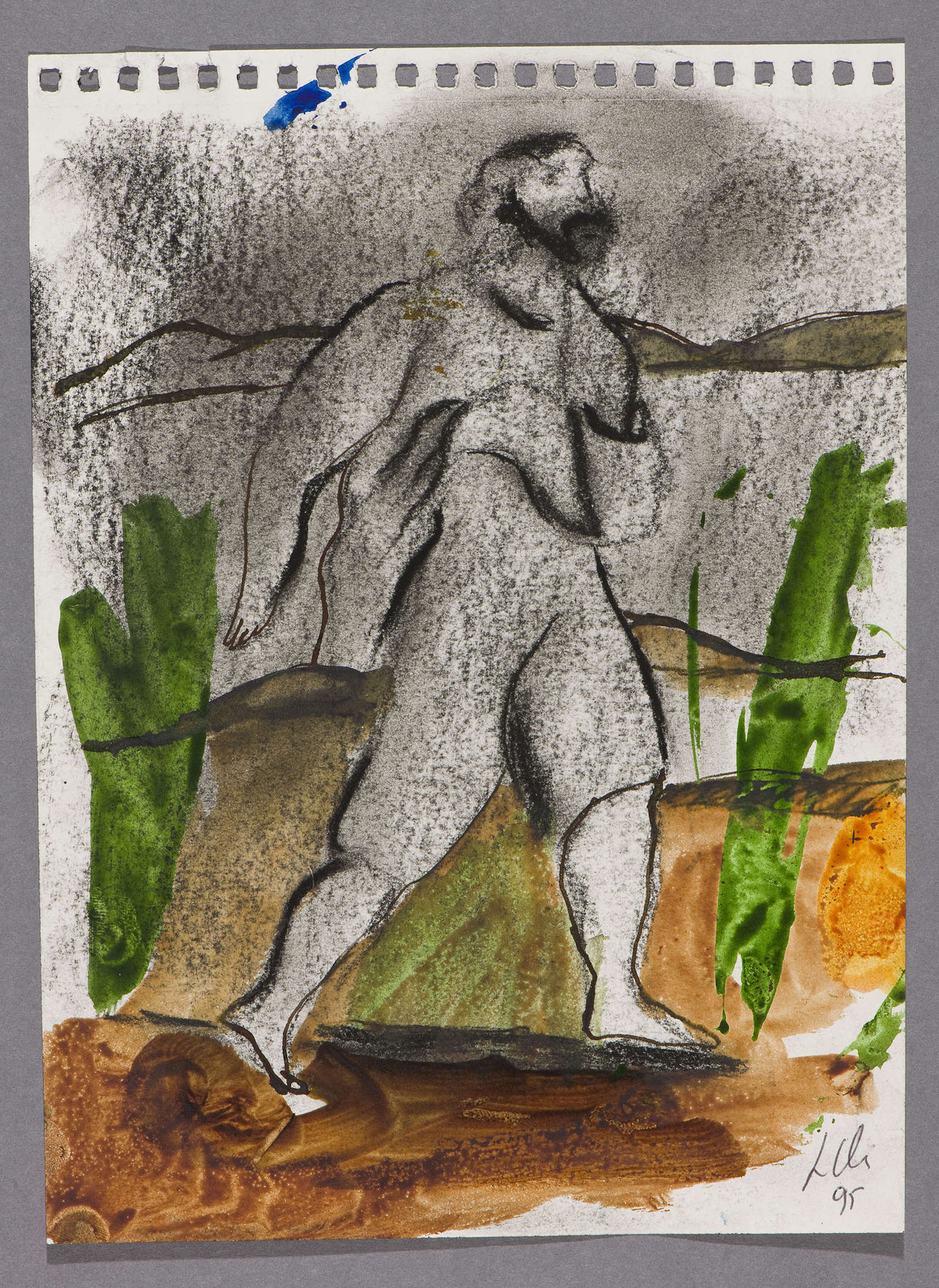

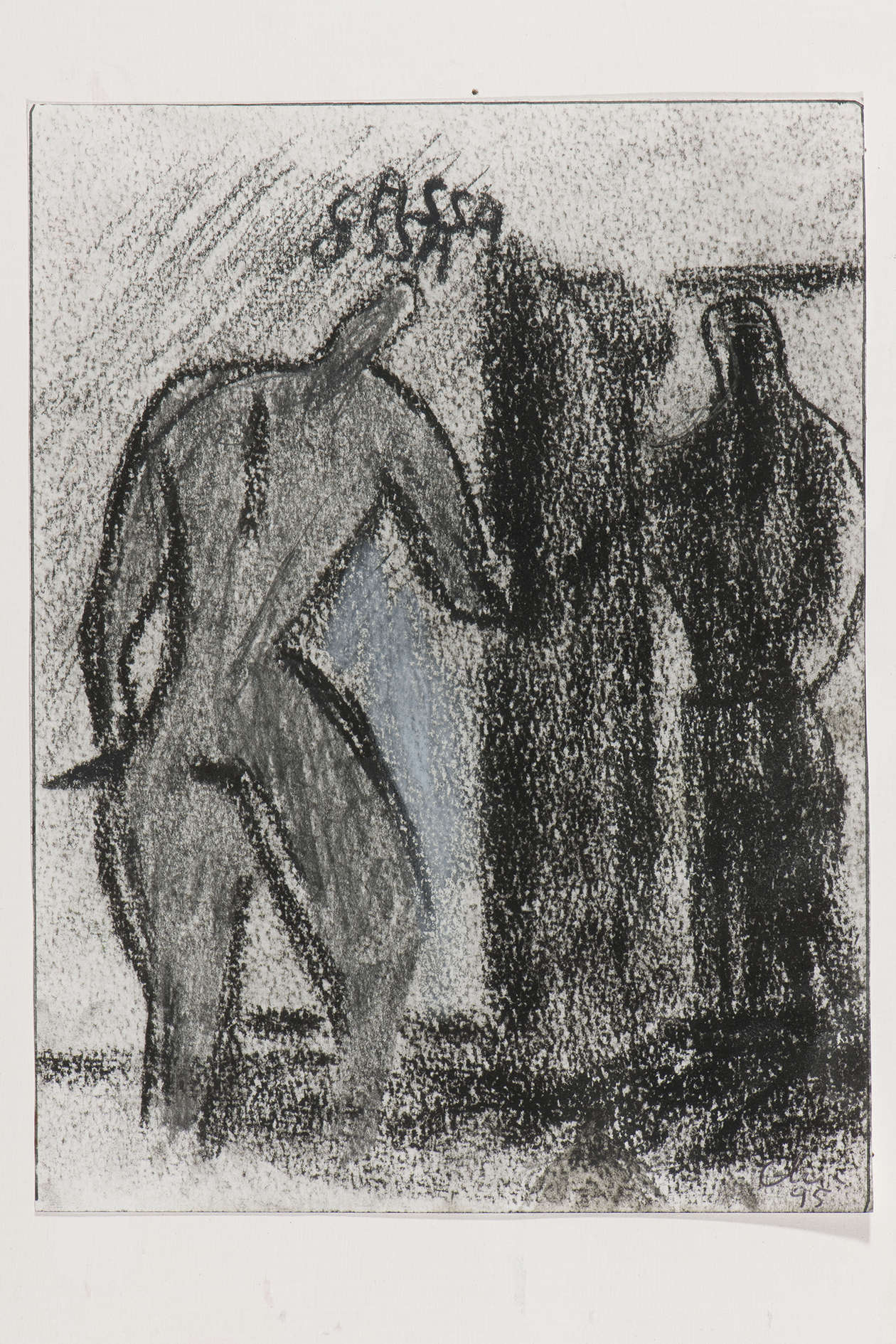

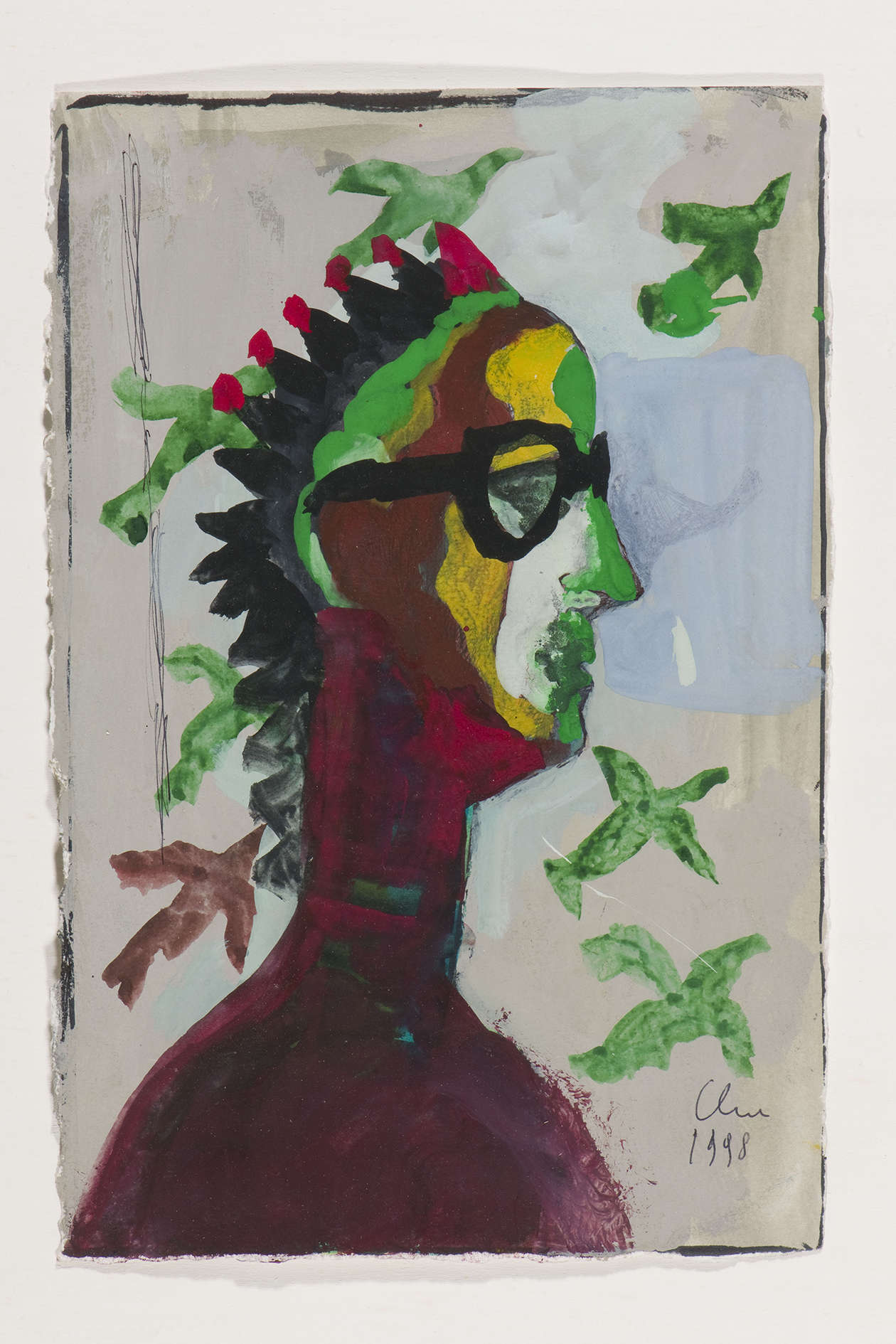

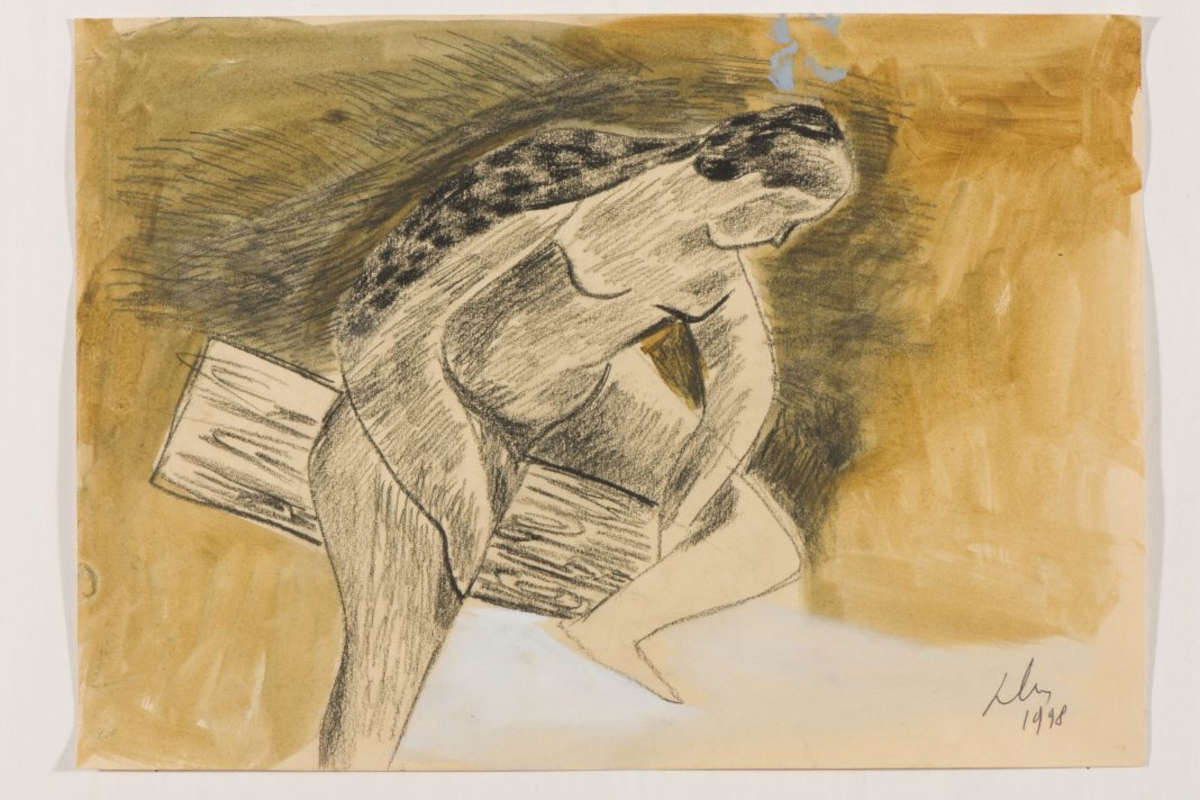

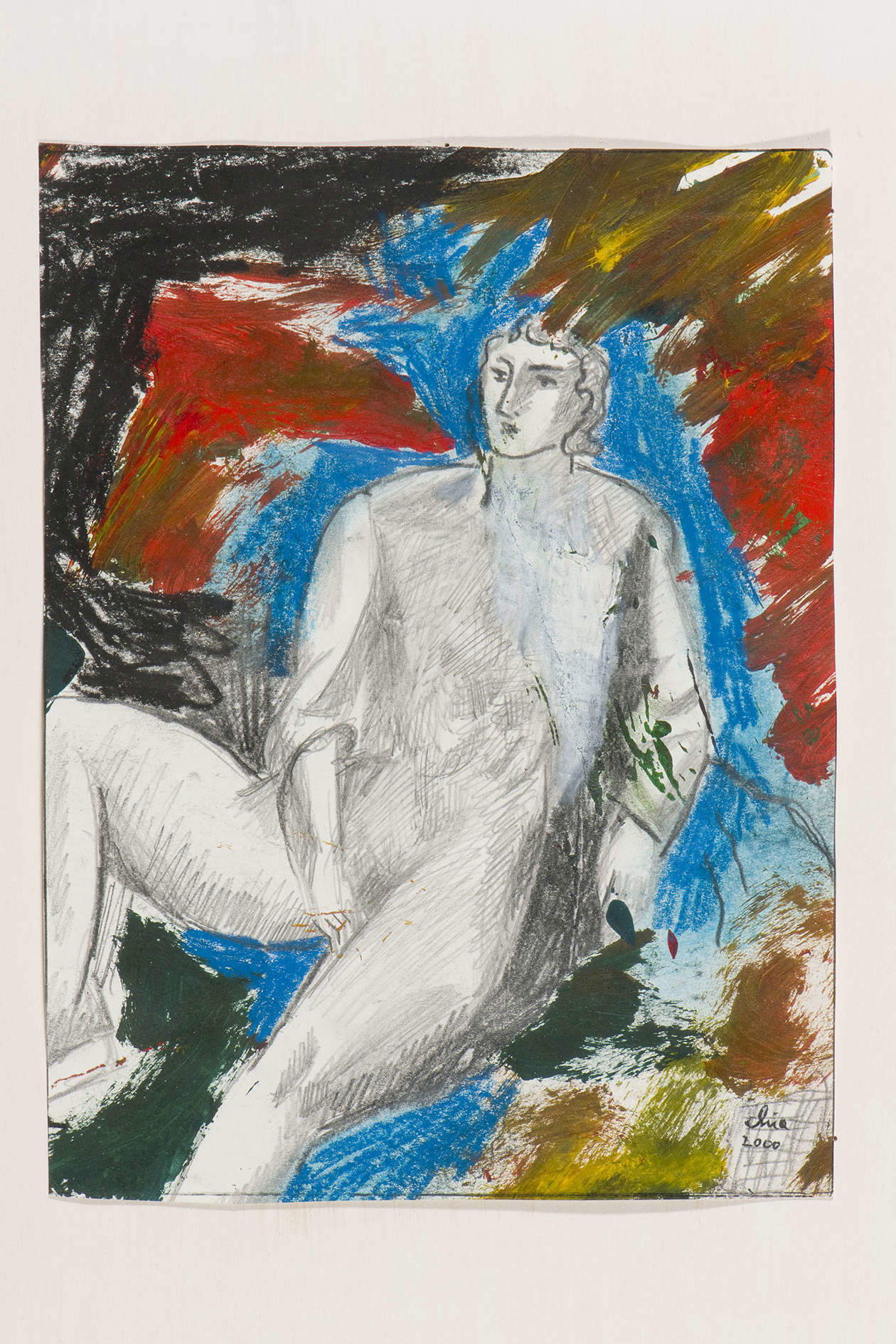

In the complex and stratified artistic career of Sandro Chia (Florence, 1946), paper has never been a mere secondary support: this thesis is also at the center of the recent exhibition Sandro Chia. The Two Painters. Works on Paper 1989-2017 (Lecce, Fondazione Biscozzi | Rimbaud, from February 22 to June 15, 2025, curated by Lorenzo Madaro). Paper is an often little considered area of Chia’s art, but for the Tuscan artist it turns out to be crucial.

