The image of the so-called Self-Portrait by Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519), the most famous work among those preserved in the Royal Library of Turin, is certainly one of the most familiar to the public, as well as, in all likelihood, the best-known drawing by the great Da Vinci, a sheet whose fame is matched only by that of theVitruvian Man preserved in the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice. In fact, the debate over the identity of the subject is still open: there are those who consider it really a self-portrait of the Tuscan genius, tested by a career all devoted to art and work and therefore looking much older than the sixty-seven years Leonardo was when he disappeared (we know that to the canon Antonio de Beatis, who met him at the château of Clos-Lucé in 1517, the artist made the impression of a “veghio de più di LXX anni”), those who believe it is a preparatory drawing for the Last Supper, and those on the contrary who think it is an ideal face of a philosopher, a hypothesis the latter of which has gained wide acceptance in recent years.

Despite its celebrity, theSelf-Portrait is not the only work by Leonardo da Vinci kept by the Royal Library of Turin: in fact, the Piedmontese institution preserves as many as thirteen drawings by the artist from Vinci, and one of his precious manuscripts, the Codex on the Flight of Birds. Why so many works by Leonardo at the Turin library? The first leap back in time takes us to July 1840, that is, the first time the Leonardo nucleus is mentioned: writer and journalist Davide Bertolotti, in his Description of Turin, informs the reader that “the King’s Particular Library is full of the choicest and most beautiful modern editions of works belonging to history, travel, the arts, public economy, and various sciences. It contains more than 30,000 printed volumes, among them some in parchment and illuminated [...]. There is particularly a collection of about 2,000 ancient drawings, among them 20 by Leonardo da Vinci, and others by Raphael, Correggio, and Titian.”

It is necessary, however, to go back a few months earlier to know the circumstances under which Leonardo’s drawings became the property of the library. The protagonist of the story is a renowned connoisseur, Giovanni Volpato (Riva presso Chieri, 1797 - Turin, 1871), who after receiving art training in Turin moved to France to pursue a successful career as an art dealer and also to start his own collection. Returning from Paris in 1837, Volpato became Accounting Secretary of the Academy of Fine Arts in Turin: shortly before he had met the engraver and connoisseur Giovanni Battista De Gubernatis (Turin, 1774 - 1837), to whom he had shown his own collection of drawings in 1836. It was the first time drawings from Volpato’s collection were shown in Turin, where he wished to sell them. He would succeed in doing so in 1839: this was the year in which his collection was purchased almost in its entirety, at a price, moreover, greatly reduced from the initial request, by King Charles Albert, after a negotiation that lasted almost three years. Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings, in all likelihood, were part of the nucleus of works sold by Volpato to the ruler. However, scholar Maria Luisa Ricci has written, “what bound the Chierese connoisseur to his collection of drawings was something deeper than the understandable pleasure of possession and transcended the simple business sense: Volpato, in fact, reserved the right to continue managing, handling, organizing, and restoring the drawings that had just been sold, and it cannot be ruled out that these claims played an important role in the negotiations and influenced, in all likelihood, the lowering of the final sale price.” It was Volpato himself, moreover, who arranged the drawings for the Royal Library, also personally taking care of the gold backing cards, still used today for many of the institution’s works. We do not know for what reasons the king had decided to purchase Volpato’s collection, and whether he had known about the presence of Leonardo’s drawings, or whether on the contrary it was just a great stroke of luck: what is certain, is that in 1847, the art historian Amico Ricci, observing the drawings in the Royal Library wrote that the king, “turning to England, found a portfolio of some drawings by Leonardo da Vinci, which win as much as others of his in finesse, intelligence and choice of compositions.” This testimony, given also Ricci’s relationship with the first director of the Royal Library, Domenico Promis, might support the fact that Carlo Alberto had given a specific mandate to Giovanni Volpato.

