by Redazione , published on 12/11/2020

Categories:

Travel

/ Disclaimer

A trip to the village of Poppi, the "capital" of Casentino, in a silent land of Romanesque parish churches, hermitages, castles, literary, artistic and fairy-tale suggestions.

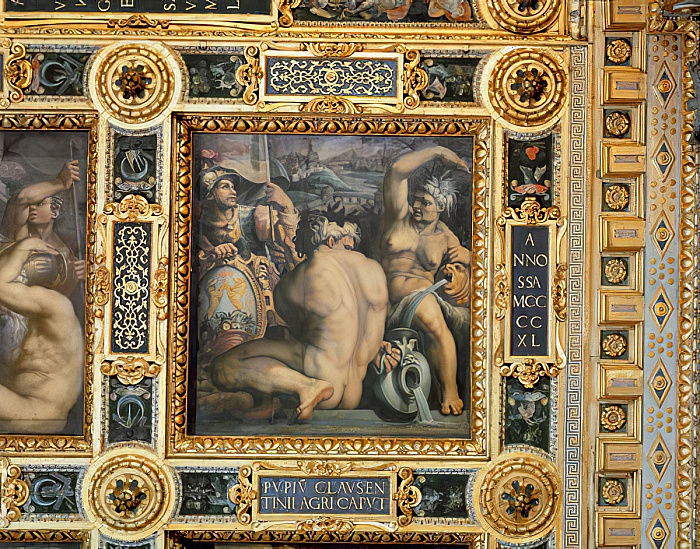

Pupium Clausentinii agri caput, or “Poppi, capital of Casentino.” Next to a year, 1440, the date from which the village of Poppi became part of Florentine rule. So reads the inscription that Giorgio Vasari, in the ceiling of the Salone dei Cinquecento in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, inserts under the allegory of the land of Casentino, of which Poppi is the main and most important center. A village that rises around its castle, which dominates a hill that rises in the middle of the plain that the Arno forms as it flows through the Casentino forests: all around, forests and silent countryside, castles, hermitages and Romanesque parish churches. Camaldoli is not far from here; the places of Franciscan mysticism are not far from Poppi. The town was formerly the seat of the Guidi counts: then, like so many of the family’s fiefdoms scattered here and there throughout Tuscany, Poppi too became Florentine. But the history of the village before 1440 has moments that are anything but negligible. Not far from here, on the plain of Campaldino, the Battle of Campaldino was fought on June 11, 1289, between the Guelphs of Florence and the Ghibellines of Arezzo, victorious for the Florentines: a 24-year-old Dante Alighieri also participated. The poet would later return to these parts, staying in Poppi twice (first in 1307, then in 1311), and a tradition has it that here Dante composed Canto XXXIII of the Inferno, that of Ugolino della Gherardesca, and it seems that it was precisely from Poppi that he managed to maintain contact with the noble family. The current layout of the village, moreover, is due precisely to the Guidi counts.

To literary suggestions are then added artistic ones: One of the most important Tuscan painters of the 16th century, Francesco Morandini (nicknamed, in fact, “il Poppi”), was from Poppi, the author of paintings preserved in churches and museums in the territory (as well as in those in Florence), and to whom critics have recently attributed one of the most discussed and controversial in recent years, that Tavola Doria which is one of the oldest evidence of Leonardo da Vinci ’s lost Battle of Anghiari (and Anghiari, moreover, is very close to Poppi). And in ancient times Poppi was a center of considerable strategic importance: it was halfway between Florence and Arezzo, and above all it was the most important village before the mountains, on the road leading from Tuscany to Romagna.

|

| Francesco Morandini known as Poppi (?), Tavola Doria (1563?; oil on panel, 86 x 115 cm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries) |

|

| Giorgio Vasari’s Allegory of Casentino |

|

| View of Poppi |

The lower part of the village is lined with elegant Renaissance buildings and a string of porticoes unusual for these areas, leading to a fork in the road on which stands the unique 17th-century church of the Madonna del Morbo, conspicuous with its porticoes surrounding it on all sides and with its dome enclosed by a lantern, reminiscent in miniature of that of the Duomo of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence. It has a fascinating history, moreover, since it was built (between 1657 and 1659) thanks to a kind of popular shareholding: it was the citizens of Poppi who covered the costs of the construction, so much so that it was fixed by statute that the owner of the building should be “the people of Poppi.”

If one chooses to go straight ahead, the porticoes that flank the whole of Via Cavour bring the traveler directly in front of the severe flank of the Romanesque abbey of San Fedele, which closes the village on the north side. It dates back to the 10th century, and was formerly a Benedictine monastery, later to become Vallombrosian: historical vicissitudes led it, over time, to lose its original appearance, which was rebuilt with the restorations of the 1920s and 1930s. Today, it preserves works by Tuscan artists of all periods, starting with Francesco Morandini himself, whose Martyrdom of St. John the Evangelist is featured. Morandini is also encountered in the nearby prepositura of San Marco, where a splendid Deposition can be admired.