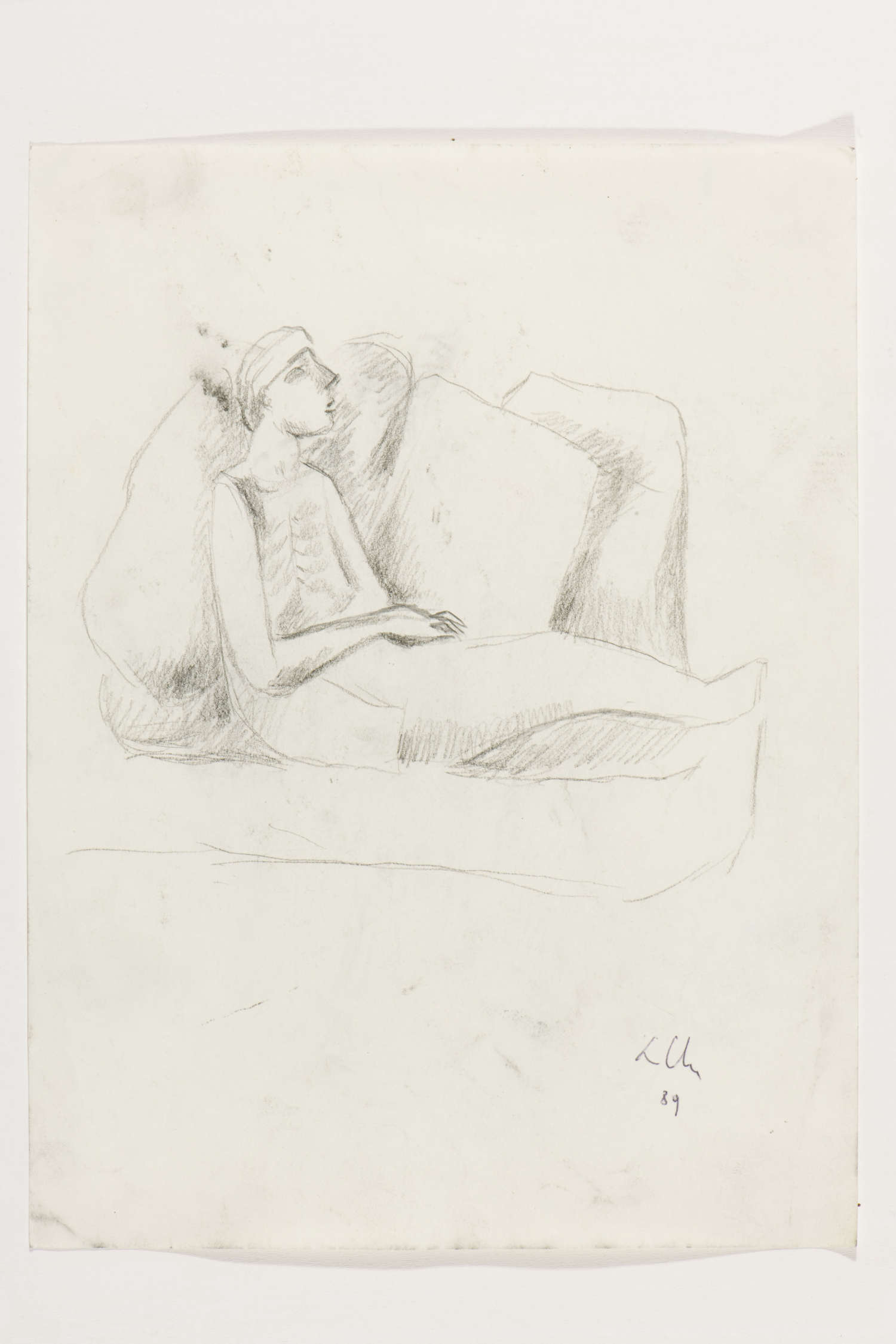

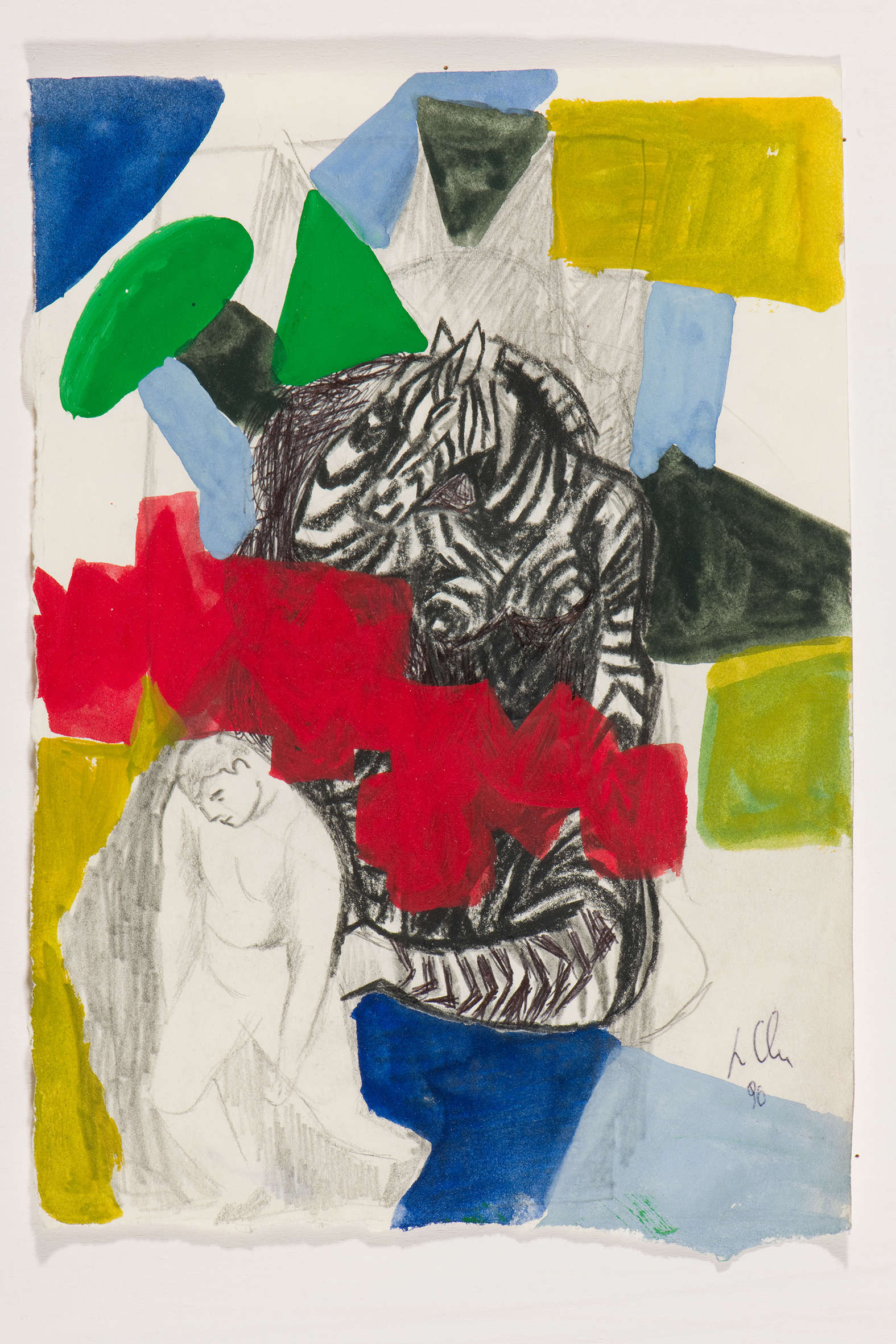

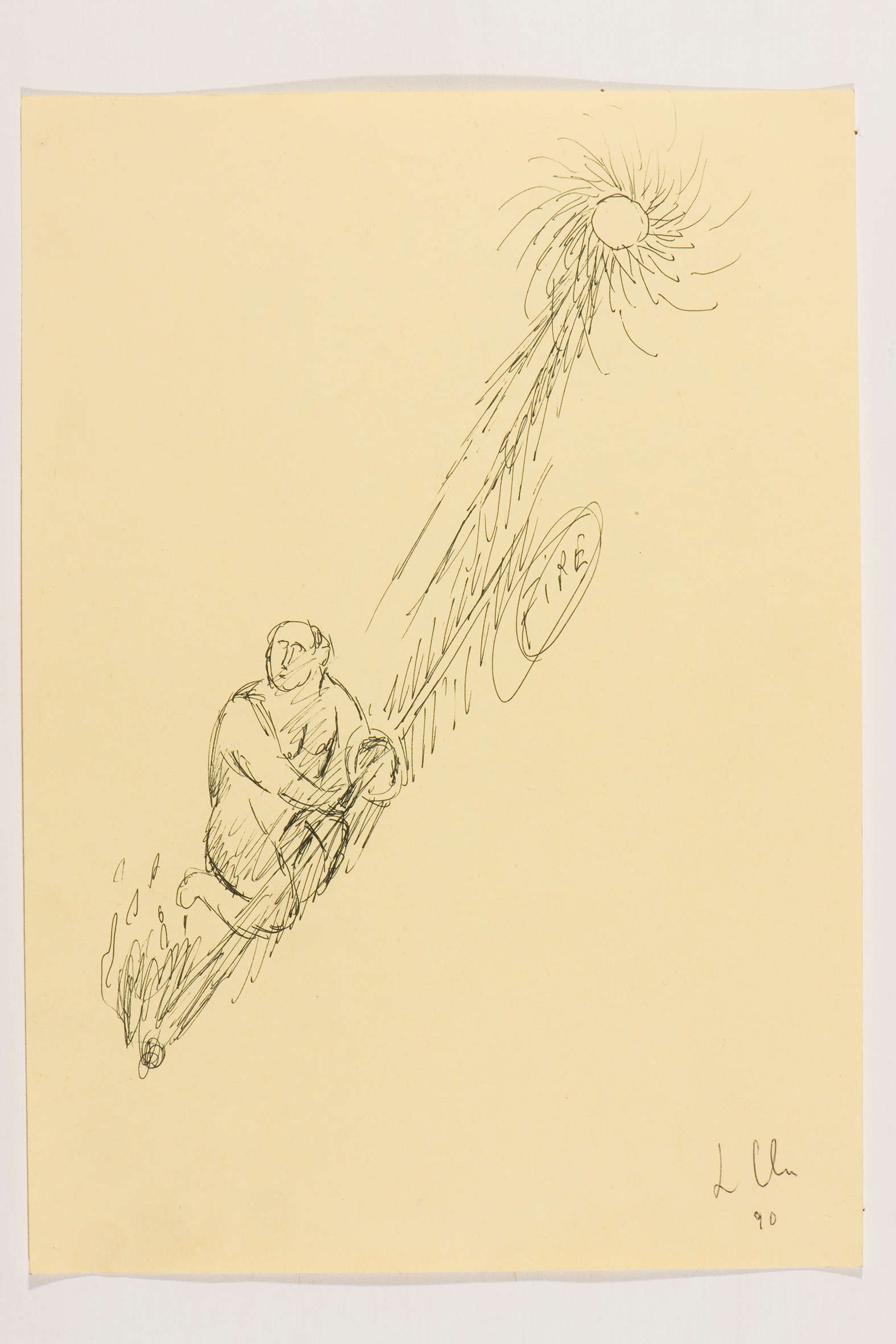

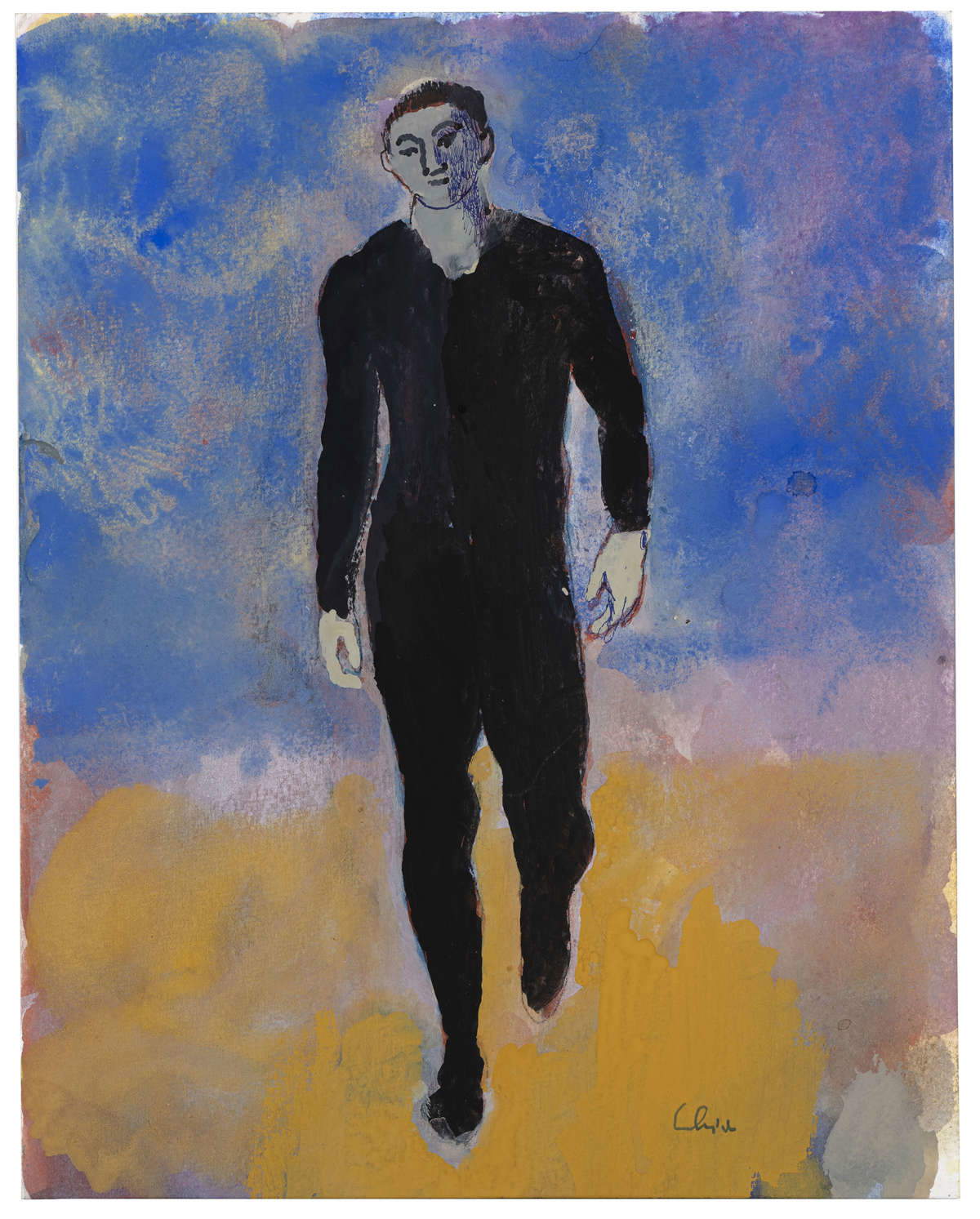

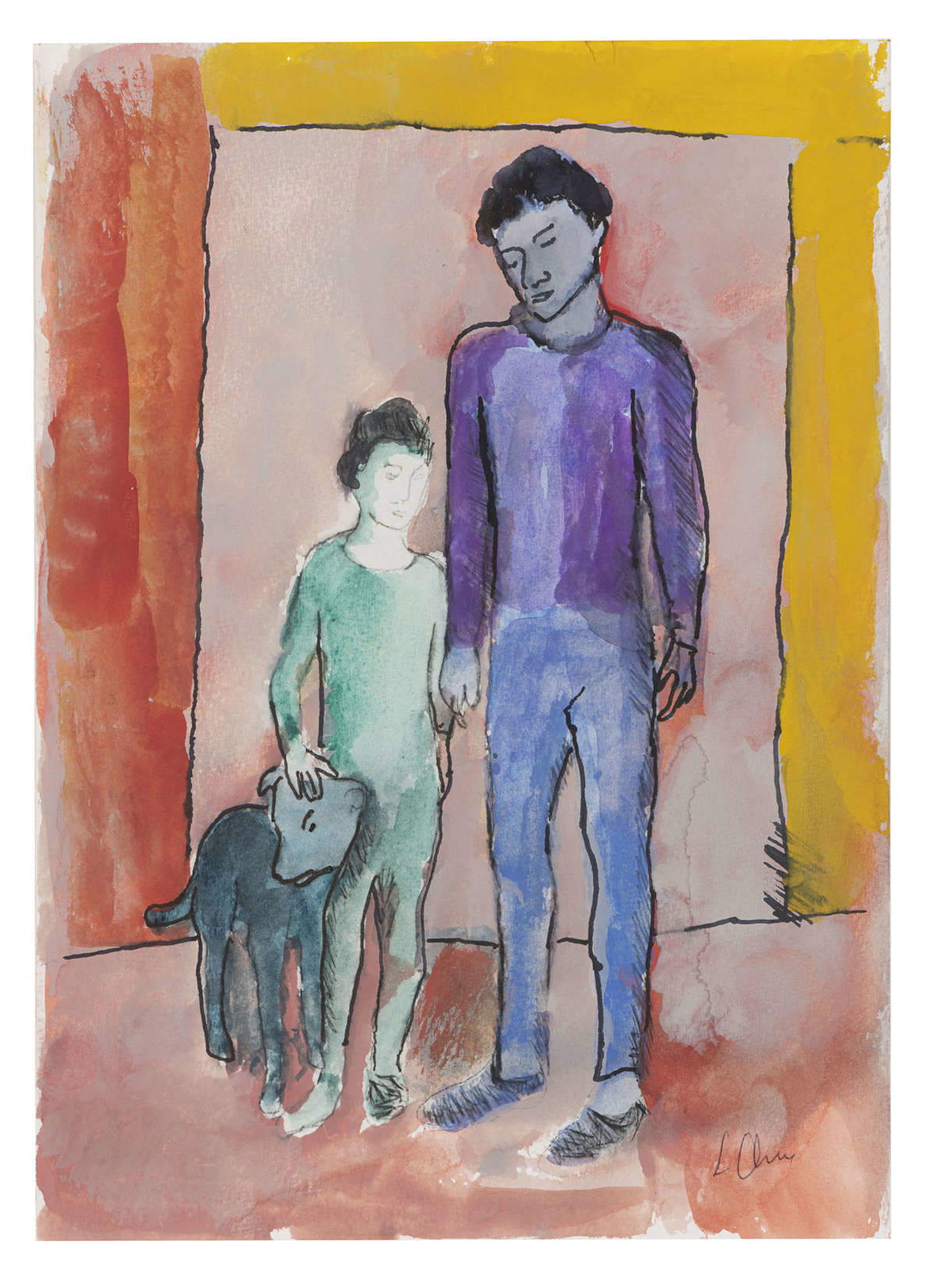

Work on paper is a territory that Chia has frequented with continuity and autonomy, alternating materials and techniques (gouache, tempera, pencils, inks) without ever treating it as apreparatory exercise. Rather, it is on paper that that visual and narrative density that has always accompanied his research manifests itself with more immediacy: bodies, masks, allegories, grotesque and caricature scenes, landscapes of memory and disillusioned visions, all mingle in a flow that, however unstable, appears perfectly consistent with the artist’s identity. “Looking at Chia’s long Italian and international history,” writes Lorenzo