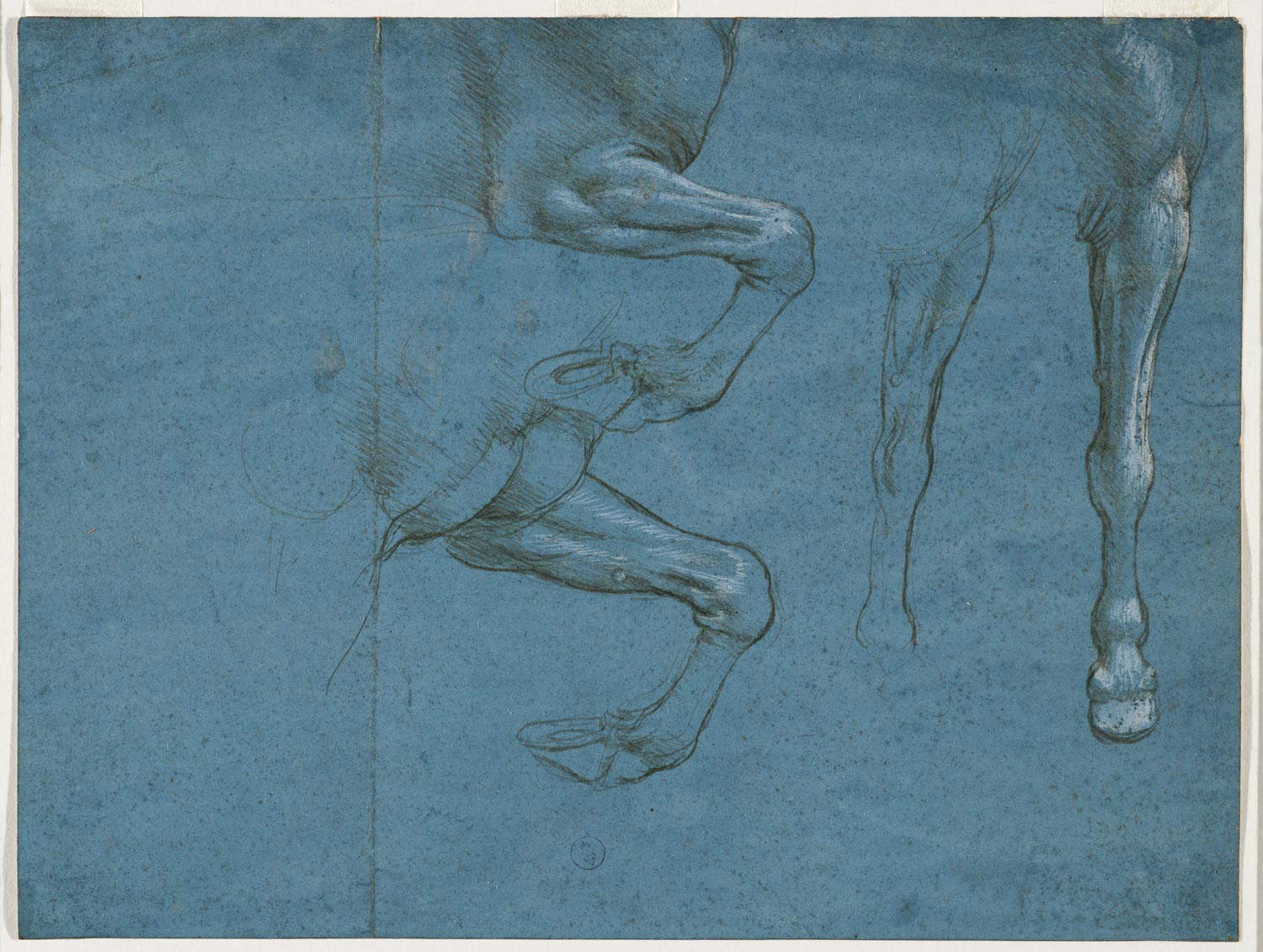

We have no information on how Volpato obtained the sheets. “However, the nucleus appears,” its director, Giuseppina Mussari, explains in the Library’s guide, "as a non-random set, almost an anthology of the Florentine genius that covers almost the entire time span of the artist’s life and traces his main motives and interests. It is a very diverse nucleus, with the extremes placeable from about 1480 to 1515-1517, and also with a vast congeries of subjects, from designs for paintings and sculptures to studies of animals, from investigations of the human face to anatomical investigations. After theSelf-Portrait, the best-known drawing is probably the Maiden’s Face, an experiment conducted by Leonardo on the subject of the shoulder portrait, reflecting what the artist learned at the workshop of Verrocchio, his master, so graceful that it was called the most beautiful drawing in the world in 1952 by Bernard Berenson. It is one of the earliest works in the collection, dating from around 1483-1485, and has been read as a preparatory study for the Virgin of the Rocks, although there have been those who, though having little follow-through, have believed it to be a depiction of Cecilia Galleani, mistress of the Duke of Milan, Ludovico il Moro. Also from the same period, though earlier, is the Study of the musculature of the front legs of a horse, considered to be Leonardo’s earliest drawing in the core of the Royal Library: it is possibly a study for the never-made equestrian monument to Francesco Sforza. As many as three drawings with studies of horses by Leonardo da Vinci are preserved in the Royal Library of Turin.

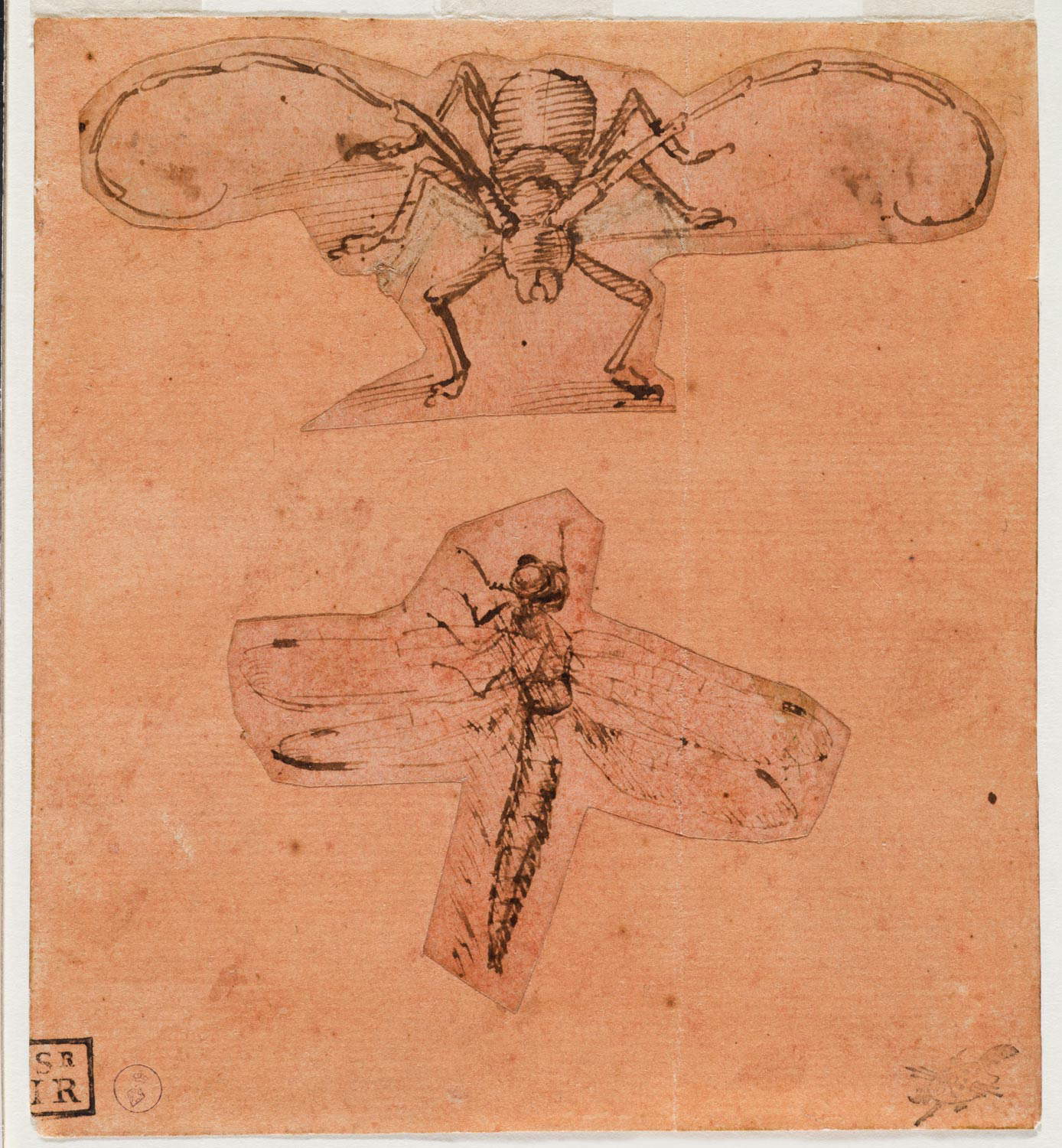

Always an eye on the animal world is what emerges from the peculiar drawing with two studies of insects, traced on two separate fragments of paper and then glued on a single sheet: the one at the top depicts a cerambyx, a beetle similar in appearance to a beetle but distinguished by its very long antennae, while the one in the lower one we see a dragonfly or a formicaleon, an insect the latter similar to the dragonfly but with a stockier body and longer antennae. The two insects are depicted in their structure and in the absence of movement, a circumstance that, writes art historian Antonietta De Felice (who calls this drawing a work “of delightful workmanship”), “draws attention to the sole form of the insects in which the veins of the wings, the membrane of the body structure, and the precise line of the legs are visible. In the work, in addition to grasping the incredible correspondence to reality, the great wealth of detail in the depiction of the two insects is clearly evident.” It is likely that the studies of insects were related to studies of flight: Leonardo intended to analyze the structure of insects to understand how it enabled them to fly.

