This is the third stage for the Terre degli Uffizi project, the palimpsest of exhibitions that the Uffizi Galleries are producing together with Fondazione CR Firenze in museums in Tuscany as part of their respective Uffizi Diffusi and Piccoli Grandi Musei programs. The exhibition is scheduled at the Museum of the Battle of Anghiari from August 31, 2021, to January 6, 2022, and is entitled The Civilization of Arms and the Courts of the Renaissance: the exhibition, promoted by the Municipality of Anghiari, aims to recount a particular process that affected the village of Anghiari during the Renaissance: the transformation of a part of the local notables from warriors, fighters and men-at-arms into erudite and culture-loving courtiers. A phenomenon found throughout Italy, but particularly evident in the center of the upper Tiber Valley.

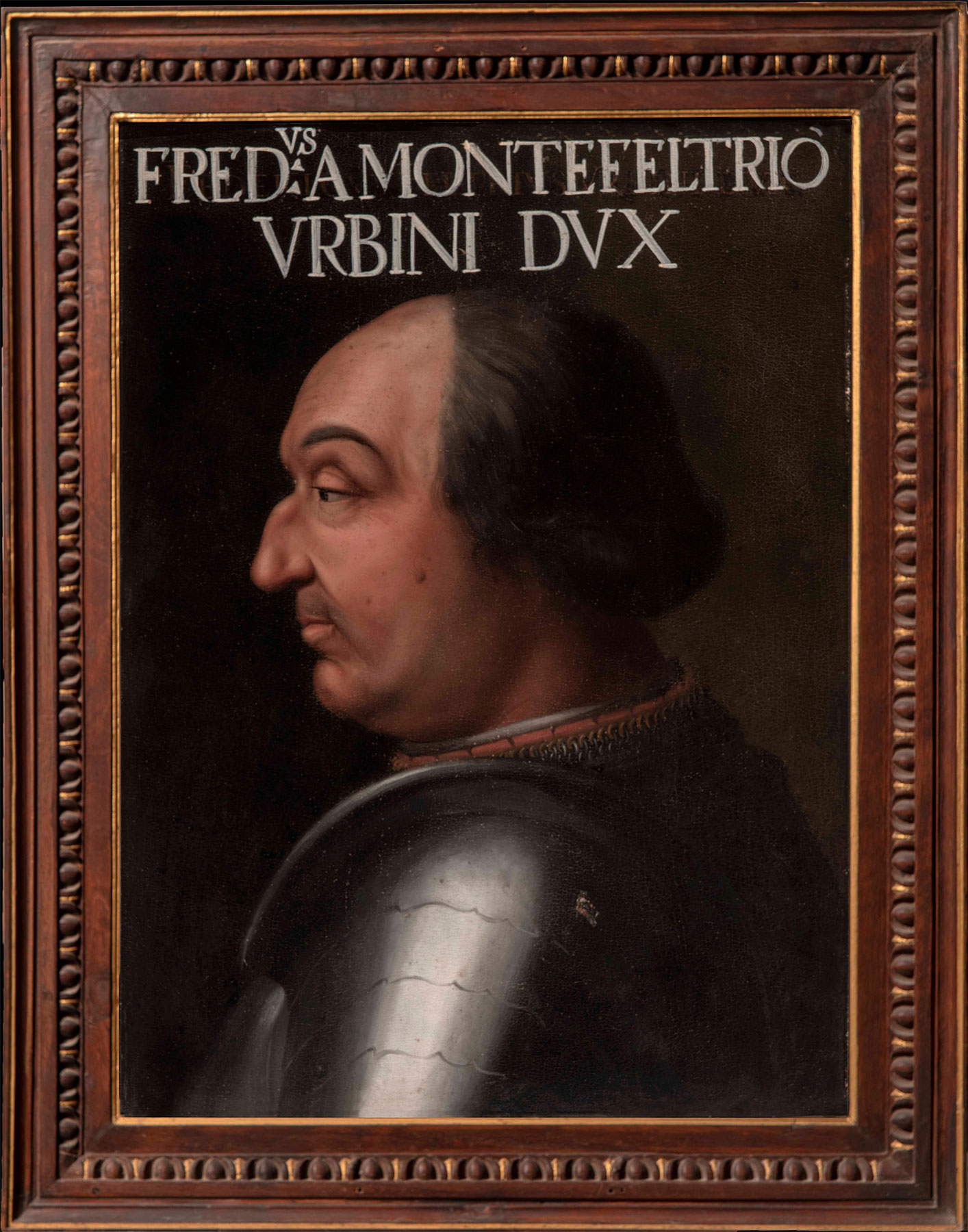

The subtitle of the exhibition, Federico da Montefeltro at Anghiari, is intended to account for some recent historical studies on the families of the village: indeed, friendships and kinship ties with some of the major houses of the time, and in particular with the Montefeltros of Urbino, have emerged. Federico da Montefeltro himself (Gubbio, 1422 - Ferrara, 1482), who is the protagonist of the exhibition with his posthumous portrait executed by Cristofano dell’Altissimo (Florence, 1525 - 1605) for the Jovian series, was in Anghiari at least twice, in 1468 and 1474, according to documents. The portrait of Federico da Montefeltro, around which the exhibition’s coordinated image was also built, more than a century after Piero della Francesca’s portraits of the dukes of Urbino, now housed in the Uffizi, still drew on that illustrious precedent. The selection of works on display, including painted tabernacles, portraits, weapons and battle scenes, partly from the Uffizi’s storerooms and partly from collections in the area, aims to delve into the lives of the men-at-arms of the time. The exhibition also finds a connection with the territory for another well-known reason: here, in fact, on June 29, 1440, the decisive battle was fought between the Milanese troops of the Visconti and the coalition led by the Florentine Republic, allied with Venice and the Papal States, which won against Milan. It was precisely this battle that Leonardo da Vinci, between 1504 and 1505, was called upon to re-enact in the Salone dei Cinquecento of the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. The Florentine victory was extremely relevant to the fate of Italy at the time and also marked the destiny of Anghiari, deeply conditioning its social fabric.

