The crisis triggered by the coronavirus has undeniably disrupted every area of human making, often forcing a rethinking of methods and approaches. Cultural venues have been no exception; and if in the lockdown period the need was to be able to communicate and disseminate cultural heritage by experimenting with new methods of mediation, especially through digitization, now the need is instead to ensure their cultural service while protecting the health of visitors and workers. The crisis has brought a proliferation of reflections around the uncertain future of museums, as they are depleted by large tourist flows and plagued instead by new economic efforts to be addressed, in terms of protection, maintenance and adaptation to new health regulations. Although returning to an apparent situation of normalcy seems to be the main goal, there are not a few who have pointed out that this will not be enough, as cultural institutions face new challenges that cannot be prolonged. Back in March in an interview in Finestre Sull’Arte, Uffizi Director Eike Schmidt posed the rhetorical question of whether it really was enough to return to the previous situation.

Museums had long since been invited to face the new challenges that the 21st millennium has brought with it: digitization, countering mass tourism in favor of a sustainable tourism no longer in favor of a few art cities, deseasonalization, new cultural policies that involve local communities, an offer that knows how to make popularization and research coexist with moments of entertainment; to name but a few. While there obviously cannot be a one-size-fits-all solution to respond to these tasks, there is still a need to explore new alternatives to the traditional concepts of museum and monument: ecomuseums are an example.

An extraordinary contribution on the future of museums was postulated a few years ago by the Turkish writer and Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk, who in July 2016 opened the XXIV Conference of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) with a speech that took the form of a decalogue of good intentions to be adopted by museums: “[...] the future of museums is within our own home. The situation is quite simple: we have been used to having epics but what we need are novels. In museums we have been used to representation, but what we need is expression. We have been used to having monuments, but what we need are houses. In museums we used to have History, but what we need is stories. We used to have nations in museums, but what we need is people. We had groups and factions in museums, but what we need are individuals.”

In his decalogue, the Turkish writer insists on the term home, as it stands as an archetype across virtually all cultures, an intimate and familiar place.

On closer inspection, there is a museum typology that really takes on these values and often meets the demands of innovation required of museums, but at the moment it does not seem to enjoy much interest, particularly as far as studies are concerned. I am referring to house museums related to the lives of illustrious personalities, that is, those houses that take on a symbolic value for a given community, after they have been inhabited (even for a short time) by a person recognized as deserving and his or her memory worthy of being handed down to future generations. Often, their specificity is not recognized, and the imagery associated with the term house museum is almost totally catalyzed on those extraordinary houses that are the result of the collecting efforts of a few wealthy owners (examples are the Poldi Pezzoli Museum, the Stibbert Museum and the Bagatti Valsecchi Museum).

Yet, in the face of this terminological indeterminacy, house museums linked to illustrious personalities are experiencing, in Italy and abroad, a fortunate season: in fact, there are hundreds of house museums pertaining to this typology that have been opened over the past two decades; moreover, they are increasingly at the center of the cultural programming of territories, especially on the occasion of important celebrations, becoming privileged theaters of commemorations of great personalities, such as the house of Raphael in Urbino this year and the house of Leonardo in Vinci in 2019.

To date, it is difficult to have overall data on house museums related to this typology, however, for some time now some entities have been engaged in the promotion of circuits that collect the houses of illustrious men, with the intention of enhancing their knowledge, as well as creating tourist and cultural itineraries, and allow us to have an idea of the extent of the phenomenon.

DEMHIST(demeures historiques) is an ICOM committee created in 1997 with the aim of attempting a systematic reorganization of the multifaceted world of house museums. Over time it has proposed new classifications by identifying various sub-types, including precisely “houses of distinguished personalities,” “houses of collectors,” “houses of the clergy,” “houses dedicated to historical events,” and so on. DEMHIST also championed the compilation of a directory of more than 150 house museums worldwide, of which 26 belong to the “house of illustrious personalities” typology (while the Museo Italia portal enumerates more than 102 houses pertaining to this typology).

