Just over forty years ago, the rooms of PalazzoRealeaMilan hosted the celebrated exhibition The Other Half of the Avant-Garde 1919-1940. Women Painters and Sculptors in the Historic Avant-Garde Movements, which constitutes a milestone in studies interweaving art history and gender issues. Through a selection of more than one hundred works by women artists belonging to the avant-garde movements of the first half of the 20th century, Lea Vergine, an art critic who recently passed away, attempted to offer a counterpoint to the art history of manuals, which continually recorded only male artists, omitting the gigantic contribution in the development of women’s art movements. Since that 1980, many studies have come up onwomen’s art, although much still needs to be done, with the aim of redefining the role of the woman-artist within the too-masculine art world. But little attention has been paid to female art criticism.

This is the only way to explain why so many names of absolutely outstanding personalities have been lost in the folds of history. Among them, a prominent role should be reserved for Anna Franchi (Livorno, 1867 - Milan, 1954), writer and art journalist, author of more than sixty publications and countless essays, playwright, musician, but also activist, moved by a complex social conscience that led her to fight for so many causes, especially women’s rights. A very long life traversed by two wars, many griefs and sorrows, but still so many things to tell, so many that in one article it would be a difficult undertaking. Fortunately, she succeeds at least in part, but masterfully, in her autobiography La Mia Vita (Garzanti, Milan 1940), a text really worth reading.

Anna Franchi’s out-of-the-ordinary life began in Livorno in 1867, a city that was always dear to her and where, in fact, she herself wanted not only her body to return, but also her literary efforts, books, notes, correspondences with artists and other intellectuals, and many other testimonies of her volcanic personality. This immense material is preserved at the Labronica Library, and constitutes a fund of great interest and indispensable for the reconstruction of the life of this extraordinary character.

Anna Franchi grew up in a wealthy environment of progressive and Mazzinian ideas. She began her adult life while still a teenager, marrying Ettore Martini, a violinist and conductor, in 1883 at the age of sixteen. From early on she clashed with the social impositions placed on women, made up of imposed expectations, limitations, and having to continually stifle her own ambitions in order to fulfill the task of the mother of the family. The ill-combined marriage union soon proved to be a cage with a violent and faithless man, and the relationship finally foundered when her husband moved to Philadelphia. It was then that Anna Franchi had to come to terms with a woman’s subordinate role even before the law: in fact, she could not administer her own property independently since the Civil Code did not allow married women to manage economies without marital authorization. In response, Anna fought to have more rights recognized for women, became involved in the Socialist Party in Florence, and in 1902 wrote the novel Avanti il Divorzio (Sandron, Milan). With effort and accepting many work compromises, she managed to support herself and her family, including her mother, through writing. She wrote in several newspapers and in 1900 was admittedto the Milan Register of Journalists, preceded only by another woman, Anna Kuliscioff, Filippo Turati’s companion. She wrote novels for children such as I viaggi di un soldatino di piombo (Salani, Florence 1901), but also passionate irredentist reflections such as Città Sorelle (Treves, Milan) in 1915. Then a new lacerating grief: his beloved son Gino died on the front. Nevertheless, her civic passion did not wane and she founded the League of Assistance among the Mothers of the Fallen, which gained her some notoriety and a provisional permit to drive, at the time inhibited to women. With fascism her public engagement and literary activity ended; she was forced to keep away from the political battle, supporting herself by writing unwillingly in beauty magazines. Later, she participated in the Resistance.

