They first met in Venice in the spring of 1819 in the drawing room of Countess Benzoni, one of the ladies who very often held receptions or simple “conversations” in her wealthy residence, and who was known at the time as the “Biondina in gondoletta” to whom a song had been dedicated in the city. And it was immediately love at first sight between George Gordon Lord Byron and Teresa Gamba Guiccioli.

Lord Byron (London, 1788 - Missolonghi, 1824) is one of the most significant English Romantic poets of the early 19th century, author of the famous narrative poem in four cantos Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, published between 1812 and 1818. The first two cantos of the poem were inspired by his journey through Europe, thanks to which the figure of the lonely and melancholy vagabond traveler, the poem’s protagonist, became widespread. He wrote the third canto influenced by the Swiss social and cultural scene, which he encountered during his stay in Switzerland in the company of Percy Bysshe Shelley (Horsham, 1792 - Lerici, 1822) and Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin (London, 1797 - 1851), while the fourth and last canto of his long poem was composed in 1817, when Byron was in Venice; here he also composed the comic-satirical poem Beppo (1818), influenced by the Italian Luigi Pulci (Florence, 1432 - Padua, 1484), and the first cantos of another of his masterpieces: Don Juan (1818-1822).

He also had a reputation as a ladies’ man: notoriously handsome and charming, he used to seduce numerous maidens. After his unsuccessful marriage to Anna Isabella Milbanke, married mainly for financial reasons, and his love affair with his half-sister, Augusta Leigh, which caused quite a stir in public opinion, the Romantic poet was forced to leave England forever around 1816, first for Switzerland, then Italy. As a father he was a disaster: he had a legitimate daughter, Ada, with whom he established no relationship, as they hardly ever dated, and a child born of one of his conquests around Europe. This illegitimate daughter was entrusted to the education of the Capuchin nuns of Bagnacavallo. It is said that ill, in serious condition, the little girl at the age of five wrote a tearful letter to her father asking to see him again at least once, but he was unmoved and did not fulfill his daughter’s last wish, despite being in nearby Pisa.

Teresa Gamba Guiccioli (Ravenna, 1799/1800 - Florence, 1873) was a countess from Ravenna, daughter of Count Ruggero Gamba. The latter arranged the marriage between his very young daughter, then 18 years old, and Alessandro Guiccioli, a member of the Ravenna nobility now almost 60 years old, a widower with a reputation for being libertine, miserly, but ready to engage in stratagems to obtain investments and favors.

|

| Thomas Phillips, Portrait of Lord Byron (1813; oil on canvas, 91 x 71 cm; Newstead, Newstead Abbey) |

|

| Giuseppe Fagnani, Portrait of Teresa Gamba Guiccioli (1859; oil on canvas; Private collection) |

Only a few months had passed since their marriage when Lord Byron and Teresa Gamba first saw each other at that “conversation” in the Benzoni house in April 1819. On that occasion, Countess Benzoni asked the poet if he wished to meet and get to know the young Countess Gamba, who had arrived in the drawing room with her husband; at first he refused, adding that he did not wish to meet any woman, either beautiful or ugly. However, as a result of the landlady’s insistence, he was introduced to Teresa as a “Peer of the English Kingdom and a great poet.” The latter was immediately captivated by his melodious voice and smile, as well as his heavenly appearance, as she wrote in her Vie de Lord Byron en Italie, a text drafted after the poet’s death. Teresa, at their first meeting, was three months pregnant and mourning the passing of her mother and one of her sisters.

Frequent dinner and theater dates followed, until one evening Byron proposed that she come to him by gondola, which would arrive at a certain time; afterwards they would go together to the Casino of Santa Maria Zobenigo. In a letter to his friend Lord Kinnaird, the romantic poet described his beloved as “beautiful as the dawn and warm as noon.”

