“I had to pay 200 euros to publish in an international magazine some photos of materials from an excavation I directed.” “I refused to pay 50 euros for a photo of mine of a piece in a museum, which, moreover, had already been edited. Not because of the 50 euros (actually a pittance, the payment of which required, among other things, a series of arduous procedures), but on principle: I thus preferred not to include that photo in an article of mine in the proceedings of a conference.” “I am in despair, we have some books ready, the outcome of the work of many people, years of effort to study and now finally publish old excavations that remained unpublished: I thought it was a meritorious action, but now I would have to pay thousands of euros for the publication of photos moreover made by us. You can’t imagine the embarrassment of even the officials, who advise me to wait hoping that something will change.” “I am about to publish an article without pictures in which I will specify that I would have liked to include a series of photos, but that current regulations do not allow me to do so.”

These are just a few of the many testimonies of university colleagues, who prefer to remain anonymous (I understand them, retaliation is always lurking and those who have excavation concessions or authorizations for studies fear their revocation, as the current “bourbon” regulations in this area provide). I have known cases of real odysseys, with exchanges of dozens of e-mails, protocolled letters, requests for quotations with 16 euro revenue stamps, payment of a few euros on postal account slips: all in order to publish the results of a research in a popular journal widely circulated in an Italian territory so as to account (dutifully) to a wider public for the work, carried out with public funds.

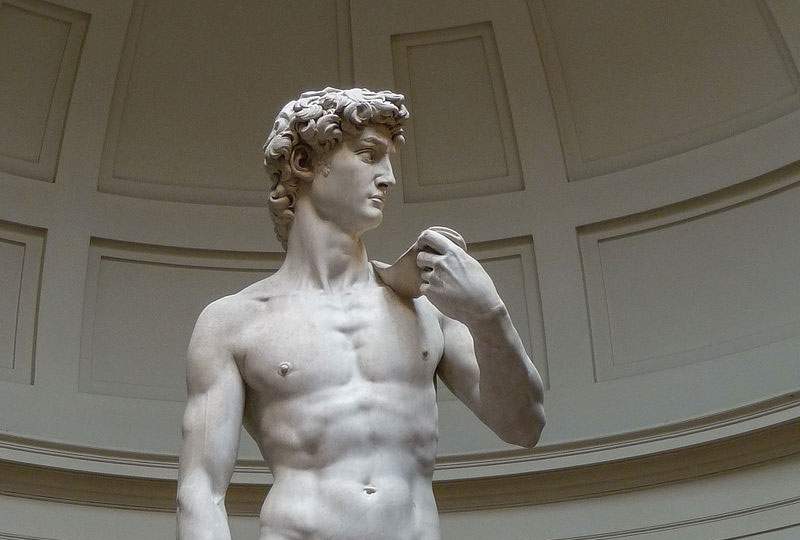

Faced with such absurdities imposed by an anachronistic ministerial decree (DM 161/2023), reactions are the most diverse. There are some (including the writer) who propose civil disobedience even at the cost of facing a lawsuit. There are others (most) who adopt an “Italic” variant of civil disobedience: you pretend nothing is happening, you publish as you have always done, you don’t ask for permission, no one checks anyway. Effectively, apart from scientific publications, which account for a tiny part of the use of images, who will ever challenge foreign tourist agencies or producers of various junk (from miniature coliseums and towers of Pisa to aprons with the lower part of the David, from posters to magnets) for payment for the use of images of cultural heritage? Will the Ministry of Culture put in place a task force that will initiate litigation with hundreds of countries, with the most diverse legislation, or will it send teams of officials in front of the Colosseum and in Piazza dei Miracoli to seize various objects displayed on stalls?

Then there are other solutions that are even more paradoxical. Some have proposed a subterfuge that well illustrates the nature of the ministerial decree and the philosophy behind it. It would be enough to make the publication appear as having been made or promoted by an institution of the Ministry of Culture, perhaps adding among the authors the names of its employees: this would exempt one from paying fees. In short, if the person who publishes the image of a vase, an architectural piece, or a monument is a university or a free researcher not structured in any institution, one has to pay the fee, with all the byzantine procedures involved; if it is an official or manager of the Ministry of Culture who does it, there is no problem.

I can find no other definition to describe this abuse: “proprietary conception” of cultural heritage, not only in its materiality but also in the immateriality of image.

Even publishing houses are running for cover, worried that they will have to cope with onerous demands that would put them permanently in crisis. So they are asking authors, as has also happened to the writer, to sign releases. In this way (contrary to Minister Sangiuliano’s claim that it was the publishers who would pay, perhaps ignoring that in the field of scientific publishing one does not sail in gold), of course and inevitably, responsibilities and costs are passed on to the authors. Faced with this situation, there are publishing houses that are considering no longer publishing volumes on art and archaeology or resorting only to images of cultural heritage from other countries, or - an extreme decision - no longer publishing photos, but only plans and drawings. So much for promoting culture, supporting cultural and creative enterprise, and the much rhetorically flaunted Made in Italy!