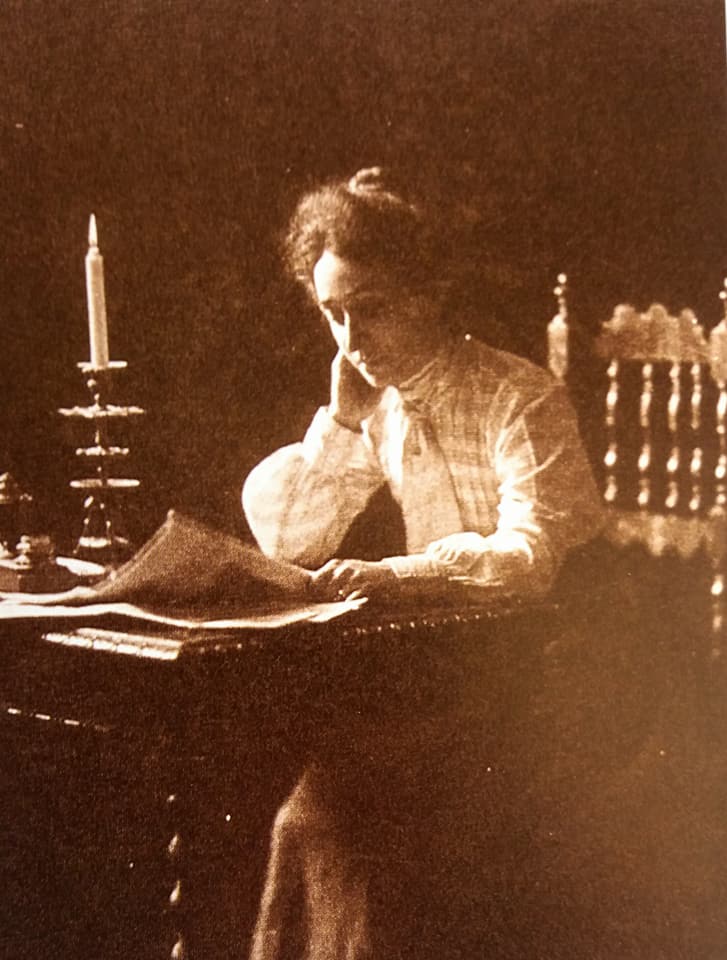

|

| Portrait of Anna Franchi, F.lli Alinari, circa 1895 |

|

| Anna Franchi while painting, circa 1905 |

|

| Anna Franchi in her studio |

|

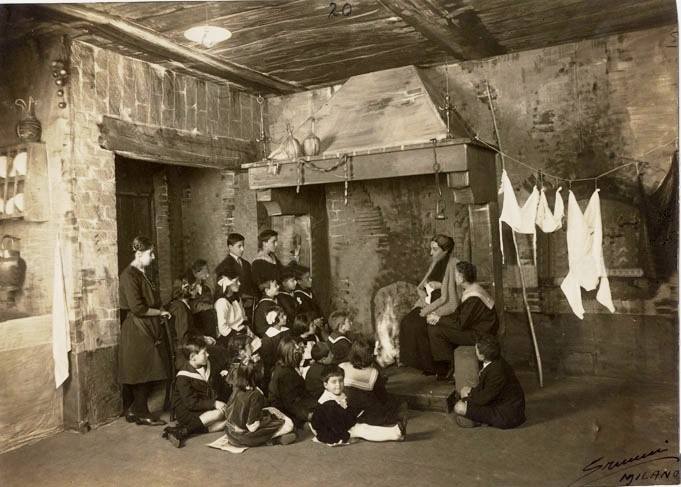

| Anna Franchi narrates novellas to a group of children, circa 1915 |

|

| Anna Franchi with journalist and politician Ettore Janni, 1953 circa |

But Anna Franchi deserves to be remembered not only for all these activities, but also for her involvement in the art world. A friend of artists thanks to her frequentations of the Tommasi painters’ villa, she became a militant journalist and art critic, sales intermediary, correspondent and lecturer. In this activity, too, she had some notable firsts that are worth exploring. First of all, she was genuinely passionate about art, so much so that despite her history with her ex-husband, in love with his art, she tried even after the latter’s death to enhance his creations, feeling a duty to safeguard that artistic genius, which had bewitched her, but was wasted behind a dissolute life.

