In the vast and articulated panorama oftwentieth-century Italian art, Giorgio Morandi (Bologna, 1890 - 1964) and Lucio Fontana (Rosario, 1899 - Comabbio, 1968) represent two seemingly opposite poles, united, however, by a common tension toward the infinite. Their diversity of language, temperament and poetics translates into a quest that, while following divergent paths, confronts the limits of representation, matter and space. Exhibiting Morandi alongside Fontana, as is the case in the exhibition at CAMeC in La Spezia that sought to bring them closer together(Morandi and Fontana. Invisible and Infinite, curated by Maria Cristina Bandera and Sergio Risaliti, from April 12 to September 14, 2025), means proposing a dialogue between two visions that revolutionized the way of understanding matter and space, two artists who, although they never met directly on a personal or stylistic level, were able to redefine the coordinates of Italian art, and not only.

Giorgio Morandi traversed the history of Italian art with a trajectory that had no relents or deviations, in a constant work in progress that testifies to his incessant research. His dedication to still life (such as the famous bottles) and landscape, genres that are only apparently obsolete, reveals itself as a continuous actualization and rethinking of the fundamentals of painting, in the light of a tradition ranging from Giotto to Cézanne, passing through Piero della Francesca. Morandi does not simply repeat the same objects obsessively; he denotes an entirely new conception of space. His attention to two-dimensionality, the reduction of depth, and the arrangement of objects on an almost theatrical plane recall both the monumentality of Giotto and the formal synthesis of Piero della Francesca. Roberto Longhi had already pointed out how Morandi knew how to “give even the believed intervals between forms a positive value in fullness,” making the space between objects an active and vibrant element of the composition.

Morandi’s path is marked by a constant reflection on the sources of Western painting: direct knowledge of Giotto’s frescoes, meditation on the works of Piero della Francesca, the lesson of Cézanne, whom Morandi himself acknowledges as his “favorite artist when I started painting.” However, these are not mere formal comparisons, but a profound assimilation of spatial and luministic solutions that are reworked in a personal key. Morandi, as he grasps space in a new way, goes beyond traditional perspective conventions and makes light and color tools to create a still time, a constate present.

In his still lifes, the composition is calibrated with an almost musical care. Objects are arranged according to harmonious rhythms, color tones are reduced to soft, muted color ranges, and light-an inner, mental light-shapes space delicately, dissolving contours, blurring matter until it becomes still, suspended, meditative. The result is a silent, absorbed universe, where time seems to stand still and the gaze is invited to linger, to penetrate the surface to grasp a deeper, invisible, almost metaphysical essence. In the views of Grizzana, in the much-loved landscapes, the same principle applies to rural spaces: sun-baked hills, cracked walls, houses dissolving in the light, country roads leading into the void. Here, too, Morandi constructs a motionless time, an eternal present. There is no narrative, no event, only contemplation. Each painting becomes a casket in which the visible becomes a gateway to what cannot be seen, but only sensed.