Madaro, “one realizes that this medium has been a privileged sphere compared to the coeval production of other cycles consecrated in Italian and international exhibition palimpsests.” Chia is “an artist who does not care about the ordinary time of things, but rather about the time of man in his most intimate but also most universal sphere, because he is a humanist artist, able to speak to men about themselves, thanks to those ecstatic and dynamic bodies and those faces at once monumental and sweet that have accompanied his images for about forty years.”

Chia, born in 1946, arrived in Rome in 1970 from a Florence already marked by tensions between classicism and experimentation. His first exhibition at La Salita gallery, in 1971, marked a start still immersed in conceptual dynamics, but already imbued with a need for image and figure that was making its way underground. “I was in the realm of painting without saying it. Painting at the time ... there was the death penalty,” he would declare years later. In those years, in an environment still dominated by the severity of behavioral and poverist art, the act of painting might have seemed out of time. Yet Chia began even then to search for a language capable of combining vision and concept, irony and construction, gesture and narrative.

Paper, in his case, presents itself as an intermediate, porous space where these tensions can be more freely inhabited. Far from being sketches or rehearsals, Chia’s works on paper are true completed works. It is on this support that his imagination can deform, condense, stylize, without worrying too much about the finish. Nor is it a formal exercise: paper is the place where Chia continually questions the images he elaborates, putting them back into circulation, layering them, transforming them.

In the historical context in which Chia establishes himself, painting (the one understood in the classical sense) seemed by then to be an outdated language, so many have repeatedly given it up for dead. Yet, between the late 1970s and early 1980s, a small group of Italian artists - including Chia, along with Enzo Cucchi, Francesco Clemente, Mimmo Paladino, Nicola De Maria - began to restore centrality to the figure, to narrative, to color, without renouncing the theoretical weight and critical awareness of the previous years. This is Transavantgarde, defined and accompanied by the thought of Achille Bonito Oliva, who emphasizes the desire of these artists to move in a “labyrinth,” digging into the very matter of the image.

