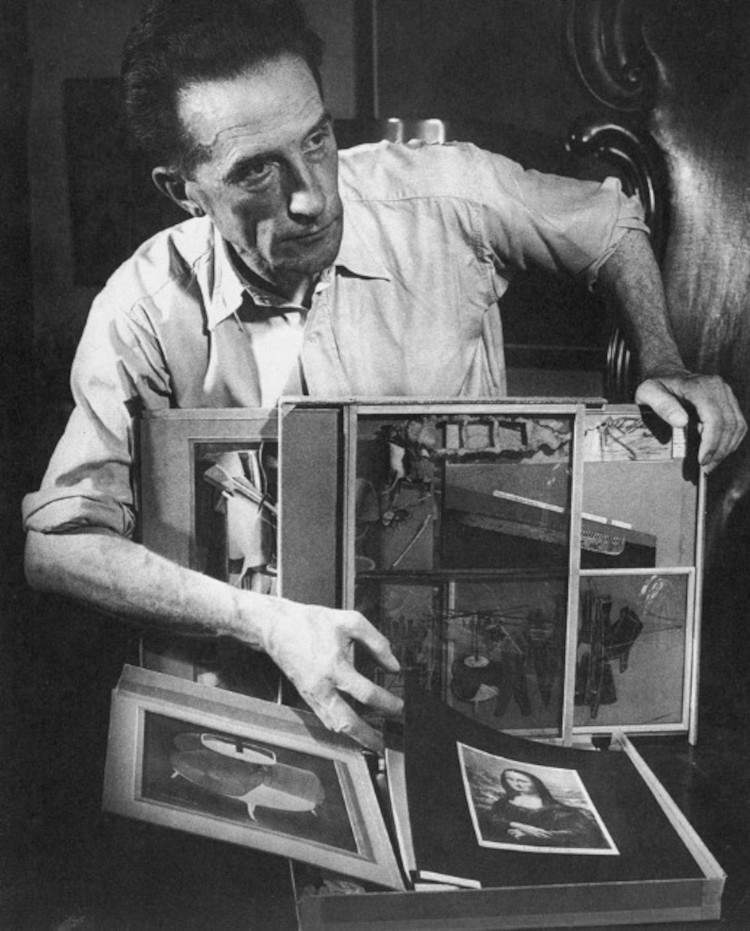

“Everything important I have ever done could fit in a small suitcase,” declared Marcel Duchamp (Henri-Robert-Marcel Duchamp; Blainville-Crevon, 1887 - Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1968). In fact, between 1935 and 1941 the artist worked on a particular project titled by or of Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy [Box in a Suitcase] that brought together sixty-nine miniature three-dimensional reproductions and replicas of his most significant works. In order to carry out this project, Duchamp began to write long handwritten lists with title, date, and location (where known) of the works; he used photographs to reproduce the scattered objects; and he also turned to family members and European and American collectors who owned almost his entire output. In order to personally examine and note specific details of the originals, such as titles, dates, dimensions, he also made short trips to the United States, and on some occasions made detailed studies on the spot, including on colors, jotting down notes, making sketches or photographs. For his own contributions such as frontispieces, book and magazine covers, color illustrations and inserts, to be included in the Box in a Suitcase, he took advantage instead in the late 1930s of the opportunity to obtain the printing of hundreds of additional copies of these to save on expenses.

For this “wonderful vacation in my past,” as he ironically called the work, he relied on to collotype printing, an antiquated, complex, and expensive technique that allowed for extraordinarily faithful copies of the originals, and to pochoir coloring, a type of proxy painting entrusted to artisans who patiently applied pigments to the prints by hand, using matrices cut from zinc sheets for each color area, thus blurring the lines between a handmade original and its mechanical duplication. For added ambiguity, some reproductions were also varnished and framed as real paintings. So during these years he collaborated not only with pochoir workshops but also with specialized artisans such as bookbinders, carpenters, ceramists, glassblowers, suitcase makers, paper merchants, glassy porcelain manufacturers, photographers, and printers to make the small objects for the Box in a Suitcase.

To enclose all these reproductions he also thought of a suitable and original container: at first he thought of a book, but the idea did not fully satisfy him, then came the enlightening idea. A box in which “all my works would be collected as in a small-scale museum, a portable museum so to speak.” He then devised a compartmentalized cardboard box, with a wooden armature and frames and two sliding panels. He also created deluxe editions in plywood cases lined with brown leather, personalized with an original work placed inside the lid. Finally, he completed each briefcase with its own lock and key.

Consider that to compose a single copy of Box in a Case required at least ten days of work and more than one hundred and eighty pieces, from the sixty-nine miniature reproductions and replicas, each with its own label printed on paper, to the black cardboard folders on which almost all the collotype prints were fixed with glue and tape (some as mentioned were framed), as well as the wooden and cardboard supports and metal details. Truly painstaking work.

