Vilhelm Hammershøi (Copenhagen, 1864 - 1916) is one of the most fascinating figures in European painting at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. Born in Copenhagen, he was one of the greatest Danish artists of his time and experimented with a wide variety of genres, devoting himself to portraits, landscapes, and, above all, the domestic interiors that made him famous. In 2025, for the first time in more than a hundred years that a selection of his works had not been seen in Italy, Palazzo Roverella in Rovigo gave the Italian public the chance to see an exhibition dedicated to him, Hammershøi and the Painters of Silence between Northern Europe and Italy, curated by Paolo Bolpagni (June 22 to June 29, 2025, here Ilaria Baratta’s review).

Hammershøi’s works are distinguished by a limited color palette, consisting mainly of grays, whites and earthy tones, and a minimalist composition that conveys a sense of stillness and introspection. Often, his paintings depict bare environments, illuminated by soft light, with female figures from behind, immersed in daily activities or simply in contemplation. This stylistic choice gives his works a suspended, almost dreamlike atmosphere that invites the viewer to silent reflection. Hammershøi was influenced by 17th-century Dutch masters such as Vermeer and de Hooch, as well as contemporary artists. However, he has developed a unique visual language characterized by a representation of reality filtered through a lens of austerity and mystery. His works do not tell explicit stories, but suggest emotions and moods through composition, light, and the absence of traditional narrative elements.

His paintings lend themselves to slow and concentrated observation. And to understand his art, it is necessary to trace his themes, methods and biography. Below are ten key points to orient yourself in Vilhelm Hammershøi’s poetic and suspended world.

Vilhelm Hammershøi showed an aptitude for drawing from an early age, which his mother Frederikke determinedly encouraged. By the age of eight he was already studying perspective and shadows under the tutelage of draftsman Niels Christian Kierkegaard. His father, more defiled in the artist’s biography, nonetheless contributed financial and emotional support. In letters to his brother Otto, Vilhelm gratefully recalls art-related Christmas gifts received from his parents and grandmother. This solid and cultured family environment was decisive for his education. His mother meticulously documented every stage of her son’s artistic growth, and in doing so left a valuable archive for posterity.