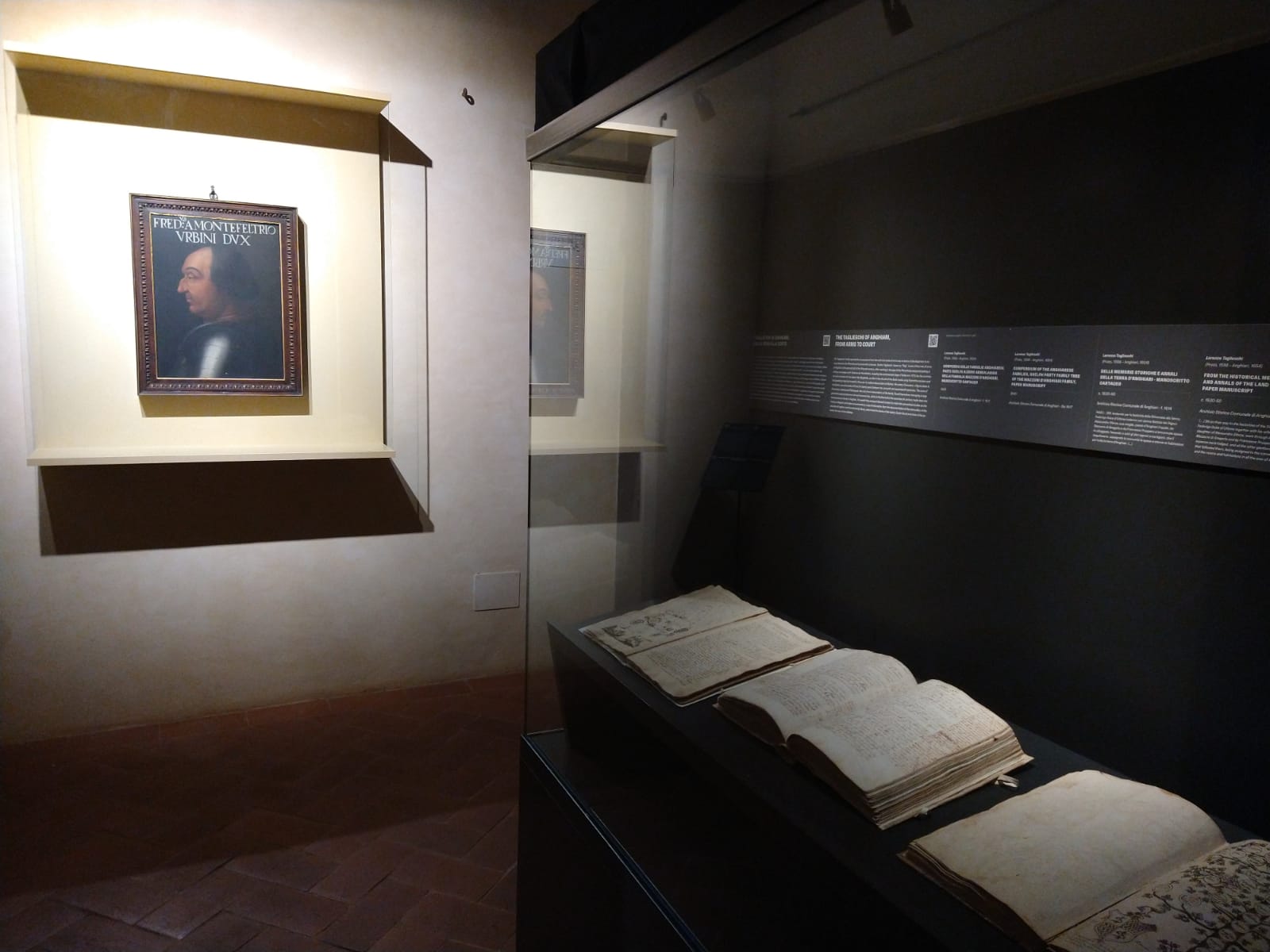

|

| Hall of the exhibition The Civilization of Arms and the Courts of the Renaissance. Photo by Stefano Casati |

|

| Hall of the exhibition The Civilization of Arms and the Courts of the Renaissance. Photo by Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Hall of the exhibition The Civilization of Arms and the Courts of the Renaissance. Photo by Finestre Sull’Arte |

In the period studied by The Civilization of Arms and the Courts of the Renaissance, which runs from the mid-15th century to the following century, the town of Anghiari supplied men-at-arms to various armies of Italian lordships, whose nobility was often related to that of the Tuscan town: a solid and enduring military tradition thus developed, and many of the town’s families (beginning with the Taglieschi, the Mazzoni and the Giusti) had among their members some well-known warriors of the time, all of whom came from the highest social classes and were later able to nurture strong cultural interests and even to become supporters of the arts in some cases. The exhibition focuses on these historical figures associated with Anghiari, who from knights and soldiers became, as mentioned, courtiers. Archival research has revealed the presence, in fifty years at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, of as many as 24 men-at-arms, but there were probably many more because research has not been exhaustive. And in that period Anghiari took on the form in which we see it today.