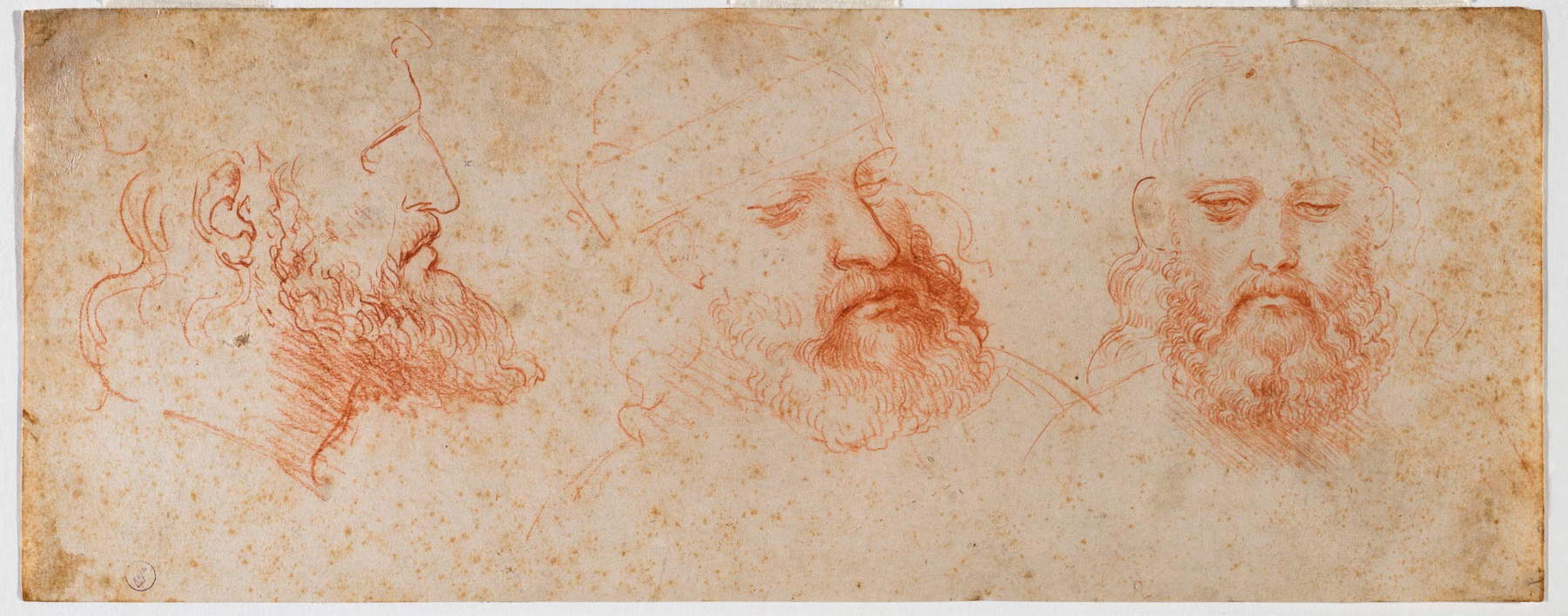

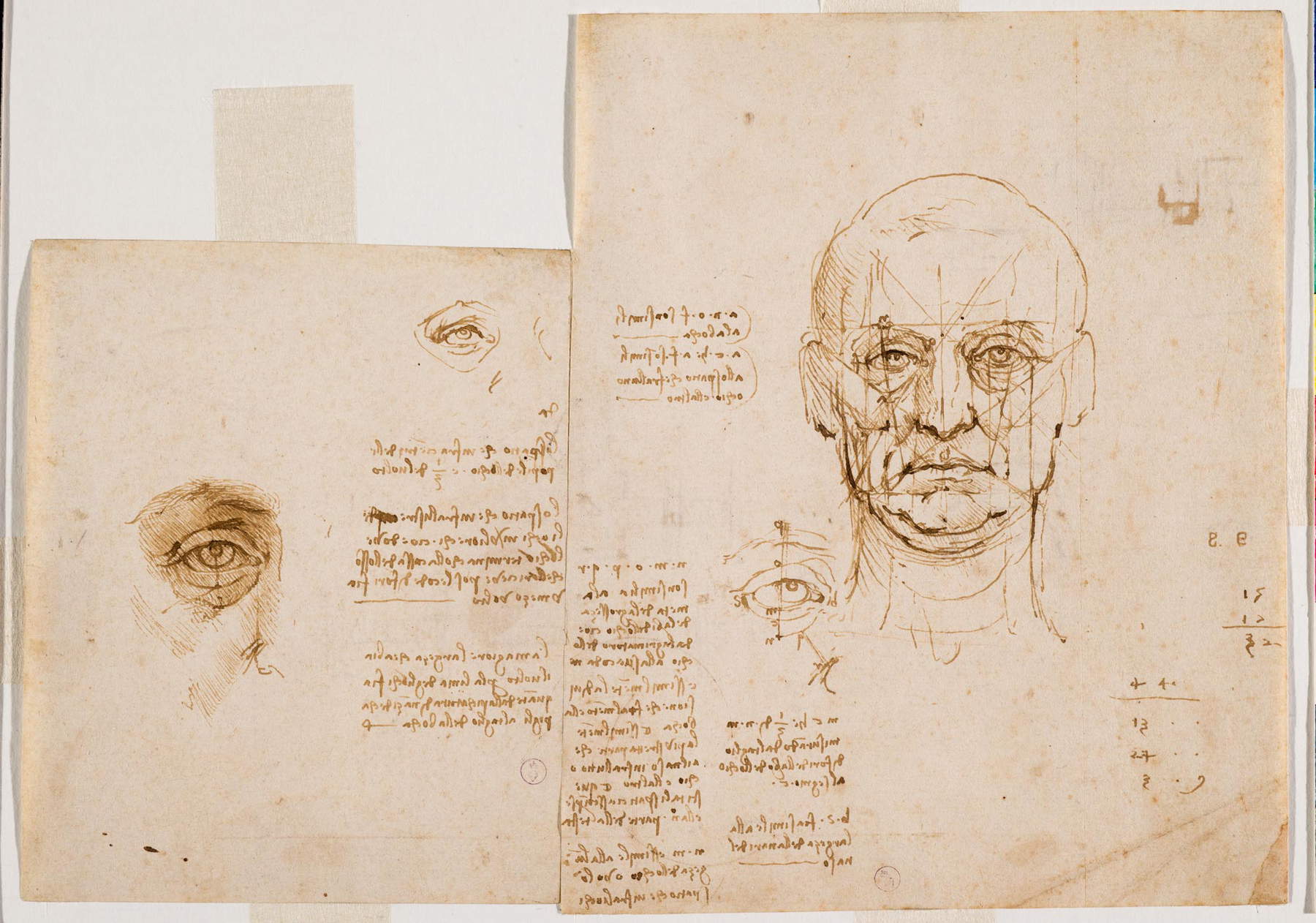

In the Turin corpus there is, of course, no shortage of studies of the human figure. We can start with a sheet with three heads, although they all refer to the same person: it is a face with a medium-length beard and shoulder-length hair, which is portrayed frontally, three-quarter view, and in profile. The subject has been variously interpreted: the most popular hypothesis is that it is a preparatory drawing for a sculpture, with the study of the three canonical poses that formed the basis for any sculptural design. As for the identification of the personage, it has been proposed (by art historian Wilhelm Reinhold Valentiner in 1930) to read the drawing as a study for a portrait of Cesare Borgia, an idea that has met with wide approval but also with some illustrious critics, such as that of Carlo Pedretti, according to whom it would instead be a man whom Leonardo met only occasionally, and who perhaps attracted him because of his somatic features. Pedretti himself brought together, in 1975, two fragments on a single sheet, depicting an eye and a face respectively, which can be related to the studies of proportion that Leonardo da Vinci was conducting around 1490 and of which theVitruvian Man is also a part. Interestingly, both the eye and the head bear explicitly their proportions, and the eye also has reference points illustrated by Leonardo himself in a note.This sheet thus represents a very interesting example of the scientific method that Leonardo da Vinci employed when observing the phenomena of the world.