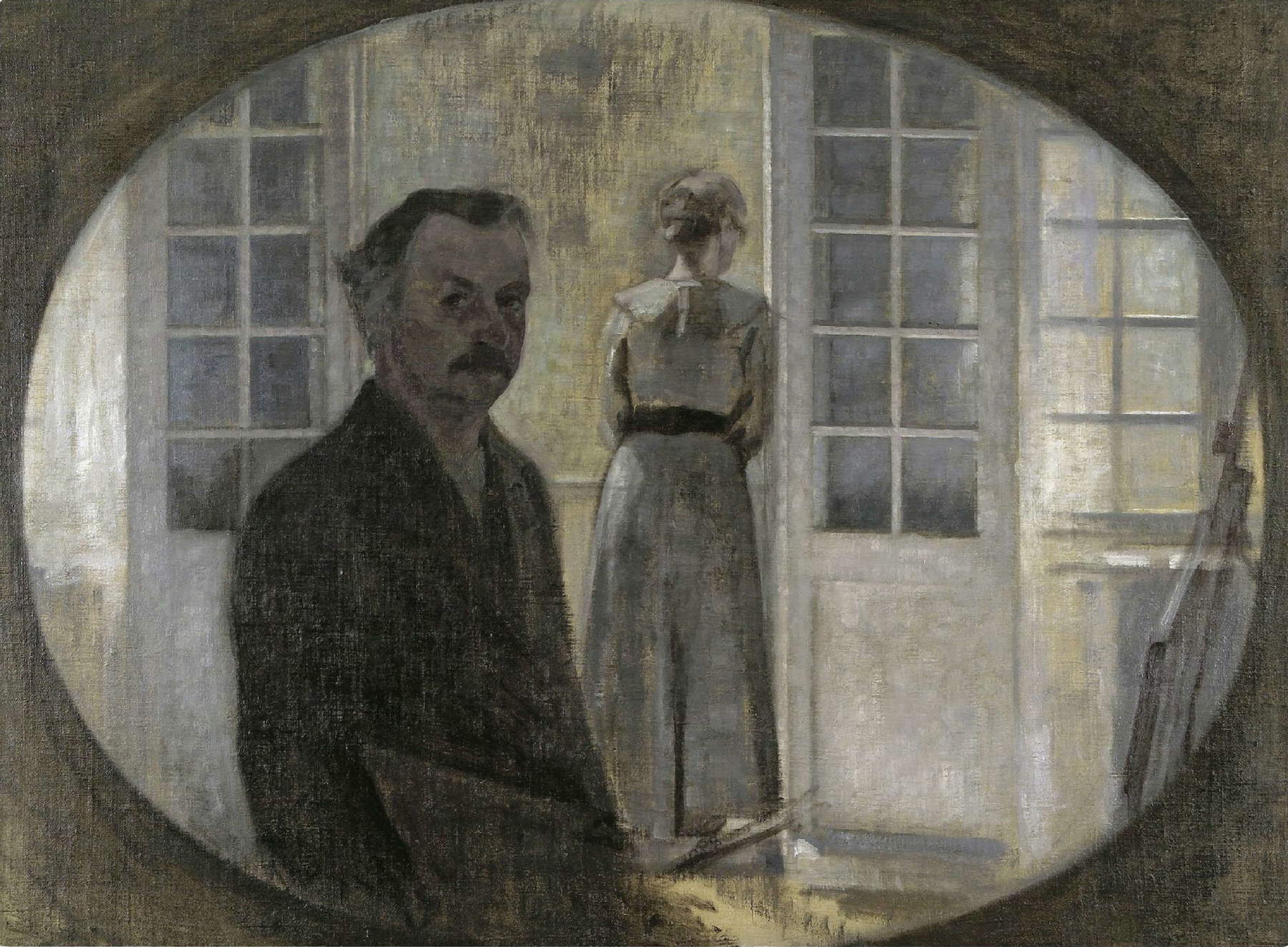

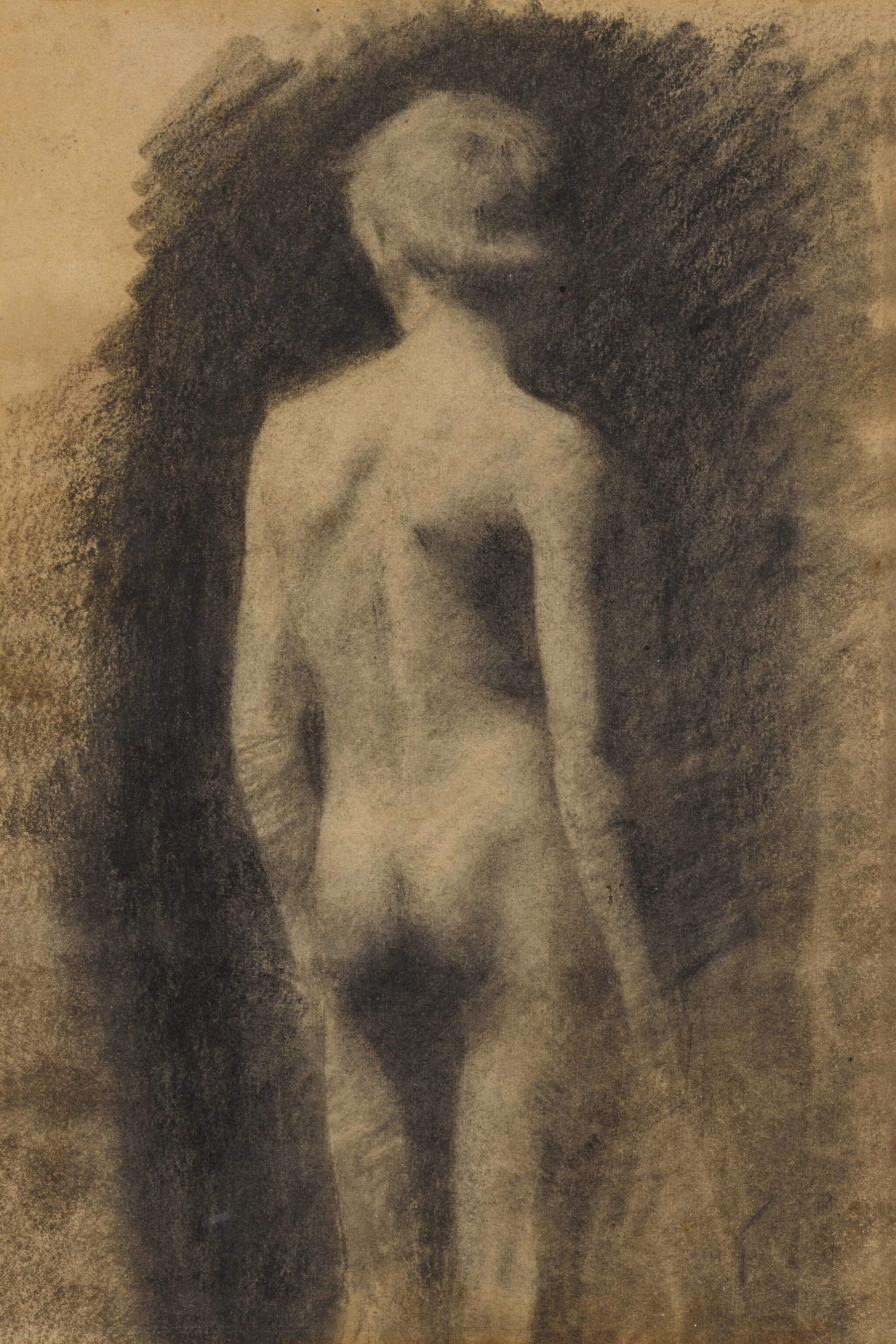

An early academic education, combined with an introverted and reflective character, forged the artist’s quiet and contemplative nature from early on. An introversion that would become a stylistic and human characteristic of his entire oeuvre. After private studies, Hammershøi attended the Kongelige Danske Kunstakademi (Royal Danish Academy of Art), followed by the Kunstnernes Frie Studieskoler (Independent Study School for Artists), where he was a student of Peder Severin Krøyer. The academic environment provided him with a solid foundation: anatomy, study from life, skillful use of light. One of his earliest works, Study of a Male Nude Seen from Behind, on display in Rovigo, already shows his interest in bodies immersed in shadow, emerging from the half-light. But what distinguishes him from other students is the immediacy with which he begins to develop a personal style. For while many of his peers were moving toward a direct naturalism, Hammershøi chose inner investigation. Academic training becomes a starting point for him, not an end point: his art soon takes its own, quiet, collected, utterly recognizable path.

Hammershøi’s work is part of a painting tradition that finds in the Dutch school of the seventeenth century one of its most important references. The influence of painters such as Johannes Vermeer, Pieter de Hooch, Gerard ter Borch, Samuel van Hoogstraten, Gabriel Metsu, Nicolaes Maes and several others can be seen especially in the use of light, the composition of domestic interiors and the depiction of everyday life through minimal gestures.

