Before we start talking about the case of Piero della Francesca’s Madonna of Mercy, which has been split off from its Polyptych (one of the greatest masterpieces of the Italian Quattrocento) and sent to Milan for the Christmas holidays, a clarification is in order: it is very difficult to define as"exhibitions" vacuous displays such as the one that in Palazzo Marino these days sees the Madonna as the sole and undisputed protagonist. It is not an exhibition: it is a useless display devoid of any logical criteria, underlying which there is not the slightest scientific premise and which metaphorically punches art history, mortifying it and denying the deepest sense of the discipline.

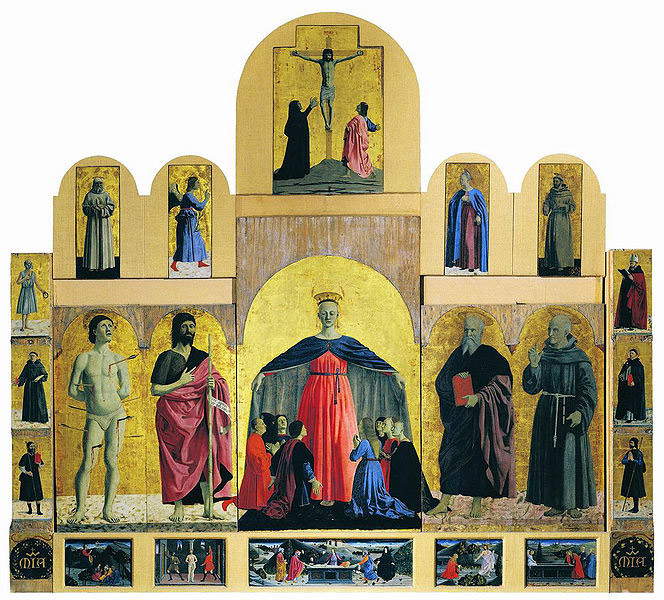

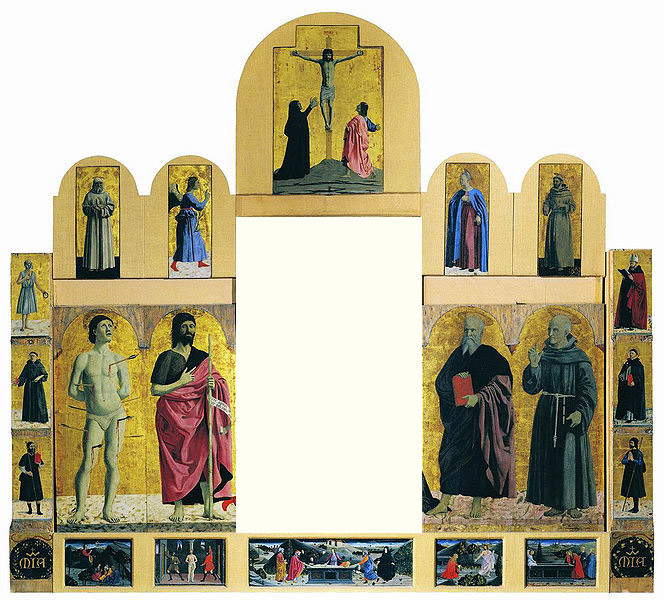

What happened is now sadly known: at Palazzo Marino, for some years now, exhibitions of a single painting have been organized for the holidays, and this year the choice fell on the central panel of Piero della Francesca’s Polyptych of Mercy, preserved at the Museo Civico in Sansepolcro. A unitary complex, broken down in the seventeenth century (a time during which the original frame of the polyptych was destroyed and the panels were reassembled within a heavy Baroque-style apparatus), reconstructed in 1892 by restorer Giuseppe Parrini and philologically rearranged between the 1960s and 1970s, after a restoration conducted at theIstituto Centrale del Restauro in Rome (1959-1960) and the museum’s refurbishment (1975). The panel with the Madonna of Mercy was thus disassembled, separated from the others, and sent to the Lombard capital, leaving the central compartment of the polyptych empty: and perhaps it is not even necessary to emphasize how clumsy, brutally crude, and absolutely unjustifiable in every respect (scientific, conservative, logical) the dismemberment, even if only temporary, of a whole that has survived almost six centuries of history almost unscathed is. A mutilation that, it should be made clear, was already completely inappropriate in the context of a real exhibition (the one on Piero della Francesca held last spring in Forlì), and that becomes even more intolerable if the painting becomes the sole protagonist of an empty and meaningless display, good only to renew a Christmas tradition that could, however, easily do without Piero della Francesca.