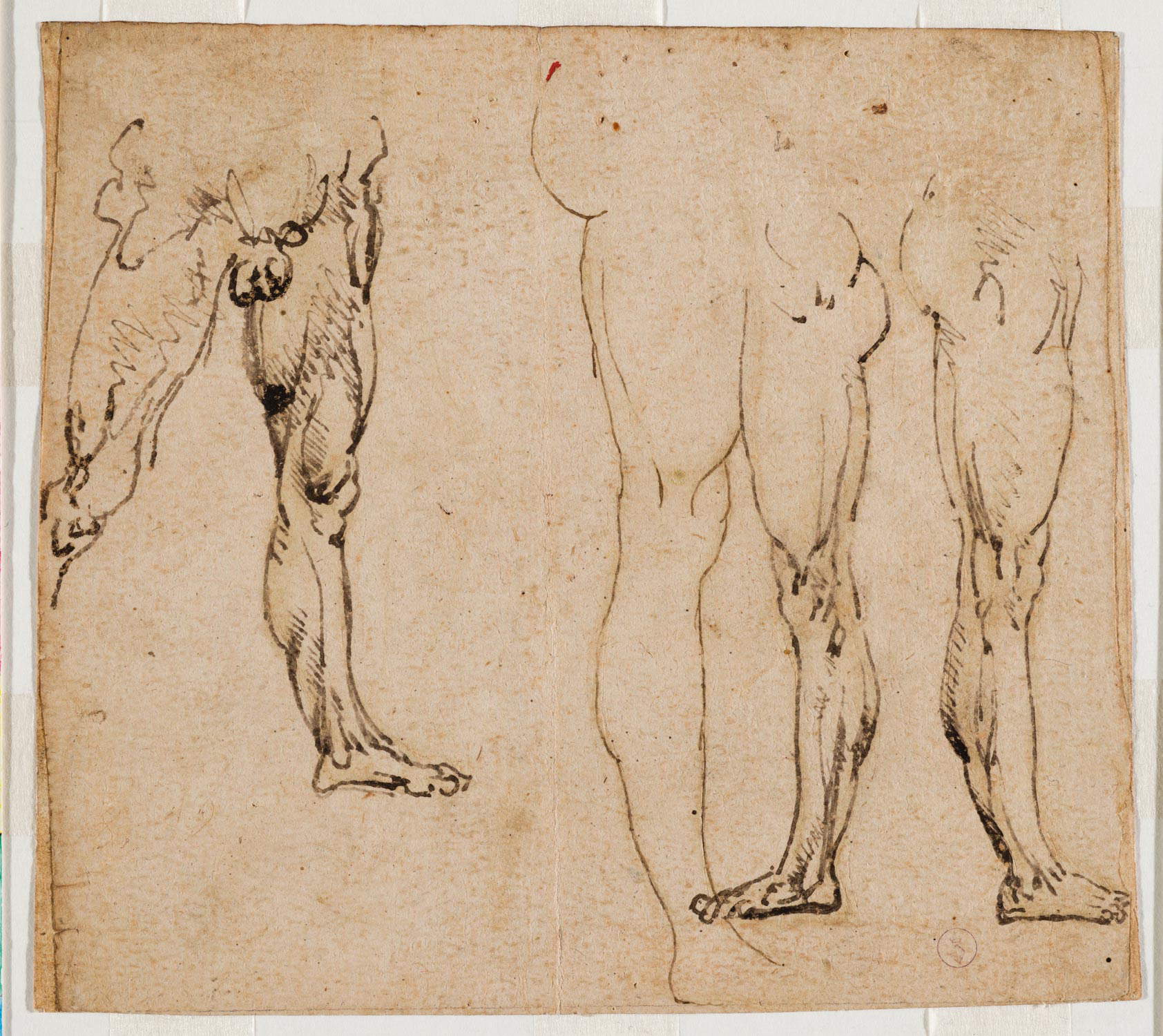

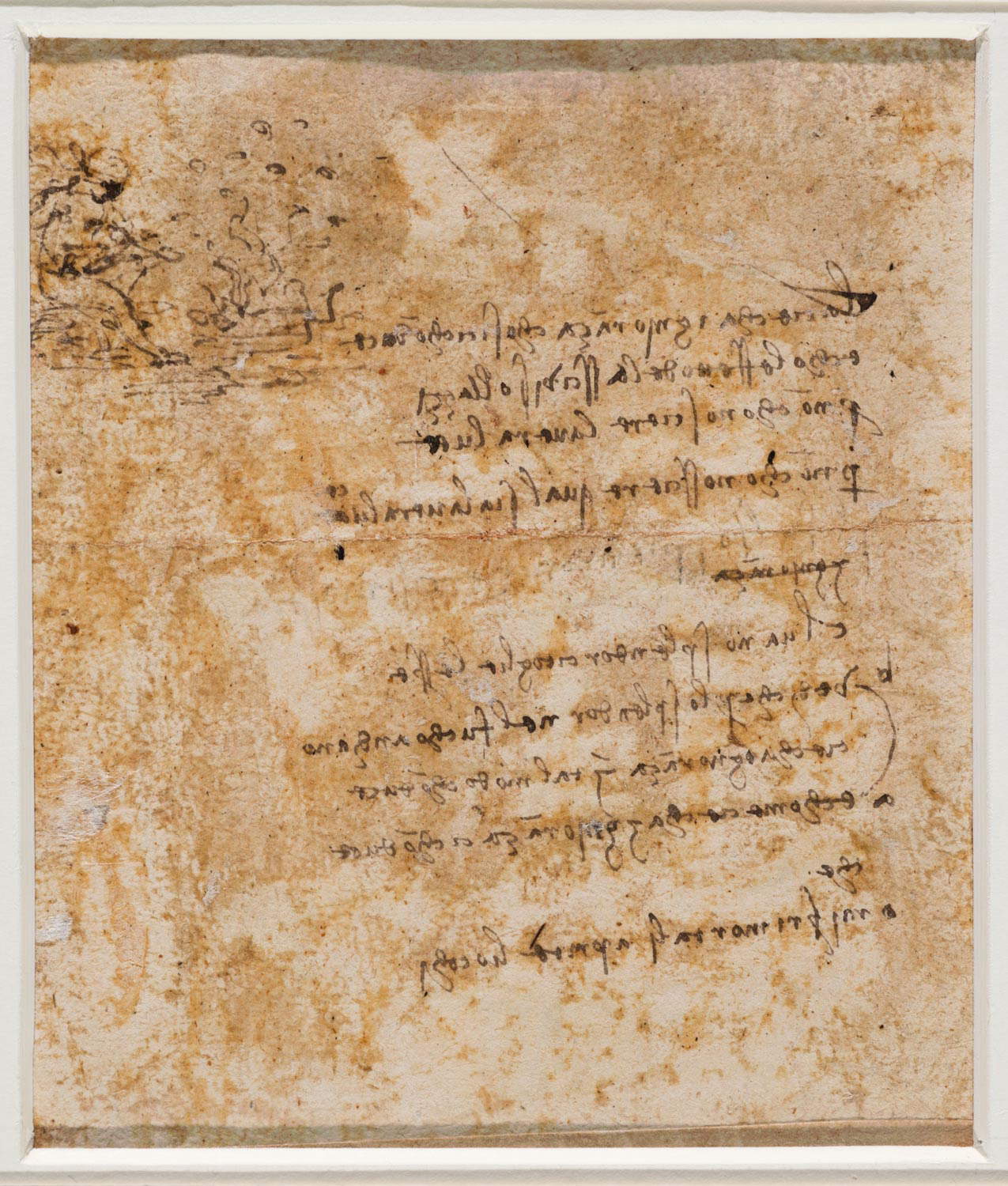

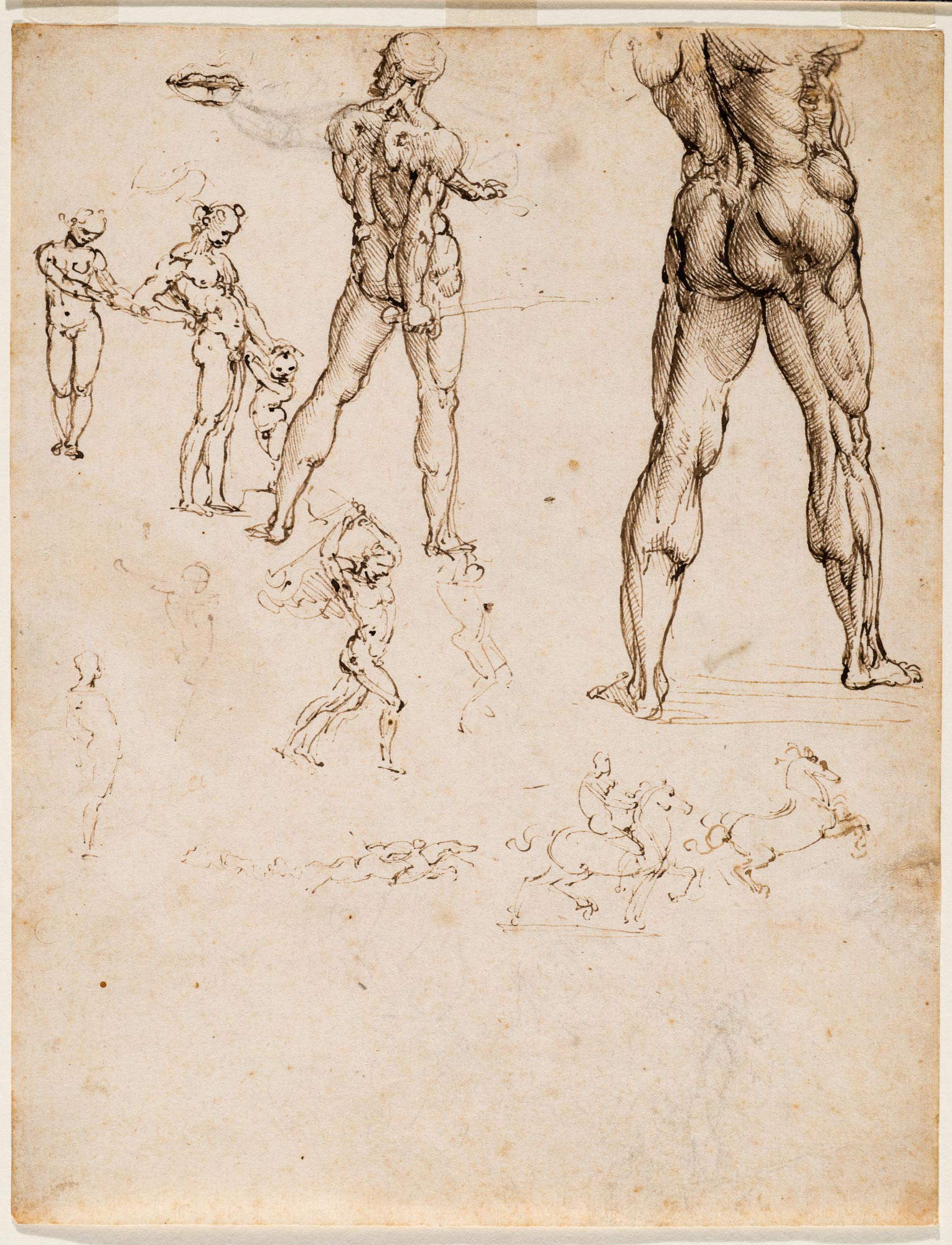

Also belonging to the same vein, that of anatomical studies, is a drawing depicting two virile legs: here, Leonardo da Vinci focuses on the anatomy of the lower part of a male body, carefully studying a pair of legs and their muscle bands. On the verso of the drawing, Leonardo traced an interesting seated female figure, holding in her lap some dry twigs that are thrown to the ground to feed a fire over which some butterflies fly. Next to the drawing, Leonardo wrote some endecasyllables to explain this singular, to be understood as an allegory of the quest for knowledge, which involves the risk of getting lost if lured by false lights: “la ciecha ignjoranza cho si ci choduce / e cho leffetto de lasscivj sollazzj / per no chonosciere la uera luce / per no chonossciere qual sia la uera luce / (Jgnjoranza) / vedj che per lo splendor nel fu[o]cho andjamo / ciecha ignoranza j tal modo choduce / che / o miseri mortalj aprite liochj.” The leg study has been traced back to the preparation of the Battle of Anghiari for the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, to which another preparatory sheet, the one with some nudes and other figure studies, should also be referred: in the foreground a warrior seen from the back, from the shoulder blades down, then a body in torsion, some naked combatants in the lower part of the sheet, and other figures sketchily drawn.

