by Redazione , published on 24/09/2020

Categories:

Travel

/ Disclaimer

A visit to the village of Lucignano, in the province of Arezzo, which still retains its layout as a medieval fortified village and where there are valuable works of art, including the famous Lucignano tree.

Tree of Life, Golden Tree, Tree of Love, Lucignano Tree. These are some of the names tradition has ascribed to one of the most famous reliquaries in the history of art, an extraordinary work of goldsmithing two and a half meters high, a splendid gold and coral object in the shape of a tree, unique for a reliquary. Yet little is known about this extraordinary work, one of the symbols of Lucignano: even the chronological extremes, between 1350 and 1471, give us a rough idea of the period of its creation, a time of great flowering of Arezzo goldsmithing, but they tell us little precisely. It was perhaps designed by Ugolino di Vieri, one of the greatest Sienese goldsmiths of the 14th century. It was formerly located in the church of San Francesco: one can only imagine the amazement of those who were to see this admirable late Gothic work inside the temple, this tree surmounted by a crucifix and a pelican, with its twelve branches, six on each side, ending in medallions and on which the goldsmith had grafted coral sprigs, allegorical references to the blood shed by Christ on the cross. An awe that continues to move the minds of those who today see the ’Tree of Lucignano, no longer in the church, but in the local Municipal Museum. Especially lovers: according to a local tradition, the sight of the tree is in fact a good omen for couples.

The museum itself is a kind of long narrative of Lucignano’s history: it is housed in the thirteenth-century Palazzo Pretorio, where for centuries power was administered on behalf of the Republic of Siena, to which the village was subject until 1554, the year of the fall of the Sienese and the passage of the entire republic under Medici rule, evoked by the Medici Fortress that looks down on the village from above, isolated on the hill situated opposite the one on which Lucignano stands. The museum alternates between works by Bartolo di Fredi, Niccolò di Segna, Luca Signorelli, and other important Sienese artists of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries or by authors who worked for Siena at that time: the abundance of works executed by the mid-sixteenth century clearly attests to the moment of the village’s greatest development.

|

| The tree of Lucignano. Ph. Credit Museo Comunale di Lucignano |

|

| Bartolo di Fredi, Madonna Enthroned with Child, Saint John the Baptist and Saint John the Evangelist. Ph. Credit Visit Lucignano |