House museums are often collected in circumscribed networks on the basis of the professions, virtues, and vocations for which their inhabitant became illustrious. Thus, studies, publications and research, directories and itineraries of “writers’ houses,” “saints’ houses,” “politicians’ houses,” and others have been created.

Writers’ houses seem to be in greater numbers both at the European level and in Italy. In 2007 there were over 203 maison d’écrivains in France and over 60 in Italy. To date, www.casediscrittori.it has more than 150 musealized places between houses and literary parks dedicated to the memory of famous writers.

In Italy, particularly active are “Le Case Museo dei poeti e degli scrittori di Romagna” and the "Case della memoria" Association. The latter was officially formed in Prato in 2005, promoted by the Tuscany Region and Casa Boccaccio, and today has 76 houses scattered in 12 regions, although not all of them are used as museums. In 2015, the association signed in Florence the European Cooperation Protocol between the National Association of Houses of Memory, and numerous house museums, officially creating the European Coordination of Houses of Memory.

|

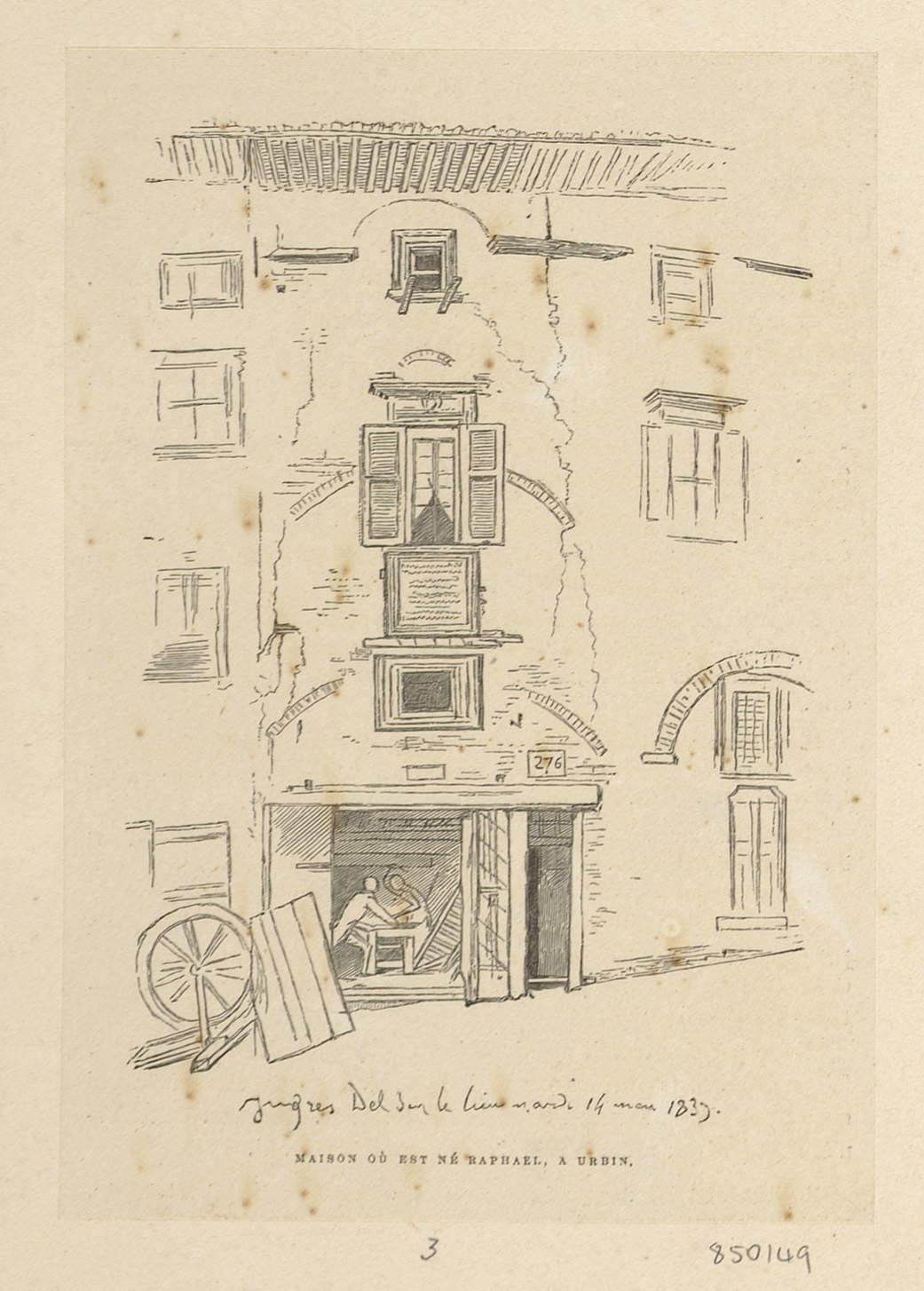

| Raphael’s birthplace in Urbino depicted by painter Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres is published in the newspaper Gazette des Beaux Arts (1837) |

|

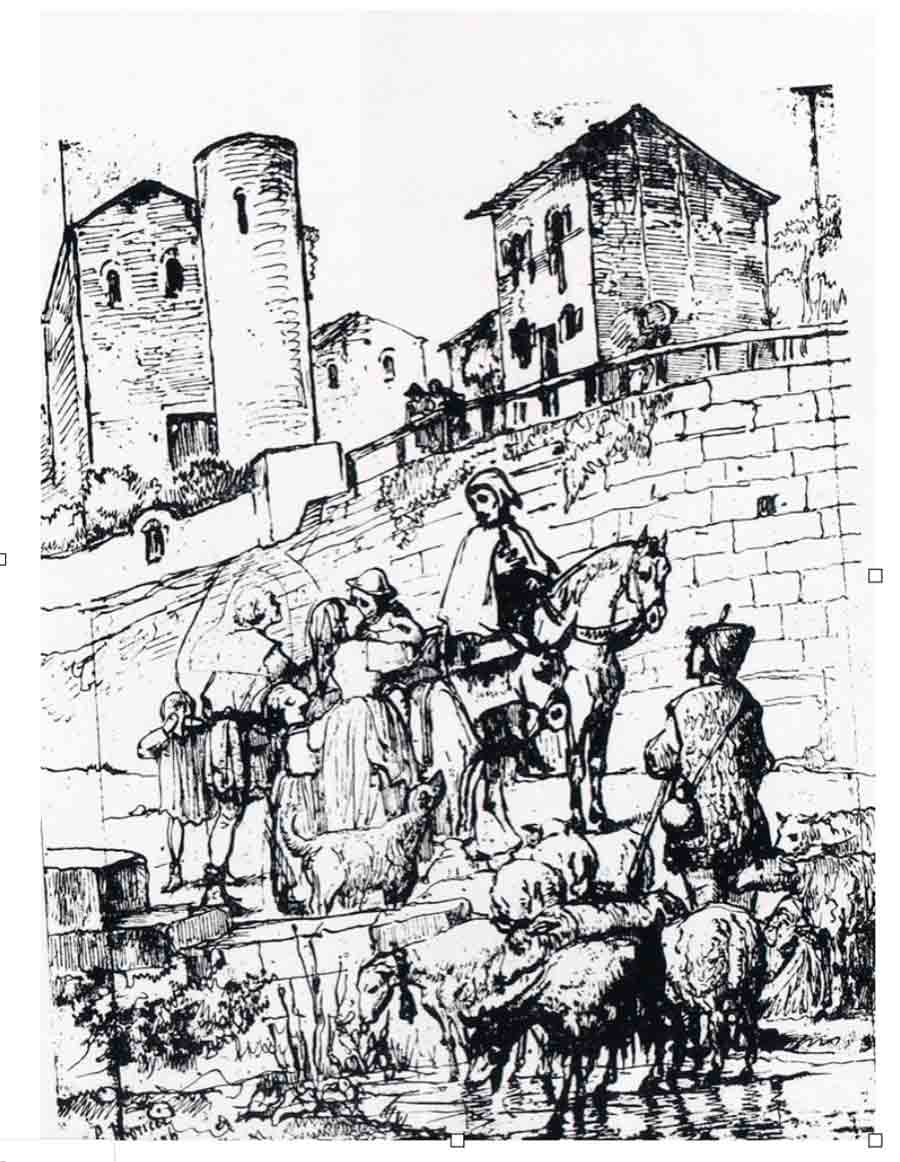

| In Giuseppe Moricci’s drawing Giotto leaves his family to travel to Florence accompanied by his master Cimabue (1876, private collection) the scene is set with the artist’s birthplace in the background. |