“The title of the exhibition is actually not an occasion title,” explained Professor Francesco Storti of the University of Naples Federico II, “but it is the result of a major historiographical revision. This civilization has always been considered as that of mercenaries, of a corporativist category, but in reality this is not true: it is instead a segment of Italian society, also quite substantial, that made an important cultural contribution.” In January 2020, a conference on these issues was held in Anghiari, entitled Anti-rhetorical Battles. Rereadings of the Mercenary Role in Renaissance Italy, in which the scholars who attended pointed out the need to revisit a certain rhetoric about Italian Renaissance weapons before the Italian Wars, relating to so-called bloodless battles and certain games or amusements that mercenaries would enact as opposed to bloody, murderous warfare: in fact, the condottieri, Storti says, “were perfectly capable of murderous warfare. The point is that they did not want to make it: therefore, just as in the Renaissance there is a civilization of politics and political language and a civilization of the arts of artistic language, in the same way there is a civilization of weapons, which is pervasive and present at the cetual level in all Italian cities, in Anghiari as in Capua, in Lombardy as in Cosenza, everywhere. It is also a culturally substantial class: from the great prince and the great condottiere lord down to the last man-at-arms, they all knew how to write, they knew how to make war (and they did it very well), and they were able to make a contribution to the cultural growth and to the idea that Italian society had of itself, because that is what the Renaissance is all about: it is the moment when one acquires self-awareness and thinks that this self-awareness as a category and as an individual can be mixed together with that of others through a dialogue.”

