Cycling in the late1800s was obviously very different from what we know today. Races were held almost exclusively in velodromes, for several reasons. The first: road conditions made it very difficult to organize competitions that took place, precisely, on roads. In addition, organizing races in circuits could allow for better crowd control, as well as the charging of an entrance fee: these were the first attempts to make the sport a profitable activity. Soon, however, cycling began to leave the tracks. The first documented race was in 1868, taking place in Paris and covering a distance of just one kilometer and two hundred meters. Not counting the various more or less improvised endeavors, we have to wait until the following year to see the first “real” race, as we would understand it today: a race between Paris and Rouen, covering a distance of 123 kilometers.

|

| James Moore (right) together with Jean-Eugène-André Castera, respectively first and second place finishers in the 1869 Paris-Rouen race |

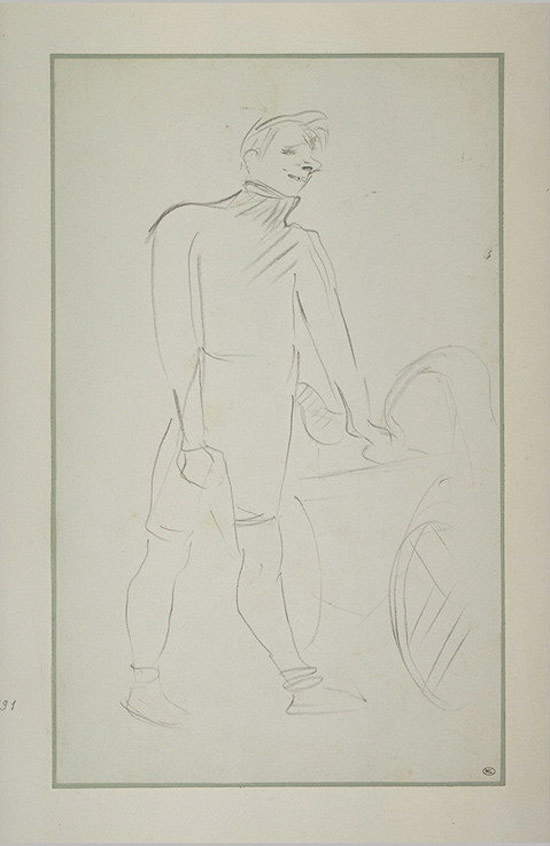

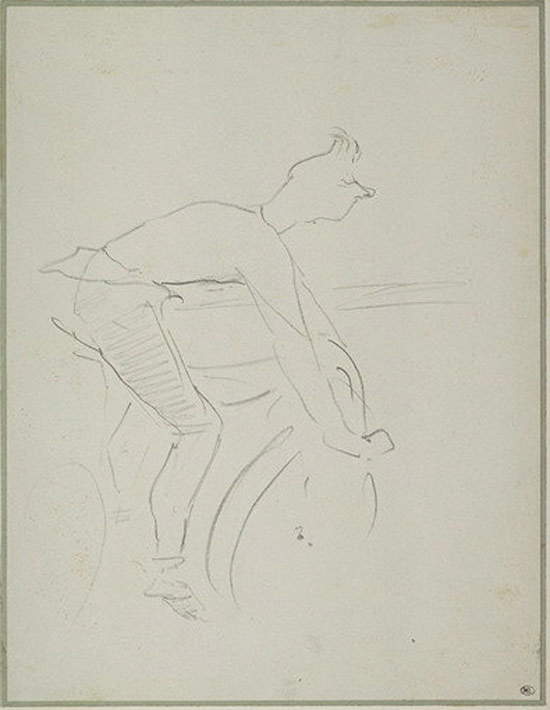

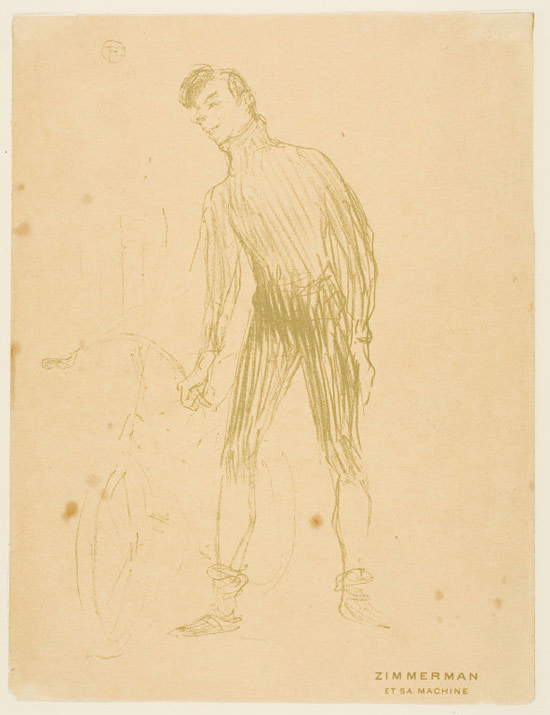

Cycling enthusiasts include, practically from the very beginnings of official bicycle racing, the great artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (Albi, 1864 - Saint-André-du-Bois, 1901): he is an extremely curious man, interested in everything around him. And he is also a more fortunate sports enthusiast than the vast majority of the cycling public: in fact, thanks to his knowledge gained from frequenting the clubs of Paris (Toulouse-Lautrec hates to be alone), the artist can get to know the environment very closely. His acquaintances include the writer and journalist Tristan Bernard, who is a little younger than he is: Bernard and Toulouse-Lautrec know each other because they both collaborate for the Revue Blanche, a cultural magazine founded in 1889. Bernard, before giving himself permanently to the profession of journalist and playwright, engaged in various activities: among other things, he managed a velodrome (the “Buffalo”), and one day he decided to invite the painter to watch the races. The artist thus begins to become passionate: the racing cyclist becomes for Toulouse-Lautrec the emblem of dynamism. A passion that soon spills over into drawings and prints. One of the runners who attracts the artist’s attention is the American Arthur Augustus Zimmerman (1869 - 1936). He is the strongest sprinter in the world, and he is in France to compete in some track races (the chronicles report his victory in the hundred-meter