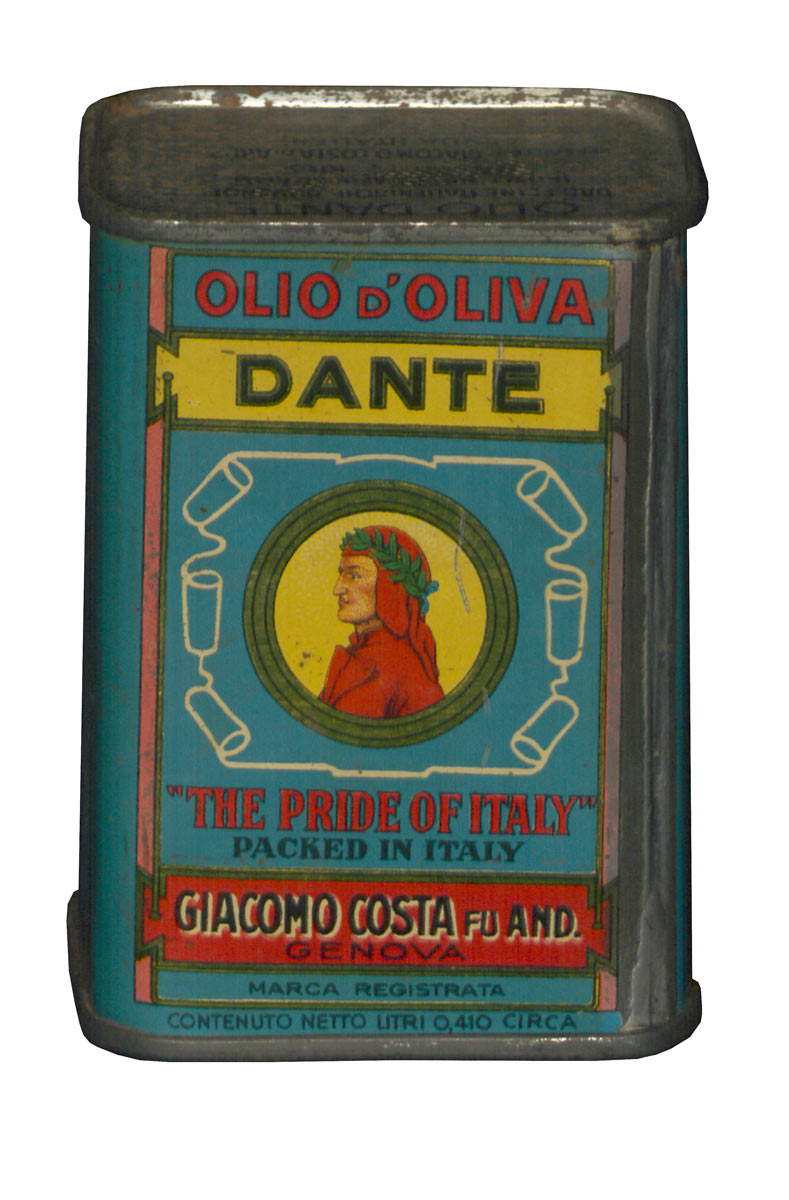

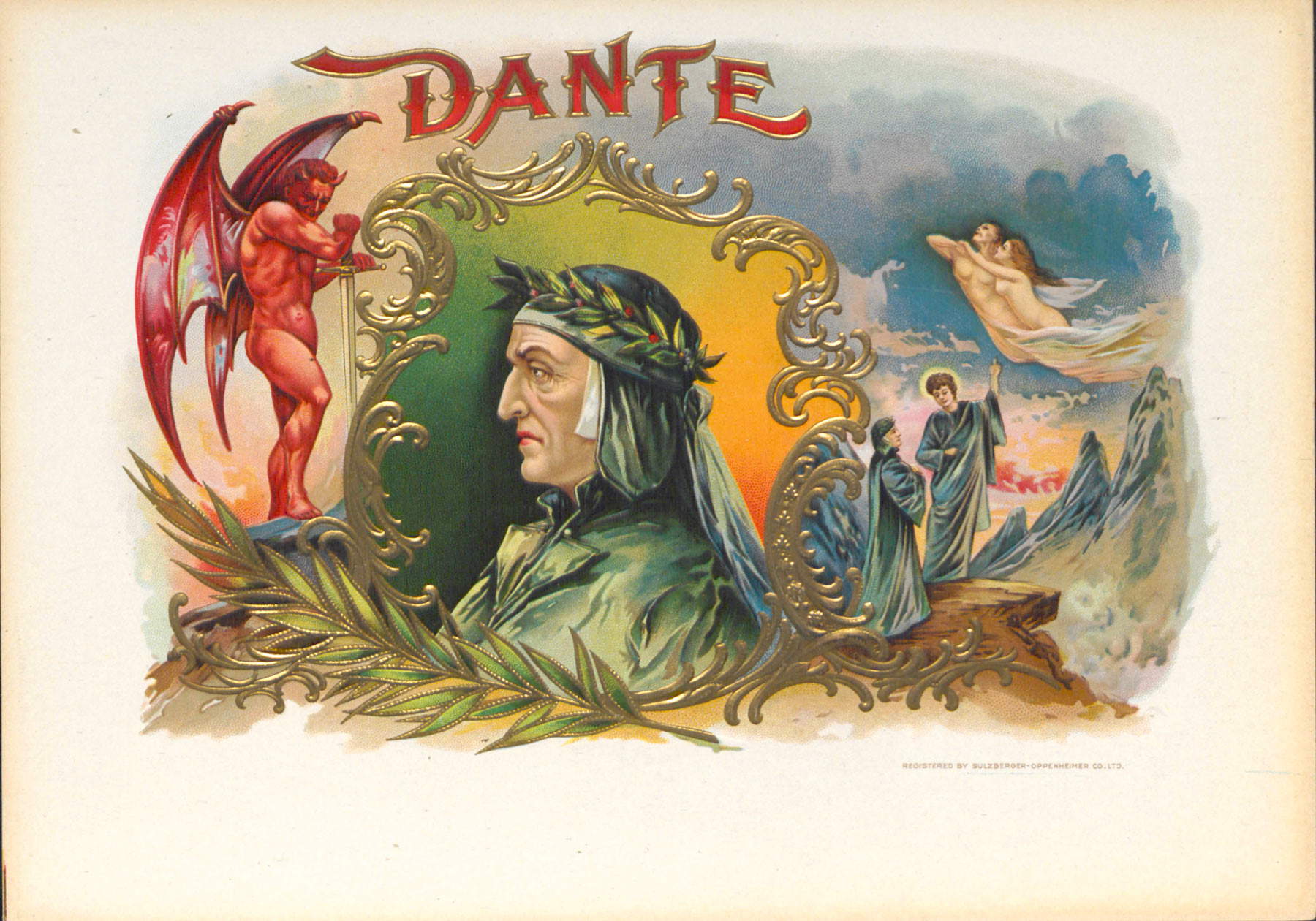

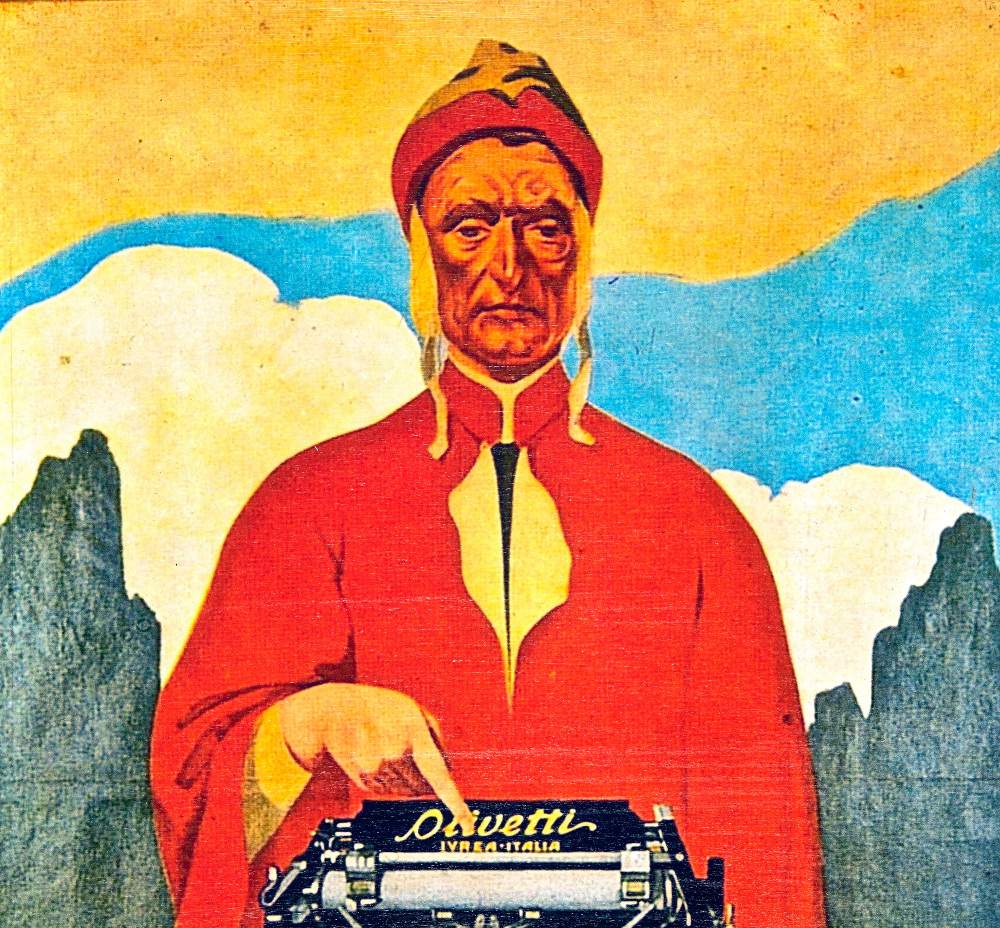

Even Dante and the Divine Comedy have not escaped parody, and so various artists, especially cartoonists, have reinterpreted and reworked the Comedy: examples are Jacovitti’s 1947 strips andMickey’s Inferno from 1949-1950. Parodies are the Divine Comedy expounded and commented on in Florentine sonnets or the Goliardic Translation in Piedmontese dialect, Cattivik in Purgatory and Paradise; as well as comic films such as Totò all’Inferno (1955) or TV gags such as L’Inferno in 6 minutes sung by Oblivion (2011). In the Dante at play section, the figure of Dante appears on poker cards or board games and even becomes the protagonist of video games such as Dante’s Inferno for PlayStation and Xbox. And in Dante for Sale we show how advertising has used the poet’s name and image, sometimes even in bizarre ways: from 1929 Liebig figurines, to advertising postcards for Magnesia San Pellegrino, Dante oil, Dante Vermouth Excelsior to shaving razor blades, cigar box, automobile factory and Olivetti typewriter. Many Dante-themed cartoons also had actors such as Vittorio Gassman and Walter Chiari as protagonists.

