It is one of the most photographed works by Edgar Degas (Paris, 1834 - 1917) in the world. In fact, there are twenty-six examples of the Petite danseuse of fourteen years old , the most famous ones kept at the Musée d’Orsay, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, but only one can be considered to be the original, made directly by the artist. The first example of Petite danseuse was in fact made in wax and is the one now in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, while all the others are bronze versions of the original. It is also the only sculpture that Degas exhibited publicly during his lifetime, specifically at the sixth Exposition des Indépendants in 1881.

It should be noted, however, that while today the sculpture is so appreciated in every version by visitors to all museum venues that hold a specimen, when the statue was first unveiled it did not receive this treatment, quite the contrary. Critic Henry Trianon was outraged at the ugliness of that sculpture and made bad irony by stating that “in the slums of the dancing schools, there are poor little girls who resemble this little monster”; he further suggested that “they should be put in a museum of zoology, of anthropology, of physiology, but not in a museum of art.” And not content, he added again that Degas had chosen it from the most “hideously ugly.” Élie de Mont commented, “I don’t ask that art always be elegant, but I don’t think its role is to support the cause of ugliness,” and likened Little Ballerina to “an ape, an Aztec, to be put in a container under formalin,” while Paul Mantz said: “The bourgeois admit that they are astonished to contemplate this wax creature, but one hears fathers praying to God that their daughters will not become ballerinas,” and spoke of the “instructive ugliness of the face,” reasoning that “no doubt Degas is a moralist.” Degas’s attitude was in his opinion one of “bestial effrontery.”

|

| Edgar Degas, Little Dancer of Fourteen (1878-81; colored wax, metal, human hair, silk and linen ribbon, lace bodice, cotton and silk tutu, silk slippers, on wooden base, 98.9 x 34.7 x 35.2 cm without base; Washington, National Gallery of Art, Paul Mellon Collection) |

|

| Edgar Degas, Adrien-Aurélien Hébrard, Little Dancer of Fourteen (1921-31; patinated bronze, tulle tutu, satin ribbon, wooden base, 98 x 35.2 x 24.5 cm without base; Paris, Musée d’Orsay). Credit Musée d’Orsay |

|

| Edgar Degas, Adrien-Aurélien Hébrard, Little Ballerina of Fourteen (1922; bronze, tarlatan, silk satin, wood, 97.8 x 43.8 x 36.5 cm; New York, Metropolitan Museum) |

The Little Dancer caused such a stir because it was something very innovative from the point of view of sculpture at the time: it totally broke out of the mold of marble statues that often depicted idealized nudes in the usual displays. Thedeparture from traditional classical French sculpture was embodied in this work in the use of unconventional and realistic materials and in the pose that did not at all hint at grace, elegance and beauty, attributes usually associated with the world of dance. The statue was modeled in colored wax (not traditional marble), and also featured real accessories: she had real human hair tied with a satin ribbon, wore a cloth bodice, a lace tutu, and pink silk ballet slippers. The pose was far from the upright and composed posture typical of a ballet dancer, as her chest and chin stretched forward in an ungainly gait, her hands were clasped behind her back, her right leg placed forward with her foot in en dehors, yet assuming a relaxed posture. For this reason, critics had perceived in Degas’ sculpture the ugliness of the dancer, for it was a complete departure from the graceful and refined models of ballerinas they were accustomed to admiring in these exhibition settings. Also adding to the feeling of being in front of an ape, as had been claimed, or at any rate a creature to be studied zoologically or anthropologically, was the fact that the statue was enclosed in a glass case, like an artifact in an ethnographic museum. Degas’ sculptural representation of arat, an appellation by which the young dancers of the Paris Opera are still referred to today, was thus extremely far removed from the academic tradition and the milieu of the French bourgeoisie. The rats at the time usually came from working-class families, which according to the ideas of the time were believed to be much more vulnerable to moral corruption. Degas probably wanted to give his Little Dancer the appearance of a young woman, about to become a woman, belonging to that social context, and he did so by distorting her physiognomy.

Disagreeing with the critics mentioned above was the literary scholar and critic Joris-Karl Huysmans, who was positively amazed by Degas’ Ballerina. He called it “the only three-dimensional work in the exhibition,” the “first formulation of a new art.” Because of the materials used and the technique of making it, he likened it to “the method of the old Spanish masters,” finding a resemblance to the “Christ of Burgos Cathedral, whose hair is real hair, whose thorns are real thorns, whose fabrics are real cloth.” He further declared, “refined and barbaric at the same time, with its ingenious dress and colorful flesh throbbing, furrowed by the workings of muscles, this statuette is the only attempt at true modernization of sculpture that I know of.” “The terrible reality of this statuette caused the public obvious discomfort,” Huymans added, "all their ideas about sculpture, about these cold inanimate whites, about these famous stereotypes copied for centuries, are upset. The fact is that with his first attempt Monsieur Degas revolutionized the traditions of sculpture as he had long since shaken the conventions of painting." Degas was probably inspired by the wax statues of Madame Tussauds in London, the wax mannequins of Parisian ethnographic exhibitions.

