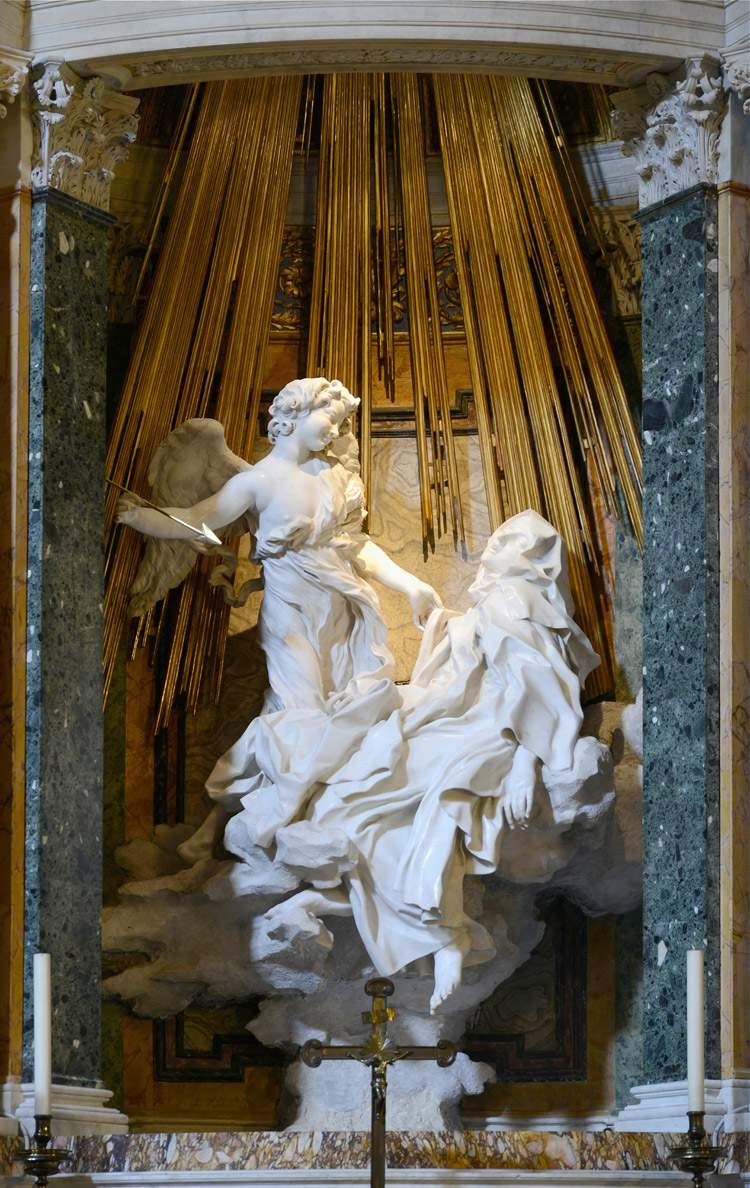

If we had to choose a sculptural group that best represents the seventeenth century and the Baroque, we would most likely point to theEcstasy of St. Teresa by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Naples, 1598 Rome, 1680): it is difficult to think of another work that can compete with Bernini’s group in terms of expressive power, ability to move the viewer and arouse awe and admiration, perfect integration with space, compositional wisdom, and technical mastery. Under a shower of golden light that, in the form of thick rays, descends from above to illuminate the two protagonists, Bernini, in the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome, captures a mystical ecstasy in the midst of its unfolding. St. Teresa of Ávila (Ávila, 1515 Alba de Tormes, 1582), the Spanish nun canonized by Gregory XV in 1622, is losing consciousness and about to fall into a swoon: the expression on her face, caught in the moment of abandonment, leaves no room for doubt. The angel, seraphic, smiling, comes over holding gently a golden dart aimed at the saint’s heart: with his left hand he is already ready to lift her scapular so that he can reach her with his arrow.

|

| Facade of the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome. Photo: Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647-1652; marble and gilded bronze, h. 350 cm; Rome, Santa Maria della Vittoria). Credit |