But how do house museums of illustrious personalities come into being and when do they come into being? The “houses of illustrious personalities” have been a destination of pilgrimage and interest since time immemorial, just think of the places associated with the life of Christ in the Holy Land or the houses of saints in Italy. In some ways a kind of devotion, though purely secular, also involves the houses of personalities such as men of letters, playwrights, poets, artists, scientists, and so on. Indeed, the houses become functional for the commemoration and celebration of the personalities to whom the visitor pays homage with his presence, seeking to come into contact with them through his living space.

They are dwellings, which sometimes coincide with valuable architectural emergencies, but most of the time they are anonymous buildings that do not stand out for their architecture, nor for decorative excellence. Their preservation is thus given solely by the historical and symbolic value they carry. These buildings stop being ordinary spaces to become places of high symbolic value only through “the operation of narrative,” as scholar Antonella Tarpino defines it. The houses, preserved by the community, are marked with plaques, tombstones, epigraphs and busts, and later can be reorganized into museums, cenotaphs or public places.

The house does not necessarily have to have belonged to the personage to become his or her monument: it may be dwellings where he or she was merely a guest, such as Goethe’s house in Rome, but which the community decides to commemorate, thus tying the illustrious person to the territory. Other times, it is instead the illustrious person’s family that takes charge of the musealization process, as happened with Antonio Canova’s birth house in Possagno, which was bequeathed, like the rest of the sculptor’s possessions, to his half-brother Giovanni Battista Sartori, and reorganized by transferring there furniture, sculptures and plaster casts from Canova’s Roman studio to popularize and commemorate the great Venetian sculptor, also building a gipsoteca next to it.

If the model from which the houses of illustrious personalities are derived has been translated from the places associated with religious personalities, the secular cult of personality on the places inhabited by him is a very old phenomenon, however.

One of the earliest recorded instances is related to the memory of Petrarch, who in 1350, on his return from Rome, decided to make a brief stop in his hometown of Arezzo. Welcomed with all honors, on his visit he was led in front of his birth house, which had already been placed under protection by the municipal government, which forbade changes to it.

The house inhabited by the poet in Arquà was probably the first case of the musealization of a home associated with a secular personality. The building, in 1564, was in fact purchased by a nobleman from Padua who enriched it with frescoes and paintings dedicated to the works of the man of letters. Inside the house it was possible to visit the poet’s study in which objects that belonged to Petrarch, including the curious mummy of the poet’s cat, were found and are still preserved today

Later, the practice of visiting and remembering houses that belonged to famous people became consolidated, especially with the phenomenon of the Grand Tour.

|

| The color workshop in Giotto’s house in Vespignano (Florence) dedicated to educational activities |

|

| The house where Petrarch lived the last years of his life in Arquà (Padua) |

|

| The house where Leonardo da Vinci was born in Anchiano (Vinci) |

|

| The house where Antonio Canova was born is part of the Antonio Canova Museum and Gypsotheca in Possagno (Treviso) |

|

| The bedroom with the cradle that belonged to the poet in the Casa Pascoli Museum in San Mauro Pascoli (Forli-Cesena) |