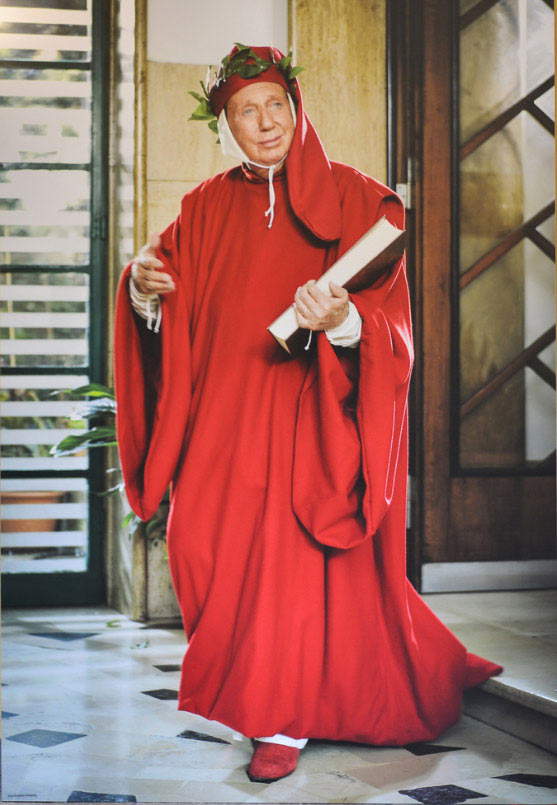

The curator also wanted to recount the Dante character, the protagonist of numerous anecdotes about his life, through 14th-century novellas, ancient commentaries, 17th-century books of fairy tales, 19th-century stories and children’s magazines; the section closes with the 1955 Istituto Luce April Fool’s prank featuring the fake discovery of Dante’s personal belongings on the banks of the Arno. The tale of Dante pop continues with the Dante icon section in which various ancient portraits of the Poet are presented, although even today the true appearance of his face is unknown (what is associated with him is actually the result of reconstructions and descriptions, literary and oral), and stamps, coins and banknotes depicting him.

Inevitably, the school setting could not be neglected: in all schools the Supreme Poet has always been studied, starting with editions designed for children and young people. The last room of the exhibition is dedicated to theencounter between Dante and Beatrice narrated through more than a hundred works and objects, such as postcards, posters, cookie and matchboxes reproducing Henry Holiday’s 19th-century painting. Closing the exhibition is Umberto Eco ’simpossible interview with Beatrice Portinari from 1975 in which she complains about Dante’s courtship bordering on obsession. Accompanying the visit are the voices of great performers who have tried their hand at the lectura Dantis.

