In recent days, several scholars have been very vocal about the possible Caravaggesque autography of an Ecce Homo that was about to go to auction in Madrid at the Ansorena house. However, there are also those who maintain a much more cautious stance: this is the case of Professor Antonio Vannugli, a professor of modern art history at the University of Eastern Piedmont and a scholar of seventeenth-century art, who has worked extensively on the collection of Juan de Lezcano, indicated these days as the possible provenance of the resurfaced painting. We heard from him to get his opinion on the painting. The interview is by Federico Giannini.

|

| Caravaggio (attr.), Ecce Homo (oil on canvas, 111 x 86 cm) |

FG. Professor Vannugli, what is your opinion on theEcce Homo in Madrid?

AV. Assuming that the fact that the painting popped up like a mushroom is true (we know nothing about where it came from: we only know that it was in Madrid for a decade or so), it is a completely decontextualized painting. I have not seen it from life as many of us have, yet I have strong doubts that it is by Caravaggio, and if it is by Caravaggio I am very reluctant to accept it as a work from the Roman period. Let’s say there is a double level of resistance. First of all, perplexity about the attribution, and in the case of Caravaggio the ability to come to a shared opinion is very difficult, especially when it comes to paintings that do not have a very definite pedigree. Then, on top of that, this is a virtually unknown composition, in the sense that there is only a copy of which we do not know the location and measurements (but whose framing is almost identical to that of the Madrid painting) that was published by Longhi in 1954 and was located somewhere in Sicily seventy years ago. However, assuming that a good degree of consensus is eventually reached, I am very reluctant to see it as a Roman work, because Caravaggio’s last Roman works such as the Death of the Virgin, the Madonna of the Palafrenieri, and the St. John the Baptist in Kansas City seem to me sincerely quite different.

Some have linked the painting to a possible Massimi commission, while others have already discarded this hypothesis. Could this be a viable avenue?

Let me preface this by saying that, in my opinion, a particular phenomenon has been taking place for many years (which also concerns, for example, Leonardo da Vinci, just to mention another name), which is that when it comes to names of this caliber we settle for hypothetical levels much lower than those demanded for any work of art of not as striking importance to the mass media. I want to say that if instead of Caravaggio we were talking about Giacinto Gimignani or Bartolomeo Manfredi, the papers in our hands would induce far greater caution, we would all be on the “maybe” side, whereas in the case of Caravaggio it seems that it is enough to establish proveniential family trees that are based on dubious assumptions. But let’s cut to the chase: we have a nice deck of cards. We have an autograph receipt from Caravaggio dated June 1605 in which the artist undertook to paint for Massimo Massimi a “picture” of unspecified theme intended to accompany, even in size, aCoronation of Thorns that he had previously painted for him. So we have a receipt from Ludovico Cardi known as Cigoli in which the artist states, without indicating the subjects, that he was going to paint a “large” painting that was to pair with an already existing painting by Caravaggio: this is a receipt from 1607, by which time Caravaggio had already left Rome a year before. From Cigoli’s biography, written some 20 years later by his nephew Giovan Battista Cardi, we then know with certainty that the paintings painted for Massimi by him and Caravaggio both depicted an Ecce Homo, as did a third executed for the same client by another artist, Passignano. The fourth item is a preparatory drawing by Cigoli now in the Louvre for his Ecce Homo, on a sheet where at the bottom there is also a sketch of the composition of aCoronation of Thorns. Now the dimensions of Cigoli’s EcceHomo, which was sold by Massimi as early as the 1720s and is now in Florence at