It was said before of the friendship with the Tommasi family, which was the conduit for the writer to get to know a close-knit group of painters, almost all of Tuscan origin: the Macchiaioli. In 1883 Franchi and her husband spent their honeymoon in Florence at the home of the Tommasi family friends, particularly Lodovico, who studied violin at Livorno from her husband Ettore. On that occasion, Franchi got to know Silvestro Lega, the Tommasi’s master: “Romagnolo un po’ sgarbato[who]had the art of coloring a tale with a brushstroke,” Telemaco Signorini “finely sarcastic” and Giovanni Fattori “simple and confident,” and then all the others “poor all, glad almost of their misery.” “Outspoken rebellious personalities [who] were a revelation I was never to forget again,” she would write in her biography. A few years later, when her husband was called to conduct an orchestra in Florence, the family followed him, giving Franchi an opportunity to get back in touch with “survivors and new” artists. In that group, so irreverent and free of traditions and convictions, the writer found not only a group of friends but also an example: “how good the example of their faith, of their playful resignation to misery, did to my soul.”

In the artists’ studios, during their exhibitions and during evenings in their company, Anna Franchi talked about art, confronted each other, learned anecdotes and memories that the old Macchiaioli entrusted to her as if they were precious secrets, almost foreshadowing the role of historical memory she would play for the group. “It was after ’95 that Signorini’s friendship encouraged me to write about art”: indeed, it was in the 1990s that she began her work as an art critic and journalist. He wrote in several newspapers including La Nazione, La Settimana, La Domenica fiorentina, and Il Secolo XX as a correspondent from major international exhibitions, and from 1897 he covered the Venetian Biennials. It was Signorini again, perhaps the most learned of the clique, who, after reading an essay of hers on Segantini, asked her to take charge of a book that was to collect the memoirs of the Macchiaioli artistic movement, and Franchi agreed. The news was immediately greeted with great enthusiasm by the various artists, who perhaps saw in a publication a kind of revenge on the system that had always sidelined them. “If she does this book, it will be more consolation to me than a cross, because these will be the words of a friend,” Fattori told her. In 1902 Anna Franchi finally gave the prints Arte e artisti toscani dal 1850 ad oggi (Alinari, Florence), but Signorini unfortunately could not read it: in fact, he died the previous year. The book gained much praise.

|

| Anna Franchi with her son Gino Martini Franchi, who died in the war |

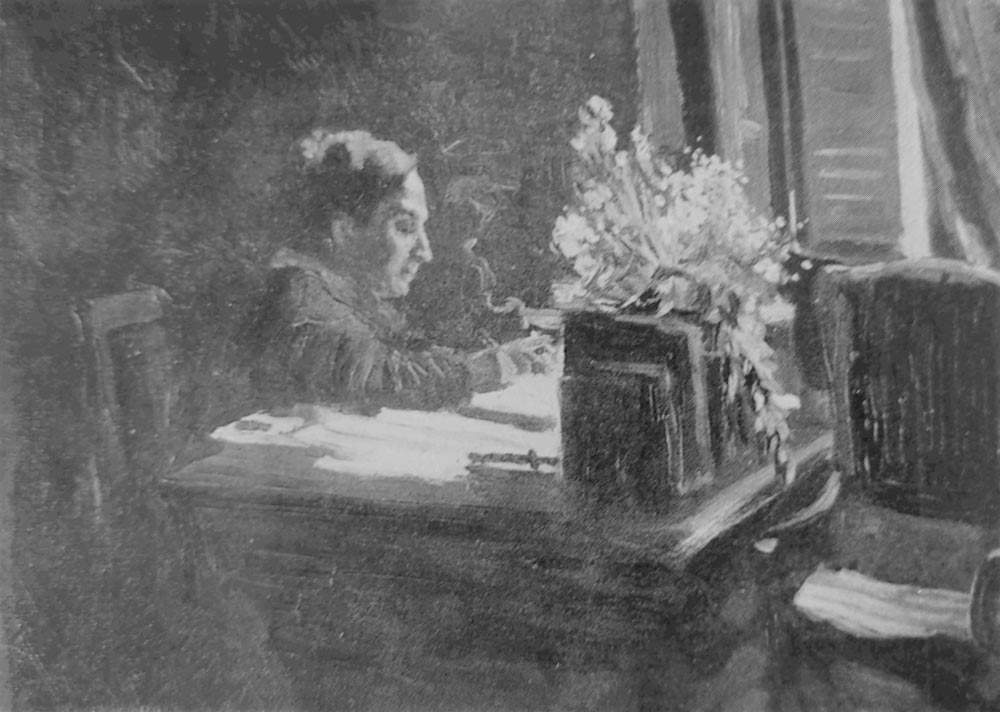

|

| Gino Martini, La mamma al tavolino (sketch executed by his son during his last leave, 1917) |