The first to purchase a Box in a Suitcase was Peggy Guggenheim herself, who reserved No. I/XX of the deluxe edition. It is around this specimen that the current exhibition Marcel Duchamp and the Seduction of the Copy, curated by Paul B. Franklin, running through March 18, 2024 at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, revolves. The first major retrospective that the Venetian museum venue devotes to one of the most innovative artists of the 20th century, who was also a longtime friend and adviser to Peggy herself. Duchamp assembled it for her, with a dedication, “For Peggy Guggenheim this No. I / of twenty boxes in a suitcase / each containing 69 pieces and an original / by Marcel Duchamp / Paris January 1941.” He had the collector’s name and edition number stamped on the leather (from recent investigations it appears to be calfskin) and completed it with a Louis Vuitton lock. And since the deluxe edition was always accompanied by anoriginal work, Duchamp chose for his first purchaser the coloriage original that serves as the prototype for the pochoir-colored collotype reproduction of The King and Queen Surrounded by Quick Nudes (the original painting is dated May 1912 and is in the Philadelphia Museum of Art), where a chess king and queen face each other surrounded by a swarm of female nudes. Inside the suitcase, in the inner half of the sliding left wing, he also placed the framed, varnished and pochoir-colored collotype reproduction of the painting so that, once the suitcase was opened, the unvarnished original coloriage of The King and Queen Surrounded by Quick Nudes would converse with its double. Guggenheim’s suitcase also contains a miniature of Fountain, the inverted urinal known as one of Duchamp’s most famous ready-mades, and a printed postcard depicting the famous L.H.O.O.Q., Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa to which the artist added a beard and mustache complemented by the pun given by the sequence of letters pronounced in French “elle a chaud au cul.”

Marcel Duchamp and Peggy Guggenheim were linked by a long friendship, as is recounted at the Venetian exhibition through archival documents, photographs, and publications. The two met in Paris around 1923, but it was from the fall of 1937 that Duchamp became among the patron’s most trusted advisers, beginning with the imminent opening of her first art gallery in London, Guggenheim Jeune, and the formation of her art collection. Peggy Guggenheim, in her autobiography Confessions of an Art Addict published in 1960, wrote, “I really needed help. An old friend, Marcel Duchamp, came to my rescue [...] I don’t know what I would have done without him. [...] I have to thank him for introducing me to the world of modern art.” With the purchase of the first copy of the deluxe edition of Box in a Suitcase, she then became an early supporter of the artist. Peggy exhibited it in the installation of her new New York gallery, which opened in October 1942: Art of This Century.

Box in a Suitcase should be regarded as the greatest and most innovative example of Duchamp’s use of copying and duplication as a mode of creative expression. Indeed, throughout his career the artist repeatedly reproduced his own works by varying techniques and sizes, and he spread his body of work precisely through copies. For him, the original and its reproduction were of equal aesthetic importance: “[People] say that a machine-made thing is not a work of art. That is ridiculous. [...] A duplicate or a mechanical repetition has the same value as the original,” he declared. And about ready-mades, consisting of mass-produced industrial objects, he stated that these were authentic copies of which there is no original. “There is nothing unique about the ready-made,” he stated in 1961. “The replica of a ready-made conveys the same message.” So much so that by the mid-1930s he began making some lost ready-mades for exhibition purposes, and in 1964, Milan art dealer Arturo Schwarz convinced Duchamp to market an edition of historical ready-mades, given their popularity: however, the artist limited the edition to eight signed and numbered copies.

Marcel Duchamp, the father ofconceptual art, subverted the cultural hierarchies of modernism, which gave greater importance to artistic innovation, to the originality of the author, consequently discrediting the copy, the reproduction. The artist, nonconformist that he was, thus refused to support the exaltation of artistic originals and despised reproductions of any kind. In painting “we have remained with the cult of the original,” but “neither in music nor in poetry,” he argued, is there any such thing as the idea of the original.

Even the full title of Box in a Suitcase itself, “from or by Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy,” is significant because it refers to the idea of the copy, the cloning of himself: indeed, Duchamp created his own alter ego, female, a double of himself. With Rrose Sélavy he ceded authorial autonomy and artistic uniqueness in favor of creative duality, as expressed by the double “r” in Rrose. And from 1921 she also decided to shape it, wearing women’s clothes, putting on makeup, bejeweling herself, thus embodying the figure of the beautiful bourgeois, sophisticated and seductive. Rrose Sélavy had herself photographed by Man Ray, made films, published puns (her very name is based on the French phonetic pun "éros, c’est la vie), and above all made several works of art together with Duchamp, as in the case of the Box in a Suitcase.

Over the course of his career, Marcel Duchamp made as many as 312 examples in different editions of Box in a Suitcase.

Peggy Guggenheim’s original is composed of a wide variety of materials and sees the use of various techniques: calfskin, cardboard, wood, rigid canvas, waxed canvas, velvet, ceramics, glass, cellophane, plaster, metal elements, letterpress printing, collotype and lithography on paper, cardboard, canvas and cellulose acetate with tempera, watercolor, pochoir, ink, graphite, plant resins and natural gums.

This was the subject, on the occasion of the exhibition Marcel Duchamp and the Seduction of the Copy, of an investigation campaign and conservation intervention, conducted in two phases in the restoration laboratories of theOpificio delle Pietre Dure and supported in part by EFG. The results are presented in Marcel Duchamp: a journey into the Box in a Suitcase, an in-depth scientific and educational study proposed by the Venetian museum headquarters on this original work of art. Objectives included identifying the techniques chosen by the artist and reconstructing the method of assembling the pieces, as well as solving the problems related to the conservation of such a delicate object.

As part of the exhibition, the museum is organizing related events. Every day at 4 p.m. in the museum garden is a free presentation lasting about 15 minutes on the temporary exhibition. Also scheduled as part of Kids Day on December 3 is the workshop I ready made by Marcel Duchamp! A workshop for young children, ages 4 to 10, to bring them closer to art in an accessible and engaging way, experimenting with different techniques and themes. Participation is free with online reservation required (starting Nov. 27).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.