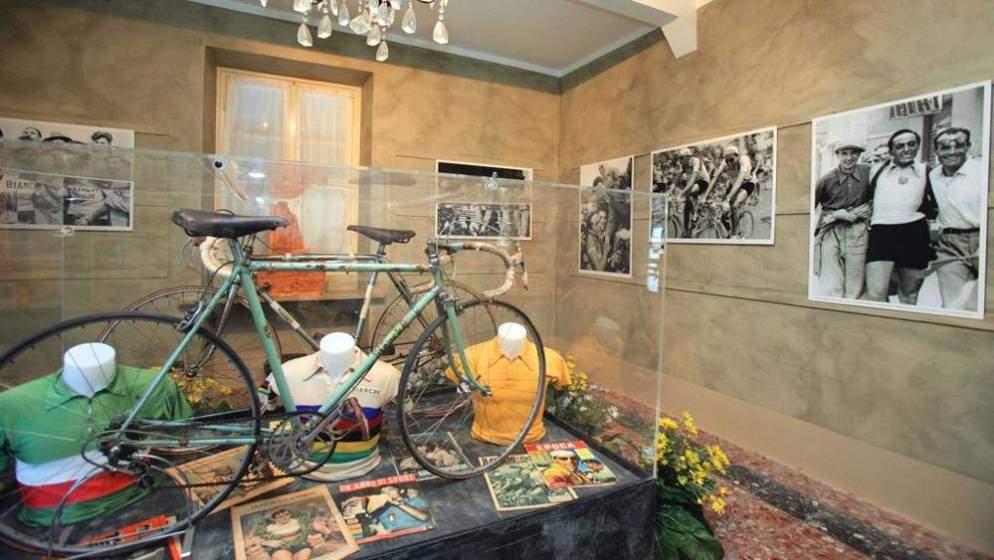

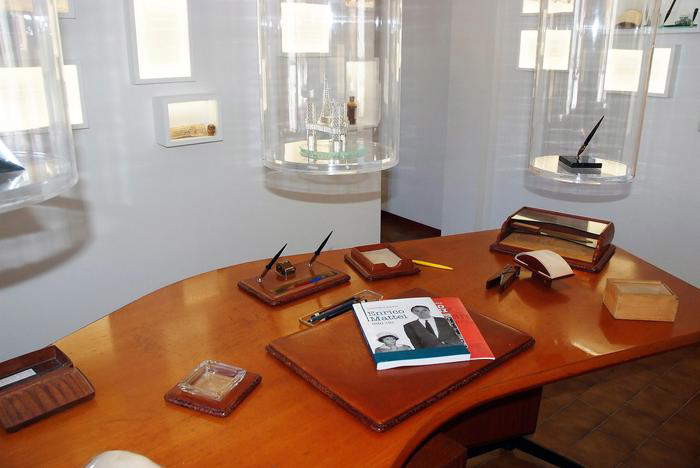

This practice became increasingly common in the last decades of the 18th century: in the season of Romanticism and with nationalistic echoes, houses linked to illustrious personalities took on a pedagogical and propagandistic function. The house, as a place where the genius loci is manifested, is promoted by institutions that offer the life of the illustrious man as a moral and identity example of a nation. Examples are the house of Raphael in Urbino and the house of Dante in Florence. In this cultural policy based on strong involvement, the documentary value of authenticity took a back seat, so much so that as in the case of the Supreme Poet the house was identified through ambiguous documentary sources. Fascism, too, continued this cultural policy to impose its “symbolic arsenal,” adding new house museums to the national itinerary, such as the House of Benito Mussolini in Predappio, which was musealized while the Duce was still alive, with reconstructions of the family environments and equipped with a catalog and signature book. During this period many houses of patriots and fathers of the fatherland were named national monuments. From the postwar period to the present, there has then been a proliferation against all odds of this museological typology. Initially, the new heroes to be muselized were partisans and opponents of the regime, but these were joined over the decades by new idols: sportsmen, entrepreneurs, singers, and many others. In a hamlet of Florence, Ponte a Ema, it is possible to visit the “Gino Bartali” Museum of Cycling, and the same has been done for the other legendary cyclist Fausto Coppi at the house where he was born in Castellania in Piedmont; while in Acqualagna in the Marche region it is possible to visit the house-museum of the founder and president of Eni, Enrico Mattei; in Modena, on the other hand, the MEF (Museo Casa Enzo Ferrari) dedicated to the life and work of Enzo Ferrari, the founder of the car manufacturer, has been opened.

