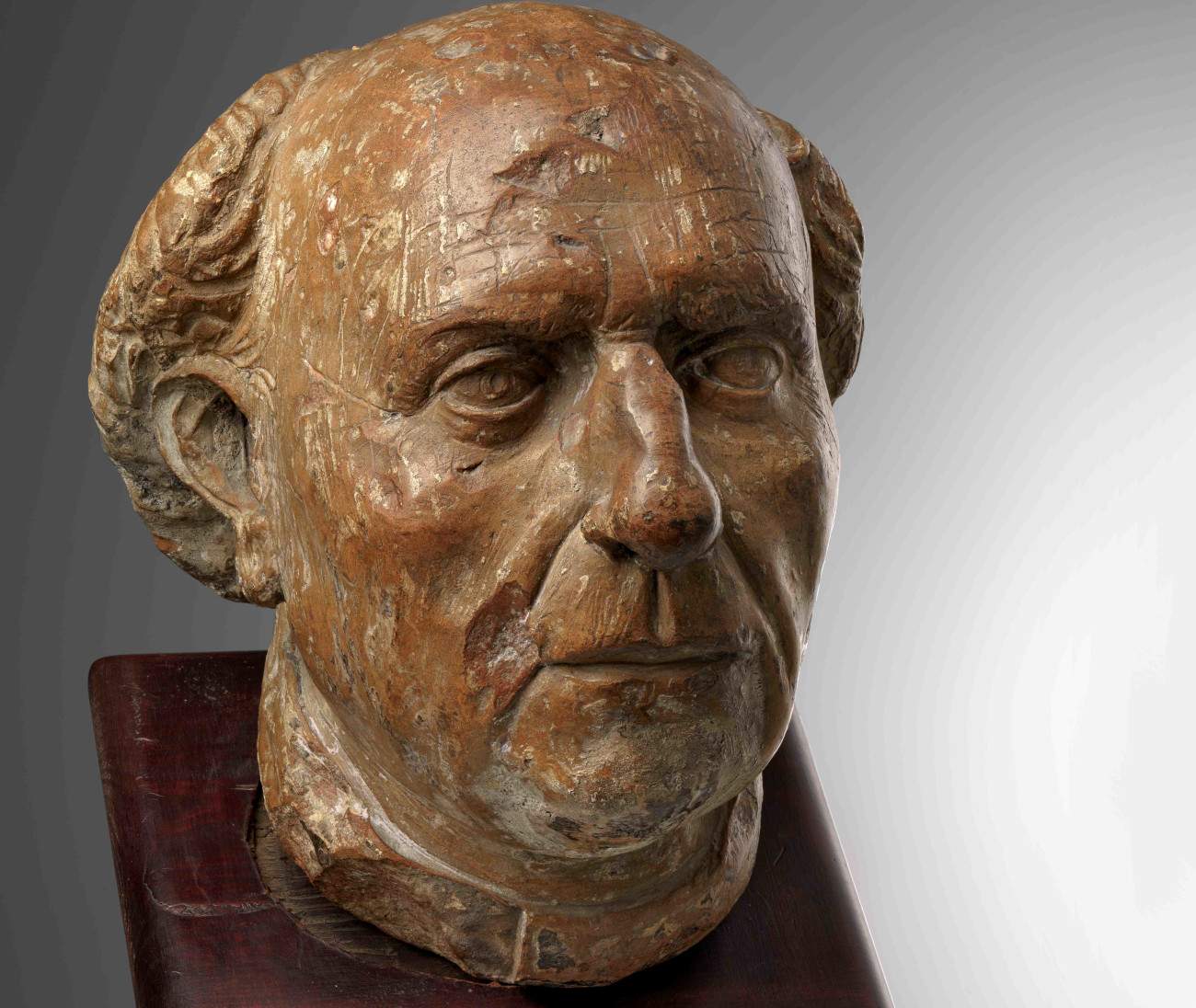

Among the furnishings of a historic home in the Florentine area, an unpublished early Renaissance sculpture depicting Filippo Brunelleschi has been found. It is a terracotta head (25.6 x 22.1 x 20.2 cm) molded without the aid of a cast, shaping a compact, almost full block of clay, as evidenced also by its considerable weight (7.1 kilograms), by Andrea di Lazzaro Cavalcanti known as Il Buggiano (1412 - 1462), Brunelleschi’s adopted son and sole heir, in the aftermath of his father’s death. The sculpture was purchased by the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore for 300,000 euros and will be displayed in the exhibition after restoration and then become part of the collection of the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo.

The discovery is due to art historians Giancarlo Gentilini and Alfredo Bellandi, who identified in this sculpture the model made by Buggiano, presumably between February and March 1447, for the marble bust of Brunelleschi destined for the memorial in Florence Cathedral entrusted to him by the Opera workers of Santa Maria del Fiore.

This is an exceptional discovery, they let the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore know, because, in addition to the undoubted value of Andrea Cavalcanti’s art, portraits of Brunelleschi coeval with or shortly after his death are very rare. Apart from the one in the marble monument in Florence Cathedral and the death mask in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, only two others in painting are known: the youthful profile inserted by Masaccio in the frescoes of the Brancacci Chapel in the Carmine, in the scene depicting St. Peter in the Chair (1427-28), and the much more modest one in the well-known panel in the Louvre Museum, attributed by Vasari to Paolo Uccello and now discussed with a date around 1470. It should be added that it is one of the oldest extant terracotta effigies, not far from the famous bust of Niccolò da Uzzano referred to Donatello or Desiderio da Settignano (Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello), which therefore also constitutes a significant testimony to the rebirth of a genre such as the sculptural portrait among the most representative of the new spirit of Humanism.

