Viareggio is in danger of losing one of its symbols: the pine trees that dot its coastline and are found in its two large pine forests, the Pineta di Pon ente and the Pineta di Levante. It must be said that for years now the state of Viareggio’s majestic pine trees has not been what it once was: several plants, in recent years, have fallen due to a variety of causes (mainly due to bad weather), and have been replaced with other essences, in particular with holm oaks and beech trees, so that in the pine forests the presence of the pines that also give their name to the two large parks is increasingly sparse. Now, however, the situation is likely to worsen because, in recent days, the Tuscan city’s city council has taken a firm stance that unfortunately goes against pine trees.

In particular, according to Federico Pierucci, alderman for Urban and Territorial Regeneration, “the Levante pine forest has reached the end of its life.” But the problems of the Levante Pine Forest are only part of the issue.

The Pineta di Lev ante is the large park that stretches from the dock to Torre del Lago and then, virtually seamlessly, to the San Rossore Park on the outskirts of Pisa. Of the two pinewoods in Viareggio, it is the more extensive and less “urbanized”: if in fact the Pineta di Ponente is a large public park with avenues and activities (bars, restaurants, kiosks, etc.), the Pineta di Levante is decidedly wilder, and is configured as a vast coastal forest. It also contains two nature reserves, the “Lecciona” and the “Guidicciona,” established to protect the endemic species found in the park. A large piece of Mediterranean scrub has been here since at least the 1740s, when, as in many coastal areas of Tyrrhenian Italy, pines and holm oaks were planted to defend inland crops from the sea winds.

Many of those pines, however, are already gone, devastated by bad weather, disease, and cutbacks. Councillor Pierucci, speaking at a city council meeting last week, let it be known that the pines that will collapse or be removed will not be replaced and that the pine forests will return to being scrub or hygrophilous scrub as they were before human intervention. At most, other plants will come in place of the pines, starting with holm oaks. “It is useless,” said the councilor, “for us to continue planting tree essences [pines] that are neither native nor suitable for a densely urbanized context.”

A decision, therefore, that will forever change the face of the city. And already several felling operations have begun in recent weeks: between April and May, sixteen pine trees were removed on Via Indipendenza (one of the avenues bordering the Pineta di Levante). Another four imposing pine trees over 20 meters tall were cut down in early May. According to surveys by agronomists from Treelab, a company contracted by the municipality to study the plants in the eastern pine forest, these are diseased plants that run the risk of falling onto the road at any moment. The municipality’s choices were rapidly accelerated after a plant collapsed last April 19, leading to the work along Independence Street. According to Treelab, however, there are 27 pine trees between Via Indipendenza, Via Virgilio and Viale dei Tigli suffering from problems resulting from the presence of dead branches and heavy crowns. Still, other pines have severely uplifted root systems and lean on neighboring pines, increasing the risk of collapse. Of these 27 pines, 4 had to be cut down (these are the ones mentioned above). For others, however, urgent safety work was sufficient.

The Pineta di Levante from above. Photo Piero Sant

|

The Pineta di Levante in Torre del Lago (municipality of Viareggio).