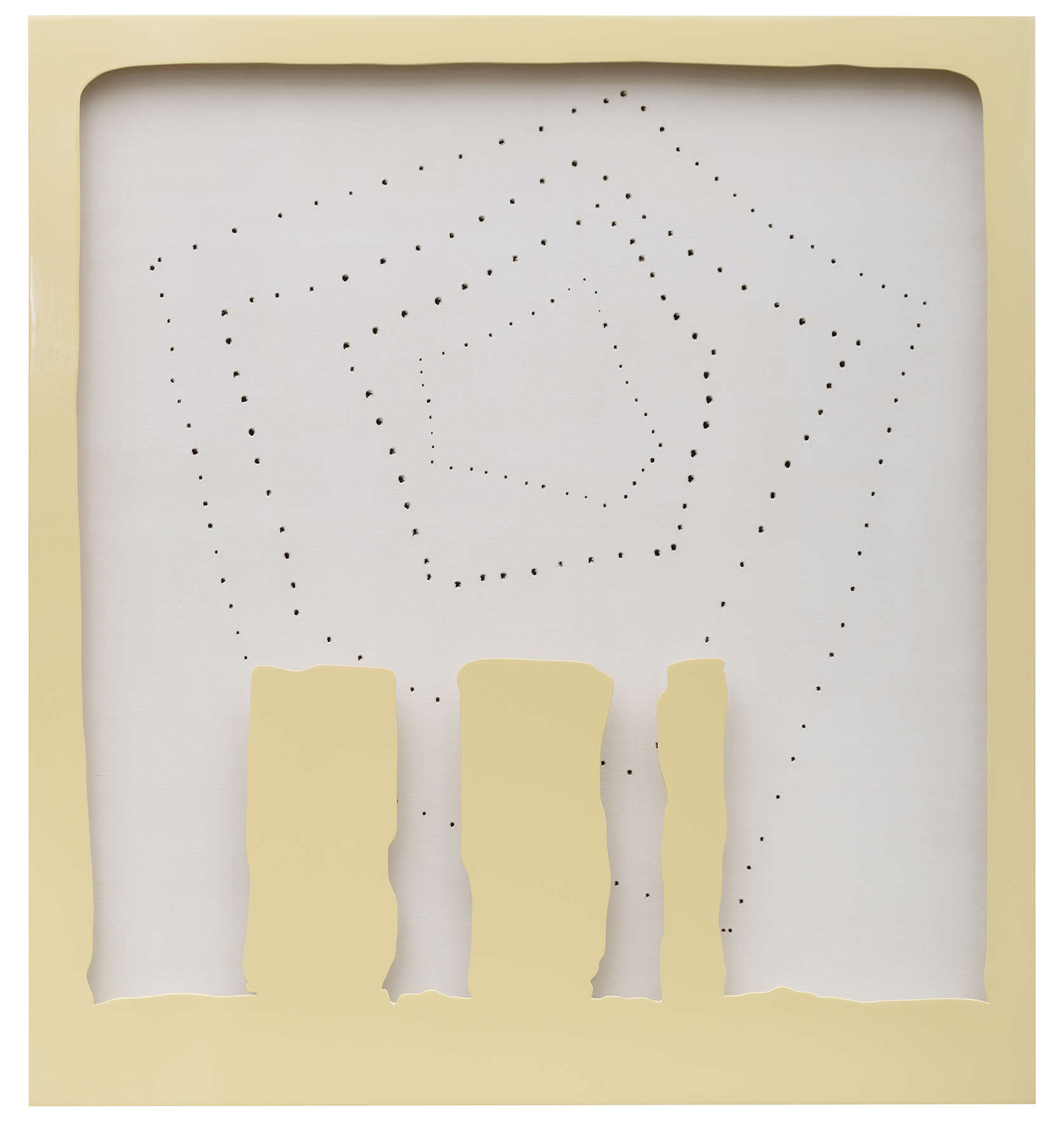

Bandera invites us to read Morandi’s still lifes with bottles "keeping in mind the cut-out silhouettes that stand out before the backdrop of the uniformly painted canvas of Fontana’s Teatrini within their spatial box." In both cases, the space between the forms, according to the scholar, acquires a positive value, becomes a place of tension and expectation.

Morandi’s relationship with modernity is, moreover , complex and never taken for granted. Giorgio Morandi himself, as he would declare in an interview, said he was “strongly aware of the new developments in art in France” and saw Cézanne as an indispensable point of reference. However, his modernity is not exhausted in the assimilation of foreign models, but is expressed above all in his ability to “locate space” in an autonomous and original way, as demonstrated by his attention to intervals, pauses, and silences between forms. It is in this dimension that Morandi’s painting becomes a contemplative experience, a place of access to a deeper and ineffable reality.

If Morandi works by subtraction, Fontana intervenes by laceration. His radical gesture, cutting and piercing the canvas, breaks with pictorial tradition to open the surface to a new dimension: real, three-dimensional space, inhabited by emptiness and light. Fontana himself called himself a researcher, including Morandi in a pantheon of Italian artists (such as De Chirico, Sironi and others), “perhaps not modern but always part of a tradition,” as he called them, artists from whom to start again for new explorations. It was one of the rare occasions when Fontana quoted Morandi, according to Bandera’s research: the phrase is from a conversation with Tommaso Trini held in Cernobbio on July 19, 1968. The distance between Morandi and Fontana, though born in the same decade, is also a distance of worlds and goals: “two different ’worlds,’” Bandera says, “and constantly changing, so that they cannot find an evolution of equal pace, let alone a direct encounter.”

In the 1930s, both frequented the Galleria Il Milione in Milan, a point of reference forItalian abstractionism, and found themselves, albeit on different planes, protagonists of the postwar art scene. Fontana, at the time active as a sculptor, participated in group shows and forged relationships with artists such as Licini, Melotti, Soldati and Veronesi. Morandi, on the other hand, saw his autonomy of thought and research recognized, so much so that he was consecrated by Longhi as “one of the best living painters in Italy.” In the post-World War II period, while Fontana signed the Manifestos of Spatialism and presented his first Spatial Concepts, Morandi was awarded a prize at the Venice Biennale and chosen to represent the Italian 20th century at MoMA in New York for his work dating back thirty years. However, his research had not crystallized, but continued with a succession of works attesting to constant insights.