“These are painters,” wrote Paolo Bolpagni, “characterized by an intimist approach, rather restrained colors, and the choice of subjects that will be those of Hammershøi: sharp, bare architecture (this is especially the case in Saenredam), doors and windows through which a clear light enters, domestic interiors tacit and calm, often devoid of human presence, or with women depicted from behind as they sew, read, play the virginal or sweep the floor.”

Like Vermeer, Hammershøi shows a deep attention to natural light, which enters through a side window and defines the scene with great delicacy. But while Vermeer often uses color to enliven the composition and tell intimate stories, Hammershøi reduces its impact, choosing a chromatic restraint that accentuates emotional distance. More generally, from seventeenth-century Dutch painting, Hammershøi instead inherits the use of domestic space as a site for representing ordinary reality. However, Hammershøi’s paintings lack that explicit narrative: his rooms do not recount familiar episodes, but convey states of mind.

Hammershøi is often referred to as “the painter of silence”(read an in-depth discussion by Ilaria Baratta here) because of his ability to convey, through his works, a profound sense of stillness and introspection. His bare and uncluttered domestic interiors are imbued with an atmosphere of suspended calm, where every element seems to be in its place and contributes to a meditative ambience. The choice to depict human figures from behind or immersed in solitary activities accentuates this feeling of isolation and contemplation.