|

Cuts at the Pineta di Ponente. Photo by Chiara Vannucci

|

Cuts at the Pineta di Levante, along Viale dei Tigli. Photo by Barbara Carraresi

|

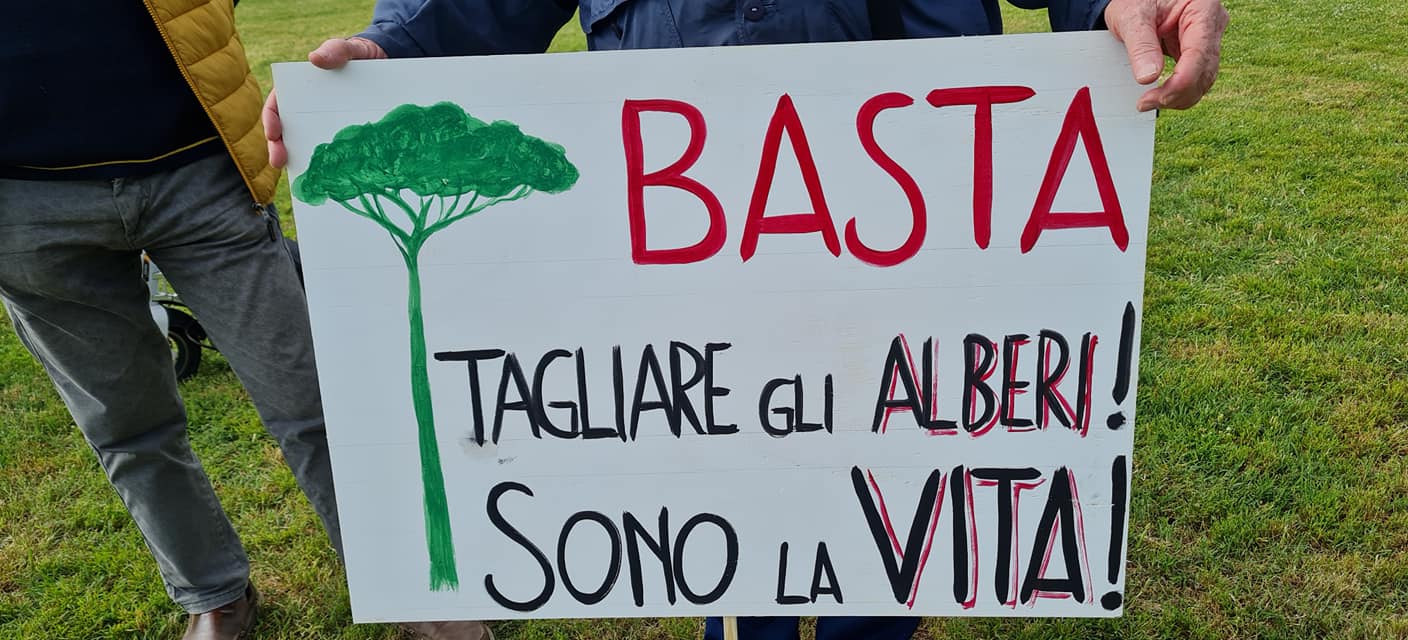

And there are not only the felling of diseased plants, but there are also those that are perceived as completely gratuitous by the population. A stir is brewing over the cutting down of pine trees in Largo Risorgimento, where some of the pines that decorate the lawn have been felled because a parking lot for the Pam supermarket, which is located along one side of the square, will be built here. The store is scheduled to reopen in mid-May. In the area, despite the reassurances of the construction management (instead of pine trees, again, holm oaks will be planted), the day before yesterday, Sunday, May 30, a protest demonstration was held that was quite well attended (about 150 people). There are also doubts about the lawfulness of the operation: “in this period,” writes Anna Luisa Mattei in the Facebook group "Committee for the Salvation of the Viareggio Pine Forest,“ which is very active with several daily updates, ”the nesting of birds is always in progress. In fact, the European Directive 2009/147/EC absolutely prohibits the cutting of tree branches during the nesting period, which is from mid-March until the end of September. Despite this, the municipality of Viareggio authorized the felling without taking into consideration the ecological damage and the regulations in place."

“The project of the parking lot and the new road system has been agreed with the municipality,” engineer Paolo Polvani, director of works and designer, explained to La Nazione. “It foresees, yes, the felling of three plants, in the perimeter around the central building, but in order to restore greenery to the parking area, fourteen more trees will be planted. And specifically, holm oaks have been chosen.” It seems that for the time being the other large pine trees in Largo Risorgimento will not be touched. In any case, the engineer goes on to explain, “the goal is to make a large portion of the parking lot usable for the opening day of the supermarket, and then continue with the completion of the project,” which also includes major changes to the road system. Which will hopefully not affect the plants.

The pine trees at Largo Risorgimento

|

A moment of the May 30 demonstration

|

A moment of the May 30 demonstration

|

Fortunately, a broad movement of opposition to the city’s environmental policy has developed in the city. According to city councilor Tiziano Nicoletti, of Viareggio Libera, trees do not fall because they are old, but rather because of the excessive presence of water in the soil, “and it is a problem that has been known for a long time,” he tells The Nation, “as can be seen from the 2002 - 2018 Pinewood Forest Management Plan, which shows that maintenance is lacking on 55 percent of the 11,600 meters of the drainage network. An atavistic problem that this administration has underestimated. And the neglect is not only operational, but also in compliance with regulations. There is a law of January 29, 1992, that requires municipalities with more than 15 thousand inhabitants to plant a tree for every newborn, and another that requires the mayor, two months before the expiration of the term of office, to disclose the arboreal budget. All this is being disregarded in Viareggio.”