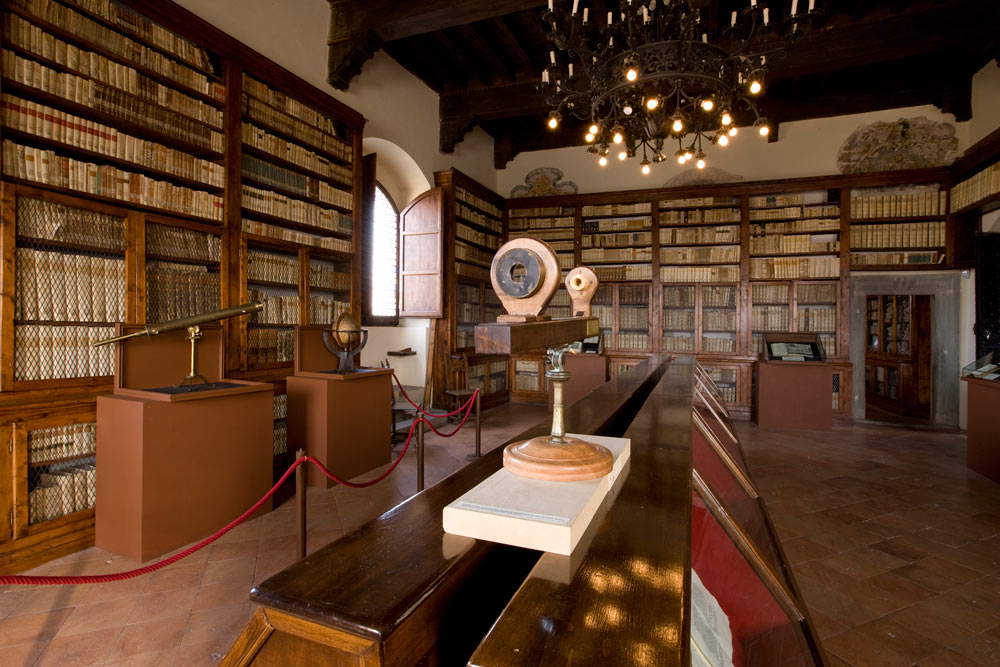

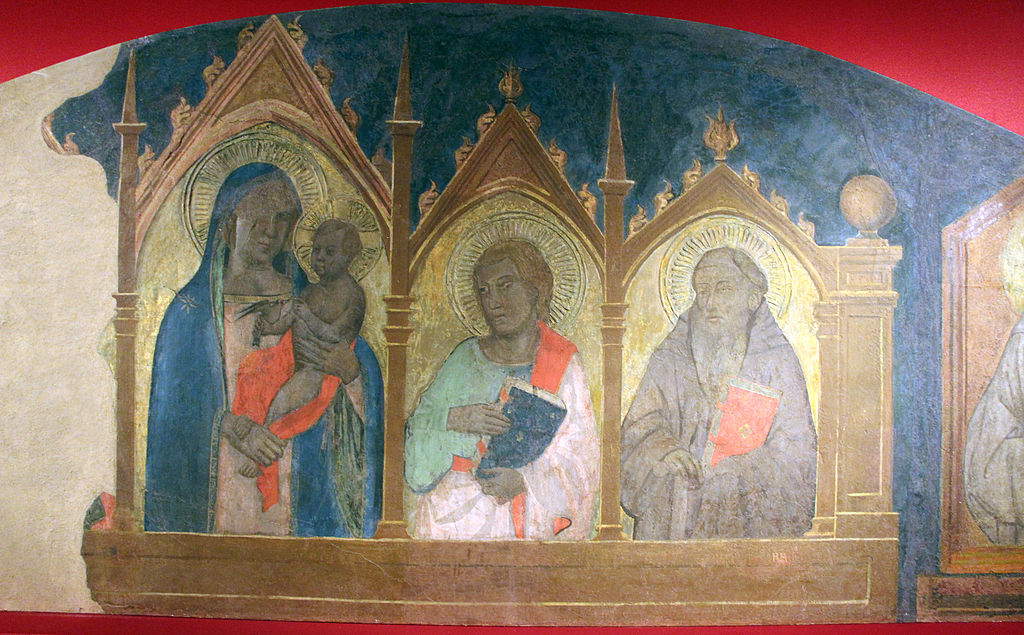

Returning to Madonna del Morbo, one can turn around it to take a steep uphill road that leads to the Castle of the Counts Guidi, one of the most recognizable pieces of architecture in all of Casentino, with its tall tower that can be glimpsed even from miles away. Once the residence of the counts and later the seat of local power, it now houses a museum that traces the events of the Battle of Campaldino, the Rilliana Library (where there is a historical section some twenty-five thousand volumes strong and where, above all, the conspicuous collection of medieval and Renaissance manuscripts and incunabula that Count Fabrizio Rilli Orsini donated in 1825 to the municipality of Poppi is preserved: in particular, the collection of 930 incunabula is one of the most important in Italy), and a documentation center. But you can still visit the chapel, where one of the most astonishing fresco decorations in Tuscany is preserved, with cycles telling the stories of the Baptist, St. John the Evangelist and Mary, closed by an original frescoed polyptych: it is probably all attributable to one of the most talented painters of 14th-century Tuscany, Taddeo Gaddi, who left his works in Florence in Santa Croce, in San Miniato al Monte, and then again in the Monumental Cemetery in Pisa and in several other important buildings of worship in the region.

And it was the walls of this castle that, in the late nineteenth century, inspired the writer Emma Perodi, originally from another ancient feud of the Guidi family (Cerreto Guidi, in the Empolese area), author of several children’s books: her famous Novelle della nonna are all set in a fairy-tale Casentino, populated by knights, gentlewomen, fairies, saints and devils. And in this ancient and defiladed land, almost hidden from the rest of Tuscany, in the mystical and silent Casentino, one can still hear the distant echo of these stories.

|

| Francesco Morandini known as Poppi, Lamentation over the Dead Christ (c. 1580-1590; oil on canvas, 140 x 100 cm; Poppi, Prepositura di San Marco) |

|

| The castle of the Conti Guidi. Ph. Credit Michele Zaimbri |

|

| The Rilliana Library |

|

| A detail of the painted polyptych by T-addeo Gaddi |

Article written by the editors of Finestre sull’Arte for UnicoopFirenze’s “Toscana da scoprire” campaign

|

| Poppi, between hermitages and castles in the silent forests of Casentino |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.