dash at an average of 66 kilometers per hour). Toulouse-Lautrec is attracted by his slender figure and his ability to make the bike run as no one else can: Zimmerman then becomes the protagonist of some preparatory drawings for a print depicting the champion standing triumphant and proud beside his bicycle. Zimmerman proceeds by confidently accompanying the bicycle, or “his machine,” as Toulouse-Lautrec calls it. In the drawings, moreover, the artist depicts him not only standing, as in the finished lithograph, but also running: a few backward strokes make the hair move in the wind, and a few horizontal lines in the background suggest the edges of the track but also give an impression of movement. This is probably one of the very first works depicting a champion cyclist riding his bike.

|

| Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Runner standing beside his bicycle: “Zimmerman and his machine” (1895; drawing, 33.9 x 20.8 cm; Paris, Louvre, Cabinet des dessins) |

|

| Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Runner with his arms stretched out on the handlebars: “Zimmerman” (1895; drawing, 28.6 x 22 cm; Paris, Louvre, Cabinet des dessins) |

|

| Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Zimmerman and His Machine (1895; color lithograph on paper, 22 x 13 cm; various locations) |

Through Bernard’s mediation, Toulouse-Lautrec got to know Louis Bouglé, another great cycling enthusiast (as well as a cyclist himself), who at the time was working as a representative for an English company that manufactured bicycle chains, Simpson. It is a new company, in need of publicity for its product (which is simply called"Simpson chain") and in need of expansion outside the borders of England. This is 1896: Bouglé knows that Toulouse-Lautrec excels at making beautiful advertising posters (the production of which was just then beginning to take the form of anart) and asks him to make a poster to advertise the Simpson chain. The painter accepts, and travels with Bouglé to England to establish the terms of the collaboration. The artist seems enthusiastic about the assignment, and so writes to his mother in 1896: “I accompanied a team of cyclists who went to defend our flag across the Channel. I spent three days with them and returned to France to create a poster for the Simpson chain, which will be a sensational success.” Toulouse-Lautrec, who is a perfectionist, wants to study closely the movements and poses of the cyclists, as well as the structure of a bicycle, in order to create an interesting and, as he hopes, very successful work.