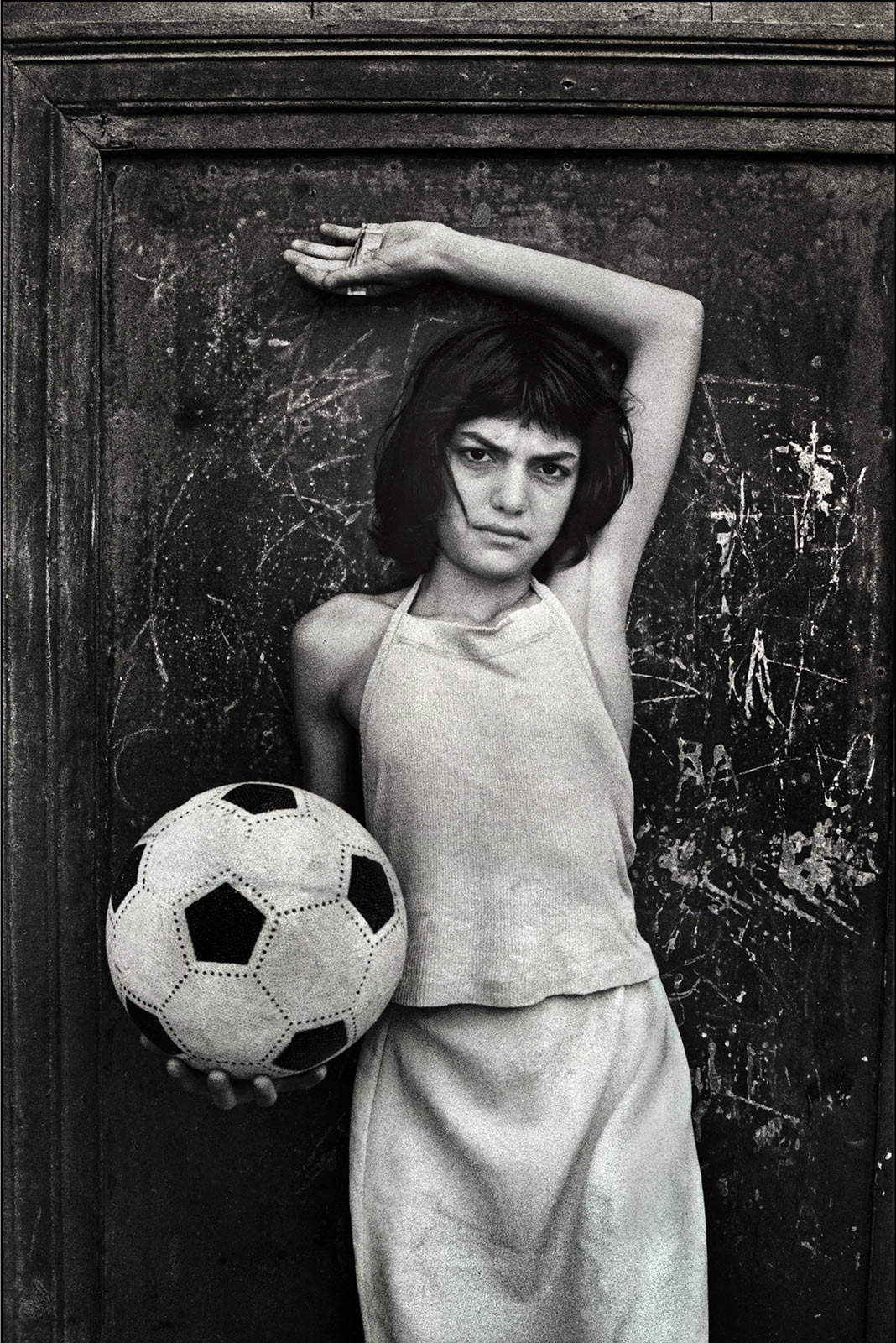

The entire exhibition is also intertwined with an itinerary curated by Giorgia Salerno that aims to reread Dante in a contemporary key. A path in which, as explained by the curator, it is intended to experiment with a new reading of the Comedy by placing the world of contemporary art in direct relation with that of literature and poetry, both of which are prone to imaginative capacity. If in the tradition of Dante’s illustration, images figuratively recounted Dante’s text canto by canto, in contemporary art it is the works that interpret themes and characters from Dante’s text, allowing themselves to evoke and narrate the Comedy. Visitors are thus accompanied along the exhibition route by guiding themes, such as Souls, Journey, Female Figures, Dream and Light. One or more artists have been chosen for each of these themes, with the aim of reinterpreting through works the places and characters of Dante’s text, guiding the visitor inside the Comedy through installations, sculptures, paintings and photographs.