One of the goals of the review is that from the halls of the Museum of the Battle of Anghiari a historiographical revision can begin, Storti said, “Federico da Montefeltro, a great condottiere lord, is not simply the patron who makes war, pockets the money and then finances the works of art. Federico is the representative of a class that believes in art, believes in what it does, and wants to make war in a different way. Let us therefore make a contribution starting from Anghiari, which is only apparently a small town. It is from a geographical point of view, but from an intellectual and cultural point of view it is not: from here a new discourse on a very substantial part of Italian Renaissance culture can begin.”

|

| The Museum of the Battle of Anghiari. Photo by Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| View of Anghiari. Photo by Stefano Casati |

The exhibition opens with a Virgin and Child, St. John and Angels by Pseudo Pier Francesco Fiorentino from the second half of the 15th century and a coeval Madonna and Child by Lorenzo di Giovanni di Nofri, known as the “Master of San Miniato,” from the same period: the two tabernacles, on loan from the Uffizi, are meant to offer two examples of the typical production that was supported by Anghiarian men-at-arms (although these two works do not refer to the Anghiari territory: the vast majority of what these warriors financed in the arts has in fact been lost). Alongside the workshops of the greatest and most celebrated masters there were other workshops that imitated or reused the forms of the former, managing to secure a considerable slice of the market, aimed above all at the small and middle classes: this is the sphere in which the two tabernacles that open the exhibition originate. Devotional works of this kind, as well as more demanding commissions, can be found mentioned in documents concerning Anghiarese men-at-arms: for them, the social need to gain prestige through art was thus commensurate with the finances of the patron, who could grab a valuable work for domestic use or for dedicatory altars in religious buildings. Among the works of which we have news: Giusto Giusti commissioned Giovanni di Francesco del Cervelliera to paint a panel with St. Nicholas the Bishop; Matteo Taglieschi had an altar with St. Mary the Virgin and St. Matthew carved by the stone mason Santi da Settignano; Gregorio di Vanni had a painting done by the unknown Florentine “Greek-style” painter Piero di Lorenzo. These works have disappeared, but these reports testify to the cultural fervor of those men-at-arms.

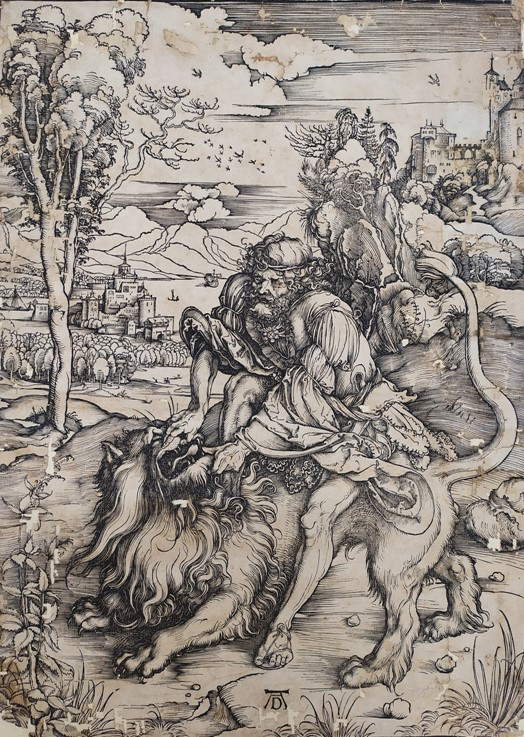

The cultural interests of the Renaissance men-at-arms are also evidenced by two woodcuts by Albrecht Dürer (Nuremberg, 1471 - 1528), owned by the Museum of the Battle of Anghiari: in the late 15th century there were indeed many opportunities to own a valuable work of art, and printed engravings were a particularly effective medium. Dürer’s works, which had in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries a great diffusion and penetration in society, are an example of this. The many attestations of Dürer’s works in prestigious collections of important Florentine families, including the Doni, suggest a very widespread diffusion of these folios.