Teresa’s husband, Alessandro Guiccioli, was also aware of these passionate dates and their love affair, and he sent her back to Ravenna. There, stricken by lovesickness and hospitalized for an abortion, the young woman never left his bed, until he had Lord Byron rush in, even hosting him in his Ravenna palace. This fact confirmed, in front of everyone, that the poet had become Teresa’s “cavalier servente,” that is, lover: amorous encounters between the two were revealed by some spies; moreover, anonymous letters reached her husband and sarcastic tunes were frequently addressed to him as he passed on the street, because of his betrayed status. However, presumably Guiccioli accepted and covered for the two lovers for economic reasons, hoping to gain by an exchange of favors, as can be deduced from the singular request to his wife’s lover for money loans, but Byron refused. With her father’s support, Teresa petitioned the pope for separation from her husband on the grounds of serious insults and obscenities; Guiccioli defended himself by reasoning with his wife’s unfaithful attitudes, but the pope granted the separation on the condition that she live with her father.

As time passed, the overwhelming romance between Byron and Teresa became mostly almost a marital affair, and perhaps it was also for this reason that the poet sought a diversion to leave and thus avoid the boredom of married life.

Already in the course of their relationship, Byron had approached Carboneria through Teresa’s brother Pietro, who joined the cause with such ardor that in 1821 the whole family was forced to leave Ravenna and move to Pisa, and the poet followed them. It is said that he arrived in the Tuscan city with seven servants, five cars, nine horses, a monkey, two mastiffs, two cats, three peacocks, some chickens, a considerable library and a large amount of furniture. The revolutionary spirit that had accompanied Byron in those years did not stop, so when a strong cause presented itself to him to fight for, he wanted at all costs to leave to make his contribution. It was the struggle for the liberation of Greece from Turkish oppression. Teresa would have been left alone, without her great love, but Lord Byron, wishing to feel “alive” again after his rather quiet Italian period both socially and sentimentally, left Livorno in July 1823 to head for Hellenic territory. Unfortunately, however, it was in Greece that he found death: he fell ill and died in Missolonghi the following year, at the age of thirty-six.

|

| Giacomo Trecourt, Lord Byron on the Shores of the Hellenic Sea (c. 1850; oil on canvas, 153 x 114.5 cm; Pavia, Musei Civici) |

|

| Ludovico Lipparini, The Oath of Lord Byron on the Tomb of Markos Botsaris at Missolungi (1850; oil on canvas, 250 x 350 cm; Treviso, Museo Civico) |

Teresa despaired over the tragic event, but nevertheless decided to write Vie de Lord Byron en Italie, a biography in French about the man she had deeply loved and would love forever, although after the poet’s death, the young woman remarried another man, becoming the Marquise de Boissy. The biography was never published, as she kept the long manuscript, along with some of her beloved’s personal belongings, hidden for herself: today it is all kept at the Classense Library in Ravenna.

In 1833 the poet Alfred du Musset came to Venice to follow in Byron’s footsteps and, referring to the love affair between Byron and the countess, wrote: "Blond cheveaux, sourcils bruns, front vermeil ou pâli; Dante amait Béatrix - Byron la Guiccioli,“ or ”Blond hair, brown eyebrows, rubicund or pale forehead; Dante loved Beatrice - Byron la Guiccioli." Indeed, Teresa is described in various accounts as a beautiful girl with long blond hair, endowed with great feeling and a very sweet and gentle character.