the Pitti Palace, and the composition of this Coronation of Thorns sketched by Cigoli under the preparatory study for his own Ecce Homo correspond precisely to Caravaggio’sCoronation of Thorns of Prato. So, the fact that the Prato painting is the Caravaggio painting painted for Massimi is confirmed by the identity of measurements with Cigoli’sEcce Homo and the compositional correspondence with the sketch under Cigoli’s drawing. At this point, however, we have the problem of Caravaggio’sEcce Homo; it should have the same measurements as the other two. Let’s move on to 1644: in the inventory drawn up upon Massimo Massimi’s death, aCoronation of Thorns and an Ecce Homo appear inside his room, both cited as “large paintings” and both protected by an identical red taffeta curtain to emphasize their preciousness, in terms that make them think of the same dimensions. This is not enough: an Ecce Homo appears again, in the same setting, in a 1696 inventory of the Massimi house. By contrast, in the life of Caravaggio published in 1672 Bellori states that his Ecce Homo “was taken to Spain,” news that seems to go along with the lesser appreciation the painting got compared to Cigoli’s, which was nevertheless alienated in his lifetime by the commissioner. Thus a Y opens: on the one hand Bellori’s testimony, on the other the 1644 inventory. If at this point we call into question the two different Ecce Homo attributed to Caravaggio that have come down to us, we have to admit that any hypothesis of identification assumes that Caravaggio did not comply with the measurements and did not make it equal to theCoronation of spinec aspromised, when in fact Cigoli was faithful to the requests; in fact, both Prato’sCoronation of Thorns and Cigoli’sEcce H omo measure 178 cm in height, while Genoa’sEcce Homo is only 128 cm and Madrid’s just 111. Or we should assume that Caravaggio’s painting was cut down, because today the measurements do not match. And again in the Massimi inventory the two paintings are without an author’s name: if it were a painting of a very rare subject the identification might gain value, but we are talking about an Ecce Homo, a typical image of private devotion, there were plenty of them at the time. Then it is also a critical question: it is a matter of putting the Massimi inventory on one plate of the scales and Bellori’s testimony, preceded by the more vague testimony of Cigoli’s nephew, on the other. So if we accept as valid the testimony of the inventory, I am surprised, because I think about the fact that in the inventory there are not even names, and how do we not infer, for example, that Massimo Massimi could have remained in possession of a copy? Massimi could not have made himself another Ecce Homo, so much so that as we have seen Cigoli’s nephew says that he had an Ecce Homo painted by Passignano as well, and it is a painting that we know nothing about. How can we rule out that the inventory does not refer to the painting by Passignano, which moreover could have been an equally beautiful painting? But let us still try to take the albeit anonymous report of the inventory at face value, and make it go along with the testimony of Cigoli’s nephew (an oral testimony, received from his uncle), which, it is true, does not explicitly say that Caravaggio’sEcce Homo was sold (Baldinucci inferred this at the end of the seventeenth century, interpreting Giovan Battista Cardi’s account). We would be forced to argue that Caravaggio’s painting (if we are to at least listen to Bellori) would have been taken to Spain after Massimo Massimi’s death, after 1644. So either the painting was gone between 1644 and 1672, when Bellori published his biography of Caravaggio (which, moreover, was written a few years earlier), with good regard to the later inventory of 1696, or we would have to disprove Bellori as well, and the argument begins to get very heavy. But even in the other case, a painting leaving Rome between 1644 and the 1660s, among literary sources, travelers, and various testimonies should have produced some trace, because after 1644 a Caravaggio painting going around and changing hands is already making headlines.