We are dealing with a work intended to offer a faithful depiction of a passage from the autobiography of Teresa of Ávila, which the saint composed between 1562 and 1565. Thus we read in the description of the ecstasy: “Veía un ángel cabe mí hacia el lado izquierdo en forma corporal, lo que no suelo ver sino per maravilla. [...] No era grande, sino pequeño, hermoso mucho, el rostro tan encendido que parecía de los ángeles muy subidos, que parecen todos se abrasan. [...] Veíale en las manos un dardo de oro largo, y al fin de hierro me parecía tener un poco de fuego. �?ste me parecía meter por el corazón algunas veces, y que me llegaba a las entreñas. Al sacarle, me parecía las llevaba consigo, y me dejaba toda abrasada en amor grande de Dios. Era tan grande el dolor, que me hacía dar aquellos quejidos; y tan excesiva la suavidad que me pone este grandíssimo dolor, que no hay desear que se quite, ni se contenta el alma con menos que Dios. No es dolor corporal, sino espiritual, aunque no deja de participar el cuerpo algo, y aun harto. Es un requiebro tan suave que pasa entre el alma y Dios, que suplico yo a su bondad lo dé a gustar a quien pensare que miento” (“I saw an angel near me, to the left, in carnal likeness, such as I had never seen except in my visions. [...] He was not tall, he was small, and very beautiful, his face was so lit up that he looked to me like one of the angels of the highest hosts, the ones who seem to burn. [...] I could see in his hand a long golden dart, and at the end of the iron there seemed to me to be some fire. It seemed to me that with the dart he would pierce my heart a few times, and it would go all the way to my bowels. When he took the dart out, it almost seemed to me that he took them away with him, and left me all burning with a great love for God. The pain was so great that it made me utter a few moans, but so great was the sweetness that this very strong pain gave me, that I could not wish for it to stop, nor for my soul to be content with anything other than God. It was not a physical pain, but a spiritual one, although to some extent the body itself was a part of it, indeed it was very much so. It was such a sweet caress between the soul and God, that I pray to His goodness that even those who think I lie may experience it.”

It is entirely safe to assume that Teresa of Ávila’s autobiography was the first source from which Bernini drew for his own image: one would not otherwise explain the sculpture’s such close adherence to the text, with which the artist was able to familiarize himself perhaps also thanks to the excerpts contained in the 1622 bull of canonization. Indeed, Bernini takes care to give shape to every single detail of the saint’s narrative: the angel arriving from the left, small and handsome. The long golden dart pointed toward the heart. St. Teresa’s face contracted into a grimace of pain. The open mouth groaning. The sensation of pain shaking her body. The flames, which once enveloped the arrow (the one we see today is a later replacement). Finally, there are also those to whom the saint addresses her message. And we are not just talking about us who observe and are called to be active participants in such a vision: at the sides of the main scene, as if we were in a theater, we notice in fact two foreshortened boxes in perspective, from which some characters look out in curiosity and wonder. They are members of the Cornaro family (or Corner, in the Venetian way: they were in fact from Venice), from which came the commissioner of the sculptural group, Cardinal Federico Cornaro, who, having obtained in 1647, on January 22, the juspatronage of the chapel of the left transept of Santa Maria della Vittoria, wished to make it his own burial place. However, it is entirely probable that the contacts between patron and artist dated back to months before that date, not least because at the beginning of 1647 the work was already in progress, and because there are other cases, in the same building of worship, of title to a chapel being granted while work was already in progress. It would take five years to complete: 1652 is the year in which Bernini finished waiting on his masterpiece.

|

| The Cornaro chapel in Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome. Credit |

|

| The altar with the Ecstasy of Saint Theresa. Photo: Finestre Sull’Arte |

Federico Cornaro’s idea was, all things considered, rather simple: his intention was in fact to celebrate the family, which until then numbered seven cardinals, including Federico himself, and one doge (Giovanni I Cornaro, supreme authority of the Venetian Republic from 1625 to 1629, as well as Federico’s father), while at the same time honoring the most important saint of the Carmelite order, the same for which the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria was built. The eight Cornaros are all portrayed in the boxes on either side of the main group: on the right, we find Francesco senior, Federico (he is the second), Andrea and Luigi, while on the left we observeFederico senior, Francesco iunior, Marco (the youngest) and Doge Giovanni I. All the figures face the balustrades of the boxes: behind them are splendid stucco architectures rendered in perspective.

Bernini obviously does not limit himself to a simple family portrait. For him, everything is functional in capturing the observer (but it would not be daring to use the term “spectator” as well), and consequently the portraits of the Cornaro family also participate in the grand theatrical scenography he devised for the Cornaro Chapel (it is no coincidence that many art historians have spoken of theatrum sacrum, “sacred theater”): architecture, sculpture and painting come together to guide the observer to contemplate the vision before him, but also to lead him to reflect on the mystery of Saint Theresa’s ecstasy. The viewer remains involved, yes, but a certain distance separates him from the sacred scene, plus the Cornaro’s astonished, surprised and sometimes bewildered expressions are clearly meant to emphasize the impossibility, on the part of the human mind, of scrutinizing the designs of divinity. It is necessary, however, to point out the differences between the two boxes, which have suggested the extensive use of workshop aids. The group on the right, carved from a single block of marble and showing different manners than the one on the left (the portrait of Federico, the only one not executed posthumously, appears to us more vividly than the others, and probably the master himself took care of it) is to be assigned to Bernini, with probable help from Jacopo Antonio Fancelli (Rome, 1606 - 1674), brother of the better-known Cosimo. The group on the left, less vigorous and instead more delicate, denotes the participation of a different and independent artist, capable of “already giving a personal interpretation of Bernini, pictorial, vibrant and sentimental” (so Livia Carloni): this would be Antonio Raggi (Vico Morcote, 1624 Rome, 1686), a Swiss sculptor from the Canton Ticino to whom some payments traceable to the Cornaro Chapel enterprise are documented.