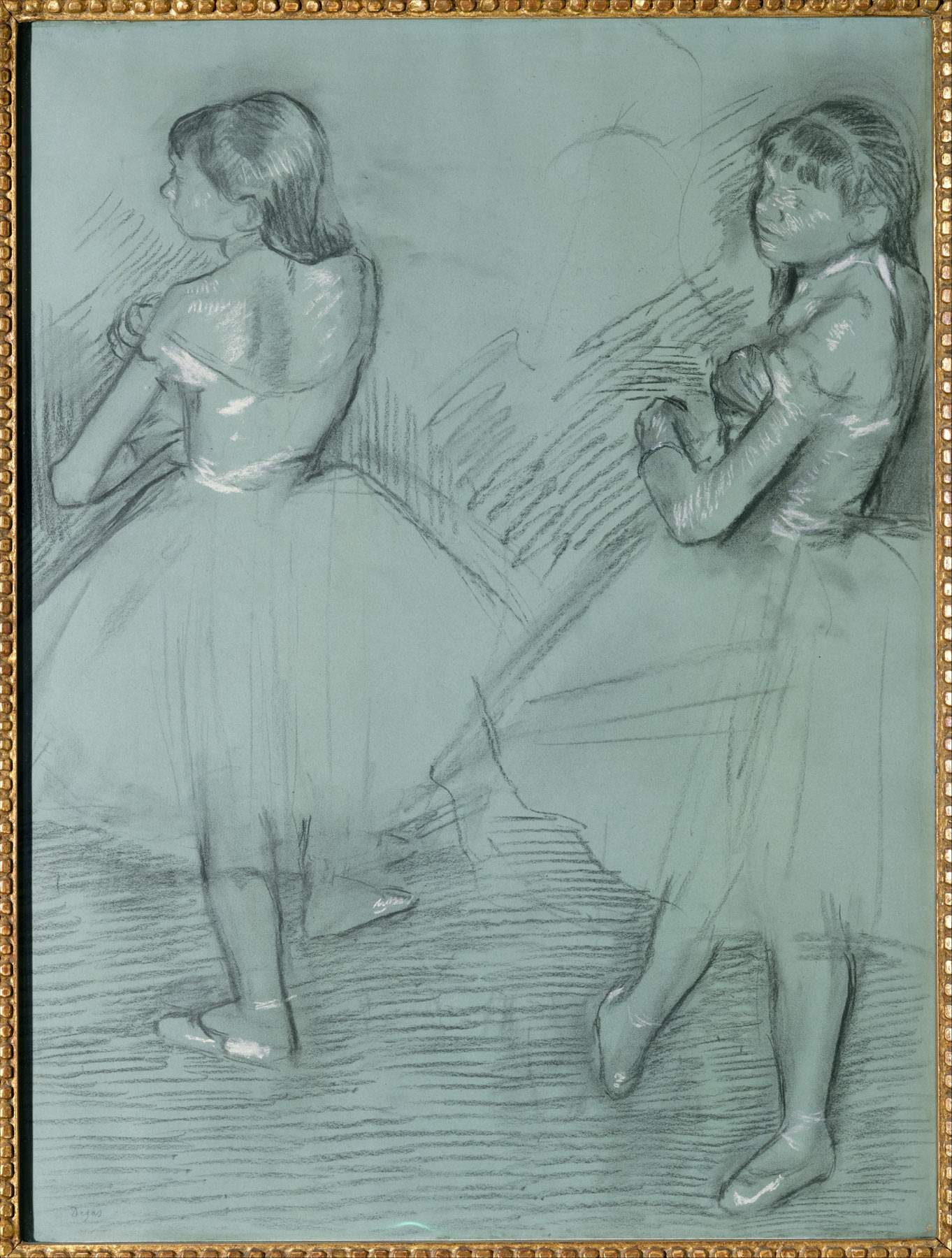

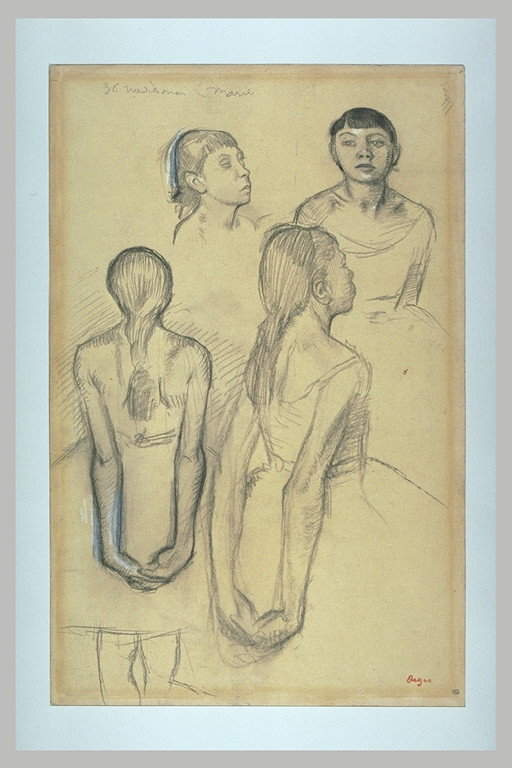

Before making the sculpture, the artist made some studies on paper, drawing the dancer from different angles. These drawings are divided mainly into groups: some show the young dancer clothed or nude from five different angles in a pose similar to that of the final sculpture, although her arms are placed in front of her chest, and where clothed, she is adjusting her epaulet. Others still depict her nude or clothed in the same pose as the sculpture, while additional drawings are devoted to her head, torso, and arms, and even one entire sheet contains five studies of just her feet. The Louvre’s Cabinet of Drawings holds a sheet with four studies of a ballerina bearing a name and address, the same ones that appear in a notebook that Degas used between 1880 and 1884: the details refer to a certain Marie van Goethem, the young woman who modeled for the fourteen-year-old Little Ballerina. In fact, Marie, born on February 17, 1864, was exactly fourteen years old in 1878. The four studî depict the dancer in the pose adopted in the statue. Perhaps the presence of the name and address on that sheet indicates the latter as the first in a series of studies of Marie in that pose and with the tutu. A sheet preserved instead at theArt Institute of Chicago depicts three studies of the dancer in fourth position, one frontal and the others in the two profiles; the pose is still the one that will be adopted in the sculpture. The Chicago drawing is one of the finest of this group and is related to another sheet of the same size, belonging, however, to a private collection, which depicts Marie in three back studies. Belonging to the collections of the Metropolitan Museum in New York is the sheet entitled Two Ballerinas: in this case, the dancers do not have their arms behind their backs, but are adjusting the shoulder straps of their dresses.

|

| Edgar Degas, Two Ballerinas (ca. 1879; charcoal and white chalk on coated paper, 63.8 x 48.9 cm; New York, Metropolitan Museum) |

|

| Edgar Degas, Three studiesî of a dancer in fourth position (1879-80; charcoal and pastel on paper, 48 x 61.6 cm; Chicago, Art Institute) |

|