|

| Caravaggio, Coronation of Thorns (1602; oil on canvas, 125 x 178 cm; Intesa San Paolo Collection, exhibited in Prato, Palazzo degli Alberti) |

|

| Ludovico Cardi known as Cigoli, Ecce Homo (1607; oil on canvas, 175 x 135 cm; Florence, Palazzo Pitti, inv. 1912 no. 90) |

We must therefore follow the path of Spain. Many people these days have mentioned a possible provenance from the collection of Juan de Lezcano, which you know very well. Are we facing a viable possibility?

First, let us recall that in Juan de Lezcano’s inventory, compiled in Naples in 1631, an Ecce Homo by Caravaggio appears very prominently, and let us consider that if a painting by Caravaggio came out of Rome in 1616, that is, at the time when Lezcano was ending his stay in Rome as secretary to Ambassador Francisco de Castro, it is more possible that it left no trace. Therefore, if we accept the idea that theEcce Homo in the 1644 Massimi inventory is not that of Caravaggio and listen to Bellori, and also to Cigoli’s nephew according to Baldinucci’s interpretation, certainly the hypothesis of an identification of the Massimi painting with the Lezcano painting is very plausible, because Lezcano was in Rome from 1609 to 1616, then left. So it would be an eventuality that would fit perfectly into the story. Lezcano, in his inventory, says that the painting is worth more than 800 ducats. Also on measurements Lezcano is very approximate: for him a “large painting” is any painting that is not a Flemish cabinet picture, so a “large painting” for him is also a painting of only four to four and a half Roman palms, that is, of about one meter (a measurement that to Lezcano is already enough to define a “large” painting, we know this in relation to the various paintings of Orazio Borgianni of whom he was a friend and which he describes in a row at the beginning of the inventory). Then Lezcano is very sloppy from the point of view of iconography (but at least onEcce Homo we can avoid going to syndicate), however, he is very careful from the point of view of economic value and attribution. Lezcano is not one to write rambling things about attributions: if Lezcano says it was a Caravaggio painting, it means he was really convinced it was a Caravaggio painting. Now, if Lezcano crossed paths with Caravaggio he may have done so only in Naples between 1606 and 1607, but not in Rome, because by the time Lezcano arrived in Rome in 1609, Caravaggio was already gone. And yet the Lezcano collection is mostly of second-hand market purchases (there are a few other cases of probable commissioning, but they are very very limited). Again, Lezcano from 1616 to 1622 stays in Palermo, and from 1622 he goes to Naples, then in 1631 he takes inventory, and in 1634 he dies. The collection is dismembered, and twenty-five years later, in 1657, an inventory of the collection of the viceroy Count of Castrillo is drawn up in Naples, which includes an Ecce Homo by Caravaggio, and when his term as viceroy ends in 1658, the Count of Castrillo goes back to Madrid, and that is a sure fact. Is the Massimi painting the Lezcano painting? It should be, because the reports correspond perfectly with Cardi’s and Bellori’s accounts, albeit with the understandable misunderstanding of the oral tradition “it was taken away by the Spaniards” intended as “it was taken to Spain,” whereas they do not correspond to what is inferred from the Massimi inventory. Is the Lezcano painting the Castrillo painting? We have on the one hand the Lezcano inventory in Naples in 1631, in which it is only said thatEcce Homo was “large,” and we have a painting inventoried in Naples in 1657: same city and same iconography, but, in the 1657 inventory, the measurement is five Neapolitan palms, that is, about 130 centimeters, including, however, the ebony frame, so the Castrillo painting may well be the Madrid painting but perhaps also the Genoa painting. We must then add that sometimes collectors gave away the original and had a copy made but more often the opposite happened, for example (we know this precisely because of the story of Caravaggio’s St. Francis of Hartford) Ottavio Costa had a copy made to donate it as an original. This would not be the case with Massimi, but the possibility is possible. However, we do not know what painting was theEcce Homo inventoried in Massimi’s house. Finally, one last point about the Lezcano-Castrillo identity. Franco Renzo Pesenti questioned it because he said that the Lezcano inventory mentions sayón, which would be a henchman, a scherano. While instead the Castrillo inventory talks about soldado. Now, frankly to demand from seventeenth-century inventories such lexical precision seems excessive to me, consequently this does not seem to me to be an argument that would invalidate the identity of the Lezcano painting with the Castrillo painting.

At this point the documents end and the problem of copies arises.

We have in Sicily, at least according to what Longhi published in 1954, a larger copy in the museum in Messina of the GenoaEcce Homo, a version of the so-called “Dortmund” type, which is the one in which there is the soldier with the morion (although by now I want to hope that no one any longer thinks that it can be traced back to an original by Caravaggio), and then we actually have a version of the composition of the Madrid painting, which had passed virtually ignored. Lezcano, after Rome, from 1616 to 1622 went to Sicily: on the island we have attested a copy of the Genoa painting in Messina, traditionally attributed to Alonso Rodríguez, and then we have the copy published by Longhi, whose measurements are unknown. So in both cases the Massimi-Lezcano painting could be clued to be as much the Genoa painting as now the Madrid painting. There is a problem, however, the problem of size: either we must insist on thinking, as I said earlier, that Caravaggio didn’t give a damn about the measurements and made it smaller, or we must conclude that at least the Madrid painting was curtailed. But it presents roughly the same framing as the Sicilian copy, which is old and according to our hypothesis should have been painted before 1622. If it had been cropped, given that the Sicilian copy has the same framing and that, although we have not seen it live, it does not look to me like an eighteenth-century copy (even to Longhi it did not look like an eighteenth-century copy), it is implausible that Lezcano had the painting decurved as early as 1616: mica you cut so early a picture painted shortly before. Moreover, the framing appears perfect as it is now, so that even if it had been cut it would have been only minimally, by a couple of centimeters. To conclude, we hold nothing certain; I have put all known elements on the table.

As for the Genoa painting, many of those who had at least misgivings about Caravaggesque autography now, after the discovery of the Madrid painting, reject it with much more vigor. What is the relationship between the two Ecce Homo paintings?

