If you say “Anghiari,” you invariably think of two things: the battle of 1440, and Leonardo da Vinci. And the two are connected, since the great Renaissance genius was supposed to have painted the Battle of Anghiari on the surface of one of the walls of what is now the Salone dei Cinquecento in the Palazzo Vecchio: as is well known, due to technical difficulties (the color began to run, perhaps due to incompatibility with the plaster as we infer from Paolo Giovio, and irreparably ruined the wall painting), Leonardo was unable to to complete his work, abandoned it, and several years later, when Florence found its political stability under the Medici, the walls were frescoed by Giorgio Vasari with scenes of victorious battles of the Florentines. Today, the moment of the Battle of Anghiari painted by Leonardo is known only through copies, such as the very famous Tavola Doria.

At Anghiari, too, the Florentines won: it was against the Milanese, who in those years were pursuing an aggressive expansionist policy that threatened to seriously damage Florence. The armies, having come into contact near the village, clashed in a relatively short battle, won by the Florentines, who were able to bring back a decisive success in stopping the Milanese aims in Tuscany and neighboring areas.

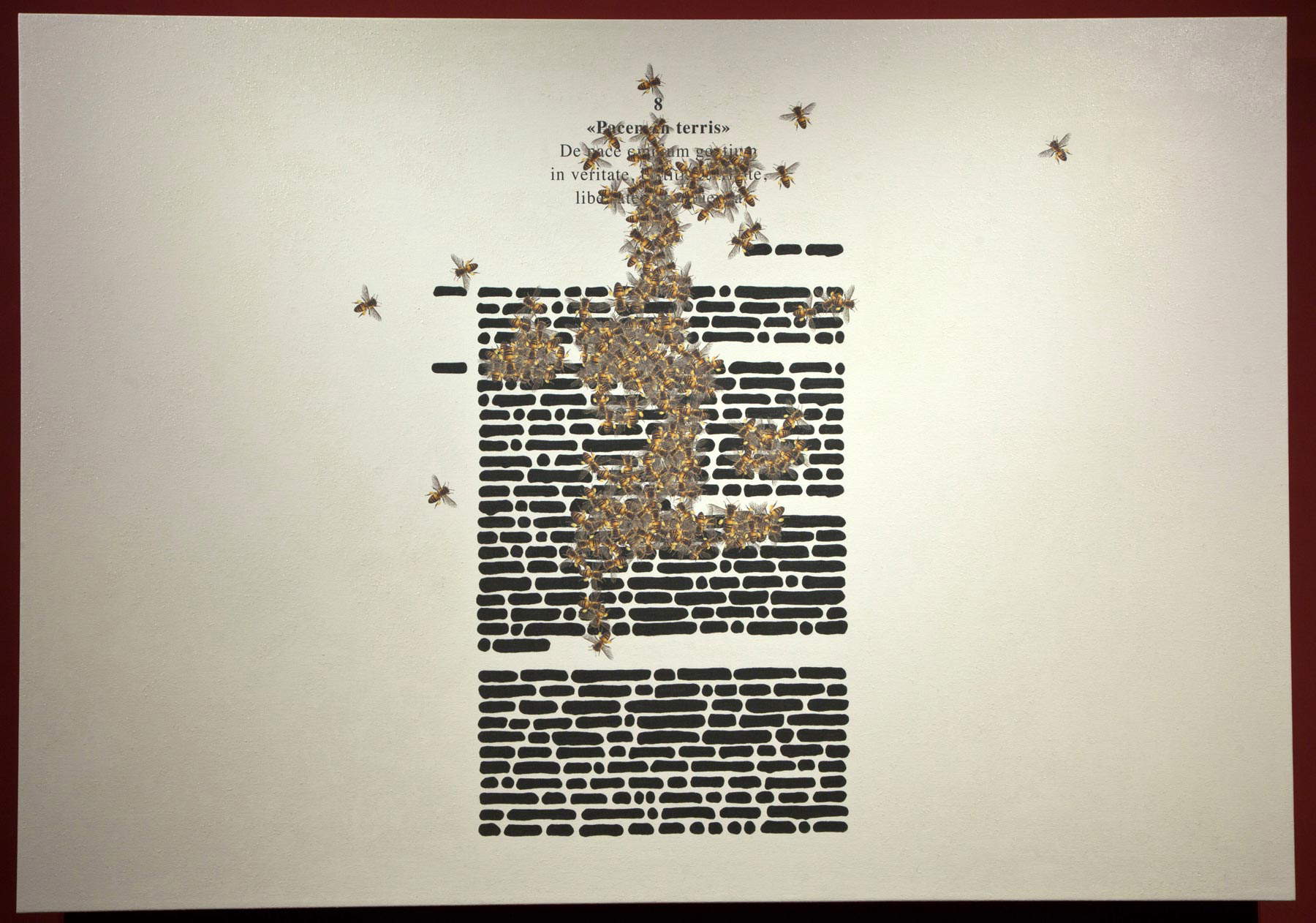

These events (including those in Leonardo’s mural) are today commemorated in the Museum of the Battle of Anghiari, housed in the Palazzo del Marzocco: it collects artifacts, ancient weapons, drawings, prints, reproductions of Leonardo’s lost work, and since last year also a significant work by Emilio Isgrò, Pacem in terris, created for the celebrations of Leonardo’s five-hundredth anniversary, a unicum in the artist’s production, since here Isgrò introduced the motif of bees, whose task is to suck the pollen from the words that the artist hides with his typical erasures.