|

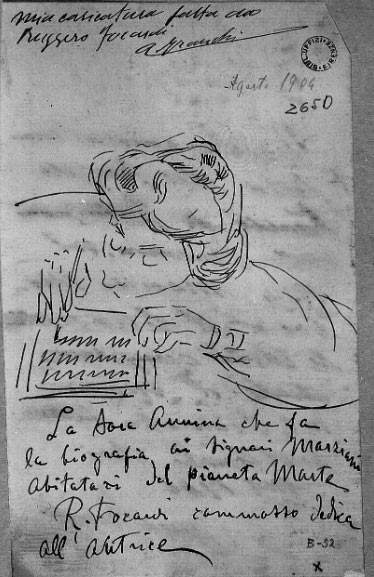

| Ruggero Focardi, Caricature of Anna Franchi (1904; Florence, Galleria darte moderna) |

|

| Giovanni Fattori and Anna Franchi, ca. 1900 |

In 1910 Anna Franchi was chosen along with Plinio Nomellini to commemorate Giovanni Fattori, who had died two years earlier, at the retrospective exhibition dedicated to him, and on that occasion she published with Alinari Giovanni Fattori. biographical study, which can rightly be considered the first biography of the Leghorn artist, and the proceeds of which went toward the cost of a bust dedicated to the master. These critical texts show how Anna Franchi was second only to Diego Martelli, in order of time, in having recognized and believed in the greatness of a handful of artists to whom the market and critics, on the other hand, did not look with as much conviction. Also in the field of art, as indeed in all aspects of his life, the Leghorn critic had a free thought, free of prejudice: “Fortunately, I do not do criticism - for this purpose there are special people to whom free passage was given before the public, so that they could slant to the four winds on the hospitable complacent sheets, their inappellable judgment - on this the people must be informed. It is fortunate, for thus at least remains to the simple lovers of art, the great satisfaction of telling the truth,” he wrote in his lengthy account of the 1905 Venice Biennale.