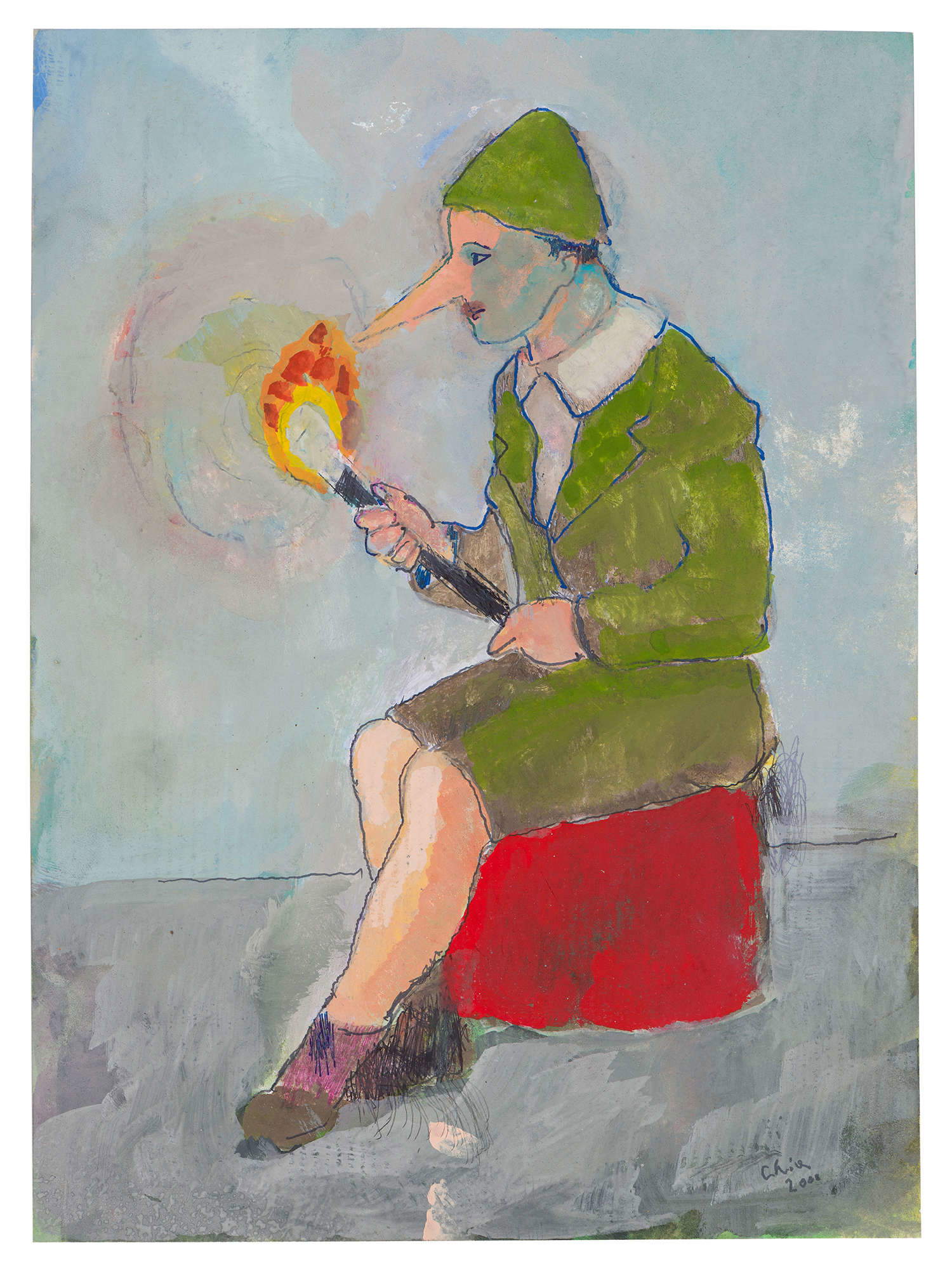

In this context, drawing and paper become privileged tools. For Chia, in particular, this is neither a nostalgic return nor an academic surrender: his relationship with the art of the past - from the fourteenth-century to the avant-garde - is one of recognition and deviation, ironic appropriation, clashes and rewriting. Figures, even the most iconic, are broken down, theatricalized, pushed toward a tone that is never purely epic, but neither is it reductively comic. One thinks of his Pinocchio, an emblem of metamorphosis and ambiguity, a creature uncertain between childlike drawing and existential tragedy that lives even, and perhaps especially, in works on paper.

In Chia’s graphic corpus, his introspective gaze becomes instinctive and programmatic at the same time: the characters, the lovers, the loneliness, the almost pantomime-like gestures, are pieces of a repertoire that mirrors human time rather than the chronicle. Because Chia is not interested in representing historical time, but the inner, collective, archetypal time. In this sense, paper becomesa place of revelation and at the same time of instability, where everything can change: strokes lengthen, colors brighten, anatomies deform, expressions become grotesque or melancholic. And each stroke is at once a tale and a questioning of the tale.

This continuous work on the image (which is almost never merely illustrative, but always charged with semantic tension) has allowed Chia to build, over time, a solid but never static imagery. There are many souls to Chia’s drawing, as well as to the artists of the Transavanguardia, as Bonito Oliva himself recognized in the past, writing in the catalog of the 1980 Transavanguardia exhibition held at the Kunstverein in Bonn: “Drawing in the works of Chia, Clemente, Cucchi and Paladino is sign, frieze, image, effigy, line, sketch, arabesque, landscape, plan, diagram, profile, silhouette, vignette, illustration, figure, foreshortening, print, cutaway, sketch, cast, caricature, chiaroscuro, graffito, engraving, map, lithograph, pastel, etching, silography. The tools can be: charcoal, pencil, pen, brush, pencil, compass, puller, square, pantograph, ruler, ruler, gradient, stencil. The process can be: arabesque, limestone, compose, copy, erase, correct, polish, derive. The result: field, outline, shadow, ornament, perspective, hatching.” The reference to drawing as a central element in Transavanguardia, well described in Bonito Oliva’s theoretical texts, finds an excellent example in Chia. In his works on paper, in fact, drawing is not just a line or a tracing: it is a way of thinking with the hands, and the variety of tools employed testifies to a practice that is both analytical and instinctive.

Paper, then, is for Chia a territory of freedom, but also of challenge. A place to measure oneself with the memory of art, without ever being subjected to it, and with one’s own imagination. The value of Chia’s work on paper lies precisely in showing instability as a figure of coherence, in proposing a layered and nonlinear reading of an artist who has always refused univocal paths.

Today, having returned to his Tuscany after years spent between New York and major international galleries, Chia continues to work on paper with the same energy and irony that have always distinguished his work. And in his work, paper becomes a map of his visual thought, a living archive of figures that speak to man about himself, without definitive answers, but with the urgency to keep imagining.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.