Light plays a key role in his compositions, filtering gently through the windows and illuminating the rooms with a soft, diffuse luminosity. This use of light not only defines the space, but also contributes to an ethereal and timeless atmosphere. The lack of explicit narrative or symbolic details invites the viewer to project their own emotions and reflections into the work, making each painting a personal and unique experience.

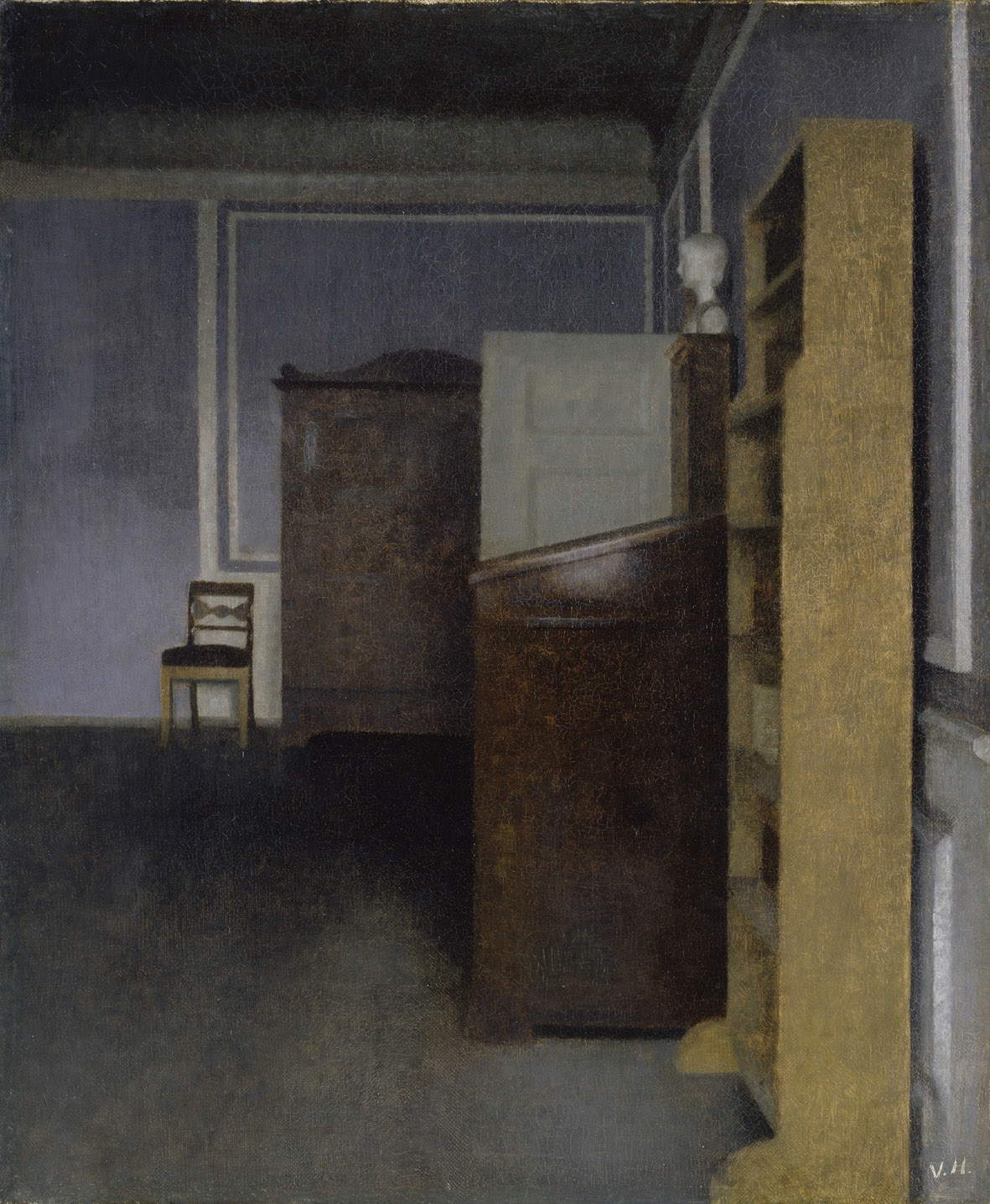

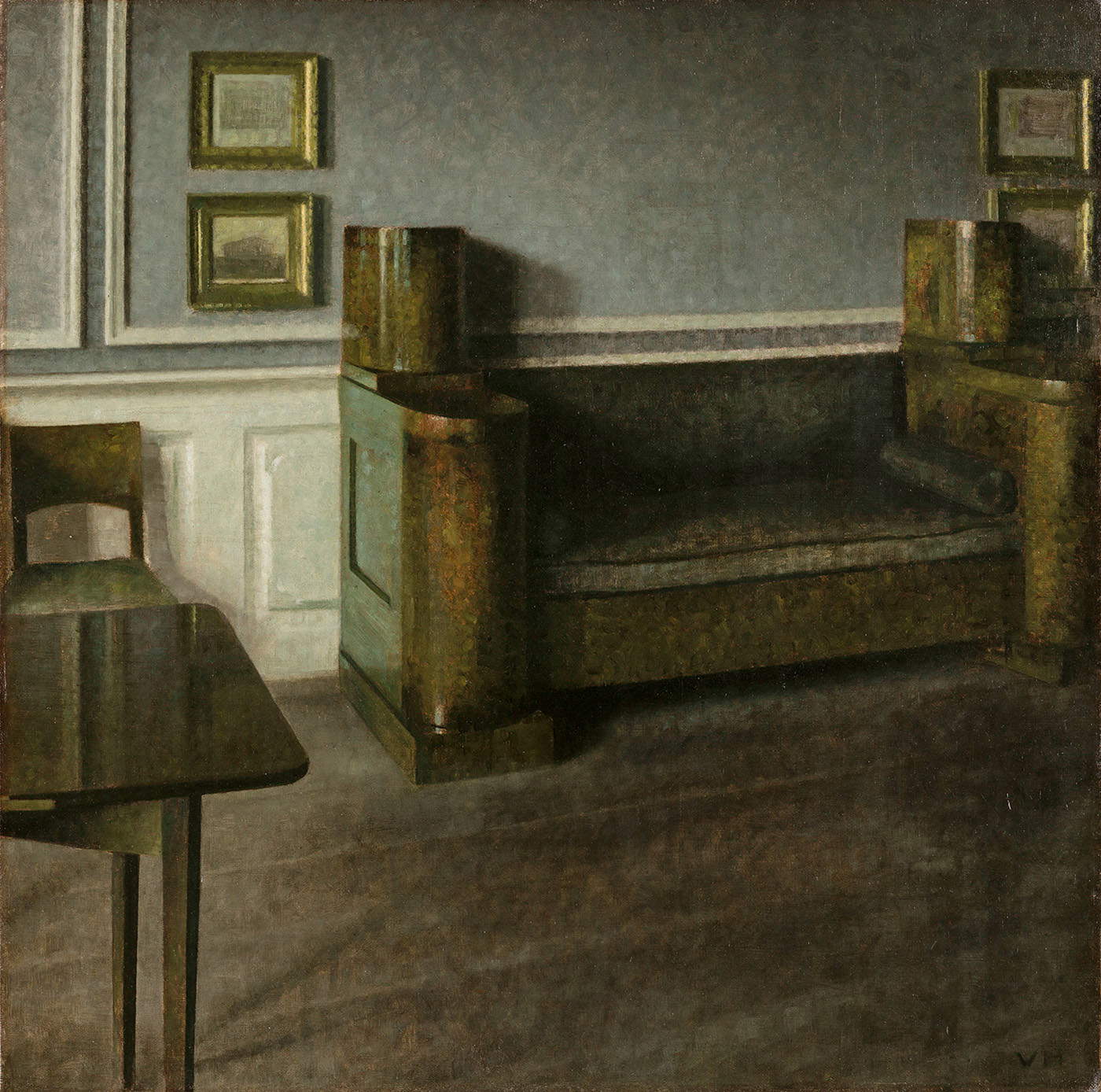

Hammershøi’s apartment at 30 Strandgade in Copenhagen’s Christianshavn district was the main subject of many of his most famous works. Living there with his wife Ida from 1898 to 1909, this domestic space became the ideal stage for exploring themes of loneliness, introspection and beauty in the ordinary.