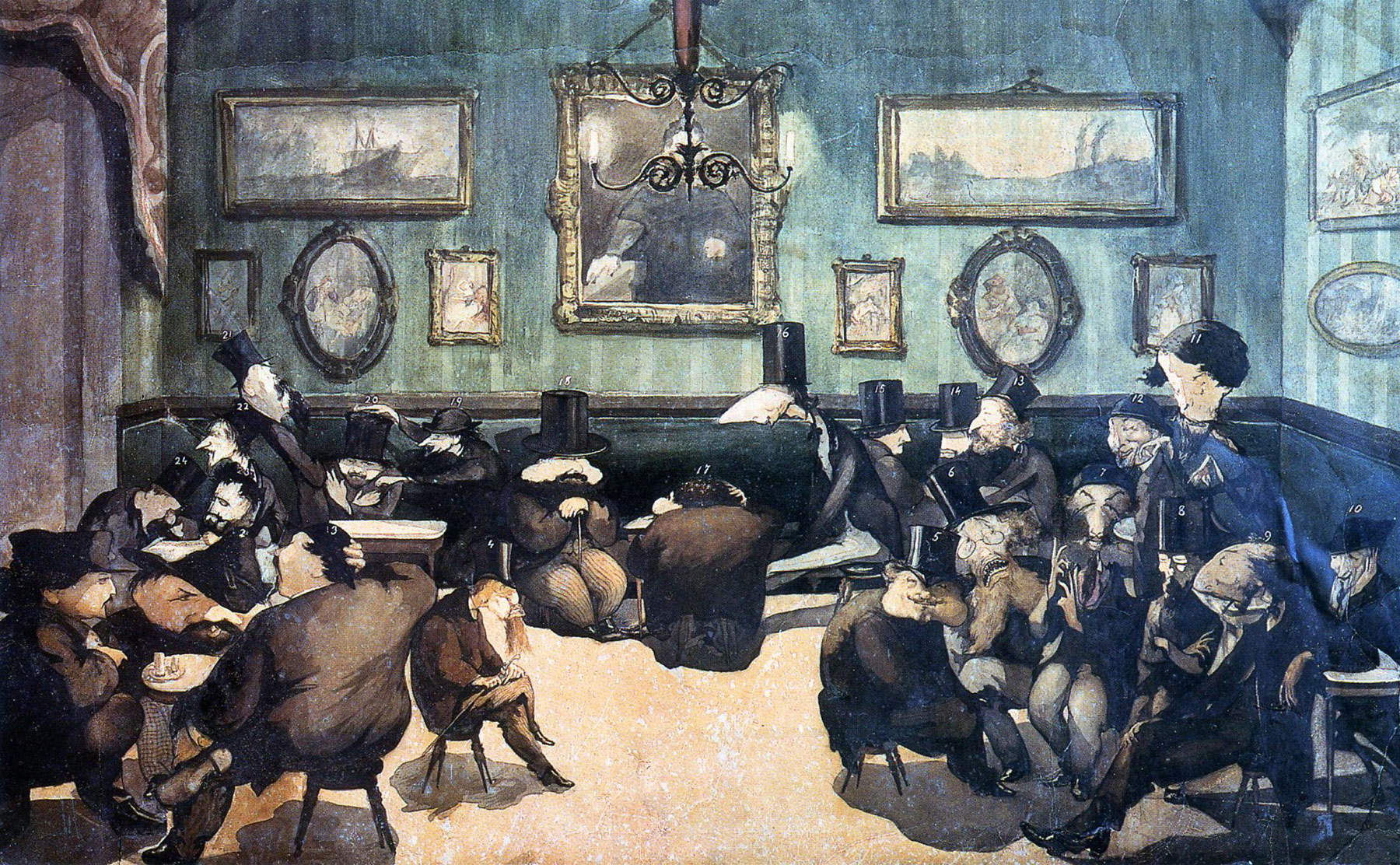

He still devoted many pages to the Macchiaioli in numerous essays and in a chapter of his biography and again in the 1945 publicationIMacchiaioli toscani (Garzanti, Milan). In the texts Franchi evokes the environments experienced by the Macchiaioli, including the Caffè Michelangelo where “amidst the smoke of pipes and jokes” painters and literati united by yearnings for rebellion met. Here, one day, Serafino De Tivoli returned from France, bringing with him the novelties of painting from beyond the Alps and thus becoming “the daddy of the macchia.” But the Café was also a place of jokes and boisterous pranks, which were confided to the writer, who with great care reported them in her books, not only for the pure taste of anecdote but to revive the creative and irreverent climate that always accompanied the Macchiaioli movement.

It is to Giovanni Fattori that Franchi dedicates his most admired words: a painter whose “work is a monument that cannot perish so much as it was born of truth.” For the critics, the Leghorn master is a pure man, in painting as in life, and so they baptize him “the great child,” whose life “was one dazzling narrative, repeated with ever new phrases.” Love of art and sincerity had driven Fattori to refuse all compromise. He was so reserved that when he found out that Anna Franchi was writing a book on the Macchiaioli, he wanted to make sure that not too much was written about him lest people think he was trying to advertise himself; disconsolately he told her, “You know dear friend how much I hate the thing.”

