From November 26, 2022 to May 14, 2023, the MIC - International Museum of Ceramics in Faenza presents a major exhibition dedicated to the ceramics of Galileo Chini. Entitled Galileo Chini. Ceramicsbetween Art Nouveau and Deco, the exhibition, curated by Claudia Casali and Valerio Terraroli, displays about two hundred pieces, most of them previously unpublished, for a journey through Chini’s ceramics from 1896 to 1925. What are the highlights of the exhibition? What is Chini’s relationship with ceramics and with Faenza? What is the difference between Art Nouveau and Deco? We talked about all these topics with curator Valerio Terraroli. The interview is by Ilaria Baratta.

IB. Why did the International Museum of Ceramics in Faenza decide to dedicate an exhibition to Galileo Chini?

VT. First of all because Galileo Chini is one of the great masters of ceramics of the first half of the 20th century, and secondly because 2023 will mark the centenary of the inauguration of the Terme Berzieri in Salsomaggiore Terme, in the province of Parma: the last great ideational, decorative and ceramic masterpiece of Galileo Chini and the Manifattura Fornaci S. Lorenzo of the Chini family. The exhibition will close on May 14, 2023, then passing the baton to the City of Salsomaggiore Terme for celebrations in honor of the artist with an exhibition and a series of initiatives

What did the relationship between Galileo Chini and Faenza consist of?

It is a very close relationship because Faenza is one of the world capitals of ceramics tout court and of majolica in particular. Chini also participated in 1908 in decorating the panels that adorned the artistic sections of the exhibition dedicated to Evangelista Torricelli, an exhibition from which the idea of establishing an international museum of modern ceramics was born. Of this museum, namely the MIC in Faenza, Galileo Chini was among the first donors of works.

What goals have been set for this exhibition? Is it suitable for everyone or mainly for an audience of enthusiasts and connoisseurs?

Like the MIC itself, the exhibition on Chini the ceramist also wants to speak to the widest possible audience: the exhibition is really designed for a wide audience and is not aimed only at specialists. It is an exhibition that is a pleasure for the eyes, it is curious, it is fun, according to my point of view. Obviously a collector, a specialist, a ceramist, an artist will be able to find in it, cues and solicitations, but for the audience of non-specialists the exhibition is interesting and, at the same time, enjoyable because the objects exhibited are very different from each other and then they tell the story of a young man, because Galileo Chini was just twenty-three years old when he decided with three other friends to start a small business (L’Arte della Ceramica in Florence in 1896) and later in Mugello with his cousins he opened the Fornaci S. Lorenzo, carrying on that industrial initiative until the years 1925-1926. The exhibition, which features some 300 pieces on display including ceramics and drawings, is thus also the story of a young artist who put himself on the line and faced the problems of his time, namely how to respond to the solicitations of modernity, how to interpret the Art Nouveau taste and, later, the Déco taste.

Galileo Chini,

Galileo Chini,

How is the exhibition structured?