Ministerial Decree 161, which actually has as its sole objective to make cash (preferring the pittance of fees on images instead of fostering overall economic, employment, and social growth produced by cultural heritage), is also having worrying implications for other autonomous administrations in the field of protection. The Region of Sicily immediately rushed to ask museums and parks to update their fees, increasing the minimum fees specified in the ministerial decree. The Capitoline Superintendency is also moving in the same direction.

Instead, it is precisely from the entities that a strong signal in the direction of liberalization could and should come. Will Roma Capitale do it with Mayor Roberto Gualtieri and an alderman, a leftist intellectual, like Miguel Gotor? Will ANCI president and mayor of Bari Antonio De Caro do it? Actually, it seems to me that the nefarious scope of this decree is not fully grasped. But, unfortunately, perfectly overlapping positions emerge on the right and the left.

Even the announced revision, which follows the strong protests that have come from various quarters (university councils, scientific societies, the National University Council, the Academy of the Lincei, etc.), as far as we can tell from the first rumors circulating, puts a patch but does not solve the problem. It would, in fact, exclude from payment scientific journals and Anvur band A journals, “scientific volumes with popular and didactic content aimed at the dissemination and enhancement of cultural heritage with a circulation of up to 3,000 copies,” and “newspapers and periodicals in the exercise of the right-duty of reporting.” There are undoubtedly steps forward, but the response, after protests from academia and publishers, smacks of corporate privilege. Some university colleagues will be pleased (this pact is also the work of CRUI and ANVUR) but personally I am not at all, because it corporately isolates the world of the university and research from society. One sector is being favored and the broad sector of free research (especially in the humanities), popular journals or those promoted by associations, foundations, various societies is being harmed. Who will decide what is scientific and what is not? Will the university professor not pay while the local historian, the unstructured scholar, the amateur will continue to be subjected to the gestapo? And what, then, is meant in this sphere by the right to report? Just the news of the latest sensational discovery, complete with the minister’s statement about Italy’s wonderful cultural heritage infused with the nauseating rhetoric of beauty?

But above all, it escapes, at this moment of almost absolute aphasia, the heart of the matter: the affirmation of the proprietary vision of cultural heritage, extended also to the immateriality of images. What Roberto Caso rightly called a “pseudo-intellectual property” or a “pseudo-right of commercial exploitation,” while Giorgio Resta spoke of a “legal monster.”

Alongside this “monster” is another, even more dangerous one: the improper extension of Article 20 of the Cultural Heritage Code. In fact, the Code refers to physical damage (“Cultural goods may not be destroyed, deteriorated, damaged or used for uses that are not compatible with their historical or artistic character or such as to be detrimental to their preservation”) while the DM the extends this dutiful prohibition to the use of images, strong now even by highly questionable judiciary rulings, such as the one on Michelangelo’s David, which have resorted to a supposed “national cultural identity.” At this rate, transformation into an ethical state, deciding what is good and what is not good, is just around the corner. Will the Ministry of Culture also set up an ethics police to preemptively target uses deemed detrimental to the new religion of cultural heritage? To preventive bans I much prefer the risk of unpleasant, uncultured, even vulgar use (such as the influencer Venus of the Ministry of Tourism), far from our taste (which by definition is a personal thing and very much related to the evolution of the times), to be fought with the weapons of culture, politics, irony, satire.

In short, the matter of the use and reuse of images of cultural heritage touches on issues much more important than the payment of duties and taxes themselves; it concerns the very idea of the role of cultural heritage in contemporary society, the fundamental constitutional principles of freedom of research, participation, promotion of the development of culture, freedom of thought, freedom of private enterprise, and subsidiarity.

It is a matter of deciding whether the Faro Convention was ratified by Parliament only to be put in a drawer or to be implemented. It is a matter of deciding whether Italy remains a country stuck in the twentieth century or whether it finally embarks on the path of a modern, secular, free, European country that puts the public interest (which does not simplistically coincide with the state interest), that is, the interest of citizens, at the center.

For an in-depth look at these issues, I now suggest reading Le immagini del patrimonio culturale: un’eredità condivisa?, edited by D. Manacorda and M. Modolo, Atti del Convegno (Firenze 12 giugno 2022), Pacini editore, Pisa 2023, which contains many contributions with different points of view and various experiences, and also to consult the special issue 2, 2023 of Aedon, an online, open-access(https://aedon.mulino.it/archivio/2023/2/index223.htm) journal of arts and law with numerous contributions from the legal and other fields.

This contribution was originally published in No. 20 of our print journal Finestre Sull’Arte on paper. Click here to subscribe.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.