|

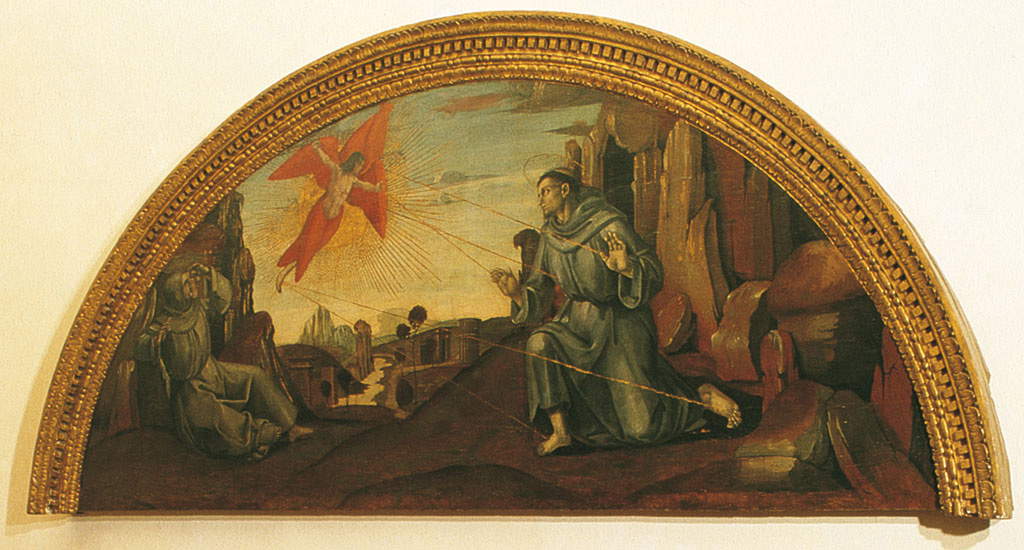

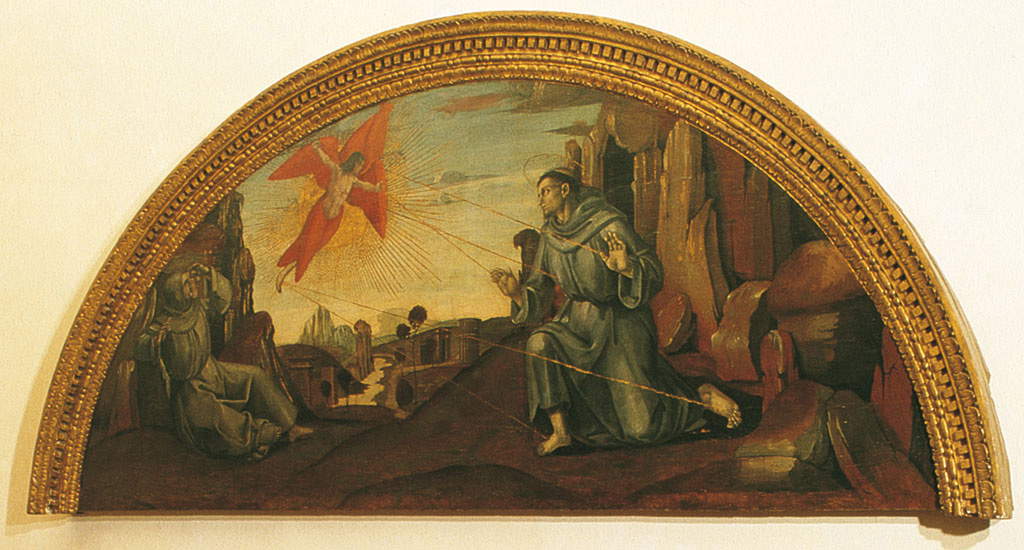

| Luca Signorelli, Stigmata of Saint Francis. Ph. Credit Visit Lucignano |

|

| View of Lucignano |

|

| View of Lucignano |

And the layout of the village itself has remained unchanged: a kind of ellipse, dominated by the towers of the Cassero, that is, the medieval Sienese fortress that was meant to protect the village, and where the streets go round and round, creating concentric circles and leading to the two central squares, the Piazza del Tribunale and the Piazza della Collegiata. It is on the latter that stands the collegiate church of San Michele Arcangelo, one of the buildings entirely rebuilt in the Medici era: characterized by its unfinished facade, its interior is a sort of small museum of seventeenth-century Florentine art, since there are works by Matteo Rosselli, Onorio Marinari, Giacinto Gemignani, that is, some of the most important artists who worked in and around Florence in the seventeenth century.

To find the Sienese Lucignano, the most intact medieval Lucignano, one has to penetrate into the oldest part of the village, among the stone houses that squeeze the alleys that start from the Piazza del Tribunale, and arrive at the terrace on which stands the church of St. Francis, with its black-and-white striped facade, particularly unusual for a Franciscan church, and which therefore must have been devoted to sobriety: the interior has suffered the ravages of time and is, therefore, largely unadorned, but there is no shortage of some very important evidence, and not only for Lucignano. Thus one can linger over the triptych by the Sienese Luca di Tommè on the high altar, where the castle of Lucignano is also reproduced at the time thework, or on the frescoes of the 14th and 15th centuries, among which the Triumph of Death attributed to Bartolo di Fredi is certainly striking, a usual theme for the time, which reminded the faithful of the transience of life, and which here is declined with the elegant intonations typical of Sienese painting (though without the equally typical preciosity: after all, this was still a Franciscan church).

More ancient, however, are the origins of this village in the Val di Chiana. It seems, in fact, that the hill was already inhabited at the time of the Etruscans, but it would later be the consul Lucius Licinius Lucullus (the same famous for lunches, hence the well-known adjective) who founded a castrum there, and it seems that the ancient name of Lucinianum derives from him. Instead, the present layout, that of a fortified village built on the top of a hill located along the communication routes between Siena, Florence and the south, dates from the 13th century. The Medici then left the mark of their domination there quite evident: the main gateway to the village, Porta San Giusto, bears their coat of arms of enormous proportions above the arch. It is from here that, turning right, Via Matteotti starts, formerly known as the “rich street,” because the palaces of wealthy families overlooked it, and even today it is a succession of elegant Renaissance buildings. The “poor street,” or today’s Via Roma, was on the opposite side of the village: uphill (as opposed to the “rich street,” which is instead on the level), narrower, and winding through vegetable gardens and low stone houses that in ancient times were the lodgings of the humbler classes, and where the small workshops of artisans were located. It is among these streets that every year the “Maggiolata”, a procession of colorful floral floats from the town’s districts, which compete to see who can put up the most beautiful float, is held in the spring and evokes the ancient festivals that Lucignano’s peasants used to give to celebrate the arrival of the beautiful season. We can still imagine them, observing the panorama of the Chiana Valley from the top of the village, returning to their homes from the lush countryside surrounding Lucignano.

|

| The church of San Michele |

|

| The church of San Francesco |

|

| Luca Signorelli, Stigmata of Saint Francis. Ph. Credit Visit Lucignano |

|

| One of the floats of the Maggiolata. Ph. Credit Ivo Civitelli - Maggiolata lucignanese |

Article written by the editorial staff of Finestre sull’Arte for UnicoopFirenze’s “Toscana da scoprire” campaign.

|

| Lucignano, a medieval castle in the Chiana Valley countryside |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.