|

| Piero della Francesca, Polyptych of Mercy (1445-1462; oil and tempera on panel, 273 x 330 cm; Sansepolcro, Museo Civico |

|

| An image to give an idea of the absurdity of the operation |

Add to this the statements of the mayor of Sansepolcro, Mauro Cornioli, who in aninterview with La Nazione di Arezzo wanted to point out that “if Milan has requested only the central panel, it is also out of a matter of respect and dignity toward Sansepolcro, making sure that those who visit our museum for the holidays can still enjoy the other pieces that make up the polyptych and which are more than twenty.” These are phrases that can only be uttered by those who are totally unfamiliar with art history and who see the works solely as a tourist attraction. Tourists (and visitors in general) of whom one has a very low regard, moreover, if one thinks that they can be “content” to see the remaining panels of a deliberately dismembered polyptych, deprived of its central panel. And likewise, there can be no possible reasons to justify amputations of this kind on the basis of “renewed context” or “particular setting” or “different eye” in which or through which to view the masterpiece: it makes as much sense as hypothetically observing a polar bear deported to a savannah. There are no “different eyes” or “special arrangements” for a panel that was born for Sansepolcro, has a history that has settled down, lives in relationship with other panels that the author intended for them to remain united (although that relationship has been profoundly altered over the centuries), and that inevitably suffers any displacement, since a fifteenth-century wooden panel is an extremely delicate object that should raise a thousand questions about the preservation and appropriateness of the transfer even when about to be moved for a high-level scholarly exhibition. Let alone if the relocation is for an exhibition-sized Christmas strenna. Obviously any damage that the central panel might suffer from the move (there is no such thing as a zero-risk move: a detail that too often we tend to forget) would affect the entire polyptych, the latter being, as already reiterated, a unicum that needs to be thought of in its integrity. Would anyone consider cutting out the landscape from the figure of the Mona Lisa for display separately? Although the central panel of the polyptych is physically separated from the others, the relationship that binds it to the side compartments, the predella and the cymatium, is identical to that which binds the landscape of Leonardo’s painting to its protagonist. Indeed, perhaps it is even stronger.

Laughable, finally, are the reasons given in the presentation of the exhibition on the website of the City of Milan: according to the text, “Lesposizione will lead to a better knowledge and appreciation among the general public of a work considered among the greatest achievements of Italian Renaissance art.” It is truly absurd, surreal to think that one panel of a polyptych forcibly divided from the others can lead to “better knowledge and appreciation among the public.” And in the face of such paradoxical justifications it is also difficult to comment. One might just wonder where the Superintendence is, but the only answer that comes to mind is the one Tomaso Montanari gave five years ago: if in the system of protection there is a “low church” that tries to “stand up to local powers in the name of preservation and cultural dignity and of the works and the territory,” its counterbalance is a “high church” that instead “is totally subservient, and ultimately complicit, to political power - central, local and of all colors -, and ends up systematically betraying its own mission by endorsing and riding on the most far-fetched initiatives of ’valorization’ of the works that it would instead have the duty to safeguard.”

However, in anticipation of the obvious grievances on the part of the people of Biturgia (who have nonetheless murmured and continue to murmur quite a bit), it was decided to include the loan as part of a collaboration with the Municipality of Milan, which should guarantee Sansepolcro the organization of two exhibitions, scheduled for 2017: one dedicated to Roberto Longhi, who will bring to Tuscany Caravaggio’s Ragazzo morso da un ramarro (the role of the City of Milan will consist in mediating with the Longhi Foundation, owner of the work, to ensure that Sansepolcro will be able to secure the loan), and the other dedicated to Luca Pacioli, which will see the exhibition, among others, of a number of works owned by the City of Milan (the Head of Leda attributed to Leonardo and kept at the Castello Sforzesco, two antique printed editions of Luca Pacioli’s Summa and De divina proportione, and two manuscript documents) and Giampietrino’s Madonna and Child, kept at the Poldi Pezzoli Museum, the loan of which will again be brokered by the City of Milan. About the projects that will support these two exhibitions it is not yet known (however, the names of the curators, respectively Maria Cristina Bandera and Stefano Zuffi, give hope), but it is nevertheless unacceptable that in order to send works to Sansepolcro a fragile panel, which should be moved only in case of pressing urgency, and whose extrapolation from the context necessarily entails the alteration of a very delicate balance, is asked as a quid pro quo.

Of course: one can safely assume that it is naïve to oppose an entirely well-established way of understanding works of art, such as the one that sees them more and more like figurines to be exchanged for promotional or commercial deals, or even worse as Pro Loco employees sent here and there to advertise the small village where the masterpieces are kept (the same inconceivable logic according to which dozens of enthusiastic mayors sent their works last year to the Expo in Milan: it would be interesting to know whether tourist presences in their territories have actually increased this year), as pawns in networks of relationships within which many local administrators, who often have zero knowledge of art history, press the organs in charge of protection to grant loans. However, it must also be said that, in the meantime, we are not alone: because, in the case of the Misericordia Polyptych, the voices opposing the loan (which also gathered in a petition signed by hundreds of citizens) were many, although the media tried not to give them too much weight. And then, in the depressing context that sees in newspapers and television a florilegium of articles and reports that, almost unanimously (and often written by journalists even then lacking knowledge on the subject), sing the praises of the operation without asking questions and without advancing the slightest doubt, I believe that making a minimum of opposition is still vital. Art history depends on it.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.