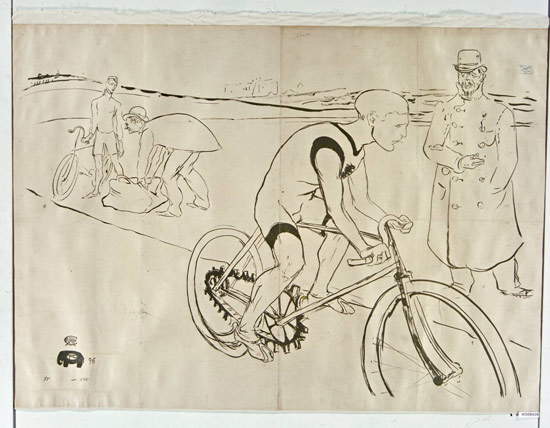

As a “testimonial” for the advertisement, it is decided to depict, on the poster, one of the champions of the time, Welsh professional Jimmy Michael (1877 - 1904), a fresh (as well as the first) winner of the world track middle-distance championship, held in 1895. Toulouse-Lautrec chooses to depict Michael during a training session on the track: next to him, he inserts the figure of sports journalist François-�?tienne Reichel, known as “Frantz,” and further back Michael’s trainer, Englishman James Edward Warburton, known as “Choppy,” caught with another cyclist, arranging a bag. To impart dynamism to the scene, Toulouse-Lautrec decides, as he has been wont to do for some time, to give the scene a photographic slant (the artist is among the first to exploit the potential of photography to update painting): the front wheel of Michael’s bicycle thus remains cut off from the composition, as in a photographic snapshot, to suggest to the viewer the impression of movement. However, the artist chooses to overemphasize the bicycle chain: obviously it is the product that is to be advertised, but the proportions are unnatural, and the stroke is moreover much thicker than anywhere else in the poster. This is a test: the lettering is also missing, the company name is missing, but Bouglé does not like it and therefore rejects the design. Toulouse-Lautrec, however, is not about to throw away his work, and decides to publish it at his own expense: he has two hundred copies printed to get it to cycling enthusiasts. In the printed copies, curiously enough, a monogram in the shape of an elephant appears in the lower left corner of the composition. At this stage of his career, in fact, Toulouse-Lautrec often uses animal figures in which he inserts his initials, “HTL”: this is perhaps a tribute to a painter he admired, James McNeill Whistler, who used to sign himself with the figure of a butterfly.

|

| The Simpson chain, from www.sterba-bike.cz |

|

| Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jimmy Michael (1896; color lithograph, 90 x 127 cm; various locations-above copy held at the Bibliothèque National de France) |

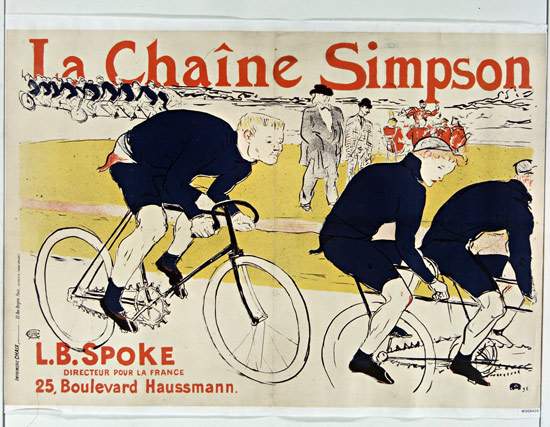

Bouglé’s rejection is motivated by the fact that the chain, according to him, is not drawn well, and moreover, the pedals do not appear in their real position. In short: Toulouse-Lautrec evidently thought he would better highlight the chain by drawing it that way, but the very chain becomes the cause of the rejection. However, Bouglé offers the artist a second chance and asks him to try to come up with a new design. This time, the main protagonist of the poster changes: Jimmy Michael is replaced by a French champion, Constant Huret (1870 - 1951), winner of the first two editions (in 1894 and 1895) of the Bol d’Or, a prestigious international track race that was initially held at the Buffalo Velodrome run by Bernard. The composition becomes much more crowded: Huret is depicted riding his bike, in an aerodynamic position, as he grasps his track crease (the handlebar, in technical jargon), which at the time was finer and less curved than those of today (it must be said, however, that type of shape, the one similar to how we know it today, had been introduced just in the 1890s). The feet push on the pedals and the cheeks puff up to exhale: Toulouse-Lautrec wants to render clearly and eloquently the effort of this strong cyclist portrayed, as previously Michael, during a training session. In front of him are two unidentified tandem cyclists (still partly cut off from the composition, again because of the “photographic” device used in the first drawing), while another group is pedaling in the background on five-seater bikes. Note how the artist decided not to depict (except with a few hints in Huret’s front wheel) the spokes of the bicycles: yet another device to suggest the idea of movement. In the center of the track appear two figures probably identifiable as William Spears Simpson, the owner of the chain company, and Louis Bouglé himself. The drawing is finally accepted: the work can then be translated into print. In the lithograph, Toulouse-Lautrec uses only the primary colors, laid out, as he is now wont to do, in uniform backgrounds, and adds at the top the mark along the entire horizontal line of the scene, and at the bottom the address, name, and nickname of Louis Bouglé, who was known in England as"Spoke," a term that in English identifies the radius of the wheel.

|

| Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, La Chaîne Simpson (1896; color lithograph, 87 x 124 cm; various locations-above copy held at the Bibliothèque National de France) |

However, the success that Toulouse-Lautrec hoped for the campaign would not meet his expectations. Despite Simpson’s huge investment in advertising, the product would soon become obsolete, replaced by more efficient and high-performance models. The company’s life lasted only a few years: as early as 1898 it was put into liquidation. Had it not been for Toulouse-Lautrec’s posters, in all likelihood today the history of this product would have been forgotten, or would have been exclusive subject matter for connoisseurs of cycling history. But the works of this formidable painter are also one of the earliest demonstrations of the spread of the passion for cycling, a sport that had begun to establish itself with the public in those very years, so much so that it was included in the program of the first modern Olympics, those of Athens 1896, with one road trial and five on the track. And they are, of course, evidence of the curiosity of an artist who was able, through his works, to offer a glimpse of the strength, hard work and beauty of one of the world’s most popular sports.

Reference bibliography

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.