The rooms, furnished in a minimalist manner and painted in light, neutral tones, offered an ideal environment for experimenting with natural light and geometric compositions. Hammershøi often depicted the same rooms from different angles or with minimal variations, such as a door opened or closed, a chair moved or an object added, and in doing so he was able to create several variations on the theme, emphasizing stillness and repetition.

Hammershøi composes rooms as stage sets: his paintings, “depicting corners, walls and windows of their home from different perspectives and under different lighting conditions,” wrote scholar Annette Rosenvoldt Hvidt, “have become true icons, inspiring artists, filmmakers, writers and architects. Hammershøi adopts a method similar to that of a set designer, setting up the rooms of the house he intends to paint. In the course of this process, he adds or removes figures, furniture and objects, and often cuts out the image by folding part of the canvas back: in this way, he is able to create his own version of the interior, achieving exactly the desired image. For the same reason, he often omits certain details, such as door handles, cuts out furniture, and frames reality at an all-personal angle, enlarging certain phenomena and manipulating what he sees to create an absolutely individual image.”

Strandgade 30 is not just a physical place, but becomes a symbol of Hammershøi’s artistic research, a microcosm through which to explore universal themes of time, space and perception.

Ida Ilsted, sister of painter Peter Ilsted, a friend of Hammershøi, married Vilhelm in 1891. And she became a central figure in his work: she appears in numerous paintings, often depicted from behind or immersed in everyday activities. Her discreet and silent presence contributes to the atmosphere of introspection and mystery that characterizes the artist’s works.

The collaboration between Vilhelm and Ida reflects a deep artistic and personalunderstanding, in which mutual trust and understanding allow them to explore complex themes through the apparent simplicity of the scenes depicted. It is not easy to explain the relationship between the two: “ One might think of her as a muse,” Rosenvoldt Hvidt wrote, “but this concept is not sufficient to describe her role and the complexity of her relationship with Vilhelm. Ida is an essential part of the artist’s life and work: in addition to accompanying him on all his travels, she helps him find suitable places to live and paint, and she is the one who provides him with the peace of mind he needs to concentrate on his work, taking care of his extensive correspondence while they are on vacation or traveling, among other things. As far as we know, Ida left no direct accounts, so the information we have about her is conjecture and interpretation based on Vilhelm’s letters and photographs.”

Her expression in the portraits is absorbed, enigmatic, almost emblematic of Hammershøi poetics. In the most difficult moments, even marked by mental problems, Ida remained at the artist’s side, protecting the inner space that was her art. Far, then, from the stereotype of the passive muse she was, if you will, a silent co-author of an entire aesthetic universe.

Light is a fundamental element in Hammershøi’s work, not only as a tool to define forms and spaces, but as a silent protagonist that lends atmosphere and meaning to the scenes depicted. Nordic light, characterized by diffuse and soft luminosity, filters through windows and is reflected on surfaces, creating plays of shadows and shades that add depth and mystery.

Hammershøi uses light to emphasize the architectural structure of interiors, highlighting lines, angles and surfaces. Light thus becomes a means of exploring the geometry of space and creating a sense of order and harmony. At the same time, light helps create an atmosphere of stillness and contemplation, inviting the viewer to immerse himself in the scene and reflect on the meaning hidden behind the apparent simplicity.

In some works, light is the only dynamic element, suggesting the passage of time and the presence of an external reality beyond the domestic walls. This subtle and poetic use of light is one of the distinguishing characteristics of Hammershøi’s art, placing him among the great masters of the representation of light.

One of the most distinctive features of Hammershøi’s work is his use of a limited color palette, dominated by shades of gray, white, beige and occasional hints of color. This aesthetic choice gives his works an understated and refined appearance, emphasizing form, composition, and light rather than color.

The use of gray is not only a stylistic choice, but also a symbolic one. Gray, a neutral color par excellence, represents balance, calm and reflection. In Hammershøi’s works, gray contributes to an atmosphere of introspection and silence, in which every element is reduced to its essentials.