|

| View of Anghiari |

|

| Francesco Morandini known as Poppi (?), Tavola Doria (1563?; oil on panel, 86 x 115 cm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries) |

|

| The Museum of the Battle of Anghiari |

|

| Emilio Isgrò, Pacem in terris (2019; mixed media on canvas, 140 x 200 cm) |

|

| A street in Anghiari |

Opposite the Museo della Battaglia, stands the town’s other museum, the Museo di Palazzo Taglieschi, devoted entirely to art: few people know it, but here is preserved a 1420 masterpiece by Jacopo della Quercia, a refined Madonna and Child that ranks among the most interesting sculptures to be seen in the Valtiberina (without detracting from Andrea della Robbia’s colorful Nativity , displayed not far away). And then, a rich selection of the Florentine seventeenth century, with many of its main protagonists-Jacopo Vignali, Matteo Rosselli, Giovanni Battista Ghidoni. There is also a bit of the sixteenth century, with Giovanni Antonio Sogliani, whom we also find with no less than two panels in the Chiesa delle Grazie, which also houses a couple of works by Puligo and a large glazed terracotta by Andrea della Robbia.

Anghiarians are said to have a strong character: after all, one only has to see what the village looks like to understand why, and also to understand why it was so strategic in the Renaissance, when it was, moreover, a borderland. Anghiari is perched on a hill, seeing everything from above, clinging as it is to its mighty ramparts that still partly survive today: even at a distance one can recognize the silhouettes of the buildings that most characterize its skyline, namely the soaring Campano Tower, 13th century but rebuilt in the 16th century after Vitellozzo Vitelli destroyed it in 1502, theimposing Rocca, which had the bizarre fate of having been first a fortress erected for defensive purposes, and then a monastery of Camaldolese monks (so much so that it is also known as “il Conventone”), and the bell tower of St. Augustine’s Church, the largest in the town.

Yet, one would not guess that such an austere village when viewed from afar and in the landscape, also harbors a gentle soul within. There are flowers everywhere, manicured gardens, cozy craft stores. And art everywhere, of course. Even in the streets: standing in Piazza del Popolo in front of the austere Palazzo Pretorio, with the typical myriad coats of arms of the vicars of the Florentine government who administered the village on its façade, you will notice a fresco decorating a niche: it is a 15th-century Madonna and Child with Saints. Inside, there is instead, again frescoed, a 15th-century allegory of justice, the author of which we do not know, but it is likely to be the work of Antonio di Anghiari, best known as the first master of Piero della Francesca, a native of these areas (he was from Sansepolcro). The church of Sant’Agostino, mentioned above, could be elected as an iconic symbol of the whole village and its capacity to surprise: the façade, fifteenth-century, is bare, sober, decorated only with a quiet portal and a small oculus. But inside here baroque splendor opens up, with 18th-century decorations that completely change the face of the building and the image we had had of it on the outside.

|

| The Museum of Palazzo Taglieschi |

|

| Jacopo della Quercia, Madonna and Child (1420; polychrome wooden sculpture, 150 x 67 x 55 cm; Anghiari, Museo di Palazzo Taglieschi). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| The Praetorian Palace |

|

| Antonio di Anghiari (?), Allegory of Justice (c. 1460; fresco; Anghiari, Palazzo Pretorio) |

|

| The church of Santo Stefano |

It should be noted that those seeking Tuscan conviviality cannot do without Anghiari: if there were a ranking that relates the number of inhabitants of a town to the amount of events held there, then Anghiari would perhaps be among the top places in the region. The traditional feast of St. Martin, the Anghiari Music Festival, the Palio held each year on June 29 in commemoration of the victory in the battle (the first edition was just the following year, 1441, and the palio lasted until 1827: after a nearly two-hundred-year hiatus, it started again in 2003), and the very famous “Tovaglia a quadri,” the townspeople’s very special dinner in the piazza, a kind of symbol of the way the Tuscans understand life: just a few of the many ways the townspeople have of partying.

Then, after the revelry is over, on the way down from the village one cannot help but stop at the very old church of Santo Stefano: it is one of the rare churches from the 7th-8th centuries that still exist in Tuscany today, a building therefore a thousand and three hundred years old, so old that we do not even know who founded it, perhaps the monks of San Colombano at the time of the Lombards. Apparently there was another one opposite reserved for Arian worship, and the church of St. Stephen may have been built there as if to put a stop to heretics. Already at that time, in short, battles were being fought in Anghiari.

Article written by the editorial staff of Finestre sull’Arte for UnicoopFirenze’s “Toscana da scoprire” campaign.

|

| Anghiari, the village of battle amid Renaissance masterpieces and street dining |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.