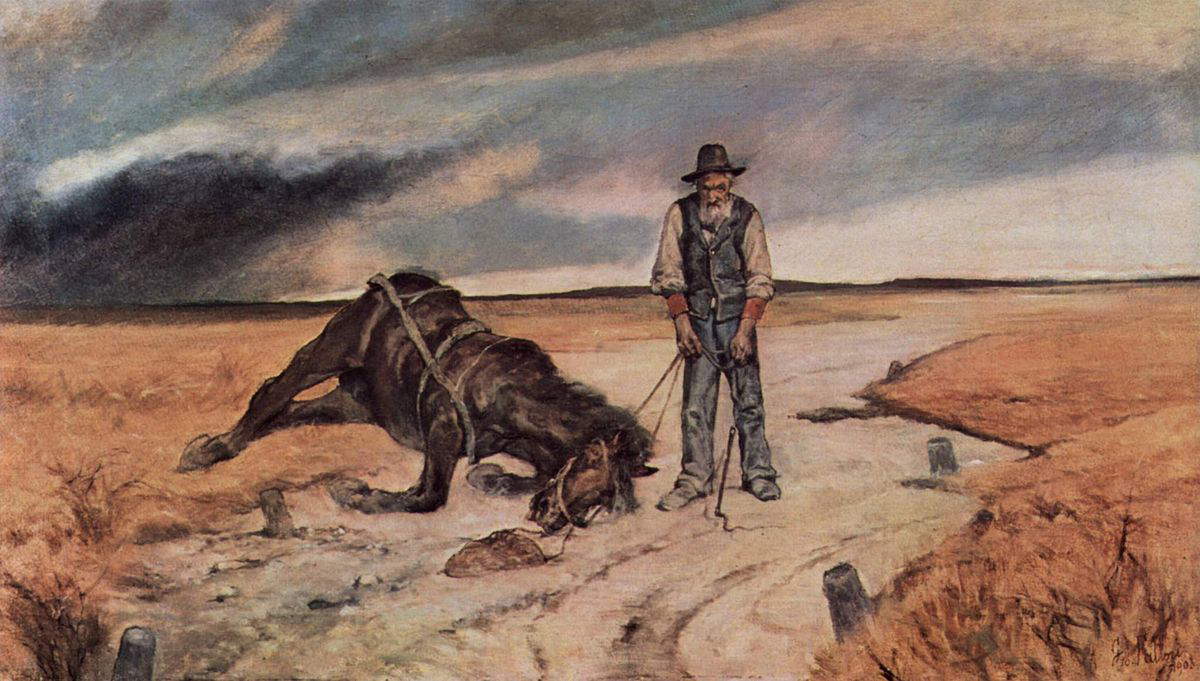

Franchi saw in the Leghorn master that “brutal sincerity in search of light,” and when he wrote that “his hand seems to anticipate thought,” with great acuity he identified the painter’s peculiarity of rendering the truth of nature, not caught in its phenomenal manifestation, but in its essence. Anna Franchi also revealed the painter’s genius in her description of the painting Dead Horse, in which according to her Fattori wanted to express the horror of despair and where despite the apparent simplicity and essentiality of the scene “everything is said and the pain is imprinted in that canvas, not by the four brushstrokes, but by the feeling, by the soul of the artist, almost unconscious of what the hand was tracing.” Franchi attended and assisted the old master until a few days before his death, later writing about it in her texts: Fattori asked her to see Florence from Piazzale Michelangelo, and told her “I will work, it seems to me that I have not done enough [...] ah art, how many things I have not done how many things I have thought! I could have done more.”

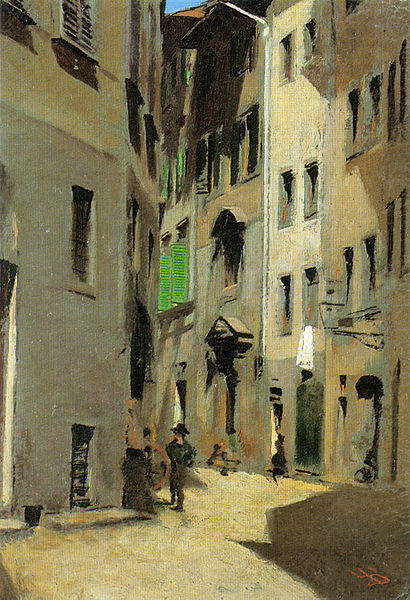

Franchi, with acuity, eternalized not only Fattori, but all the participants in the Macchia. From De Tivoli who rendered in painting “trees made into masses, pierced with brushstrokes, to let the air in,” to Cristiano Banti who procured a black mirror by means of which he could see how to render the stain. Then Odoardo Borrani who “had understood how to stop a ray of sunlight on canvas,” to even the younger ones, such as Ludovico Tommasi who followed the real almost restlessly, “that real that varies with the minute that passes”, and Plinio Nomellini who uses the symbol in the search for truth, for a high and profound concept, and reproduces “the poem that nature sings for him”; or Benvenuto Benvenuti “artist of the human poem.”