|

| The left antependium in the context of the Cornaro chapel. Photo: Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The left antependium. Credit |

|

| The right palchetto in the context of the Cornaro chapel. Photo: Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The right palchetto. Credit |

As mentioned, the figures in the boxes lead us to the centerpiece of this sacred theater: the group representing the transverberation of St. Theresa, that is, the vision of the angel piercing the saint’s heart with an arrow(transverberare, in Latin, means precisely “to pierce”). Every detail is studied by Bernini in great detail: thearchitecture itself can be considered an integral part of the work. To “frame” the sculptural group, the artist designs a niche with a curvilinear, convex course, framed by two pairs of columns and surmounted by a tympanum that is also curvilinear: an expedient to bring the work closer to the observer and to increase the theatricality of the whole. Completing thatunity of the arts to which Baroque art often tended and which also often connoted Bernini’s machinations, are the painted stucco clouds that decorate the ceiling of the Cornaro Chapel and were made by Guido Ubaldo Abbatini (Città di Castello, c. 1600 Rome, 1656), who was also a collaborator at the time in other Bernini endeavors. Abbatini’s clouds invade the entire upper space of the chapel, going so far as to overflow beyond the limits imposed by the archway: in doing so, the Umbrian fresco painter not only panders to Bernini’s desire to create a unique space in which, as mentioned earlier, architecture, sculpture and painting unite and mingle, but also anticipates what will be a typical trait of the great Baroque decoration and which will spread a few decades later. From the clouds appear angelic hosts intent on observing the event, and above all, in the middle of such a blanket, we can observe the dove of the Holy Spirit, the true metaphysical source that justifies the divine light that floods the scene.

Indeed, it should be pointed out that, in Bernini’s great theater, a prominent role is played by light. And we are not just talking about the gilded bronze rays that Bernini inserts behind the figures of the angel and St. Theresa flooding the niche with the divine presence that makes the miraculous ecstasy possible: considerable is the importance of natural light. To procure an inexhaustible source of it, Bernini wanted to open a window, at the height of the tympanum: the natural light in this way rains down from above, illuminating the golden rays, with which the light from the window blends, and bringing out the folds of Saint Theresa’s robe shaken by the vision, the angel’s smile well marked by the contrasts between the light and the penumbra, the movement of the arms of the divine creature about to strike the saint’s heart with her dart, the quivering of her who, in a mixture of joy and sorrow, surrenders herself to that “great sweetness” she had so ardently described in her autobiography. It is a light in which, as one of Bernini’s leading experts, Marcello Fagiolo, wrote, “the figures of Teresa and the Angel truly appeared as a supernatural, phantasmal vision, floating mysteriously in the void.” The mystery to which the scholar alludes is that of transverberation: so great as to move to amazement the very members of the Cornaro family who witness the event, so distant from us that Bernini was forced to make certain solutions in order to make the observer understand that he was facing an event to which it is impossible to give a rational explanation.

|

| The vault with paintings by Guido Ubaldo Abbatini. Photo: Steven Zucker |

|

| The window as seen from the outside. Photo: Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The face of St. Teresa. Credit |

|

| The folds of the robe and the hand. Credit |

|

| The cloud and the foot of the saint. Credit |

|

| The angel. Credit |

The “floating” mentioned by the scholar is one such solution. The marble bodies, a heavy material par excellence, appear to us to be exceedingly light in their movement in mid-air (the group, moreover, does not rest on the ground, but is attached to the chapel wall from behind, to give the illusion that the figures really hover in space), suspended on those little clouds that transport Saint Teresa into a spiritual dimension. And again, the air that lifts her robe, moving it in all directions and causing it to take on unnatural folds, seems almost to nullify her bodily nature: under the thousands of folds of the ample habit, we cannot distinguish Saint Teresa’s features, and to our sight only her delicate feet, beautiful hands and face crossed by this unspeakable feeling present themselves. And yet, despite this absence of corporality, certain authors have tried to provide an interpretation of St. Theresa’s ecstasy in an erotic key: an interpretation that is certainly suggestive and comforted by the subtle sensuality that the work can certainly inspire, but which nonetheless ill suits the sources that speak of Bernini as a very religious artist and who, therefore, we can imagine little inclined to provide representations of the saint that he might have considered blasphemous.