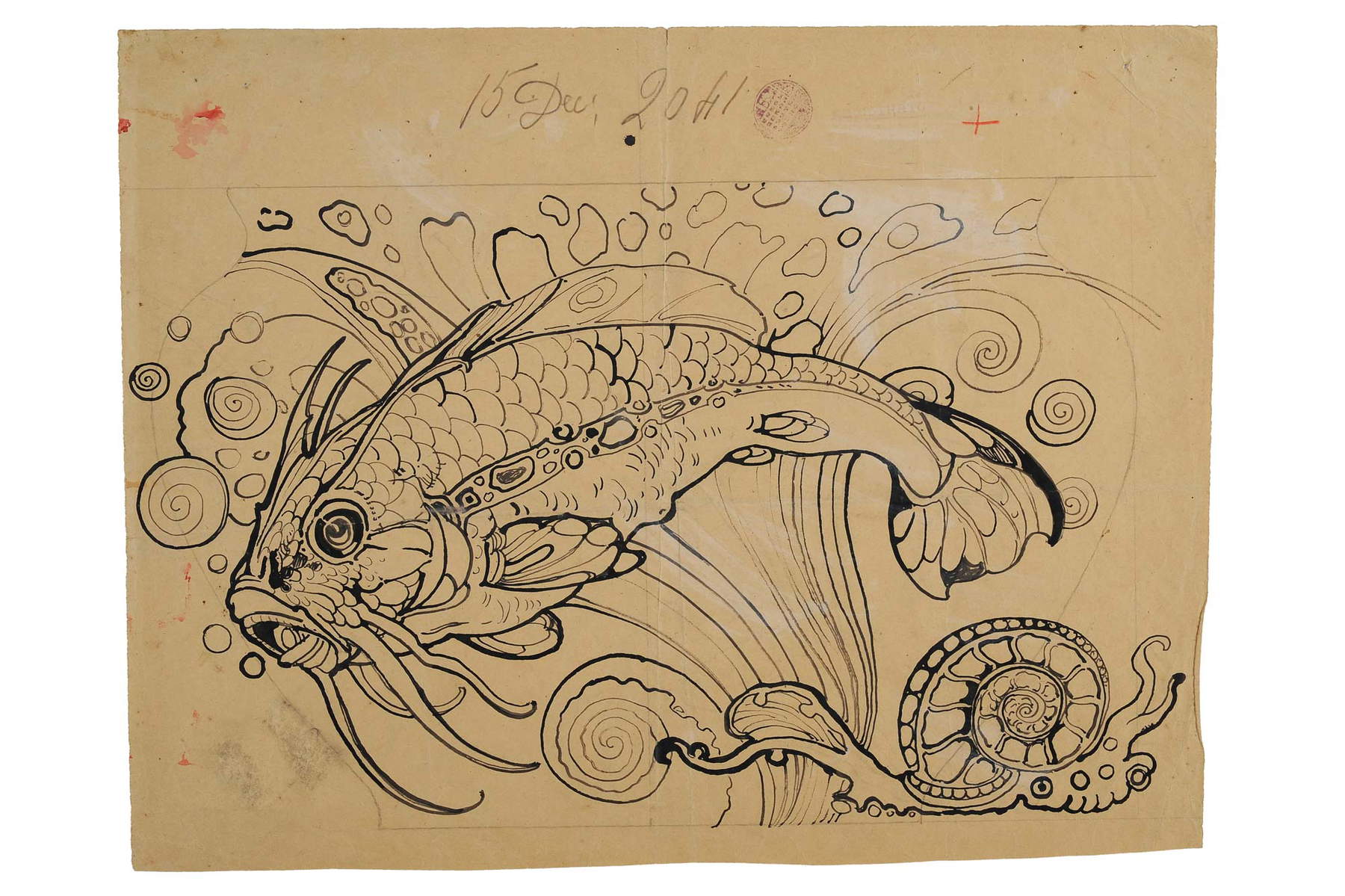

It is basically structured according to the time line, but as curator, together with Claudia Casali, we did not think of a philological, specialist type of exhibition, but we still followed a historical development. The exhibition opens with the adventure of L’Arte della Ceramica, from 1896, bringing out the characters of the themes dealt with by the new taste that Chini was bringing forth, namely French-style Art Nouveau and then Italian Liberty, and we continued along this line, arriving at the interest in Klimt and the Secession, all the way to Déco with Terme Berzieri. However, along the way, there are also sections devoted to specific themes, such as the depiction of the peacock, which is a theme that Chini continued to deal with from the beginning until the 1920s (the peacock is a symbol of international Art Nouveau). Another recurring theme is aquatic fauna, including fish, salamanders, and starfish, which characterize Galileo’s work as a decorator at spa towns (Montecatini, Porretta, Salsomaggiore, and Castrocaro). And then a particular technique is presented, that of stoneware: a fairly crude ceramic material that was used to create industrial objects, but which the Chinis were able to transform into an artistic object, where the material, light brown/beige/gray in color ,is decorated with very simple shapes, some even geometric, giving rise to very modern objects.

By what is an Art Nouveau ceramic characterized from one of Art Deco taste?

The Art Nouveau style is related to floral: its inspirational motifs are nature, especially plants, flowers, water plants, wisteria, lilies, iris, and the female figure, young with floating hair, representing the new age, the eternal spring (the distant inspiration is Botticelli’s Venus ). The Déco taste identifies itself because it is symmetrical, more geometric, more precious, and more monumental than Art Nouveau and, therefore, presents itself as an alternative to the stylistic grammar of Art Nouveau; for as much Art Nouveau and Art Nouveau are naturalistic, enveloping, and asymmetrical as Déco is regular and geometric.