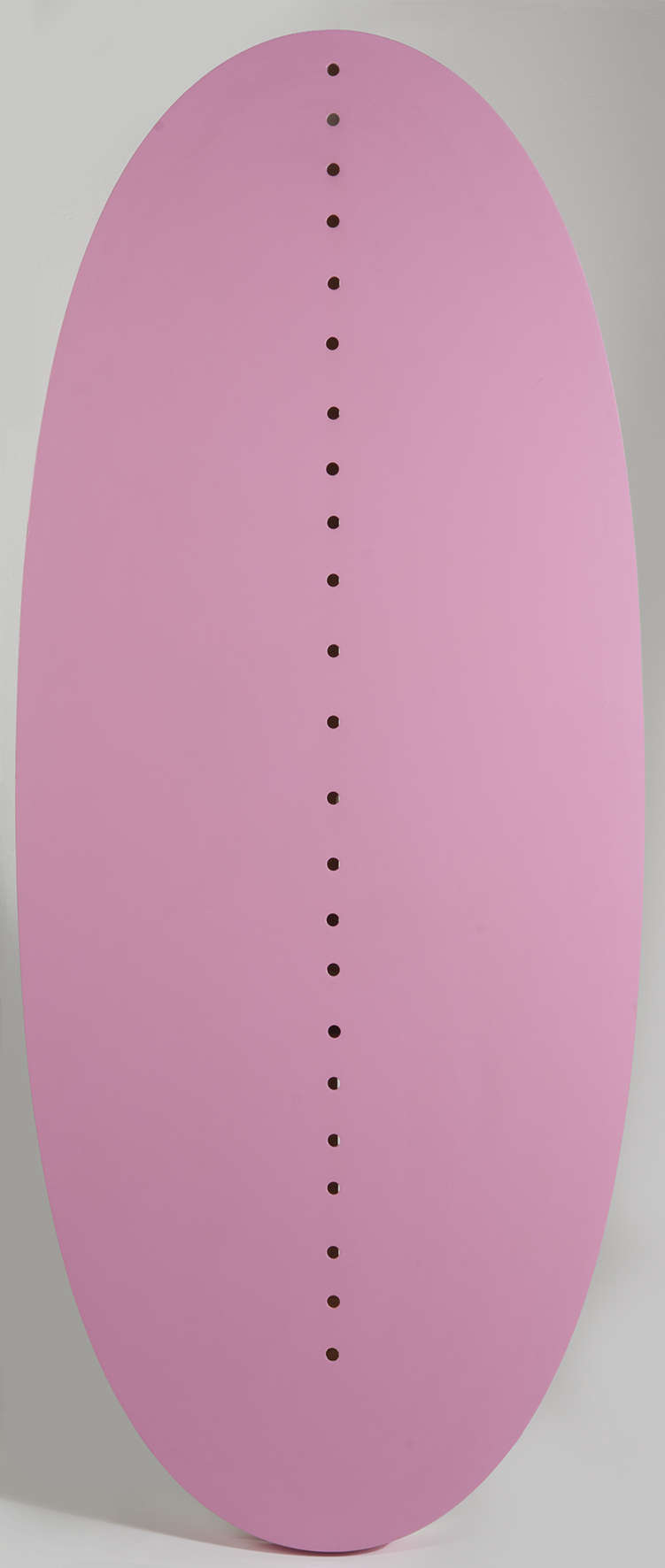

In his Spatial Concepts, Fontana transforms the canvas into a portal, a gateway to infinity, where the void is not absence but substance, the site of manifestation of aesthetic experience. The cut, the wound, thus becomes threshold and opening, in a tension that, although opposite to Morandi’s, shares the same aspiration to overcome the limits of the visible. Fontana undoes centuries of painting and proposes a new conception of artistic space: a real, three-dimensional space inhabited by light and emptiness. Emptiness, in Fontana, is not absence but substance: it is the space where aesthetic experience takes place, the place of the infinite that manifests itself through the wound, the interruption, the threshold.

In his later works, such as the Teatrini, the Concetti Spaziali with stones or porcelain, and the canvases of the Fine di Dio series, Fontana deepens this quest. Materials are enriched, matter expands and multiplies, but the essence of his work remains unchanged: to seek the absolute through the radical act, to transform painting into a conceptual and spiritual dimension.

The juxtaposition between Morandi and Fontana, as Bandera observes, did not arise from a real frequentation or direct mutual influence, but from a “cultural distance and reach that was already palpable from the moments when they must have known about each other.” Yet it is precisely this distance that makes the confrontation fruitful: Morandi interrogates form and time, Fontana space and surface. Both, however, measure themselves against tradition and overcome it, redefining art as an experience of the absolute. In both cases, the space between forms acquires a positive value; it becomes a place of tension and expectation.

Morandi and Fontana, while moving along divergent paths, lead us to the same destination: the beyond. Morandi does it with the slowness of repetition, with mental light and with the silence of his motionless objects. Fontana does it with the energy of gesture, with the tearing of the canvas, with the force of an idea that breaks form to bring out the infinite. Two opposing languages, one desire: to overcome the limits of the gaze, to offer a renewed vision of the world, of art, of reality. To compare Morandi with Fontana is then to propose a dialogue between two visions that revolutionized the way of understanding matter and space.

It is no coincidence that both artists have become indispensable references for generations of contemporary artists, not only in Italy but all over the world. Their legacy manifests itself today in multiple forms: in conceptual art, in minimal art, in abstract and analytical painting, in practices that interrogate emptiness, time, seriality, and contemplation.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.