If we happened to read Bernini’s biography written by his son Domenico, we would make the acquaintance of an artist accustomed to reciting the rosary, listening to Mass every morning, reading the psalms, and devoting himself to many other practices typical of the religiosity of the time. Bernini’s devotion is confirmed by, among others, Paul Fréart de Chantelou, the French collector appointed by Louis XIV to receive Bernini during his stay in Paris in 1665, who noted in his diary every time Bernini asked him to accompany him to Mass, and by Filippo Baldinucci, who informs us how the artist took communion twice a week and how he kept “a lively thought of death, around which he did well often long conversations with Father Marchesi his nephew priest of the Congregation of the Oratory in the Chiesa Nuova.” Despite such portrayals, there have been authors, mainly from psychoanalysis, who have tried to read Saint Theresa’s ecstasy in more “earthly” terms. Jacques Lacan, for example, spoke of St. Theresa in this way, “Vous n’avez qu’aller regarder à Rome la statue du Bernin pour comprendre tout de suite qu’elle jouit, ça ne fais pas doute” (“All you have to do is go to Rome and look at Bernini’s statue to understand at once that she is enjoying, there is no doubt about it.”) The verb jouir used by Lacan (and which relates to his concept of jouissance, which is very difficult to define), has been interpreted by many in an erotic key, as if the saint is experiencing an orgasm. These would not, however, be forced visions: a certain sensual charge was felt even by Bernini’s contemporaries. An anonymous (and rather venomous) commentator, a contemporary of Bernini, wrote, in reference to St. Theresa, that the artist “pulled that most pure Virgin on earth, not that in the third heaven, to make a Venus not only prostrate, but prostitute.” Stendhal, in his Promenades dans Rome, reports that the friar who accompanied him and his friends on their visit to Santa Maria della Vittoria confided to him that"it is a great pity [sic] que ces statues puissent présenter facilement l’idée d’un amour profane“ (”it is a great pity that these statues can easily inspire the idea of a profane love").

However, without going into even a partial disanimate of those who have tried to give a carnal connotation to Bernini’s group, scholars opposed to such a view have argued about the expression assumed by the face of St. Theresa (which remains, however, undoubtedly similar to that of any woman caught in full erotic ecstasy) arguing that Bernini would have done nothing more than stick to his main literary source: the saint’s autobiography. Recently, however, a specialist scholar of the Baroque, Saverio Sturm, has wanted to add at least a couple of other possible sources that, alongside the description cited at the opening of this article, may have inspired Bernini’s image: one is the Llama de amor viva by John of the Cross, a Spanish Carmelite mystic who used the figure of the flame to symbolize the soul’s encounter with God (“Oh, llama de amor viva, / que tiernamente hieres / de mi alma en el más profundo centro! / Pues ya no eres esquiva, / acaba ya, si quieres, / rompe la tela deste dulce encuentro,” “O, flame of living love, / that tenderly wound / of my soul the deepest center! / Since you are not shy, / end now, if you will, / break the veil of this sweet encounter”). The other source could be the Loda a santa Teresa by poet Antonio Bruni, who included the long lyric in a collection, Le Veneri, published in 1633 and dedicated to Odoardo I Farnese, duke of Parma and Piacenza. In the poem we can read an extensive narrative of the encounter between St. Teresa and the angel, of which we quote the verses describing the moment when the angel pierces the saint with the dart: “Qui de la pungentissima saetta / de’ mortali invisibile a la luce; / nel grembo virginale il colpo affretta, / de’ bei colpi d’Amor maestro e duce. / But, if ’blade of her the angel thrusts, / She draws no blood from it, and ’in her splendor adduces: / But, if the heart with golden arrow impairs her, / Her medica is the wound, the pain relief. / La vergine ferita il cor ben sente / Stemprato in gioia, e liquefatto in sangue; / ma con tenderi gemiti languente / mostra piagato il sen, la piaga essangue. / Estasi amorosissima la mente / l’innebria, e sol d’Amor sospira, e langue / Ma i suoi dolci languori hanno la palma / D’accrescer luce al seno, e piaga a l’alma.”

That great love of which the poet speaks is the same love that God declares to the saint by means of the scroll carried by the two angels at the top of the chapel. Nisi coelum creassem, ob te solam crearem, or “if I had not created heaven, I would create it only for you”: truly strong words, denoting a boundless love that transcends any dimension, and reinforcing the message of one of the most celebrated, wonderful and intense sculptures in all of art history. And to think that Gian Lorenzo Bernini, at the height of his typical modesty, used to say that Saint Theresa was “the least bad work” he had made.

Reference bibliography

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.