Yet despite appearances, Hammershøi’s paintings are built on a highly sophisticated palette. Whites are made of transparencies and opacities; grays contain blue or green highlights; blacks are intensified with pigments such as cobalt blue. The results of scientific analysis conducted by the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen show that the artist used a few colors with extreme precision. His approach to color is almost musical: minimal variations, but very rich in resonance. Looking at his canvases at length, one catches a subtle chromatic vibrancy that contributes to the sense of suspension. The pictorial material itself seems animated, as if it were breathing. Hammershøi paints not just objects or people, but the air around them.

Vilhelm Hammershøi made an element often considered marginal in traditional painting the protagonist of his works: empty space. In his interiors, walls, ajar doors, corridors, and communicating rooms do not just serve as backgrounds, but become active subjects, elements charged with emotional tension. Indeed, architecture is never simply functional: it is the true theater of sensory and psychological experience.

Hammershøi often paints empty or nearly empty rooms, where human absence is as eloquent as presence. His compositions are based on a strict geometry of vertical and horizontal lines, sequential doors, and windows that frame light. The effect is almost metaphysical: a sense of depth that seems to open up not only physical but also emotional perspectives.

One can clearly sense, in Hammershøi’s works, the influence of photography, although his art does not merely imitate it. His shots have a sharp, almost cinematic edge, with unexpected glimpses and off-center shots that break symmetry. It is not uncommon for the main subject to be partially cut off, or for the eye to be led to empty corners. Hammershøi knew and practiced photography-Ida herself took photographs-and this technical awareness is reflected in her paintings. But what makes her images unique is the use of this photographic grammar to construct a highly poetic painting. The partial blurs, the natural lighting, the absence of classical depth: all contribute to a feeling of still time, of waiting.

One of the most fascinating features of Hammershøi’s work is repetition. He paints the same corner, the same window, the same figure over and over again. Not for lack of ideas, but to explore the infinite variations of perception. Each painting is a variation on a theme: changing the light, the time of day, the arrangement of objects.

This seriality reflects an almost musical tension, similar to Bach’s variations or Monet’s cycles. It is also a way of exploring subjectivity: reality does not change, but our gaze does. Hammershøi seems to suggest that true creativity lies in deeply observing what is familiar to us. His method is both rigorous and meditative: through repetition, the ordinary becomes extraordinary. His art, like a visual mantra, invites us to see beyond appearance.

While Europe at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was being traversed by turbulent and experimental artistic currents such as Impressionism, Symbolism and the early avant-garde, Hammershøi remained seemingly defenseless, uninvolved in fashions. And after his passing, his art soon fell into oblivion. “The problem,” Bolpagni wrote, "is that Hammershøi is not pigeonholeable, he escapes classification, because he is neither modernist nor anti-modernist, and we know how prevalent are the methodologies that start from theory, in short from a critical or philosophical or hermeneutical or ideological assumption, and try to adapt the phenomenology of artistic facts and products to it, instead of proceeding the other way around, as would be right. Let us also add, somewhat provocatively, that our Hammershøi also has the ’defect’ of being European, Western, bourgeois, born to a well-to-do, indeed affluent family, the grandson of a shipowner: a privileged man, moreover from a colonial country (let us hope that the woke ideology does not end up harming him)."

However, his choice to remain secluded was in itself profoundly modern. Hammershøi’s modernity is not one of painterly gesture, formal rupture or technical innovation. It is a modernity of the gaze, of interiority. His paintings may seem conservative, but they hold a silent revolution: the idea that art can reduce everything to the essential in order to find truth and authenticity. In his focus on solitude, on elusive identity, on the imperceptible passage of time, Hammershøi anticipates certain existentialist sensibilities of the 20th century. His paintings tell nothing, but make one perceive everything: emptiness, expectation, the absolute in the everyday.

This form of modernity makes him a surprisingly relevant artist, still able to speak to a viewer accustomed to noise but in search of silence and depth. Therein lies the true strength of his legacy: in his ability to speak to every generation, for in the silent contemplation of his figures, in the shadows of his rooms, everyone can find something of himself.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.