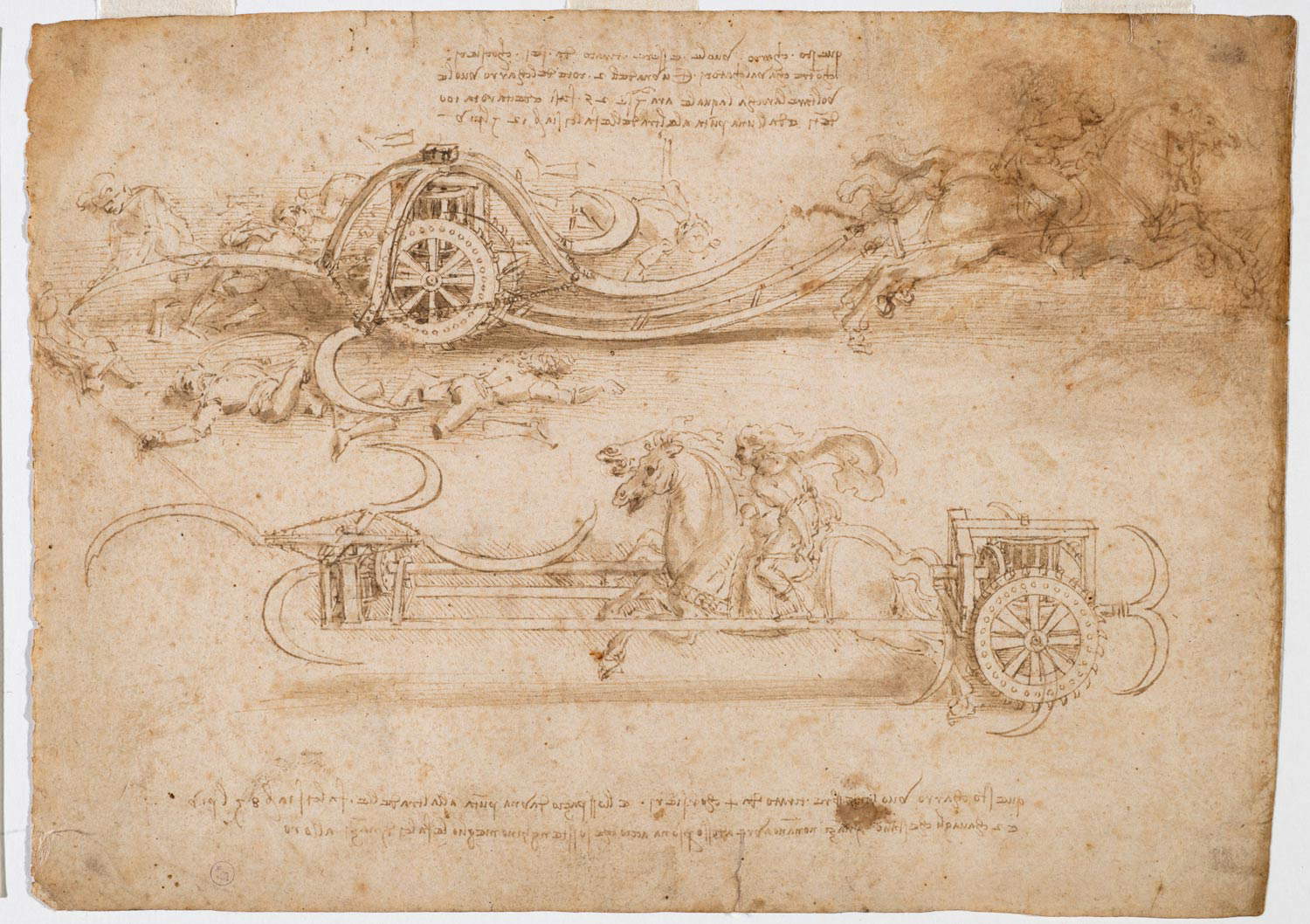

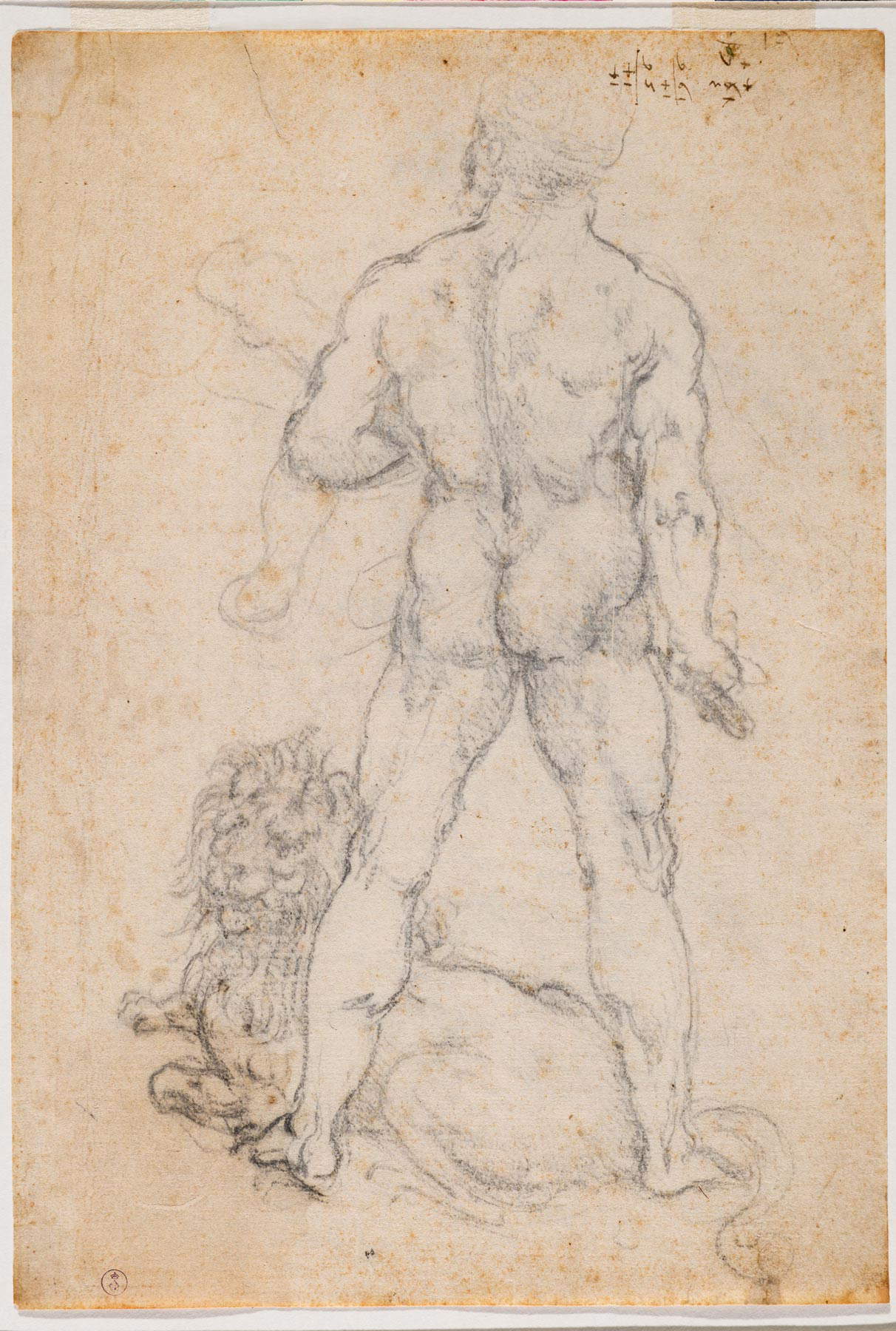

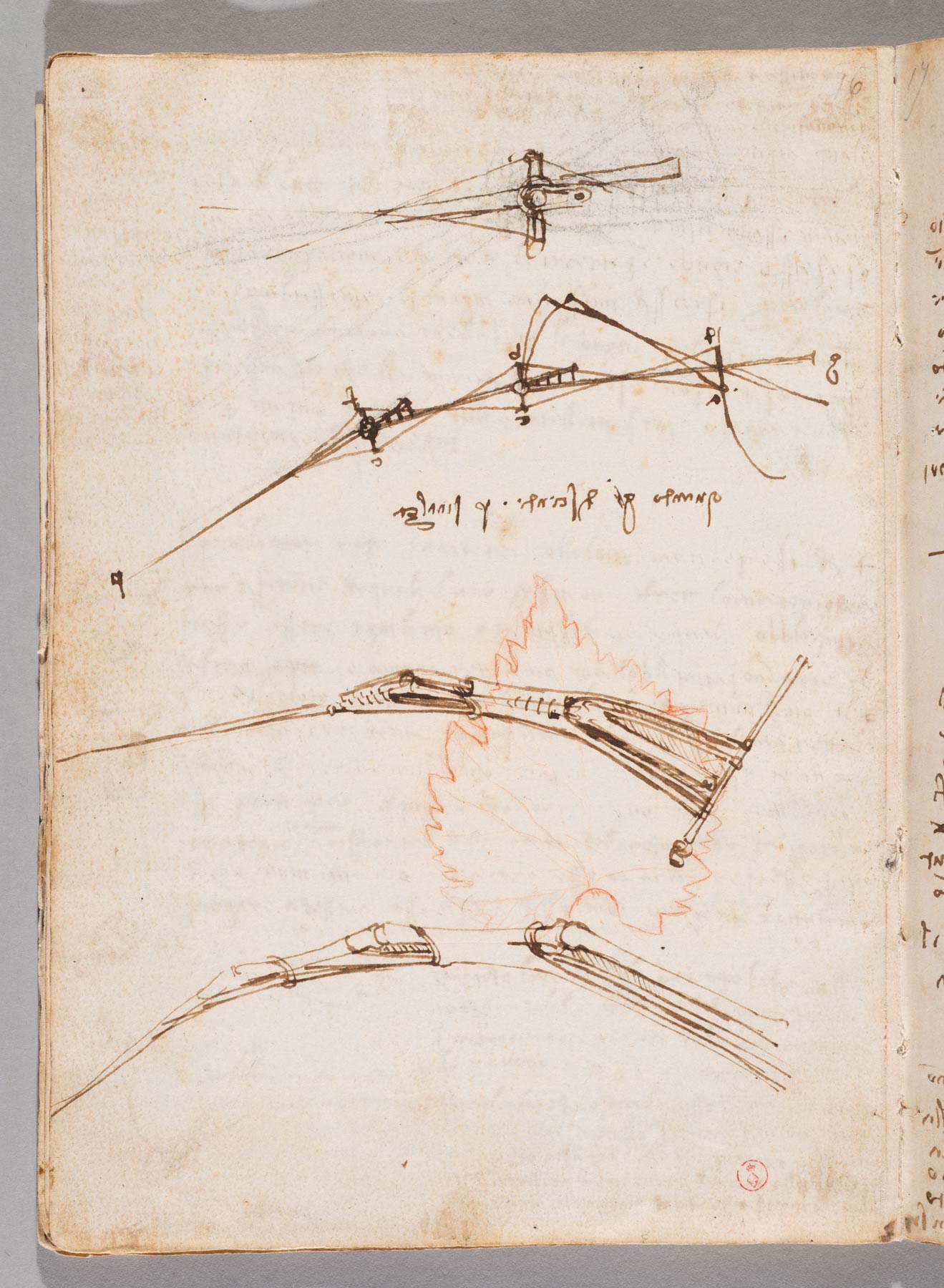

And speaking of battles, a sheet with studies of “falcate chariots” is also preserved in Turin, an example of Leonardo da Vinci’s military engineering skills, despite his opposition to war. The falcati chariots in Leonardo’s intentions were to be two war machines pulled by pairs of horses: on the sides they were to be equipped with blades connected to wheels that were to make these chariots a fearsome weapon, capable of literally mowing down enemies by cutting off their lower limbs in order to make their way across the battlefield. This macabre machine is investigated in its operation (Leonardo shows the interlocking mechanisms, the wheels, the pivots, the scythes) and in the consequences of its action (the drawing, a grim detail, also shows the bodies being cut to pieces). A much quieter drawing is the one with the manly Head in profile crowned with laurel, probably a study for an idealized classical hero, as the laurel wreath on his head would certify, which would date from the period of the Battle of Anghiari, given the similarities with some of the anatomical models of the warriors imagined for the Palazzo Vecchio. The last drawing is another ancient hero: it is a Hercules with the Nemean lion, depicting the mythological demigod seen from behind, holding the club and with the Nemean lion, still alive at his feet (he will be killed by Hercules in the course of the first effort). A drawing that has created some headaches for scholars, because in ancient times it was traced with a metal point in order to transfer the figure to another support, and this operation compromised the original mark, which is essential to allow a safe attribution: however, to assign the sheet to Leonardo was Carlo Pedretti, on the basis of comparisons with other drawings. TheHercules was recognized by Pedretti as a preparatory drawing with a view to the creation of a statue of Hercules similar to Michelangelo’s David: the project would later come to fruition with Baccio Bandinelli’sHercules and Cacus, finished in 1533.