Very harsh is the comment of Antonio Dalle Mura, president of Italia Nostra Versilia: “The city,” he says, “lacks a systemic and organic vision of the environment and related landscape. The picture is discouraging: the greenery, which is going through an involutional phase characterized by episodic overhangs, due to the insults of disastrous or absent maintenance, is subject to summary felling, sometimes dictated by the fear of an overhang sometimes completely incomprehensible and unmotivated. As for trees, Dalle Mura continues, ”especially targeted are the trees along streets and squares. Pine trees are the most affected, but not only them: just think of those squares where all the trees (plane trees) have been cut down and have been turned into parking lots and traffic islands. In the streets they lift asphalt and sidewalks and, judged for the inconvenience they cause, are relentlessly cut down. Even preemptively (or pretextually?), without having caused any harm, as happened with a dozen or so pine trees felled at the Old Station. They are victims of the improper interference of their root systems with digging, milling, compaction, root mutilation, hydrological disturbances ... and equally improper pruning. And this not once, but over and over again on the same trees. Either give up trees or adjust interventions. Maintaining trees, and keeping them in the best possible condition, is a duty."

“We want to remove this veil of hypocrisy that accompanies every cutting operation that is authorized,” Andrea Landi of the Committee for the Salvation of the Pine Forest emphasizes instead. “Under the guise of maximum urgency and the safeguarding of public safety, cuts are being made indiscriminately and, above all, there is no real plan to safeguard it in the future. The situation is there for all to see: we have watched helplessly a very harsh attack on our greenery and our history, and there is no real credible program behind it. When we asked what is planned to maintain the arboreal heritage we received no answer.”

There is opposition from many experts as well. Botanist Stefano Mancuso, a professor at the Faculty of Agriculture at the University of Florence and director of the International Laboratory of Plant Neurobiology, does not think the same way as Councillor Pierucci: in fact, Mancuso, in an interview with La Nazione, explained that pine trees are completely native plants. Alternatively, to say that pines are not native plants is to say that about 80 percent of our vegetation is not. “Pines,” Mancuso said, “have been part of our flora since time immemorial. So what should we do with the cedars of Lebanon? The name itself says they are not from here, yet our gardens are full of them. What about palm trees? Versilia has plenty of them.” Pines “have always been part of our Tuscan coastline, on par with cypresses and olive trees. And I can’t imagine not seeing them anymore.” The real problem, according to Mancuso, is climate change. “To think we can solve global warming by replacing plants,” he explained, “is absurd. The damage will always be greater, with or without the pines.” Journalist Beppe Nelli, on the other hand, referred to the city’s history: “Between Viareggio and Torre del Lago, until the entire 1600s, there were swamps and marshes with widespread malaria. The Republic of Lucca entrusted the Venetian engineer Bernardino Zendrini with the famous reclamation works, not only on the Burlamacca. And between 1740 and 1766 - as studies also published by the Migliarino Park report - it was decided to cut the littoral forest to plant maritime and domestic pines with a double purpose: to improve air quality, and to hinder the sea winds that would have damaged agricultural crops in the fields wrested from the marsh. Edicts of the time also mention pine forests as resources to be cultivated: for wood for shipyards, and for pine nuts for food. Incidentally, until the 1990s the municipality gave paid permits for the commercial harvesting of pine nuts, taking them away from the free search of families for domestic use. But the city forgets. And it is curious that the Superintendency, so dogged in not wanting to have the wall of the narrow and dangerous Via dei Lecci moved because it is a historical sign of the Bourbon Estate area, does not move a finger for the preservation of quite another centuries-old sign, the Pineta di Levante.”

And there are those who are mobilizing. In fact, citizens have launched a petition on Change.org directed to Viareggio Mayor Giorgio Del Ghingaro, Environment Minister Sergio Costa and Tuscany Region President Eugenio Giani to ask them to save the city’s tree heritage. “The once green city with large trees,” the text reads, “are being hastily cut down, with cuts that are gleefully publicized by the mayor himself on social media. Extreme pruning practices are carried out by inexperienced personnel under the guise of dangerousness of the plants, which, instead subjected to such practice, become diseased and lose stability.” “At a time when the whole World is heading in a more ecological direction,” the petition concludes, “we cannot afford to go against the tide.”

|

| Viareggio is in danger of losing a symbol of its heritage: its majestic pine trees |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.