| Edgar Degas, Four studies of a ballerina (RF 4646, Recto; Paris, Département des arts graphiques, Fonds des dessins et miniatures, collection du musée d’Orsay) © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) - Photo Adrien Didierjean |

Of the young Marie van Goethem , the sad story is known in broad strokes: as a child, Marie dreamed of becoming a ballerina at theParis Opera. For her, dance represented a kind of escape, as well as a source of joy, to combat the poor living conditions in which her family found itself: she was the daughter of a tailor and a washerwoman, but her mother had fallen into alcohol and prostitution, and she lived in the Notre-Dame de Lorette neighborhood, an area known since the nineteenth century for severe social degradation. Marie was admitted to the prestigious ballet school, where she met Degas, who, as is evidenced by the numerous pictorial depictions of the world of dance and the stage, was endlessly passionate about it.

However, after being portrayed several times in drawing and sculpture by the famous artist, the young woman increasingly abandoned dance; she began to frequent taverns and unsavory places, eventually falling into vice and prostitution. It is said that the situation worsened further when her father died, as her mother was forced to prostitute her three daughters in order to survive. Because of this Marie was no longer admitted to classes, partly because of too many absences: thus ended her dream of being a dancer. From that time on, there are no more records of Marie. Her name disappeared from the records of the Paris Opera; one of the sisters was arrested for theft, and Marie herself also suffered arrest for attempting to pickpocket one of her clients.

The story of a shattered dream lives on in all the examples of Little Dancer as a fourteen-year-old, from the original one in the National Gallery of Art in Washington to bronze ones in the world’s most prestigious museums. The only sculpture Degas decided to exhibit in his lifetime: when he died in 1917, his workshop revealed a treasure trove of as many as 150 hitherto unknown wax or earth sculptures.

Essential bibliography

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.