We then come to the presence of the portrait of Federico da Montefeltro executed by Cristofano dell’Altissimo around 1556 as a copy of the painting found in Paolo Giovio’s celebrated Musaeum. As anticipated, interesting links were discovered between Federico da Montefeltro and Anghiari: the condottiero was in the village the first time in September 1468 and the second time on July 5, 1474. The most significant presence seems to be in 1468, when the duke of Urbino, with his second wife Battista Sforza and court, was the guest of Mazzone di Gregorio and Francesco Prospero, two Anghiarian men-at-arms who had both fought with Federico da Montefeltro. Mazzone’s father, Gregorio, who had participated with Federico in the taking of Piombino in 1448, had passed away just in September 1468. We do not know if this death was the reason for Federico da Montefeltro’s visit to Anghiari, but it is nevertheless considered very significant news. Still, the presence of Anghiarian companies under Federico’s command at thesiege of Volterra in 1472, the military action ordered by Lorenzo the Magnificent following a dispute between Florence and Volterra that arose out of a quarrel over the exploitation of a mine, turns out to be important. With the Duke of Urbino were at least three Anghiarian companies: that of Matteo Taglieschi, that of Anghiarino, and a company of Iacopo Giusti (the latter son of Giusto Giusti, the notable of Anghiari close to Cosimo the Elder de’ Medici). The town was won to the pacts but the inhabitants were driven to obedience by the violence of the soldiers who sacked it. In 1473, when hostilities ended, Iacopo Giusti was appointed castellan of Volterra with high compensation: 150 gold florins a year. The following year Federico passed through Anghiari on his return to Urbino. A further focus is devoted to the Taglieschi family: indeed, it is an example of how the craft of arms was a means for the development of society between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries. Matteo Taglieschi, known as “dog,” was one of Anghiari’s most prominent men-at-arms in the second half of the fifteenth century, often working in the pay of the Florentines and participating in military campaigns with Federico da Montefeltro, but he commissioned for his town a palace in the Borghetto, an altar in the Badia church made with Florentine labor, and had jewelry made for himself in Florence.

In the last room, a special section is devoted to the figure of the “man of arms and courtier”: indeed, the military life of the 15th century developed a class of warriors capable of forming a dynamic milieu linked by common interests, and in which the “change of flag” was often agreed upon and fired by the patron, who could be a state, a lordship. This way of understanding the craft of arms was considered already inconceivable to the chroniclers of the seventeenth century, but accepted as that was the custom of the times (though still there was no shortage of loyal condottieri, even in Anghiari). The figure of the Italian condottiero fell into decline in the first decades of the sixteenth century and particularly in the aftermath of the sack of Rome in 1527: Italian warriors, with the advance of increasingly centralized, dynastic and organized political interests, were deemed unreliable and very expensive. Their figure, therefore, was transformed: the man-at-arms became a courtier, rightfully becoming part of the power system and increasing his prestige through participation in court activities. The transformation has taken place; social success is achieved. Testifying to the transformation is a portrait of Man in Armor by an unknown French painter (in the past it was given to Bronzino), who is presented in rich, ornate, and elaborate armor: it is precisely this armor, so rich and complex, together with the character’s bearing, that introduces the theme of the transformation of the figure of the fifteenth-century man-at-arms into a man of the court.

The last section is devoted to the battle between knights: the Battle of Anghiari in 1440 is evoked by an engraving by the Flemish Gérard Edelinck (Antwerp, 1640 - Paris, 1707) that reproduces the Struggle for the Standard that Leonardo da Vinci was supposed to have frescoed in the Salone dei Cinquecento in Florence, and which provided probably more than one cue to the French painter Jacques Courtois (Saint Hyppolite, 1621 - Rome, 1676), Italianized as Giacomo Cortese, an ex-military man and painter who became one of the specialists of battle scenes in the mid-seventeenth century. On display is one of his Battaglia di Cavalleria (considered by some to be a school work, however), where the soldiers’ dismay during the war action is vivid.