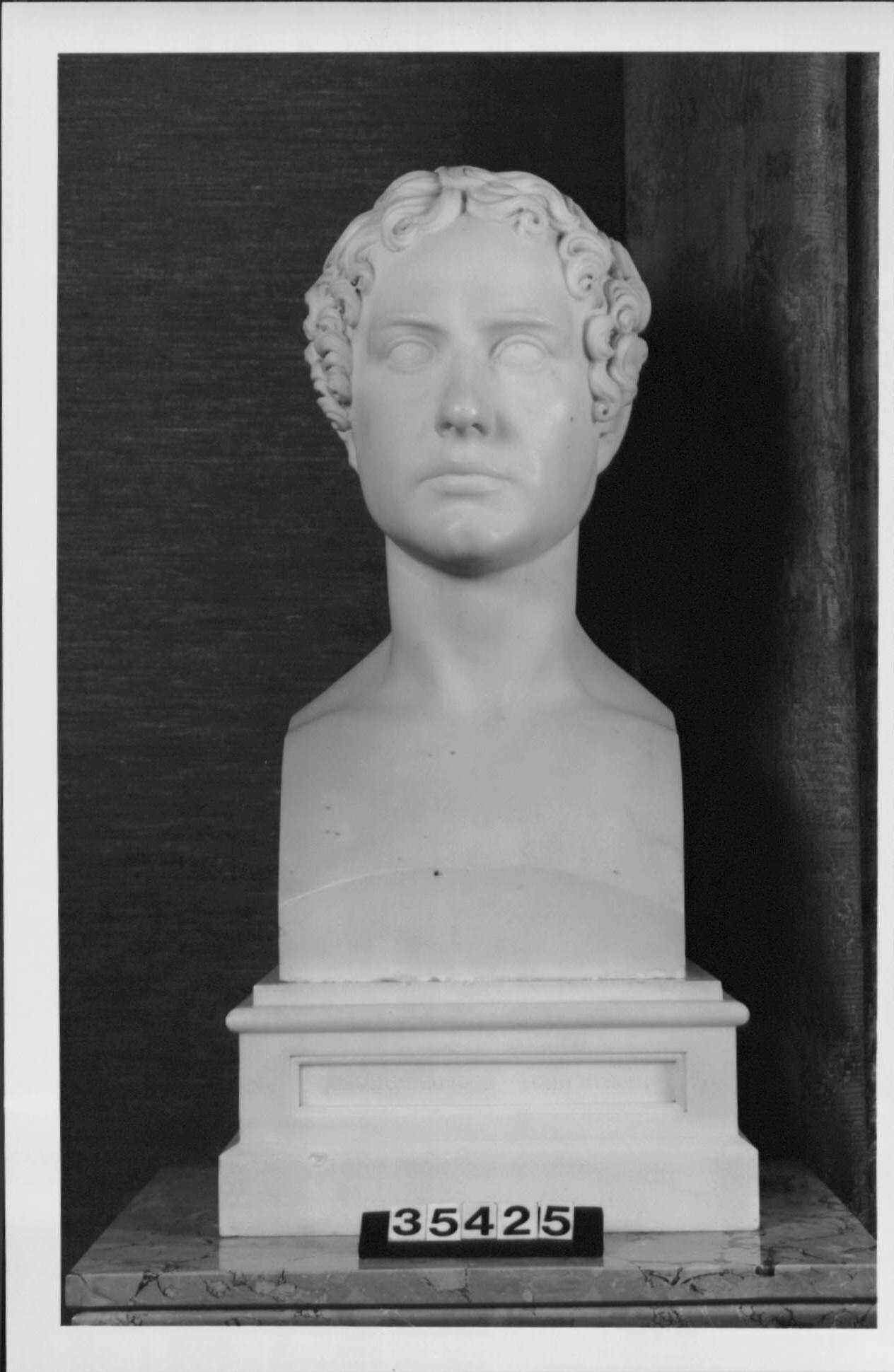

We can get an idea of the appearance of Lord Byron and Teresa Gamba by admiring two works depicting them: two sculptures, or rather two marble busts, depicting the poet and the countess made by two of the greatest artists active at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries. The first was depicted by Bertel Thorvaldsen (Copenhagen, 1770 - 1844), considered one of the greatest exponents of Neoclassicism: the artist made two models for the bust of George Gordon Lord Byron between 1817 and 1833. The second is preserved today in Italy, at the Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan.

In May 1817 Lord Byron visited Thorvaldsen’s atelier, following a letter from John Cam Hobhouse, in which the latter expressed to the artist his desire to see the greatest English poet of the time represented. Suddenly entering the sculptor’s studio, Byron, wrapped in a large cloak, asked to have his bust executed. The two had an immediate misunderstanding: Thorvaldsen was convinced that the poet had assumed an unnatural expression, even grimacing, but he abruptly replied that that was his true expression. As a result, the sculptor portrayed him following his own vision of the model, and when the work was finished, the poet protested as he believed the bust did not resemble him at all, making him look much sadder. He actually liked the sculpture and wrote in a letter to his editor John Murray that the work had won general approval. Moreover, Hobhouse wrote that the likeness was perfect and the artist had worked with love.