We had doubts that the Genoa painting is by Caravaggio even before, although in my opinion the Genoa one seems a little more Caravaggio than the Madrid one. But even the Genoa painting is not a foolproof painting, however if it is a Caravaggio, then it is a Roman painting. The Madrid painting (which will have to be cleaned anyway) comes back very badly as a Roman Caravaggio. What if instead we resign ourselves to the conclusion that the Massimi painting is the Lezcano painting, it is also the Castrillo painting, and it is lost and we still do not know what composition it had?

|

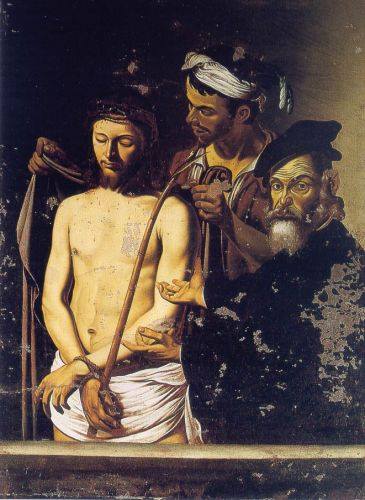

| The work published as a derivation from Caravaggio in Longhi’s 1954 essay |

|

| Caravaggio (?), Ecce Homo (c. 1605-1610; oil on canvas, 128 x 103 cm; Genoa, Musei di Strada Nuova - Palazzo Bianco) |

|

| Alonso Rodríguez, Ecce Homo (oil on canvas, 210 x 108 cm; Messina, Museo Regionale) |

In the event that, for theEcce Homo in Madrid, we should be able to find a consensus on a possible Caravaggesque autography, how should we approach this work given to Caravaggio and yet now encountering increasing doubt and perplexity?

This is where the art historian’s desire for identification comes in: there is an element of desire to see and have what one fears is lost. On this point I think it is not necessary for the Madrid painting to be original. We have a Caravaggio work that is feared to have been lost, and then we hope and wish that it has not been lost instead. We all hope that what is lost is not, we wish for it to come back to light, and then that has conditioned our eye in the case of the Genoa painting. The moment the Madrid painting emerges, even if it turns out not to be by Caravaggio, it can still play (and it has already played to some extent) the role of a picklock to drop the veil in front of the Genoa painting, and then the moment another painting pops up that induces us to say that the Genoa painting is not the right one, this can also simply be interpreted as an acknowledgement that the attribution of the Genoa painting to Caravaggio (which is not outlandish anyway) is nonetheless connoted by an element of hope, of wishful thinking, of an act of goodwill that tends a little bit to condition the eye. So unfortunately it may be that the Madrid painting ends up knocking down the Genoa painting without necessarily coming to take its place.

At the level of reading the painting, what are the elements that, even from a simple view of the image that has been circulating on the Internet, lead you to doubt about a possible autography by Caravaggio?

Basically, the types of faces.

Here,in this regard there has been an insistence on the figure of Pilate, for example.

On this aspect there is to say that this is a private painting, that is, made for private devotion of the client. And the patron could keep it in his bedroom, in his oratory, in his palace. Therefore, it is not conceivable that an artist would have represented himself in it, since the idea has emerged that Caravaggio’s self-portrait of Pilate’s face is seen. If anything, he would have painted the portrait of the patron, but we do not know what face Massimo Massimi had, however, that a Roman nobleman of 1605 could have that tramp seems to me really far-fetched, while Caravaggio with the tramp we have never seen, so this idea seems to me to have no logic, it is dictated by desire, it is not possible that Caravaggio would have portrayed himself with that evidence. We agree that Caravaggio thought he was the best of all, but this was a painting to pray.

One last question. About the hype that has been created around this Ecce Homo, I have been very struck by the unusual consensus that the painting has received, even from scholars who are usually very cautious and prudent, and who instead this time have been very much in favor of a possible attribution. Why do you think this strong consensus has been created?

Because it is certainly is a more serious painting than the vast majority of paintings that have emerged in recent years. First of all, it is a multi-figure painting: in the case of the alleged Caravaggio originals that have come to light in recent years, setting aside the only good ones (the Dublin Capture of Christ and the St. John the Baptist lying down discovered by Maurizio Marini, which, however, almost no one has ever really seen because it sits locked in a bank vault ), it has almost always been single-figure paintings. For single-figure paintings, attribution is always more difficult; a single-figure painting is in the beginning less easy to attribute than a multi-figure painting. The only multi-figure painting that has emerged lately is the Toulouse Judith, but this and other paintings are usually fireworks. Attributions are evaluated over time. I am not saying in 20 years, but in 10 years we will see what has happened to this painting. I think it is difficult for a Caravaggio painting to jump out of a private home in Madrid’s barrio Salamanca: for such an important painting, which does not have an ecclesiastical location, one would expect at least a provenance from a Spanish noble family that has held possession for centuries. Instead, this is a painting about which nothing is known, it is very vague, the provenance must have something important. Here we are at the Van Gogh found in the attic, but for Caravaggio this eventuality is implausible. I think that in time everyone’s eyes will become clearer, including mine. I am optimistic that in ten years I myself will have clearer ideas.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.