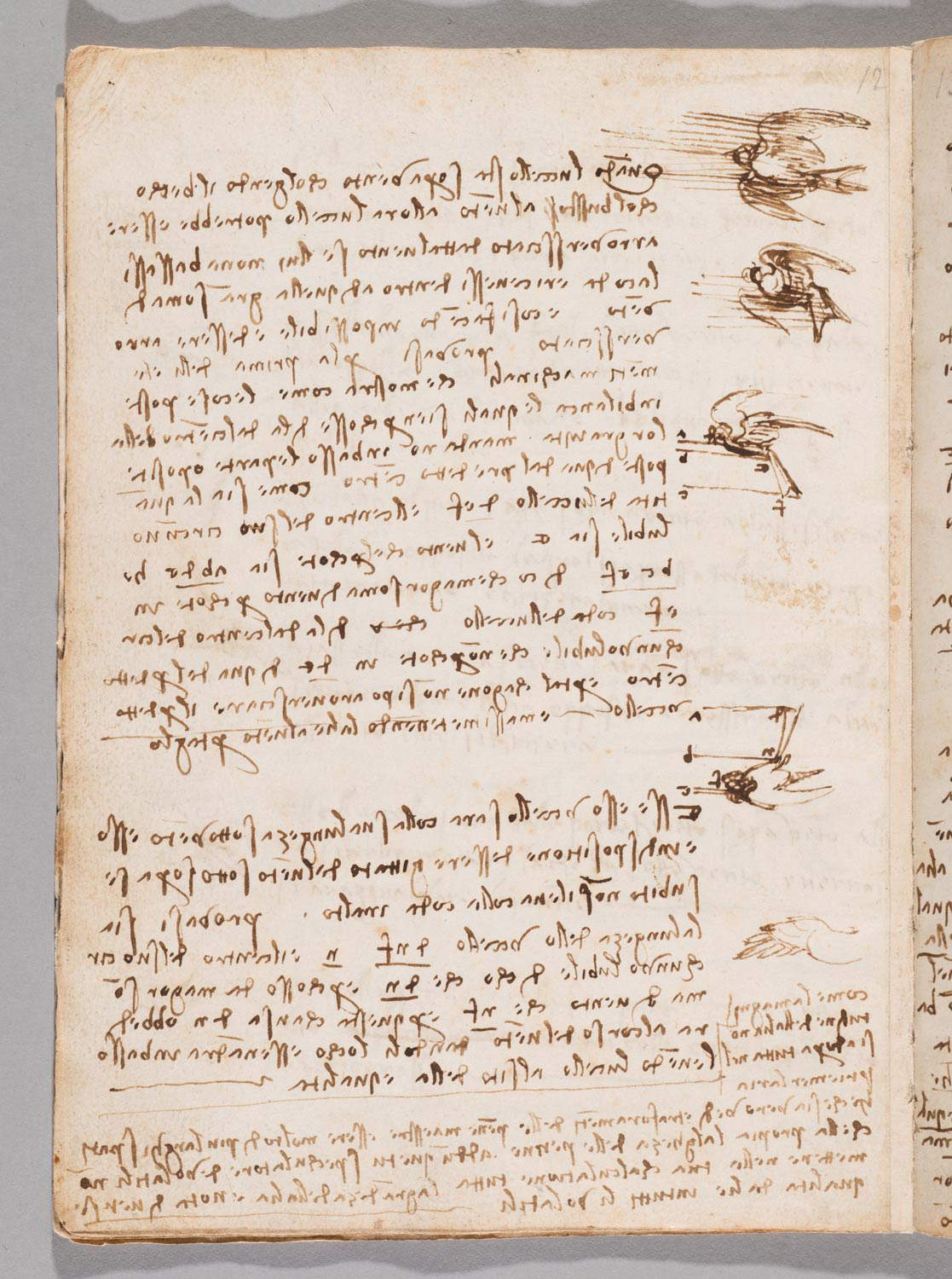

Finally, as anticipated, the Royal Library of Turin also preserves the Codex on the Flight of Birds, one of the most original results of Leonardo da Vinci’s innovative studies on flight, based on method, observation of nature and experimentation. Studies on the flight of birds date back to the early 16th century, the time of his return to Florence from Milan: the Turin manuscript itself, which is not part of the nucleus sold to the king by Giovanni Volpato (it was in fact added to the Library’s Leonardo collection in 1893, donated by the Russian collector and scholar Fyodor Vasil’evič Sabašnikov to Umberto I), collects most of Leonardo’s observations on the way some birds manage to soar through the air. Leonardo studies their trajectories, their body structure, the way they take advantage of the wind, their adaptation to different air conditions: the goal is to design machines that would enable humans to fly as well. He would not succeed, too far ahead of his time, but his studies represent one of the foundations of the science of flight.

Today, Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings in the Royal Library of Turin are kept in two special rooms, created in 1998 and 2014 thanks to the intervention of the Council for the Enhancement of the Artistic and Cultural Heritage of Turin, which allow these precious sheets to be kept in measured and controlled conditions of temperature, humidity and lighting. A location that has also, moreover, facilitated the display ofthe drawings, which are periodically exhibited to the public, albeit for short periods: although the new rooms have improved the conservation of the drawings, these treasures of the Royal Library of Turin remain delicate sheets that cannot see the light for too long, but must be given long periods of rest in order to be preserved for the future.

The foundation of the Royal Library of Turin is owed to Charles Albert of Savoy, who in 1831, as soon as he ascended the throne, added to his plans the construction of a court library, which in his intentions was to, on the one hand, increase the prestige of the dynasty, and on the other hand to make available up-to-date tools for the education of its ruling class. Charles Albert entrusted a group of collaborators, selected from among the best intellectuals working at court, with the task of acquiring the most valuable items on the European market. Among manuscripts, printed books, engravings, ancient maps, and etchings, the results of the campaign came very soon, so much so that as early as 1837 the collection needed its own space. The task was entrusted to architect Pelagio Palagi, who in the east wing of the Royal Palace created the library vessel topped by the decorated vault. The new Library was inaugurated in 1842, but the real turning point for the collection came three years earlier, in 1839, when Charles Albert purchased from the merchant Giovanni Volpato a nucleus of more than 1,500 folios by Italian and foreign masters, including Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Dürer, Tiepolo, Piazzetta, and Leonardo’s 13 autographs.

The Royal Library of Turin thus became, from the very beginning, a destination for scholars and enthusiasts, all of whom were eager to take a closer look at the trait of Leonardo’s genius. Leonardo’s autographs, including the celebrated Self-Portrait, are not the only rare pieces in the collection, however: the latter also include maps, and in particular the great nautical geocarta of Giovanni Vespucci, Amerigo’s grandson. Today, as a whole, the Library holds about 200,000 volumes, 4,500 manuscripts, 3,055 drawings, 187 incunabula, 5,019 cinquecentine, 1,500 parchments, 1,112 periodicals, 400 photographic albums, maps, engravings and prints. The collections continue to be augmented by purchases on the antiquarian market, although still today the majority of the works in the Royal Library belong to the historical collections of the House of Savoy.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.