The one preserved at the Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana is one of the specimens executed after the poet’s death following a second model (the first is now preserved at Windsor Castle), different from the first only in the shape of the old-fashioned draped bust, more suitable for monumental heroic sculpture. There is a strong balance between natural and ideal depiction in the sculpture: it is a composed, frontal, hieratic portrait that harks back to classical antiquity; the naturalistic datum is found in the frowning eyebrows and lobe-less ears, which Byron was proud of as a sign of nobility.

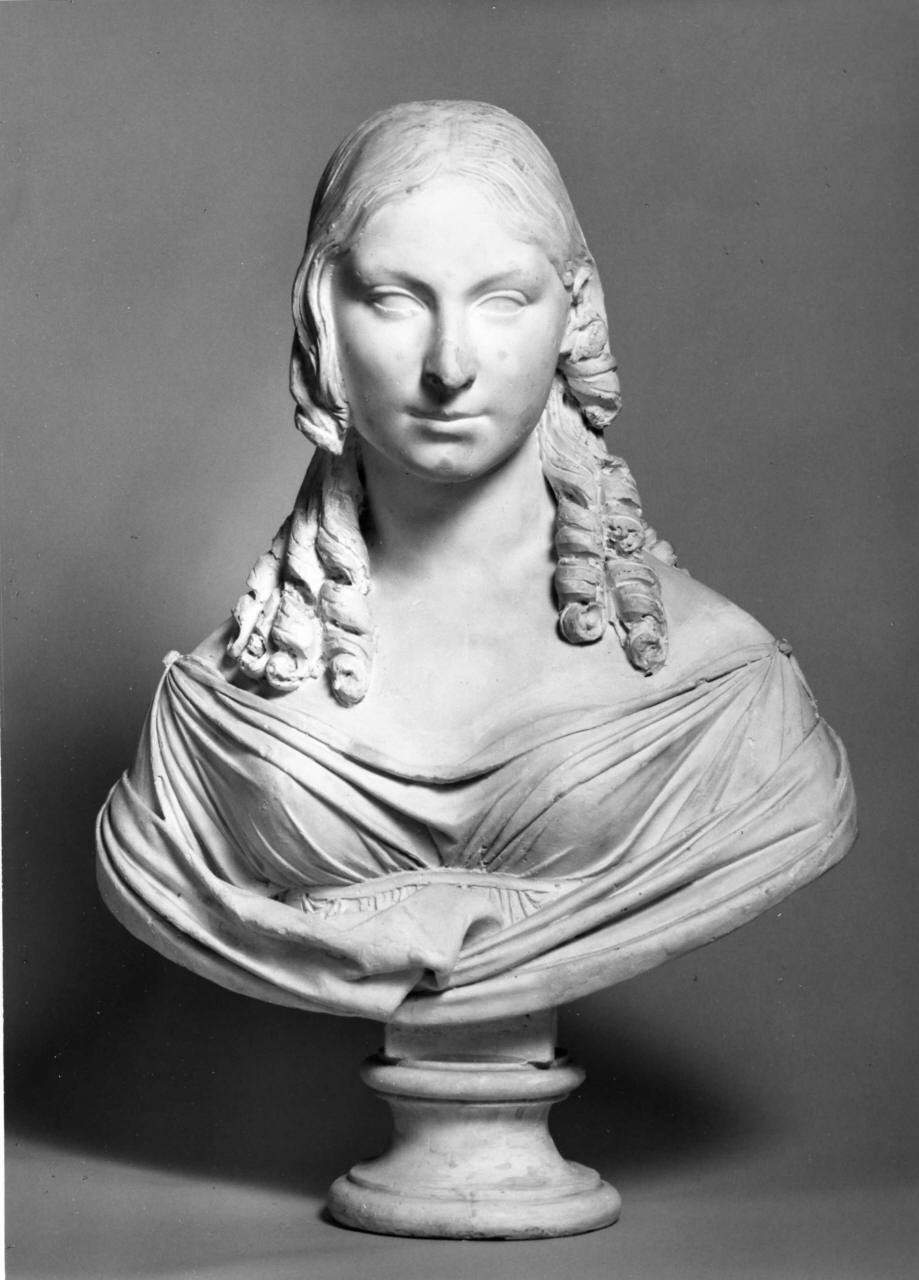

But evidently the portrait executed by Thorvaldsen was not enough for him. In fact, on March 6, 1822, when the poet was residing in Pisa, he wrote in a letter addressed to John Murray that Lorenzo Bartolini (Savignano di Prato, 1777 - Florence, 1850), a celebrated sculptor, wished to portray him in a bust and that he agreed on the condition that he also portray Countess Guiccioli. He made both, but, in his opinion, the one depicting Teresa was more beautiful. The sculptor from Prato began his rehearsals many times, and when he finished the bust of Lord Byron on January 4, 1822, the poet told him, in Tuscan, “La è la ultima volta che mi son son farsi ritrarre.”

The marble bust of Countess Teresa Gamba Guiccioli made by Lorenzo Bartolini in 1822 is now preserved in the Classense Library in Ravenna thanks to a donation by descendants of the Gamba family made in 1949. It was previously in the villa in Settimello, near Florence, which was purchased by Teresa and her husband Hilaire Ronillé, Marquis of Boissy. Instead, the original plaster model is kept in the Museo di Palazzo Pretorio in Prato.

|

| Bertel Thorvaldsen, Bust-Portrait of Lord Byron (1817; marble, 60 x 29.3 x 22.2 cm; Windsor, Royal Collections) |

|

| Bertel Thorvaldsen, Bust-portrait of Lord Byron (1817-1833; marble, 69 x 48 30 cm; Milan, Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana) |

|