Where do the three hundred or so pieces on display come from?

Almost all of the pieces come from private collections, except for four that belong to the collection of the MIC in Faenza (entered over time through donations from the Chini family) and one comes from the Chini Museum in Borgo San Lorenzo in Mugello. So the exhibition also has the task of bringing out many pieces that people don’t know about because they are never seen.

So what are the pieces that one should definitely dwell on?

Definitely the first one you see as you enter the exhibition: an amphora of Renaissance taste, which therefore makes it clear how Galileo Chini starts from the great tradition of Tuscan Renaissance ceramics, but which presents on the surface of the vase young people, such as woodland nymphs, and fauns and even a centaur and a centaury embracing, symbolizing the eternal renewal of love in spring, thus an Art Nouveau theme. Then continuing on, corresponding to the great Turin exhibition of 1902, one encounters lustre-decorated ceramics with floral but more Klimtian themes, close to Northern European taste; I then find the peacock area very amusing. I would stop to see the stonewares and last the ceramics with monstrous fish and sea creatures, ending with Terme Berzieri, because the last section is dedicated to the large three-meter by three-meter cardboard that constitutes the final design of the decorations that Galileo painted on the walls of the building’s interior staircase.

Galileo Chini,

Galileo Chini,

There are also unpublished works among the ceramics. How many are there and what do they depict?

There are unpublished pieces, as a percentage they will be 30 percent of the total. Others over time have been published and made known. Many unpublished ones, however, are in the drawings: there are quite a few, of which many have never been seen. In the tour, the visitor is continually given the opportunity to compare the preparatory drawing with the piece, in fact understanding how the ideas for the different ceramics came about. Galileo did not model the pieces, he invented invented the shapes, from which the molds, designs and decorations were then made, then the pieces were created using the molds and were decorated pictorially by workers who knew how to paint along the lines of Galileo’s design. So what is enhanced in the exhibition is not only the final object, but the whole creative and then executive process that leads to the art piece.

So from the preparatory drawings we also understand Galileo Chini’s creative process.

Correct. Very significant in this sense is a large plate with a seabed, already from the 1920s, displayed with Galileo’s drawing next to it with all the indications (including the colors and their position). One can then see a polish all pitted which was kept in the factory, together with the drawing, and then on occasion placed on the ceramic plate to be painted and dusted with charcoal powder, which left thin traces of the drawing, and then the decorators would superimpose the color palette on it with glaze or luster following the artist’s instructions. The piece was then fired a second time to fix the color and give it the glazed appearance, typical of majolica, or the lustre effect.

In your opinion, is Galileo Chini a fairly well-known artist to the general public today?

Although exhibitions have also been dedicated to him recently, but they dealt with his entire production, unlike the one at the MIC in Faenza, which focuses on the period 1896-1925 and on Galileo Chini only exclusively inventing ceramics, the general public may not know him: it is a name that probably immediately evokes works, but you would only have to go to the Venice Biennale, right at the entrance to the central Pavilion of the Giardini, and look up at the dome: it was all painted by Galileo Chini in 1909.

In conclusion, once you have visited the exhibition, where do you suggest going to discover the art of Galileo Chini?

Once you have visited the exhibition, just go up to the second floor of the museum: there is a whole showcase here with pieces by Galileo Chini that were not displayed in the exhibition on purpose so that the public could go and see the museum as well, but they are related to his contemporaries and other artists who worked with ceramics in the 1910s and 1920s. Then I would recommend going to Salsomaggiore Terme to see the Berzieri Baths, which today can be seen from the outside because it is a construction site (hopefully by May they will be open). And finally, also in Salsomaggiore, is the Grand Hotel, whose ballroom was entirely painted by Galileo Chini with oriental themes related to his trip to Siam (1911-1913) to decorate the Throne Palace and to his experience as a set designer for the staging of Giacomo Puccini’s Turandot (1926). Then again, you can go to Montecatini Terme, because all the ceramics and all the decorations of the famous Tettuccio Baths are by Galileo Chini.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.