Franchi claimed the goodness of that research that started from the Macchia and unravels toward multiple outcomes, but what unites the Tuscans for Franchi is the love for their quiet nature: “They do not have difficult conceptions, they are simple clear narrators of what they observe, without declamatory phrases but with the correct and concise period.” For the writer, the movement’s highest value is that spasmodic pursuit of truth without effects or compromise. That “superb truth of liberation toward which they went confidently and courageously.”

|

| Adriano Cecioni, Il caffè Michelangelo (ca. 1861; watercolor, 53 x 82 cm; Milan, Private Collection) |

|

| Giovanni Fattori, The Dead Horse (1903; oil on panel, 62 x 107 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Telemaco Signorini, Via Torta in Florence (c. 1870; oil on panel, 16.6 x 11.3 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Plinio Nomellini, The Gulf of Genoa or Ligurian Marina (1891; oil on canvas, 59 x 96 cm; Tortona, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Tortona) |

Through his publications the Macchiaioli found affirmation and public fortune, but unfortunately what Telemaco Signorini prophesied was fulfilled: “When we croak we will become famous.” Franchi acquired a certain notoriety so much so that even Matisse spoke of her to journalist Milziade Torelli, stating that her Macchiaioli friends were defended and understood above all by her. The Macchiaioli found in her a trusted ally, and her support did not remain only in print, but she supported the cause of the Tuscan artists in every way, for example with her numerous lectures and, even more directly, as an intermediary with collectors for sales. Franchi carried on this activity, which was of primary importance but difficult to reconstruct, especially in Milan, where the Macchiaioli entered several collections, thanks to her close acquaintance with far-sighted collectors, who, after all, had to prove to be “a little patrons a little passionate.” Anna Franchi’s extraordinary merits as a militant critic were always recognized by the artists, with whom she had long correspondences, in which the tones are always very affectionate. They were true relationships of friendship, such as the one with Nomellini, who called her “dear friend,” or with GiorgioKienerk, who with even more intimacy addressed her with words that ended in good-natured mockery and turpitude. While decidedly colder was the world of Italian art criticism: they often struggled to acknowledge her great merits, so much so that she herself had to claim them publicly: “The first to deal with the Tuscan Macchiaioli was me [...]. Ugo Ojetti came - if anything - after me,” she wrote after the powerful critic, who at first had shown himself rather ill-disposed toward the Macchiaiola and Fattori experience unless he later changed his mind, had dealt with the Tuscan group without citing her among the main scholars.

Franchi’s life, although little known to the general public, has over the years been the subject of a number of important studies, most notably the text Anna Franchi: L’indocile scrittura. Civil Passion and Critical Insights by Elisabetta De Troja in 2016, which outlines Anna Franchi’s extraordinary creative and literary experience, including by focusing on her activity as an art critic. Nevertheless, even among studies and exhibitions, Anna Franchi’s great importance is still often omitted. Not the least proof of this is also the persuasive appellation given to Margherita Sar fatti as “the first Italian and European art critic”: the activity of Margherita Sarfatti, although she was another figure of primary interest on the Italian scene, is in fact placed in the art world at least two decades after that of Franchi. But God forbid we should fall into the same error and attribute Anna Franchi that title, since history is always very sparing in correctly recording the names of great women.

The author of this article: Jacopo Suggi

Nato a Livorno nel 1989, dopo gli studi in storia dell'arte prima a Pisa e poi a Bologna ho avuto svariate esperienze in musei e mostre, dall'arte contemporanea alle grandi tele di Fattori, passando per le stampe giapponesi e toccando fossili e minerali, cercando sempre la maniera migliore di comunicare il nostro straordinario patrimonio. Cresciuto giornalisticamente dentro Finestre sull'Arte, nel 2025 ha vinto il Premio Margutta54 come miglior giornalista d'arte under 40 in Italia.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.