“The terracotta head with the features of Filippo Brunelleschi’s face was shaped by Andrea Cavalcanti (the Buggiano), who was Filippo’s adopted son and heir,” said Antonio Natali, adviser to the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore. “It is well known that both had notable commissions from the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore: of Brunelleschi it is not important to say, while of Buggiano the admirable humanist washbasins in the cathedral sacristies and, at this juncture, above all the celebratory monument to Brunelleschi in the cathedral, which has its model precisely in today’s terracotta head, should be remembered. Of which, with these premises, everyone will understand how the acquisition by the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore was even inescapable.”

“We believe that it is truly an exceptional opportunity, an unthinkable privilege, to be able to present the unpublished, vivid portrait of Filippo Brunelleschi, modeled by his adopted son, Andrea Cavalcanti, in the aftermath of his death, say Giancarlo Gentilini and Alfredo Bellandi. As is well inferred from multiple formal and technical aspects, the work we present here is therefore to be considered the model prepared by Buggiano for the execution of the marble portrait. It is a ’lifelike’ portrait, considering that Brunelleschi was notoriously ”small in person and features“ (Vasari 1568), and the measurements of the face (perhaps slightly reduced by the usual ’shrinkage’ of the clay) are basically comparable to those found in the plaster death mask and marble effigy, but compared to the facial cast the image, now devoid of the contraction of rigor mortis, takes on more harmonious proportions harmonious, the face is almost inscribed in a sphere.”

The sculpture is in need of restoration: although intact (apart from a single gap in the chin, which an old, clumsy plaster integration makes it look more extensive), in fact the work has widespread scratches and residues of a chalky glaze and traces of several paint layers (one with apparent naturalistic tones and at least two of brown color, perhaps to simulate bronze, subsequent to the restoration of the chin).

On April 15, 1446, Brunelleschi died at his home in Florence, and Buggiano likely made on the same day and place, where he also lived, the funerary mask in accordance with a usage from the ancient Roman world well known and practiced in Florence. On December 30 of the same year, I Consoli dell’Arte della Lana decreed that Brunelleschi’s body, provisionally laid in Giotto’s Campanile, be buried in the Cathedral. On February 18 of the following year, 1447, the Operai dell’Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore resolved to erect a wall monument in his honor, consisting of his “figure in the natural state” and an epigraphic celebratory ’memorial’ entrusted to Marsuppini. Shortly thereafter, on February 27, Andrea Cavalcanti, who had long been active in the Santa Maria del Fiore building site, received from the Opera the marble needed to make the monument. Between February and March 1447, Cavalcanti made the model for the clipeate bust of the memorial in Florence Cathedral. The monument would be finished in 1447; we know that it was still being worked on in late May when the text composed by Marsuppini was approved. The model, presumably, after the monument was made, was relegated to the sculptor’s workshop among the study and subsidiary materials. The state of preservation of the work testifies to a later reuse as an independent sculpture, probably preserved for a long time with the knowledge of the illustrious identity of the effigy then later falling into oblivion.

Andrea di Lazzaro Cavalcanti, known as Buggiano from the village in Valdinievole where he was born in 1412, the son of Brunelleschi’s sharecropper brother, was adopted at the age of seven by Filippo, already established and influential as a sculptor and architect, who placed him in the main building sites of the Florentine churches where he sculpted remarkable works largely designed by Brunelleschi himself, such as the two splendid washbasins in the Sagrestias of the Duomo and the Medici Sepulcher at the center of the Old Sacristy in San Lorenzo. A prolific and versatile sculptor in marble, wood, terracotta and stucco, he is remembered by Antonio Manetti in the Notizia di Filippo di ser Brunellesco (Vita di Filippo Brunelleschi) (c. 1487) as “his disciple” and “his reda,” and this illustrious city tradition is nourished by Vasari in the Torrentina edition of the Lives where he draws a brief profile of the sculptor who died in Florence on February 21, 1462.

An artist of Donatellian extraction with an austere style of velvety marble delicacy in his children charged with vigorous physiognomic expressionism who populate old-fashioned sarcophagi, basins and Marian reliefs, the Buggiano stands out in the classicist revival of the early fifteenth century for a revisitation of ancient art guided by philological knowledge and adherence to fifteenth-century naturalism inspired by Donatello, Michelozzo, Luca della Robbia, and Bernardo Rossellino-who around 1450 involved him for the crowning of the Bruni Monument in Santa Croce-through whom he declined his composite style with a deliberately archaistic timbre that sets him apart in the stave of Renaissance sculpture.

Image: Andrea di Lazzaro Cavalcanti known as Il Buggiano, Portrait of Filippo Brunelleschi, terracotta head, model of the portrait for the Brunelleschi monument in Florence Cathedral (1447). Courtesy of Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore.

|

| Undiscovered early Renaissance sculpture depicting Filippo Brunelleschi |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.