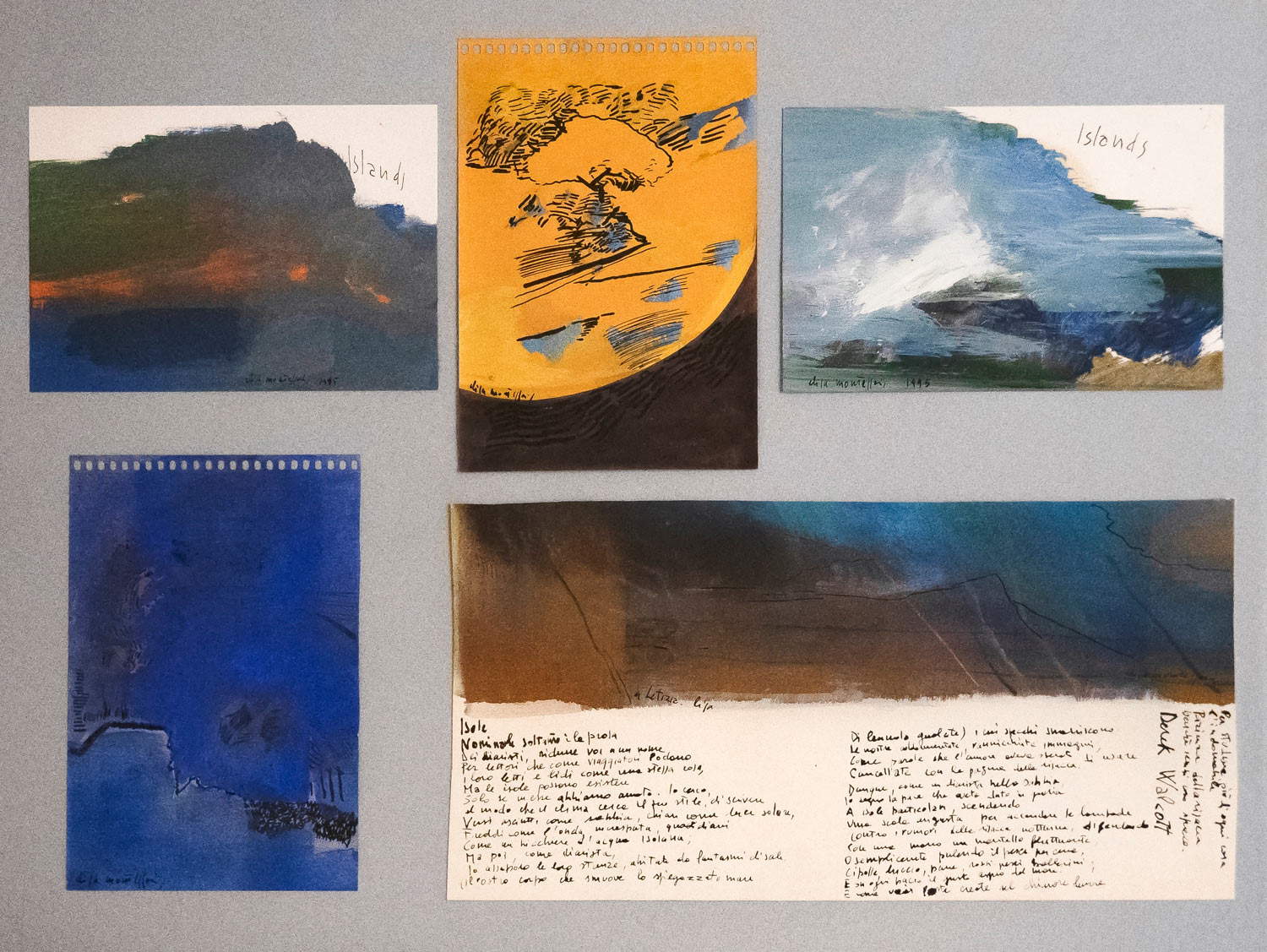

The theme of Souls is represented by Edoardo Tresoldi’s Sacral (2016), a large piece of architecture located in the museum’s 16th-century cloister that aims to ideally reinterpret the Noble Castle or Castle of the Magni Spirits that Dante mentions in the fourth canto of the Inferno. One of the leading exponents of Land Art, Richard Long, reinterprets the theme of the Journey through the installation Trastevere Spring Circle (2012), while Female Figures are represented in the works of Letizia Battaglia, Tomaso Binga, Irma Blank, Rä di Martino, Maria Adele Del Vecchio, Giosetta Fioroni, Elisa Montessori, Antonia Pozzi and Kiki Smith. Reinterpreting the theme of Dream are the works of Robert Rauschenberg, among the leading exponents of American pop art, with the thirty-four illustrations for Dante’s Inferno (1958-1960), and Adelaide Cioni with the site-specific installation Cinque pezzi di cielo (2021) and Il sole (2019). Finally, Light is represented by Gilberto Zorio’s sculpture Stella-acidi (1982).

A POP Epic is thus a major exhibition on Dante’s popular fortune, his images, and his work.

For more info you can visit www.mar.ra.it

Image: Teodoro Wolf Ferrari, Affiche Olivetti M1 (1912; poster on paper, 32.6 x 21.8 cm)

|

| Dante is Pop. At the Ravenna Mar, the popular fortunes of Dante from the 14th century to the present. |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.