| Lorenzo Bartolini, Bust-portrait of Lord Byron (1822; marble, 47 x 32 x 26 cm; Florence, Galleria d’Arte Moderna di Palazzo Pitti) |

|

| Lorenzo Bartolini, Bust-portrait of Teresa Gamba Guiccioli (1821; marble, 49 x 66 cm; Ravenna, Classense Library) |

|

| Lorenzo Bartolini, Bust-portrait of Teresa Gamba Guiccioli, plaster model (1821; plaster, height 70 cm; Prato, Museo Civico di Palazzo Pretorio) |

|

| The busts of Teresa Gamba Guiccioli (Bartolini, Classense) and Lord Byron (Thorvaldsen, Ambrosiana) together on the occasion of the 2017-2018 Canova, Hayez, and Cicognara exhibition |

The bust portrays Countess Gamba Guiccioli frontally with delicate and refined features. She sketches a slight smile and her extraordinary beauty is well perceived. Her hairstyle also denotes a certain elegance: long, flowing hair falls over her shoulders, with ringlets at the tips. Her cleavage is concealed beneath a richly pleated robe. Again, as in the bust of Lord Byron made by Thorvaldsen, the natural component binds with the ideal one, creating a sculpture that harks back in form to classical antiquity, but allows expressive features to shine through. The solemn gentleness in Teresa’s face also recalls a renewed interest in the tradition of Verrocchio (Florence, c. 1435 - Venice, 1488), a 15th-century artist who in his often refined and delicate works was able to combine dynamism and naturalism.

The two busts portraying Lord Byron and Countess Teresa Gamba, by Thorvaldsen and Bartolini respectively, should be admired side by side, as really studied and proposed in the exhibition Canova, Hayez and Cicognara. The Last Glory of Venice that was held in the Galleries of Venice between 2017 and 2018, on the occasion of the bicentennial of the Galleries. This is because they would place next to each other works made in roughly the same years by great artists, who were fortunate enough to portray from life two of the most fashionable figures of that era linked by a love affair and with a story to tell. A story that even today, through the works mentioned, could continue to be told.

Reference bibliography

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.