|

| Pseudo Pier Francesco Fiorentino, Virgin and Child, St. John and Angels (1459; tempera on panel, 84 x 64.5 cm, framed 156 x 104.5 cm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries) |

|

| Lorenzo di Giovanni di Nofri known as Maestro di San Miniato, Madonna and Child (post 1466; tempera on panel, carved, gilded, and painted frame, 42.5 x 30 cm, with frame 70 x 48.5 cm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries) |

|

| Albrecht Dürer, Samson Slaying the Lion (1497-1498; woodcut, 380 x 278 mm; Anghiari, Museo della Battaglia) |

|

| Unknown painter (French scope), Man in armor (second half of the 16th century; oil on panel, 76 x 89 cm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries) |

|

| Gérard Edelinck, Struggle of Knights from Leonardo da Vinci’s Battle of Anghiari (1657-1666; burin engraving, 606 x 450 mm; Anghiari, Museo della Battaglia) |

|

| Jacques Courtois known as Borgognonge, Battle of Knights (second half of the 17th century; oil on canvas, 174 x 233 cm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries) |

“It is a great satisfaction,” said Anghiari Mayor Alessandro Polcri, "that Anghiari is among the top five projects of the Terre degli Uffizi initiative, including three in the province of Arezzo. A collaboration with the Uffizi Galleries born in 2019 on the occasion of the five-hundredth anniversary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci and now thanks to important historical information from archival sources linking the history of Anghiari to that of the greatest Renaissance courts. A relationship between city and periphery in the Renaissance that is now fulfilled in this important collaboration with the Uffizi Galleries and which also sees the collaboration with the University of Naples Federico II continuing. Special thanks to all the staff of the Uffizi Galleries, especially director Eike Schmidt, to the Fondazione CR Firenze and especially to our municipal museum, the Museo Battaglia Anghiari, without which it would not have been possible to realize all this."

“The Anghiari exhibition,” says Uffizi Galleries director Eike Schmidt, “is an opportunity to value scientific research, which continues to bear fruit and produce discoveries even on well-known themes and periods. And it is an extraordinary opportunity to discover the social and cultural fabric of Renaissance Italy, where fierce condottieri such as Federico da Montefeltro could return home after their bloody campaigns and take on the role of the enlightened humanist, cultivate literary and philosophical studies, commission sublime works of art, while at the same time establishing through arts and letters another form of (virtuous) competition with the lords of other states. War and Peace are admirably intertwined in the Anghiarian initiative: in the portraits and works on display, characters linked to the Valtiberina come to life, with their military aspirations and intellectual interests that forever forged the character of this solemn and splendid territory.”

“This exhibition,” recalled the president of the Fondazione CR Firenze, Luigi Salvadori, "represents for the Fondazione CR Firenze a bit of an emblem of the Terre degli Uffizi project and confirms the goodness and value that inspired it. In fact, thanks to our institution, in August 2014, the famous Tavola Doria depicting the epic victory in 1440 of the Florentine troops over the Milanese ones was exhibited for the first time in this city. The historic occasion was offered by the exhibition Capolavori in Valtiberina. From Piero della Francesca to Burri, which was part of the 10-year cultural marketing program called Piccoli Grandi Musei that our Foundation launched in 2005 and which is among the ’fathers’ of Terre degli Uffizi. This project had precisely the purpose of enhancing and publicizing the lesser-known beauties of our land and their specific identities. On that occasion the Foundation made an important investment not only by organizing various events in the area but also by financing the climate-controlled shrine protecting the Tavola Doria. That is why we are pleased to be able to return today to Anghiari with a cultural proposal that develops and amplifies these intentions and that we are promoting together with Italy’s most important museum. Terre degli Uffizi therefore comes at the right time for its message to be fully received and appreciated. This is confirmed by the success of the two exhibitions that are part of the five stages of Terre degli Uffizi: In the Sign of Dante at the Poppi Castle, which closes on Nov. 30, and Dante and Andrea del Castagno in San Godenzo, which has just concluded at the Visitor Center of the Casentino Forest Park."

“The role of the Anghiari Museum in all this,” stressed Gabriele Mazzi, director of the Museum of the Battle of Anghiari, “is as a simple collector of pieces. We have the pieces of the history of this village, but they are pieces of history that are not only local. Obviously we have today a sometimes somewhat strange perception of the Italian province, and so there is also a tendency to underestimate the roles that territories have played in shaping history, civilization and what we are today. But Anghiari in this case is a small example.”

|

| Warriors and cultured patrons: an exhibition on Renaissance men-at-arms in Anghiari |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.