In short, the house museums of illustrious personalities have had a long and multifaceted journey, carrying very different values over time, but also an idea of a museum that still remains unchanged today: the awareness of the high symbolic value of places, once the scene of the lives of well-deserving personalities, and therefore particularly suited to involve the visitor emotionally through the sensation of contact with the illustrious and with his or her intimacy. In this emotionally based involvement, the documentary and historical value sometimes slips into the background, and the houses may be set up with criteria more aimed at satisfying the visitor’s imagination than with reliable historical criteria, as happened with the reconstruction of Juliet’s House in Verona, orchestrated by Antonio Avena, in which some architectural details, such as the balcony, were arbitrarily inserted.

|

| A detail of the tenor Enrico Caruso’s museum at Villa Caruso Bellosguardo in Lastra a Signa, Florence. |

|

| Fausto Coppi’s birthplace in Castellania (Alessandria, Italy) |

|

| Enrico Mattei’s desk preserved in the house museum (Pesaro-Urbino) |

|

| Juliet’s house in Verona |

The panorama of house museums, however, offers interventions conducted in very different manners, from the more or less deliberate reconstruction of living places, to the space left almost completely empty with the intention of enhancing the few remaining original elements, as is the case, for example, with the house where the painter Pontormo was born, near Empoli.

These buildings often arise in small cities, towns and villages not affected by large tourist flows, in places moreover often devoid of other cultural institutions, so in addition to the main objective aimed at the dissemination and knowledge of the memory of the illustrious, coexist other purposes, related to the enhancement of the territory and becoming a place of aggregation and cultural center for the local community.

For example, the house in which the painter Cima was born in Conegliano also houses an archaeological and numismatic exhibition, while Antonio Gramsci ’s house in Sardinia organizes debates and meetings of various kinds, including in-depth discussions on the condition of Sardinian workers.

These are museums whose strength lies in the innate narrative and symbolic qualities with which they are endowed, since they allow for experiences as diverse as the museographic devices put in place are different. They often make use of new virtual and multimedia technologies, as in Giuseppe Verdi ’s house in Busseto, where the shadow of the child Verdi accompanies visitors through the environments of his childhood. They thus become bearers of different values, which in the most successful cases manage to bring together, the symbolic, the playful and the documentary or educational value.

For these reasons, the house museums of distinguished personalities are a very modern museum alternative; in fact, they meet the definition of a museum provided by ICOM in 2007: "A museum is a permanent, nonprofit institution at the service of society, and its development, open to the public, which researches the tangible and intangible evidence of man and his environment, acquires, preserves, and communicates it, and specifically exhibits it for purposes of study, education, and enjoyment."

House museums succeed in conveying experiences on tangible and intangible evidence, the latter often marginalized in other kinds of museums. In addition to this, with their peculiar reconstructed or evoked environments, they fit into a particularly fortunate period for historical displays, which in the 21st century are experiencing a kind of new youth, with the overcoming of the hierarchy of knowledge and offering a multidisciplinary approach with the aim of offering contemporary audiences a scientific, but more empathetic reconstruction of History. The homes of celebrities then offer innovative and unprecedented possibilities to enhance the territory by pandering to the growing demands of a new cultural, experiential and, above all, sustainable tourism, which brings economic, cultural and social spin-offs to the whole territory, going to constitute part of that "diffuse museum" of which Italy rises to paradigm in Europe and the World. Such museums participate in a democratic redistribution of tourist flows, constituting themselves as a tourist attraction for the small towns and villages in which they are located; they prove to be particularly ductile tools for the promotion of the territory, offering the small territorial reality the opportunity to avail itself of the appeal given by the fame of the illustrious.

These museums carrying a load of everyday stories and centuries-old memories would seem to respond perfectly to the demands raised by the Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk in his “Decalogue of a museum that tells everyday stories,” and they stand as one of the possible alternatives from which to start for a new sustainable cultural tourism.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.